When the huge new building was finished, nobody in the Chicago area thought it looked like a church. On the outside it looked like a convention hall, on the inside like a 5,000-seat theater. And what went on inside didn’t seem much like church either. The first thing visitors noticed was the music, which was lively, contemporary, and professional.

On any given Sunday the audience was as likely to see a play as hear a sermon. And then there was the preacher—dressed in ordinary clothes, he was breezy and compelling; by turns funny and serious; and always utterly irresistible. Critics sniffed that this was entertainment, not worship. Truth be told, it was entertaining. The thousands of casually dressed people who jammed the parking lot and streamed into the building looked less like churchgoers and more like Cubs fans headed for Wrigley Field.

And what happened on Sunday was only the sauerkraut on the kielbasa. The rest of the week dozens of paid staff and even more volunteers organized media productions, prayer services, men’s and women’s groups, boys’ and girls’ clubs, summer camps, and food programs for the needy.

They operated a 100-seat restaurant inside the church building, supported dozens of missionary agencies, and ran an extensive small-group ministry that spread throughout the Chicago area.

The idea behind all this was to create a new kind of nondenominational church that would use an interesting program and comfortable surroundings to draw in the unchurched. Once drawn in, they would be enveloped in a comprehensive network of activities designed to give them a supportive community and deeper instruction in the Christian faith. This approach was so successful in Chicago that it immediately spawned a host of imitators in many parts of the country, who then formed an association of like-minded churches to strengthen and spread the movement.

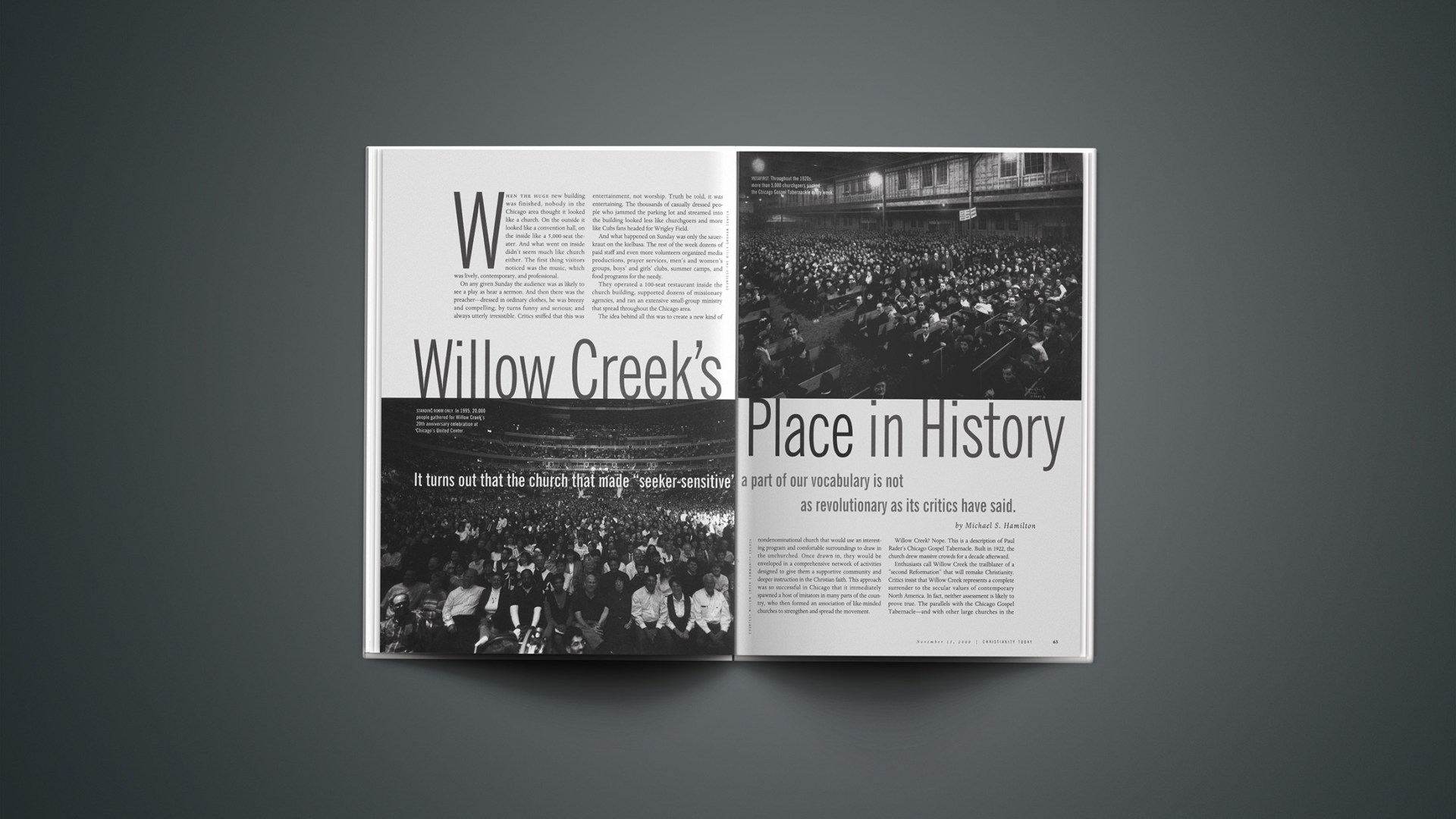

Willow Creek? Nope. This is a description of Paul Rader’s Chicago Gospel Tabernacle. Built in 1922, the church drew massive crowds for a decade afterward.

Enthusiasts call Willow Creek the trailblazer of a “second Reformation” that will remake Christianity. Critics insist that Willow Creek represents a complete surrender to the secular values of contemporary North America. In fact, neither assessment is likely to prove true. The parallels with the Chicago Gospel Tabernacle—and with other large churches in the past—suggest that Willow Creek is not so much charting new territory as it is traveling along one of the main arterials of American evangelicalism.

Willow Creek’s uniqueness lies in the circumstances in which it finds itself—and in the way it has built a ministry to meet those circumstances. But its building materials have been around for a long time.

For a century now, self-confident preachers have been willing to reinvent church in order to appeal to the unchurched. They have used nonsacred architecture, innovative worship services, popular music, drama, and diverse programming to meet the needs of people who felt unwelcome in traditional churches. And a few of these new churches—to the surprise and dismay of the traditionalists—grew really large.

The first megachurches

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, churches faced a massive wave of immigrants flooding into the cities. In 1914 one in three Americans was an immigrant or the child of an immigrant. In a few cities, the foreign-born outnumbered the native-born two to one. Newcomers displaced older residents in downtown districts, and downtown churches had to choose: follow their parishioners uptown or modify their ministry so that the newcomers would feel welcome. Many churches stayed, and the “institutional church” movement was born.

Like Willow Creek, the institutional churches began by listening to their new neighbors. What did they need? What might get them to come to church? In response to what they heard, they built churches that didn’t look like churches. Many looked like warehouses; St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal in New York was a nine-story building with a rooftop garden.

They didn’t look like churches because they included new kinds of facilities for new kinds of ministry—gymnasiums, swimming pools, medical dispensaries, employment centers, loan offices, libraries, daycare centers, and lots of classrooms. Critics invariably complained that their worship spaces seemed to be an afterthought, but these buildings were designed for seven-days-a-week service.

Institutional churches did away with pew rentals—the system in which the wealthiest families got to reserve pews up front while the poor sat in the back—which in those days was the main revenue source for urban churches. (Contemporary megachurches that want to recapture this lost tradition might consider auctioning off the good parking spaces!)

They held services in several languages. Some dispensed with hymnals and projected song lyrics on the wall. They taught English, hygiene, home economics, and work skills. They showed movies, held lectures, and sponsored concerts.

Shaping ministry programs around the needs of their neighbors made some of these churches huge. St. Bartholomew’s employed 249 paid workers and 846 volunteers serving nearly 3,000 members and countless local nonmembers. Russell Conwell’s 3,000-member Baptist Temple in Philadelphia built a hospital and a university (Temple University) as well as a large new church. And William Rainsford’s St. George’s Episcopal in New York City had over 6,600 people involved in its parish ministries. Soon these churches banded together and formed the Open and Institutional Church League, and their example was copied in cities all over the United States.

Show of shows

The Roaring ’20s were Paul Rader’s heyday, and the innovative character of the Chicago Gospel Tabernacle was matched by other nondenominational evangelical churches. The most famous was Aimee Semple McPherson’s 5,300-seat Angelus Temple in Los Angeles, which at its peak pulled in more than 10,000 people every Sunday. Willow Creek’s effective use of drama in its services has attracted a lot of attention, and rightly so. But compared to McPherson’s productions, Willow Creek’s are much less dramatic. Angelus Temple did not have a pulpit, it had a stage, and on its stage Sister Aimee brought to life the glories of heaven, torments of hell, and the allure of the fleshpots of Egypt. Live sheep and camels, ships filled with musicians, roaring motorcycles, screaming sirens, and elaborately costumed casts of dozens were regular fare inside the Temple.

Whenever Sister Aimee premiered a new “illustrated sermon” on Sunday night, Angelus Temple was lit up like a Las Vegas casino. Searchlights swept the sky above the traffic jams, while specially scheduled trolley cars disgorged passengers, and thousands stood in line for hours hoping to get a seat.

Willow Creek’s critics often deride its large variety of ministries as “shopping mall” Christianity, but large churches used this approach to ministry long before shopping malls had been invented. Before the turn of the century, institutional churches each sponsored dozens of ministry activities. The same was true of the Gospel Tabernacles. Angelus Temple boasted that it had “something for everyone”—weekday noon services around the city, a slew of youth groups and youth crusades, choirs, orchestras, parades, prayer ministries, healing services, adult classes, courses for new believers, radio broadcasts, a magazine, and, of course, production of the illustrated sermons.

Other large evangelical churches, including those affiliated with denominations, took the same approach that Sister Aimee did. In Seattle, the 9,000 members of Mark Matthews’s First Presbyterian Church helped operate the church’s radio station, hospital, and Bible institute. In Chicago, L. K. Williams’s 12,000-member Olivet Baptist Church had 30 paid staff and hundreds of volunteers to run the church’s Sunday school, labor bureau, soup kitchen, adult education classes, medical clinic, nursery school, and kindergarten. And at Hollywood Presbyterian in southern California, Henrietta Mears used multiple ministries to build a 4,000-member Sunday school in just three years.

In 1950, a writer for The Christian Century reported in amazement that Hollywood Presbyterian was sponsoring a bewildering array of over 300 “societies, classes, groups, clubs, auxiliaries, fellowship teams, choirs, camps, circles, flocks, and what have you.”

The rise of “undenominationals”

Denominations mean less to American churchgoers than ever before, so Willow Creek was in a perfect position for a long ride on the nondenominational wave that began to swell in the 1960s. But the idea of nondenominational Christianity has been attractive to many Americans all through the 20th century.

On the evangelical side, the gospel tabernacles were not the only churches to mine this vein of American religiosity. In the late 1920s in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Martin DeHaan converted his Calvary Reformed Church (Reformed Church in America) to Calvary Undenominational Church and drew in more than 2,000 people every Sunday.

William McCarrell pulled his Chicago-area church out of the Congregational fold and renamed it Cicero Bible Church. In 1930 he founded an association of similar churches, the Independent Fundamental Churches of America (IFCA). Over time, the IFCA evolved from an association of nondenominational churches into a denomination, but at first it was merely a fellowship of like-minded churches.

On the liberal side, a number of talented pastors also founded large churches on a foundation of nondenominationalism. When John D. Rockefeller built Harry Emerson Fosdick a grand new church in New York City, Fosdick insisted that it had to be nondenominational. For the next 16 years, crowds packed Riverside Church to hear Fosdick preach and to participate in its extensive ministry activities that combined the best features of both institutional and evangelical churches.

In a suburb just outside of Columbus, Ohio, First Congregational had already become the nondenominational First Community when liberal Roy Burkhart took over in 1935. In his 23 years there, Burkhart built a 3,400-member church with his strong emphasis on lay-led ministry. This included youth programs, home fellowship and Bible-study groups, men’s and women’s societies, visitation programs, a large personal counseling center, social services for the poor, help for unwed mothers, a radio broadcast, and special programs to “help members find their place in the whole church program.” Burkhart also built attention-getting entertainment into the program. Rader and Sister Aimee would have agreed with Burkhart when he once said, “You’ve got to have a little showmanship if you would be a successful minister.” (However, in his book discussing how he grew such a large church, he somehow never got around to mentioning one other crucial element—he had persuaded the city council to pass zoning laws prohibiting other churches from locating in the area.)

Underlying Burkhart’s philosophy of ministry was his conviction that nondenominational churches were the wave of the future, and he promoted the spread of such churches through the Association for Community-Centered Churches.

That association exists no more, but Burkhart’s assessment was right on the money. American Protestants, in larger and larger numbers, now prefer nondenominational churches, and Willow Creek and others like it are the beneficiaries of this shift.

This is also having a profound impact on denominational churches. Sociologist Scott Thumma of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research has found that most denominational churches that are megachurch size (2,000-plus attendance) have downplayed their denominational identity. For instance, Granger Community Church in northern Indiana—a Willow Creek lookalike—is part of the United Methodist Church, but there’s no way to tell that from its signs, advertisements, or Web site.

The widespread loosening of denominational ties has enabled Willow Creek’s ideas and methods to spread far beyond the “community church” movement into the denominations.

Looking for the best producers

Behind Willow Creek’s broad influence is a major pendulum swing in the role of American denominations. Transplanted to North America as European state churches and groups that dissented from the state churches, their American descendants—what we call denominations—had to find a new reason for being in a context where state churches had been abolished. Their initial response was to provide services for local churches, chiefly by establishing institutions to train, ordain, and sustain clergy.

Through most of the 19th century, denominations were modest organizations. But in the late 19th century, the pendulum swung away from the local church toward the denominational headquarters. In the same years that John D. Rockefeller turned Standard Oil into the most aggressive monopoly in the world by centralizing control over every aspect of the oil industry, the Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and others all expanded their national bureaucracies by taking control over a larger share of ministry activities. It wasn’t long before denominational officials began to think of themselves, not the local clergy, as the frontline workers in the church.

In this new configuration, the purpose of the local church was to support the denomination’s centralized program, not the other way around.

Records from the early 20th century are embarrassingly full of evidence that denominational bureaucrats thought of churches as local production units whose purpose was to generate income for the real work of the denomination that they—the bureaucrats—were trying to do. They hired efficiency experts to determine which kinds of churches produced the most income and then developed plans to encourage more of that kind of church. And increasingly they evaluated local pastors on their records of producing income for the headquarters. The best producers got the best appointments.

This was the period in which denominational officials learned how to manage appointments, committees, and information flows to obtain maximum autonomy for themselves and their enterprises. Naturally, local pastors complained about denominational insensitivity to local needs. But the managers, jealously watching the financial returns from the churches, chided the complainers for their “parochialism” in “neglecting the larger work of the church.”

Nondenominational domination

The managers won the battles for control of the denominations, but they lost the war for control of American church life. Now the pendulum has swung back. Independent churches are flourishing, and churches within denominations are asserting their autonomy as never before.

The arena in which they claim autonomy varies. Some churches have diverted money from their denomination’s missionary program to their own handpicked missionaries; others have performed homosexual weddings in defiance of the denomination. A few denominational officials still complain about the “selfishness” of local churches, but most of them have figured out that hardly anyone in the churches is listening. The new localism has forced denominations to start redefining themselves as servants, not masters. They’ve slashed central office programs, laid off staff, and begun to strengthen programs that directly support the local churches.

Some pastors of denominational churches have asserted their autonomy by remodeling themselves after Willow Creek. So in 1991 Bill Hybels and colleagues founded the Willow Creek Association (WCA) to teach other churches what his church had learned. The Willow Creek Association is perfectly attuned to the new localism in American Protestantism. It offers conferences and workshops, books and curriculum, video and audio tape series, newsletters, and other networking materials that allow churches to benefit from Willow Creek’s experience and keep in touch with other churches in the association.

For $249 per year, any church that affirms a commitment to “a historic, orthodox understanding of biblical Christianity” can join the WCA and receive the newsletters, and discounts on workshops and products. The WCA does not look much like a denomination-in-the-making for the simple reason that most of its member churches remain either staunchly independent or firmly tied to their original denominations. This is a very different thing from the status of churches in two new denominations that grew out of other evangelical megachurches—the Calvary Chapel Association and the Association of Vineyard Churches. Both of these train and ordain pastors, their member churches don’t belong to other denominations, and their churches mostly have similar ministry emphases.

By contrast, even the WCA’s own claim that it is a “network of like-minded churches” is overstating the matter by quite a bit. In one region, for example, WCA members include a couple of Willow Creek wannabes but also a couple of nonevangelical mainline churches and one church from a traditional African-American denomination. Anyone who uses the WCA’s membership list from its Web site to try to locate a church like Willow Creek might be in for a surprise.

It’s probably more accurate to think of the Willow Creek Association as a parachurch organization providing a proprietary product line. The WCA membership is really a client list of 3,300 churches in the U.S., 200 in Canada, and perhaps another 2,500 or so outside North America. It also appears that most WCA members are churches that are not yet large but want to grow.

Conspicuously absent from the membership list are well-known megachurches—in other words, churches that don’t need to learn Willow Creek’s techniques. At least one such church is in the process of developing a service organization designed to compete with the WCA: Rick Warren’s 15,000-member Saddleback Valley Community Church, located south of Los Angeles, sponsors Purpose-Driven Ministries.

Like Willow Creek, Saddleback began with a demographic survey and built itself up using seeker services. And like the WCA, Purpose-Driven Ministries (PDM) sponsors conferences and produces teaching materials to help churches learn from Saddleback’s successes.

But there is one huge difference between PDM and the Willow Creek Association. Purpose-Driven Ministries unblushingly preaches technique. Its conferences, workshops, and teaching materials give clients a specific formula designed to replicate the Saddleback experience. To reinforce the message that the formula works, PDM gives annual awards to churches that achieve outstanding results by following the program.

To the leaders of Willow Creek, this is like asking the caboose to pull the engine. Churches of ten want to grow for selfish reasons, and Willow Creek will have nothing to do with that. Its leaders insist that churches need to shift their concern from programming and growth to the real needs of those they are called to serve. Willow Creek’s ultimate goal is not to grow churches, nor to spawn a thousand imitators; it is to renew Christianity by encouraging every church to focus on the people to whom God has sent it.

What does the future hold?

In its day the institutional church movement was the sensation of the American church scene, and the best churches grew to phenomenal size. But by the 1920s, the movement had little life left in it. Institutional churches originally had used social service as an evangelistic tool, but as the 20th century advanced, they dropped evangelism in favor of mere humanitarian service. The result? Congregations dwindled while budgets mounted. Some churches became purely social agencies whose functions were taken over by government. Others relocated and reverted to more traditional forms. And others simply closed.

Later, Paul Rader’s Gospel Tabernacle was one of the most innovative and widely imitated church movements. But by the mid-1930s, the Depression had so crippled the Tabernacle that it became just another Chicago church.

A few of the gospel tabernacles continued to thrive after the Depression. Under the leadership of Bascom Ray Lakin, the Cadle Tabernacle of Indianapolis continued to draw in excess of 10,000 people weekly well into the 1950s.

The excitement surrounding Angelus Temple faded during the 1930s, but the new denomination it birthed grew and prospered as the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel. By the mid-1990s, it included 27,000 churches in North America and 25,000 abroad.

Nevertheless, by and large the urban gospel tabernacle as a dynamic, growing movement was by and large spent. Too many people were moving out to the suburbs, and cultural tastes were changing. Christian vaudeville in buildings that looked like big steel tents no longer had the drawing power it once did.

In the prosperity of the 1950s, many mainline leaders tried to advance at the local level their long-cherished hope of institutional unity. Roy Burkhart was a leader in this movement, promoting nondenominational church unions, federated churches, and community churches like his own. The church Burkhart built on this principle is today still a strong liberal church (even though long ago the Methodists posed a successful court challenge to the zoning ordinance that had given First Community a local monopoly).

But quite often the proponents of church mergers in the 1950s and 1960s found that their new union churches ended up no larger than each individual church that was absorbed into it.

They learned the hard way what later became a maxim of the church-growth movement: When it comes to church mergers, one plus one equals one. Then when the cultural storms of the 1960s arose, and mainline denominations showed signs of sinking, it was every denomination for itself. The church federation movement collapsed.

Each of these movements had its day. And for each, its day has now passed. Fifty years from now the same may well be said of Willow Creek.

How long will seeker services be popular? In what direction will cultural tastes in music, drama, and architecture change? What new ideas for evangelism and church life will arise and compete with those of Willow Creek? How long will other churches perceive the Willow Creek Association as a help to their ministries? How visionary and talented will Bill Hybels’ successors be? How long will the economy in the Chicago area thrive? What happens if Willow Creek’s neighbors change—if Starbucks, Lexus, the AMC cineplex, and Ikea move out and are replaced by Bob’s Package Liquor, Larry’s Auto Credit, South Barrington Adults Only, and Coach’s Rent-to-Own?

History seems to show that dynamic, growing churches require a combination of spiritual wisdom, cultural discernment, visionary leadership, talented management, favorable demographics, and adequate financial resources. Remove any of these and the church begins to fade. Bringing them all together is hard enough; keeping them together for a long time is nearly impossible.

And this is only looking at matters from a human point of view. If the Bible is right, it is ultimately God who decides which ministries will prosper in numbers and resources—though his reasons for allowing any ministry to prosper or struggle are known only to him. (Woe to anyone who presumes that the success of one’s ministry is a sign of God’s approval.)

In human economic reckoning, the institutional church movement, the gospel tabernacle movement, and the liberal community church movement are all accounted as having ultimately failed. But in God’s economy, they may have accomplished his exact purposes for exactly the right length of time. Perhaps this is what we need to hope and pray for the future of Willow Creek: that it remain faithful to what God calls it to do for whatever time he has allotted it.

Michael S. Hamilton is an assistant professor of history at Seattle Pacific University.

Related Elsewhere

Don’t’s miss Christianity Today‘s related articles “Community Is Their Middle Name” and “The Man Behind the Megachurch.”

Other articles about Willow Creek’s growth and influence include:

Willow Creek’s growth came by word-of-mouth, not advertising—The Baptist Standard (April 17, 2000)

Network’s management style puts an unlikely mix of congregations on the cutting edge—The Dallas Morning News (June 20, 1998)

Commonly Asked Questions About Willow Creek Community Church—The Atlantic Monthly

Previous Christianity Today articles about Willow Creek include:

Repentance or Propaganda? | At Willow Creek conference, President Clinton reviews his moral failures, details his spiritual recovery. (Aug. 11, 2000)

Willow Creek Church Readies for Megagrowth | New auditorium will seat 7,000. (May 5, 2000)

Willow Creek’s Methods Gain German Following | (April 26, 1999)

Hybels Does Hamburg | Will Willow Creek’s model float in Germany? (January 6, 1997)

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.