The tractor allows and empowers my personal participation in the rhythms of the natural world. I can plant and pick, harrow and harvest generous crops in season. To me, my tractor seems a heroic thing.

But in the field of farm tractors, my Deere is as small as they run. Even if you’re not a farmer, you’ve seen tractors twice and thrice the power of mine commonly plowing the dark Midwestern soil. And on the larger tracts, you’ve seen modern behemoths cut swaths as wide as avenues through dustier fields, wearing double tires on every wheel, pulling several gangs of plows and harrows, while the operator sits bunkered in an air-conditioned cab, watching the tracks of his tires in a television monitor.

Me, I take the weather on my head. I mow at a width of six feet. And mine is but a two-bottom plow.

Nevertheless, as small as my tractor is, smaller still was the first tractor purchased by my father-in-law, Martin Bohlmann, in the late 1940s when his daughter Ruthanne was six years old.

A sad elemental yearning

When I was a young man, I once sat down to supper with the farmer and his family in their spacious kitchen. Outside, the evening air was warm, rich and loamy. Jonquils and daffodils were in bloom, the tulip buds about to pop. It was nearly Easter. I had come to court Ruthanne, the farmer’s daughter.There were eight of us at the table, though it could accommodate 15 at least. Martin and Gertrude had borne 14 children. They buried one in infancy and now had watched nearly all the others leave for college.

The farmer bowed his head. We prayed and began to eat. Potatoes and vegetables had been raised in the kitchen garden. Popcorn, too. Milk came from their own cows. There had been a time when the hog had been hung up on a chilly autumn morning and butchered in the barn door to become cracklings, hams, chops, sausages, lard. The Bohlmanns didn’t own the land they worked or the house they slept in. They rented. They never paid income tax, since their annual income never approached a taxable figure. For them it was a short distance from the earth to their stomachs and back to earth again. “Thanne” remembers when they had no plumbing.

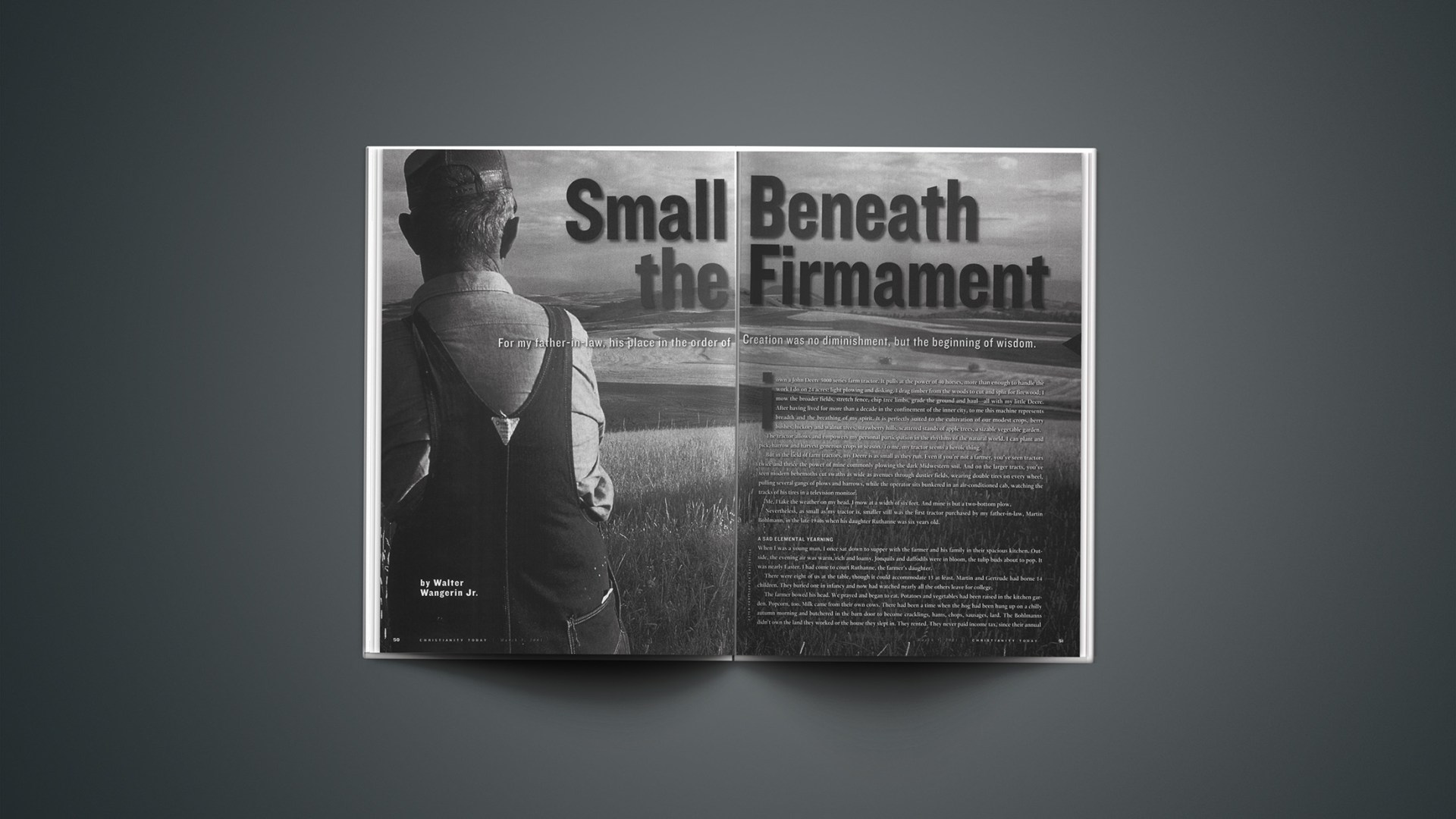

We consumed our supper mostly in silence. Then, at the end of the meal, Martin put a toothpick in the corner of his mouth, read a brief devotion, pushed back his chair, stood up, and walked outside. I followed as far as the porch. In twilight the farmer, clad in clean coveralls, strolled westward into the field immediately beyond the house. He paused. He stood in silhouette, the deep green sky framing his body with such precision that I could see the toothpick twiddling in his lips. His hair was as stiff and wild as a thicket, his nose majestic.

Slowly, Martin knelt down on one knee. He gathered some soil in his right hand and squeezed and sifted the dirt through his fingers to the palm of his left. Suddenly he brought both hands to his face and sniffed. He switched the toothpick. He touched the tip of his tongue to the earth. Then he rose again, softly clapping his two hands clean and slipping them behind the bib of the coveralls. He stood there, Martin Bohlmann, gazing across the field, black as iron in the gloaming, his elbows forming the joints of folded wings—and I thought, How peaceful! How completely peaceful is this man.

It caused in me a sort of sadness, a nameless elemental yearning.

Buying a sturdy servant

Martin purchased that first tractor of his—a John Deere exactly as green as mine but smaller and less powerful—at the only price he could afford, something less than $200. Billig, he judged the sale, German for “cheap,” which in his mouth meant “Such a deal!” He bought the tractor used from one of his neighbors. The machine wasn’t even two years old but it had kept stalling. In the barnyard, in the field, it would quit, then refuse to produce a spark for starting again, however hard the poor man cranked it. The neighbor figured he was selling aggravation.Martin, on the other hand, was buying a sturdy servant, not only with cash but also with his character: less than $200 bought the cold equipment; patience and peace bought time to examine it with a complete attention, his mind untroubled, undivided; and mother-wit brought the tractor to life again.

In those days tractors used a magneto generator. My father-in-law opened it and discovered a loose washer inside. The washer had shifted whenever the tractor bumped over rough ground, shorting the coils and killing the engine. Martin simply removed that washer. Thereafter he had a dependable tractor for as long as ever he farmed. It was there when I came courting Ruthanne. It was there when he finally retired at the age of 70 and was forced to auction off his farming equipment.

Quiet obedience

My father-in-law was born in the early 20th century. His relationship to the earth, therefore, was established long before society developed its ever more complex technologies for separating human creatures from the rest of creation.Throughout his young manhood, farming was the labor of muscle and bone, hoof and hand. The very first successful gasoline tractor wasn’t produced until 1892. In 1907 there were a mere 600 tractors in the whole of the United States.

Thanne still remembers the years before her father purchased that first John Deere, when he plowed behind draft horses, Prince and Silver, steady beasts with hooves the size of a little girl’s head. Often she was sent to lead them to water. And this is why she remembers the time and the chore so well: it frightened the child to walk between two massive motors of rolling hide, her head below their necks. The quicker she went, the quicker they took their longer paces, until she thought she could never stop them, and they all would fly into the pond.

Her father, however, commanded them mutely with a gesture, a cluck, a tap of the bridle. Silent farmer. Silent, stolid horses. They were for him a living, companionable power. When they spent days plowing fields together, their wordless communication became community. The farmer never worked alone. He was never isolated. And if the dog ran beside them, then there were four who shared a certain peace beneath the sky, four who could read and obey the rhythms of creation, four creatures, therefore, who dwelt in communion with the Creator.

Horses plowed. Horses mowed. Horses pulled the rake that laid the alfalfa in windrows to dry—giving Martin’s fields the long, strong lines of a darker green that looked like emotion in an ancient face.

And when the hay was dry, horses pulled a flat wagon slowly by the windrows while one man forked the hay up to another who stood on the wagon. That second man caught the bundles neatly with his own fork and flicked them into an intricate cross-arrangement on the wagon, building the hay tighter and higher, climbing his work as he did, climbing so high that when the horses pulled the wagon to the barn, the man on his haystack could stare dead-level into the second-story windows of the farmhouse. Then horses pulled the rope that, over a metal wheel, hoisted the hay to the loft in the barn.

Martin and his neighbors made hayricks of the overflow. They thatched the tops against rain and the snow to come. The work caused a gritty dust, and the dust caused a fearful itch on a summer’s day. But the work and the hay—fodder for fall and the winter to come—were a faithful obedience to the seasons and the beasts, Adam and Eve responsible for Eden. Martin Bohlmann knew that.

He milked the cows before sunrise. There was a time when he sat on a stool with his cheek against their warm flanks in winter. Cows would swing their heads around to gaze at him. He pinched the teats in the joint of his thumb and squeezed with the rest of his hand, shooting a needle spritz into the pail between his feet. He rose. He lifted the full pail and sloshed its blue milk into the can; then he carried the cans, two by two, outside.

The winter air had a bite. His boots squeaked on stiff snow as he lugged the cans to the milk house. The dawn was gray at the eastern horizon, the white earth ghostly, the cold air making clouds at the farmer’s nostrils—and someone might say that he, alone in his barnyard, was lonely. He wasn’t, of course: he was neither lonely nor alone. His boots still steamed with the scent of manure; his cheek kept the oil of the cattle’s flank; the milk and the morning were holy. They were manifestations of the Creator—and the work was Martin’s peaceful obedience.

Ask what the water wants

Near the western boundary of my acreage, the land descends to a low draw through which my neighbor’s fields drain their runoff water. When we first moved here, the only way I could get back to the woods and my writing studio was through that draw. But every spring the thaw and the rain turned it into a stretch of sucking mud.In order to correct my problem, I laid a culvert east-and-west over the lowest section, then hired a man with a diesel earth shovel to dig a pond on the east side of the draw and pile that dirt over my culvert. I built a high bank, a dry pathway wide enough to take the weight of my tractor. I seeded it with grass, and the grass grew rich and green. Had God given us dominion over the earth? Well, I congratulated myself for having dominated this little bit of earth—until the following spring, when severe storms caused such thundering floods that the earth broke and my metal culvert was washed backward into the pond.

I tried again. I paid several students from the university to help me reset the culvert, redig and repile the earth upon it. I walled the mouth of the culvert with rock and stone in order to teach the water where to go. I reseeded the whole, and during the summer months I watched … as little runnels found their little ways under the culvert. By spring the runnels had scoured out caves, and the caves caused the culvert to slump, so that by autumn my draw had returned to its primeval state: mud.

When was it my father-in-law came to visit? I showed him my tractor. I showed him my fields. I asked him, as always, interminable questions, which he answered, as always, with two words and peace. My foolishness and all my concomitant anxieties were swallowed up—always, always—in the infinitude of Martin’s patience. I showed him my failed culvert.

He said, “Take your time. You’ve got time. Ask the water what she wants, then give her a new way to do it.”

Go to the farmer

When it idles, my John Deere 5000 makes a low muttering sound. At full throttle it produces a commanding growl. But its voice is muffled, modern.Martin’s first tractor uttered that steady pop-pop-pop-pop which, when it crossed fields to the farmhouse, revealed the essential vastness of the earth and all skies.

Pop-pop-pop-pop! Look. Follow the sound with your eyes. See him moving slowly between solitary cottonwoods: one man on a tractor far away, creeping the low land under the white cumulus giants that people the blue sky. Look again and see yourself, for this is our true size upon the circle of the earth, as Isaiah declares: Its inhabitants are like grasshoppers.

Does such diminishment crush you? Does it oppress or depress you, O Lofty Soul, to be reduced to a plant-eating insect? Are you rather more inclined to take power over your environment, heating it and cooling it according to your physical comfort, as if you were the standard of the weather? Encountering the world through car windows and television screens, O Citizen of the First World, thou art seldom wet, seldom sunstruck, never in darkness if you don’t wish it, never a soul in communion with the soil, scarcely aware of the daily rhythms of creation, ever an alien on the earth, one who is alerted to her presence only when she turns around and dominates our pitiful dominion over her: hurricanes, tornadoes, blizzards, “acts,” we say, “of God.” Are you any less anxious for all your technologies of speed and swift communication with anyone but creation? Surely patience is not the virtue of e-mailing and cell-phoning. But are you more peaceful for all the distance now established between the earth and your stomach?

If Isaiah’s description of your puling importance offends you, go out and garden. Plant things. Cultivate them. Pick them and eat them. Be forced to watch the weather. Try dependence on the creations of God at least as much as you depend on the inventions of humankind. Which would you rather obey? Which is it that loves you, even to the end?

Go, I suggest, to the farmer.

And if you cannot farm like him, watch him. Learn of him. Take your children to the places where people depend upon the earth: depend directly upon the earth, its produce, its benevolence, its living resource. Work with the farmer. Talk with him. Purchase some necessary food, whether fruit from the orchard, vegetables from the garden, eggs from the coop, or flowers. And find the farmer, if not in your own family, then through the networkings of your church or your denomination.

But I tell you from my own experience: even in the inner city, there are vacant lots waiting with eager longing for the clearing and the tilling of the children of God.

Reading the weather obediently

How peaceful! How completely peaceful was the man!Once that observation filled me with a melancholy longing, since what Martin was, I was not. But that was more than 33 years ago.

In the meantime, I have come to know the man because I have been his son-in-law; and I have come to know his peace because I went out and joined myself to the rhythms of creation. However foolish and light my effort, I have a tractor. I do a little farming.

Martin Bohlmann was peaceful upon the land because he saw himself as small beneath the firmament. But his size was no diminishment. It was the beginning of wisdom. Martin was patient in creation because he believed himself to be an integral part of it all, a citizen of the universe, placed there by the wise Creator.

Faith and trust and farming were all the same to my father-in-law; therefore, he read the weather as humbly as he read the Bible, seeking what to obey. Martin was an obedient man, and his obedience was the source of his peace. Daily he did more than just read and interpret the rhythms of creation; even as Prince and Silver, heeding the farmer’s mute commands, moved in communion with him, so did Martin, obeying the signs of the Creator, enter into communion with God eternal.

Here is peace: not in striving for greatness but in recognizing who is truly great. And this is peace: by sweet humility to do the will of the Creator. This is peace: to bear the image of God into creation.

And this is peace: to know and to believe Isaiah’s words regarding grasshoppers.

Have you not known? Has it not been told you from the beginning? It is he who sits above the circle of the earth, and its inhabitants are like grasshoppers; who stretches out the heavens like a curtain, and spreads them like a tent to dwell in . …

Lift up your eyes on high and see: who created these? He who brings out their host by number, calling them all by name; by the greatness of his might, and because he is strong in power, not one is missing. (Isa. 40:21-22, 26)

As long as he worked the earth, Martin enjoyed an unbroken communication with the one who sits above the circle of the earth. He never doubted that he had a personal purpose and a sacred worth.

And this is peace: to know that this communication with the Creator could not even be broken by death.

A wonderful joke

In 1994, at the age of 94, Martin Bohlmann stuck a toothpick into his mouth, pushed back his chair from the supper table, stood up, and went outside. He strolled westward, into fields farther and farther beyond the land he rented—and there he paused. He stood a long while, his hands folded under the bib of his coveralls, growing ever darker in the twilight.In his own good time the farmer knelt down and scooped up a handful of the black earth. Then, when at last he let the soil blow out of his hands again, it was himself that blew upon the wind, the dust of his human frame and the lightsome stuff of his spirit. Never had there been much distance between the earth and his heart and the earth again.

Martin died in a perfect peace.

And when his family gathered around the coffin to view his body once before the burial, we saw a joke, a wonderful joke. His hair was still, stiff and tangled as barbed wire, his nose a majesty thrust upward from the polished coffin; and his old eyes were closed. But into the corner of our father’s mouth—to the deep distress of the mortician—someone had stuck a toothpick.

Walter Wangerin Jr. teaches theology, English, and creative writing at Valparaiso University. He published Paul: A Novel last autumn.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Learn how Calvin DeWitt is helping Dunn, Wisconsin, reflect the glory of God’s good creation through developing farms in Christianity Today‘s “God’s Green Acres.”Wangerin’s bio tells us that he is the author of more than 20 spiritual books for children and adults. A bibliography of Wangerin’s works is available from Regent College.

Wangerin himself teaches at Valparaiso University.

Wangerin and his wife Thanne share more about their family and marriage in Marriage Partnership‘s “Clearing the Air.”

Read “The Ragman“, a short story by Wangerin.

Wangerin discussed his Book of God and Bible interpretation on PBS’s News Hourin 1996.

Wangerin’s Book of God and Paul: A Novel are available from the Christianity Today bookstore.