“Make yourself at home.” The pleasant young woman points to a loveseat in a small room. “This is the best way to appreciate Thomas Kinkade’s genius as an artist.”

My wife and I have happened upon Collector’s Corner Gallery on the village square in Pella, Iowa. Collector’s Corner, it turns out, is a furniture store that also sells lithographs and paintings, many of them by Kinkade, a kind of neo-Impressionist artist who bills himself as the “Painter of Light.” I make some offhand, dismissive comment to the effect that these lithographs are mass-produced for people who buy paintings to coordinate with the colors of the living-room sofa.

Melissa Slings, whose business card reads “Art Consultant,” gently disagrees and proceeds to offer an impromptu mini-course that might be called “Thomas Kinkade Appreciation 101.” Anyone who deals in Kinkade’s lithographs goes through a special training program to become a sales consultant, and she is prepared to, well, enlighten us.

Lesson one commences in the tiny, carpeted cubicle with the loveseat. A large, framed lithograph of Kinkade’s Lamplight Bridge hangs directly in front of us.

“Just sit back and relax,” Slings instructs, “and look at the painting.”

She reaches for the dial of a rheostat, which controls the track lighting in the small room. “Watch as the light dims,” she says, “and you’ll see the painting take on its own glow. It’s like magic.”

As the light wanes, the canvas assumes a kind of luminosity. The street lamps glow from atop their stanchions on the gentle arc of a stone bridge, and the cottage radiates a soft, buttery light from its mullioned windows. The effect is soothing and dreamlike, and in my reverie I have no difficulty imagining the residents of that cottage in denims, flannel shirts, and thick wool stockings stretched out in front of the fireplace, a favorite novel in one hand and a mug of steaming cider in the other, a yellow Lab at their feet and a Brandenburg Concerto playing softly in the background.

Magic, indeed.

Slings goes on to explain the elaborate coding that goes into every Kinkade painting. Kinkade includes a Bible reference and a fish (ichthus) with his signature, and he imbeds the letter N at least once on every canvas in honor of his wife’s name, Nanette. Occasionally the names and images of his four daughters or the visage of a friend will appear.

Placerville to Paradise

William Thomas Kinkade was reared in a single-parent household in Placerville, California, a small town in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. As early as age 4, he showed artistic promise. His mother encouraged him. Young Thom Kinkade would disappear for hours with his sketchbook and return with drawings of the natural beauty all around him.

“My whole life was absorbed with my art,” Kinkade recalled many years later. “I was known by my schoolmates as the kid who could draw.”

By his teen years he had discovered oils and worked as an apprentice to Glenn Wessells, a California Impressionist in the 1940s and 1950s.

Kinkade studied at the University of California, Berkeley, and at the prestigious Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, although he dropped out of both schools.

Kinkade, in his own words, “came to have a personal relationship with Christ” in 1980, while a student. His mother had reared him in the Church of the Nazarene, but an adolescent rebellion turned him away from evangelicalism. His involvement with Calvary Chapel in the early 1980s reconnected him to the faith of his childhood.

Kinkade and a college friend spent a summer traveling around the country, sketching scenery and collaborating on The Artist’s Guide to Sketching, which became a best-selling instructional book. The success of the book led to a stint in film animation, and Kinkade learned more about the effects of light. After the release of the film, Fire and Ice, Kinkade decided to devote his professional efforts to creating and marketing his own art.

About the same time, in 1982, he married Nanette, his childhood sweetheart.

Kinkade published his first print, Main Street at Dusk—Placerville, an idyllic rendering of his hometown, in 1984. Five years later he and a friend, Ken Raasch, founded Lightpost Publishing, which went public in 1994 as Media Arts Group Inc.

In 1995 he was named artist of the year by the National Association of Limited Edition Dealers, and for the ensuing three years Kinkade was designated graphic artist of the year by the same organization. In 1999 he was voted into U.S. Art magazine’s hall of fame.

“My paintings are halfway between a memory and a daydream,” Kinkade says in his spacious studio in a coastal mountain setting in northern California. “I try to produce a re-creation of the past without the hard edges.” The studio, awash in sunlight, has a huge, vaulted ceiling and a massive stone fireplace. “I wanted a place that felt like Yosemite,” he explains, “and I needed a big space because I’m working on some big paintings.”

Kinkade himself is a large man, expansive and eager to talk about his work and his faith. “My whole ministry is an expression of Matthew 5:16: ‘Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven,’ ” Kinkade says.

Kinkade calls himself the “Painter of Light” because of his Christian convictions. “Light is what we’re attracted to,” he says. “This world is very dark, but in heaven there is no darkness.”

Fresh from an early-afternoon jog and a shower, he sits on the edge of the fireplace, hunched forward, sipping from a glass of sparkling water. “Paintings are the tools that can inspire the heart to greater faith,” Kinkade says. “My paintings are messengers of God’s love. Nature is simply the language which I speak.”

Indeed, most of Kinkade’s art, including the work in progress at the other end of the room, depicts the natural world. Some of his paintings are representations of specific places, but most are composites of various scenes, images from the artist’s head.

“The ideas come out of nowhere,” he says, and some of the inspirations come from sketches he makes while sitting in church. Sometimes people will see a painting and tell him, “Yes, I’ve been there,” and then provide the name of a mountain range. “I have to correct them,” Kinkade says, “and admit that I made it up. I call them the Kinkade Mountains!”

With the practiced ease of an insurance agent listing his products, Kinkade ticks off the themes that animate his art: home, family, faith in God, the beauty of nature, celebration of romantic moments, a simpler way of living.

“I love to create beautiful worlds where light dances and peace reigns,” Kinkade says. “I like to portray a world without the Fall.”

From art factory to Kinkadeland

With its plush, dark carpeting and incandescent lighting, the reception area for Kinkade’s publishing house and warehouse looks like a living room in an upper-middle-class suburban home. “Lightpost Publishing,” the receptionist chirps into the phone. “Thank you for sharing the light.”

Several of Kinkade’s paintings line the wood-paneled walls. A display case holds samples of some of Kinkade’s licensed products: suncatchers, Bible totes, bookmarks, vases, a computer-screensaver package.

Denise Sanders, Kinkade’s assistant and my tour guide, ushers me into a conference room with still more Kinkade products: flower arrangements, a teapot, a collectible stein, a night light, notecards, a wastebasket/umbrella stand, a fountain, a lamp, Hallmark Christmas ornaments, a La-Z-Boy recliner upholstered with a fabric covered with N’s (for Nanette).

“People love these pieces,” Sanders says, “because they hit all the price points.”

Indeed, there seems to be no limit to the licensing possibilities for Kinkade’s work. Inserts in newspapers regularly advertise Kinkade commemorative plates and Thomas Kinkade’s Lamplight Village: “Meticulously handcrafted and carefully handpainted for exceptional realism.”

If a licensing arrangement with Taylor Wood row Homes goes as planned, it may soon be possible to live in a full-scale Kinkade village. The company recently broke ground on a 100-unit residential development in Vallejo, California, “entirely themed” from Kinkade’s paintings, with lampposts, gardens, and gazebos.

“We’ve designed the entire community as close as possible to the feeling and flavor of the paintings,” says Raffi Minasian, senior director of licensing and product design at Media Arts Group. The houses, which will cost in the mid-$300,000 range, will be built in the English country garden style, with the interiors designed, Minasian says, “to promote family interactions.” They will be decorated top to bottom with Kinkade paintings, furniture, and accent pieces.

Further back into the San Jose warehouse, which covers 100,000 square feet, past racks full of canvases in various stages of production, Sanders shows me how the Kinkade magic evolves. After the artist completes one of his paintings (at a rate of approximately one a month) it is rushed into production—or, rather, reproduction. Digital cameras photograph the original, and the lithographs come to a room in the warehouse where workers, using a special process, mount the lithograph onto a canvas, thereby approximating the look and texture of an original painting.

The next step is Kinkade’s innovative method of highlighting. Most of the pieces move into a roomful of easels where artists, seated side by side at a long table, apply dots and squiggles of particular colors to places on each canvas that Kinkade has specified, thereby rendering a three-dimensional feel to the canvases.

A few of the pieces, however—those designated for higher prices—move into the studios of what the company calls “master highlighters,” more highly skilled artists who have been specially trained by Kinkade himself. These “Renaissance Editions” fetch about $6,000 per copy.

Canvases highlighted by Kinkade himself command anywhere from $30,000 to $60,000 each.

Farther back in the warehouse, other workers place the highlighted paintings into frames and tack on brass plates with the title of the painting and the artist’s name. The warehouse, which employs approximately 400 workers, produces and ships 700 to 1,000 framed and highlighted pieces a day. Kinkade has imposed elaborate quality-control checks at every point in the process, from the arrival of the lithographs to shipping. In most cases, anything that falls short of the standards is destroyed, although the company occasionally offers an imperfect piece to employees at a reduced price.

Some of the reproductions go directly to consumers, especially those who are members of the Thomas Kinkade Collectors’ Society, but most go to company-owned galleries or to one of approximately 200 “signature galleries” around the country. These are specially licensed stores, most of them located in shopping malls, that sell only Kinkade merchandise.

The whole operation is slick and professional. Media Arts Group is traded publicly on the New York Stock Exchange. The company rang up more than $120 million in sales during the 2000 fiscal year. Kinkade’s stake is something like 3.1 million shares, which has made him a very wealthy man.

Art evangelism

“A few years ago I looked at my savings account and at the various blessings God has given me,” Kinkade told an interviewer in 1999, “and I realized that from a material point of view, there wouldn’t be any more reason I would have to work.” The artist, 41 at the time, continued his thought. “At that point, you have to work out some other drive. And the drive is not material. The drive is not commercial success. The drive is utilizing whatever talent you have to bless others.”

Kinkade’s commercial prowess as “America’s most collected artist” has allowed him to think more broadly about what he wants to do with his success.

“I want to use the paintings as tools to expand the kingdom of God,” he says. Several years ago, Kinkade entered into an arrangement with the humanitarian agency World Vision whereby if people sponsored a child for a year, they would receive a Kinkade print.

“I grew up in poverty by this culture’s standards,” he explains, which is why he feels a special affinity for World Vision.

Kinkade calls the marketing scheme “leveraged giving,” and World Vision has seen a dramatic increase in contributions. Marty Lonsdale, vice president for marketing at World Vision, says Kinkade’s “generous gift of a print has influenced many thousands of people to give to World Vision, and these donors have demonstrated a high degree of commitment to our ministry.”

Kinkade’s other plans are more ambitious. “Art as a form of expression in Western society is dying,” he said, taking another sip from his sparkling water. He cites the fact that art programs are subject to budget cuts in schools around the country, even in artist colonies like Carmel-by-the-Sea, just a few miles down California Highway 1 from San Jose. Kinkade wants to design an art curriculum for the schools, one that avoids the depredations of Modernism and emphasizes the development of traditional skills.

“Art is not an option,” Kinkade says. “I want to build the new iconography for the coming millennium.”

The word millennium has particular meaning for Kinkade. One of his recent paintings is called Sunrise: A Prayer of Hope for the Millennium of Light to mark the turn of the 21st century.

“I believe Jesus is coming again in this new millennium,” he says matter-of-factly. “Our life is like a vapor.”

Kinkade’s sense of living in the last times lends an urgency to his agenda. “Art transcends cultural boundaries,” he says. “I want to blanket the world with the gospel through prints. This is a very thoroughgoing form of evangelism.”

He notes that 10 million people have already brought Thomas Kinkade into their homes. “A painting is a presence in the house,” he says, and he believes that his paintings are “messages of God’s love” that will be handed down through the generations. Kinkade points to one of his prints hanging in the studio. “Paintings are the tools that can inspire the heart to greater faith.”

Kinkade’s portrayals of sylvan cottages and cobblestone pathways and garden gazebos are much more, in the artist’s judgment, than pretty pictures. They are powerful weapons in the war against unbelief and, more particularly, against the corrosive effects of Modernism.

“I see a campaign for culture shaping up around me,” he says. “Art is the hot button in the cultural battle at play right now.”

Kinkade leans forward, his voice rising in intensity. “The disintegration of the culture starts with the artist,” he says. “In a way, Modernism in painting is responsible for South Park and gangsta rap.

“I’m on a crusade to turn the tide in the arts, to restore dignity to the arts and, by extension, to the culture.”

Kinkade draws a deep breath and proceeds to outline his battle plan. The first step, already accomplished, was to promote himself as the most commercially successful artist in the culture. “We wanted to create the first mainstream superstar,” he says.

Second, he built a highly successful corporation around himself, with lucrative licensing arrangements and its own manufacturing plant that produces what he calls “semi-originals” for distribution throughout the world.

Resisting the Modernist lie

Now, using the financial resources that have accrued from steps one and two, Kinkade has embarked on the third phase of his campaign. He has established the Thomas Kinkade Foundation as a way to resist, in the artist’s words, “the art culture that is so inbred.”

Kinkade characterizes the work of the foundation as “a form of sabotage,” and he lapses into militaristic imagery: “I view it as a Trojan horse that we’re sending into the enemy camp.”

When the subject of modern art comes up, Kinkade becomes even more animated. He opens his riff with Pablo Picasso’s remark, “I came to destroy beauty.”

“The whole Modernist lie is that art is about the artist,” which has led to contempt for the audience, Kinkade says. It has also led, he believes, to what he calls the “fecal school” of art, or “bodily function” art, a reference to the work of Rob ert Mapplethorpe and to a controversial 1999 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, which featured a depiction of the Blessed Virgin surrounded by elephant dung.

The travesty of Modernism, Kinkade believes, is that it has become an “inbred, closed culture.” The result of Modernism’s contempt for the audience, he insists, is that museums are dying.

At this point, Kinkade’s plan becomes audacious. He claims that just as the Impressionists of the late 19th century reacted to the “dead art” of the preceding era, so too his own work brought light back into the art world late in the 20th century. Now he aspires to encourage other artists. He wants to establish what he calls the Academy of Traditional Art, which would recognize traditional artists for their contributions to the culture, perhaps with an Academy Awards-style presentation.

He also wants to erect a series of alternative museums. “I don’t want to clean up the outhouse, to close the Whitney,” he says. “I want to build a temple next door.” Kinkade draws a contrast between the sterility of modern art galleries and museums and the comfortable ambience of his galleries, with soft lighting, wood paneling and deep-pile carpeting. “Walk into one of our galleries,” Kinkade says, “and you’re at home.”

Highbrow enemies

The Whitney Museum of American Art, located at Madison Avenue and 75th Street in New York City, opens its doors without charge to the public on Friday evenings at six o’clock. Outside of the entrance and at several places in the lobby, the museum has posted warning signs, black letters on an orange background:

PLEASE NOTE Some of the art work in “Alice Neel” and “Barbara Kruger” may not be appropriate for children.

The exhibit on the top floor offers a kind of retrospective of modern art, Art in America from Hopper to Pollack, featuring pieces from the Whitney’s collection. The artists represented here range from Edward Hopper and Thomas Hart Benton to George Bellows, Jackson Pollack, Alexander Calder, and Georgia O’Keefe.

The retrospective leads from urban realism to gestural painting and early abstract expressionism.

I am particularly struck by a small painting by Peter Blume, Light of the World, 1932. The piece depicts several people gazing dumbfoundedly, even worshipfully, at a large, light bulb-like contraption, which is clearly meant to represent the wonders of technology and Enlightenment rationalism. In the background stands a medieval church, its windows darkened and its doors closed, with a beleaguered, distressed-looking monk taking in the scene.

Further in the background is a pastoral scene very much like one that Kinkade might paint, but the central characters have their backs turned against that tableau, the church and the Technicolor sky, so enraptured are they by the marvels of modernity and technology.

The exhibition of the works of Alice Neel, a bohemian figure in New York’s Greenwich Village and Spanish Harlem, marks the centennial of the artist’s birth. Neel’s portraits of various friends, lovers, and acquaintances show a lot of frontal nudity (male and female). Her palette is dark and brooding, and some of the characters have an almost feral look to them. The Neel exhibition, with its odd constellation of characters, might be seen as a chronicle of the breakdown of the nuclear family.

The Barbara Kruger exhibition is a calculated assault on the senses. Her signature is black-and-white photographic images overwritten with white block letters reversed out of red banners. Kruger’s most famous image, designed for the 1989 March on Washington in support of women’s rights and the abortion-rights movement, is a photograph of a woman’s face, the image half-negative and half-positive, overwritten with “Your body is a battleground.”

Other works in the exhibition lampoon intolerance, consumerism, and religious belief: “How dare you not be me?”; “I shop, therefore I am”; “My god is better than your god. Wiser, more powerful, all-knowing, the only god.” A photograph of a serpent-handler bears the caption, “Believe like us,” while a preacher rants on an audio track. Kruger’s work is unrelentingly cynical, violent in its own way.

This is not so much art as assault, with more than a little hypocrisy thrown in: Kruger’s tirades against consumerism have been silk-screened onto T-shirts, which are available for purchase in the museum store.

In its own way, however, Kinkade’s art is just as tendentious as Kruger’s. Kinkade insists that there is goodness and beauty in the world, beauty that is worthy of celebration and replication. The created order, his work declares, has redemptive power. It can soothe and heal, as anyone who has climbed a mountain or paddled a canoe in deep waters will attest. Kinkade’s paintings bring a representation of creation into the living room, a representation relatively unfiltered by contemporary artistic conventions.

Kinkade’s critics—and he does not lack critics—fault him precisely for that, for flouting contemporary artistic conventions.

“He doesn’t look like an artist who’s worth considering,” sniffs Robert Rosenblum, a curator at the Guggenheim Museum, “except in terms of supply and demand.” Other critics use adjectives like “cheesy” and “clumsy,” and phrases like “slickly commercial kitsch.”

Jack Rutberg, an art dealer in Los Angeles, told The Wall Street Journal that Kinkade’s paintings are “the pet rock of the art world.” Kenneth Baker, art critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, asks, “Do we want what we call ‘art’ to serve this social function of quelling our anxiety in an almost pharmaceutical fashion?”

Kinkade remains unmoved by his critics, and he may have found an unwitting ally in Phillippe de Montebello, the redoubtable director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In an op-ed piece in The New York Times, de Montebello lamented that “so many people, serious and sensitive individuals, are so cowed by the art establishment or so frightened at being labeled Philistines that they dare not speak out and express their dislike for works that they find either repulsive or unaesthetic or both.”

Kinkade himself puts it differently. “High culture is paranoid about sentiment,” he told the Times. “But human beings are intensely sentimental. And if art does not speak a language that’s accessible to people, it relegates itself to obscurity.”

Kinkade’s populist sentiments mirror that of evangelicalism more generally. One of the hallmarks of evangelicalism, especially in America, is its disdain for pretension and high culture, its ability to speak the idiom of popular culture, be it the colloquial hymns of the 19th century, the folksy cadences of Billy Graham, or the food courts of suburban megachurches. Evangelicals like Kinkade care little for the approbation of the cultural elite.

“The critics may not endorse me,” Kinkade says defiantly, “but I own the hearts of the people.”

Life before the Fall

For anyone familiar with Kinkade’s work—and given the reach and the marketing savvy of Media Arts Group, it would be difficult to imagine anyone who is not at least dimly aware of his work—it will come as no surprise that Norman Rockwell was a major and formative influence for Kinkade.

“Whether you’re looking at a snow-frosted scene of Christmas Eve churchgoers, a tiny thatched-roof cottage in England, or a rambling old Midwest farmhouse, you can sense that each Thomas Kinkade painting portrays some delightful, storybook charming place he would love to share with his adoring daughters,” Kinkade’s promotional materials read. “The love, care, and beauty shines through each image he shares.”

Just as Rockwell sought to depict the delights and the quirkiness of small-town life that he knew was dying in the age of mass communications, fast food, and Interstate highways, so too Kinkade offers sylvan landscapes accessible only to the imagination.

“A piece of art is a compact form of the universe,” Kinkade says. “I try to make the world comfortable and understandable.”

There are surely differences between the two men. Rockwell depicts life before television sitcoms and before Ray Kroc decided that all Americans had an inalienable right to a Big Mac; Kinkade evokes a world before Eve and Adam developed a craving for apples. Rockwell was also the master of character, the small, telling detail or expression—comic or poignant or both—while Kinkade studiously avoids anything that might remotely resemble portraiture or caricature. When people appear in his paintings, which they rarely do, their visages are nearly always blank or nondescript, almost like an Amish doll.

“That’s so the viewers can imagine themselves into the scene,” says Sanders, his assistant.

Despite their stylistic differences, both Kinkade and Rockwell provide glimpses into a world that is not surreal (as with some forms of modern art), but unreal. Kinkade’s landscapes invite the viewer, in the artist’s words, to “imagine a life where there is plenty of time, plenty of energy, plenty of opportunity for everything you feel is important—plus a little left over for some things you simply enjoy.”

His paintings provide shelter, a kind of enwombing. The space Kinkade portrays is female space, characterized by interiority. There is nothing angular in his paintings; the lines are soft and rounded and inviting.

This art is quintessentially evangelical not only in its populism and use of Bible verses, but also in its interiority. Just as evangelicals emphasize an inward piety over outward forms—”invite Jesus into your heart”—the light in Kinkade’s paintings has been tamed and domesticated and internalized.

The art of Thomas Kinkade offers an oasis, a retreat from the assaults of modern life, a vision of a more perfect world. Who wouldn’t like to catch a glimpse of that world from time to time, to picture life before the Fall?

But we live and move and have our being in a fallen world, and it is our lot as human beings to negotiate that world. Kinkade’s paintings furnish little guidance for that enterprise (other than to remind us that goodness and beauty once prevailed on earth), but that may be too much to ask of any artist. Although viewers can imagine themselves in Kinkade’s paintings—cross-legged in front of the campfire, meandering through luxuriant gardens, sitting down to a Victorian Christmas dinner or cozying next to the fireplace—they still stand outside the frame. Despite the artist’s evocative talents, Eden remains elusive—even, I suspect, in the Kinkade village under construction in Vallejo, California.

Randall Balmer is the Ann Whitney Olin Professor of American Religion at Barnard College, Columbia University. Oxford University Press released the third edition of his book Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory in November.

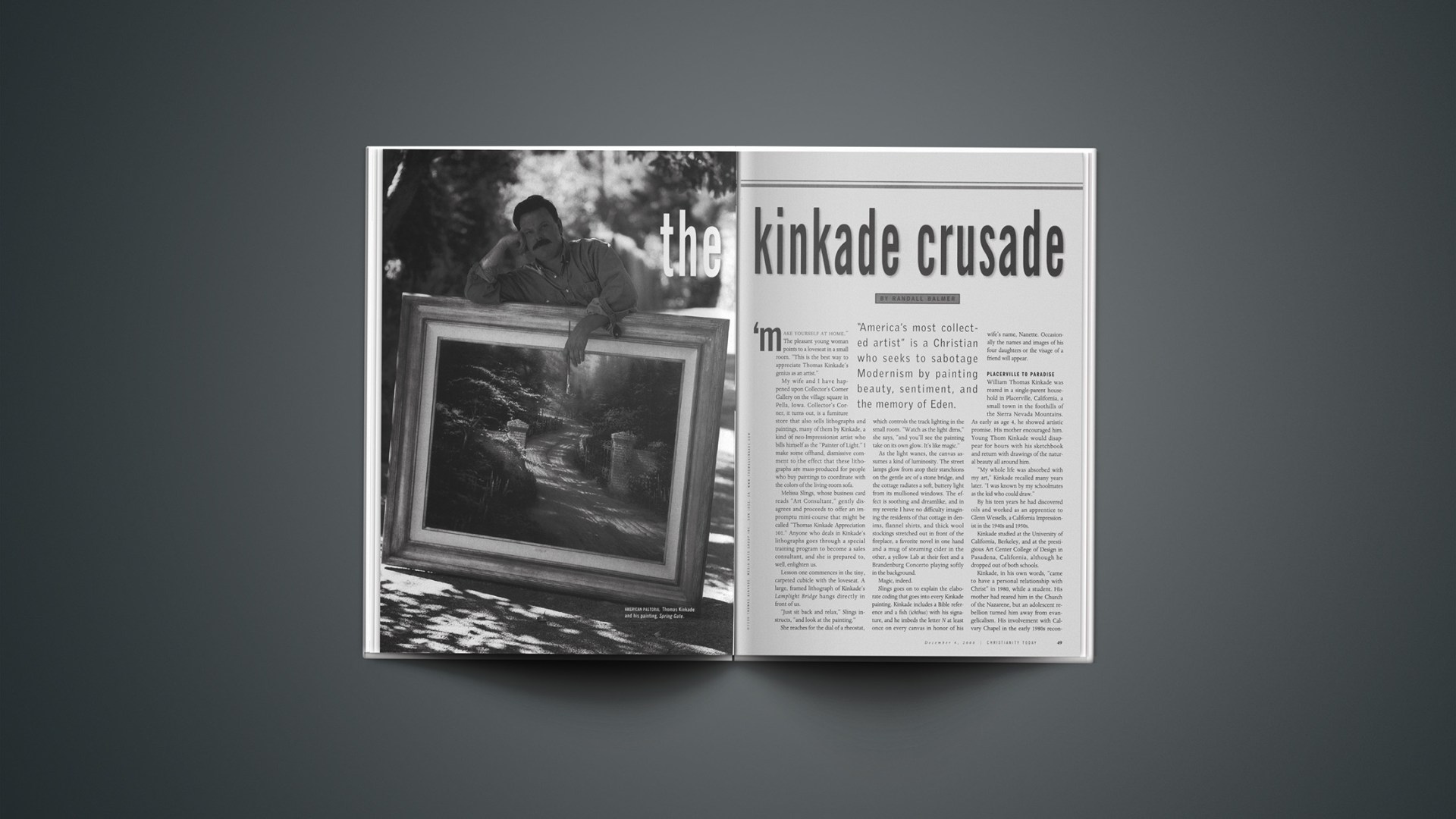

Photography by Media Arts Group

Related Elsewhere

See today’s related Christianity Today editorial, “The Artist as Prophet | What is Christian art, and what does it look like?”

Visit Kinkade’s Web site where you can purchase his work and read a short biography.

Kinkade was named the National Bible Week spokesperson of 2000.

View some of Kinkade’s scripturally-inspired paintings.

Read Flak magazine’s critique of the marketing strategy behind Kinkade’s profits. The [Colorado Springs] Gazette brings up similar questions in an August feature.

Time magazine featured Kinkade in its August 30, 1999, issue. USA Weekend featured him in February.

Kinkade worked with World Vision to offer a free print to people who sponsored needy children.

Read World Vision’s Today magazine interview with Kinkade.

Previous Christianity Today articles by Randall Balmer include:

Hymns on MTV | Combining mainstream appeal with spiritual depth, Jars of Clay is shaking up Contemporary Christian Music. (Nov. 1, 1999)

Still Wrestling with the Devil | A visit with Jimmy Swaggart ten years after his fall. (Mar. 2, 1998)

Hollywood’s Renegade Apostle | Unless films like The Apostle succeed, other worthy motion pictures stand little chance of being produced. (Apr. 6, 1998)

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.