Njoya, a Presbyterian, is at the forefront of an effort not only to rid the country of a corrupt government but to make the church as passionately committed to social justice as it is to church growth and biblical faith. He therefore often finds himself at loggerheads with elements in both church and state. Responding to criticism that the church has chosen sides in the country’s politics, Njoya freely admits that the church is the most partisan institution in the world. “The church is partisan against injustice, oppression, and dictatorship,” he said to the Nairobi newspaper The Nation.

“The Constitution should give us the right to hire and fire our governments,” Njoya added. “Instead, it has colonized us. Sovereignty does not belong to us. We have been denied that.”

On December 10, he received Canada’s prestigious John Humphrey Freedom Award for his efforts to strengthen human rights and democracy in Kenya.

The award, given each year by the Montreal—based International Center for Human Rights and Democratic Development, is named in honor of John Peters Humphrey, the Canadian who prepared the first draft of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“We hope that this international award will help provide some form of protection to Reverend Timothy Njoya, who has been targeted by the Kenyan police,” said Warren Allmand, president of the center. “He is an inspiration to all those who continue to struggle for peace, justice, and equality in Kenya.”

Tokunboh Adeyemo, general secretary of the Association of Evangelicals in Africa, calls Njoya an evangelical social prophet who, like “Desmond Tutu or Martin Luther King … is driven by a proper understanding of the demands of God’s kingdom here and now.”

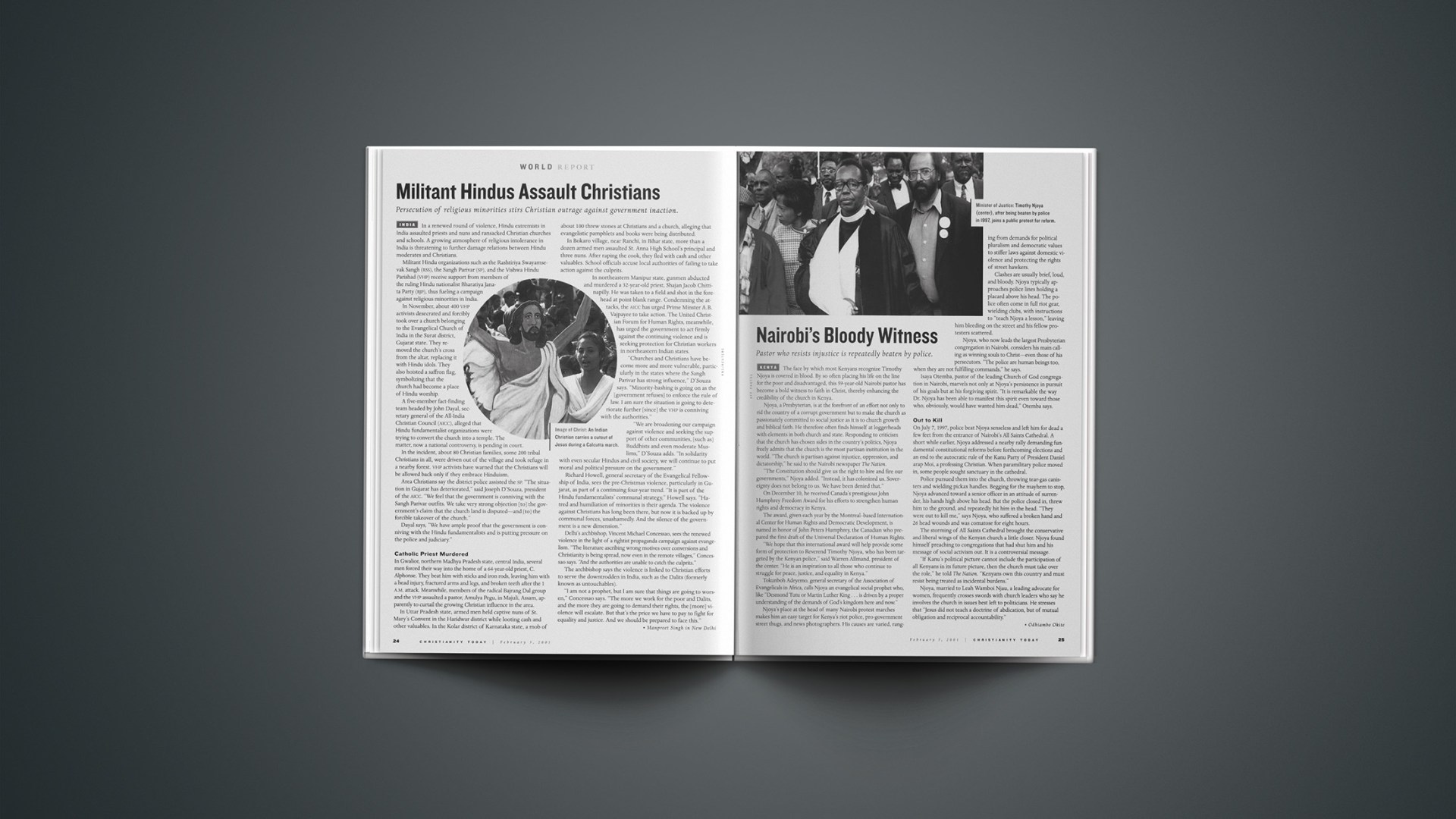

Njoya’s place at the head of many Nairobi protest marches makes him an easy target for Kenya’s riot police, pro-government street thugs, and news photographers. His causes are varied, ranging from demands for political pluralism and democratic values to stiffer laws against domestic violence and protecting the rights of street hawkers.

Clashes are usually brief, loud, and bloody. Njoya typically approaches police lines holding a placard above his head. The police often come in full riot gear, wielding clubs, with instructions to “teach Njoya a lesson,” leaving him bleeding on the street and his fellow protesters scattered.

Njoya, who now leads the largest Presbyterian congregation in Nairobi, considers his main calling as winning souls to Christ—even those of his persecutors. “The police are human beings too, when they are not fulfilling commands,” he says.

Isaya Otemba, pastor of the leading Church of God congregation in Nairobi, marvels not only at Njoya’s persistence in pursuit of his goals but at his forgiving spirit. “It is remarkable the way Dr. Njoya has been able to manifest this spirit even toward those who, obviously, would have wanted him dead,” Otemba says.

Out to Kill

On July 7, 1997, police beat Njoya senseless and left him for dead a few feet from the entrance of Nairobi’s All Saints Cathedral. A short while earlier, Njoya addressed a nearby rally demanding fundamental constitutional reforms before forthcoming elections and an end to the autocratic rule of the Kanu Party of President Daniel arap Moi, a professing Christian. When paramilitary police moved in, some people sought sanctuary in the cathedral.Police pursued them into the church, throwing tear-gas canisters and wielding pickax handles. Begging for the mayhem to stop, Njoya advanced toward a senior officer in an attitude of surrender, his hands high above his head. But the police closed in, threw him to the ground, and repeatedly hit him in the head. “They were out to kill me,” says Njoya, who suffered a broken hand and 26 head wounds and was comatose for eight hours.

The storming of All Saints Cathedral brought the conservative and liberal wings of the Kenyan church a little closer. Njoya found himself preaching to congregations that had shut him and his message of social activism out. It is a controversial message.

“If Kanu’s political picture cannot include the participation of all Kenyans in its future picture, then the church must take over the role,” he told The Nation. “Kenyans own this country and must resist being treated as incidental burdens.”

Njoya, married to Leah Wamboi Njau, a leading advocate for women, frequently crosses swords with church leaders who say he involves the church in issues best left to politicians. He stresses that “Jesus did not teach a doctrine of abdication, but of mutual obligation and reciprocal accountability.”

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Other media coverage of police brutality in Kenya includes:Human rights award ’embarrasses’ Kenya—Independent Online(Jan. 16, 2001)

Disciplinary Action Promised Following Police Attacks On journalists—AfricaNews (Jan. 6, 2001)

A voice unstilled—The Montreal Gazette (Sept. 4, 2000)

Previous Christianity Today articles about Kenya include:

Muslim-Christian Riots Rock Nairobi | Will religious fighting lead Kenya to convert to Shari’ah like some Nigerian states? (Dec. 27, 2000)

Kenyan Bishop Calls on Widows to Take Stand Against Wife Inheritance | Joter, polygamy customs criticized for contributing to spreading HIV. (Sept. 1, 2000)

Debt Cancellation a Question of ‘Justice’, Kenya’s Anglican Archbishop Tells Japan | Tokyo skeptical toward Jubilee 2000 message. (April 13, 2000)

Southeastern Seminary student beaten, robbed in Kenya | Family says not attacked because of Christianity, but it’s the reason they’re going back. (Jan. 10, 2000)

Toppling Tradition? | Christian teachings conflict with tribal customs, national laws. (Sept. 6, 1999)

Cursed by Superficiality (Nov. 16, 1998)