It seems network TV is high on Jesus this season. Maybe it’s the millennium, or just the hunger for ratings, but the Son of God has been the subject of major films on each of the Big Three networks. Mary, Mother of Jesus premiered in November on NBC to mostly lukewarm reviews; ABC broadcast a critically acclaimed claymation feature, The Miracle Maker, on Easter Sunday; and a four-hour Jesus miniseries airs this month on CBS (May 14 and 17 at 9 p.m. et). In addition, ABC journalist Peter Jennings has turned his personal fascination with Christ into a forthcoming prime-time news special, tentatively titled Peter Jennings: In Search of Jesus.

Jennings is not alone. Humankind has been seeking the Christ long before and ever since the Magi’s journey to Bethlehem. “We would see Jesus,” said the Greeks in their petition to meet the Christ (John 12:21). That thirst has long driven our souls, and it has shown up in both wonderful and tragic ways: for every sacred pilgrimage there is a holy war.

The fact is that, deep down, if we had our druthers, we all would “see Jesus,” even the blindest of us, for that connection with God is the intimacy for which we were made in the first place. We spend most of our lives longing for a glimpse, some intimate, palpable moment in which we know Light, and Light knows us.

We see this no place more clearly than in the tradition of high art in the West: the frescoes of Michelangelo, the oratorios of Bach and Handel, the allegories of Bunyan, Milton, and Tolkien, the poetry of Blake, Hopkins, and Eliot, ad mysterium. As diverse as they are, all of these attempt to encounter and interpret the divine.

And then there are the movies.

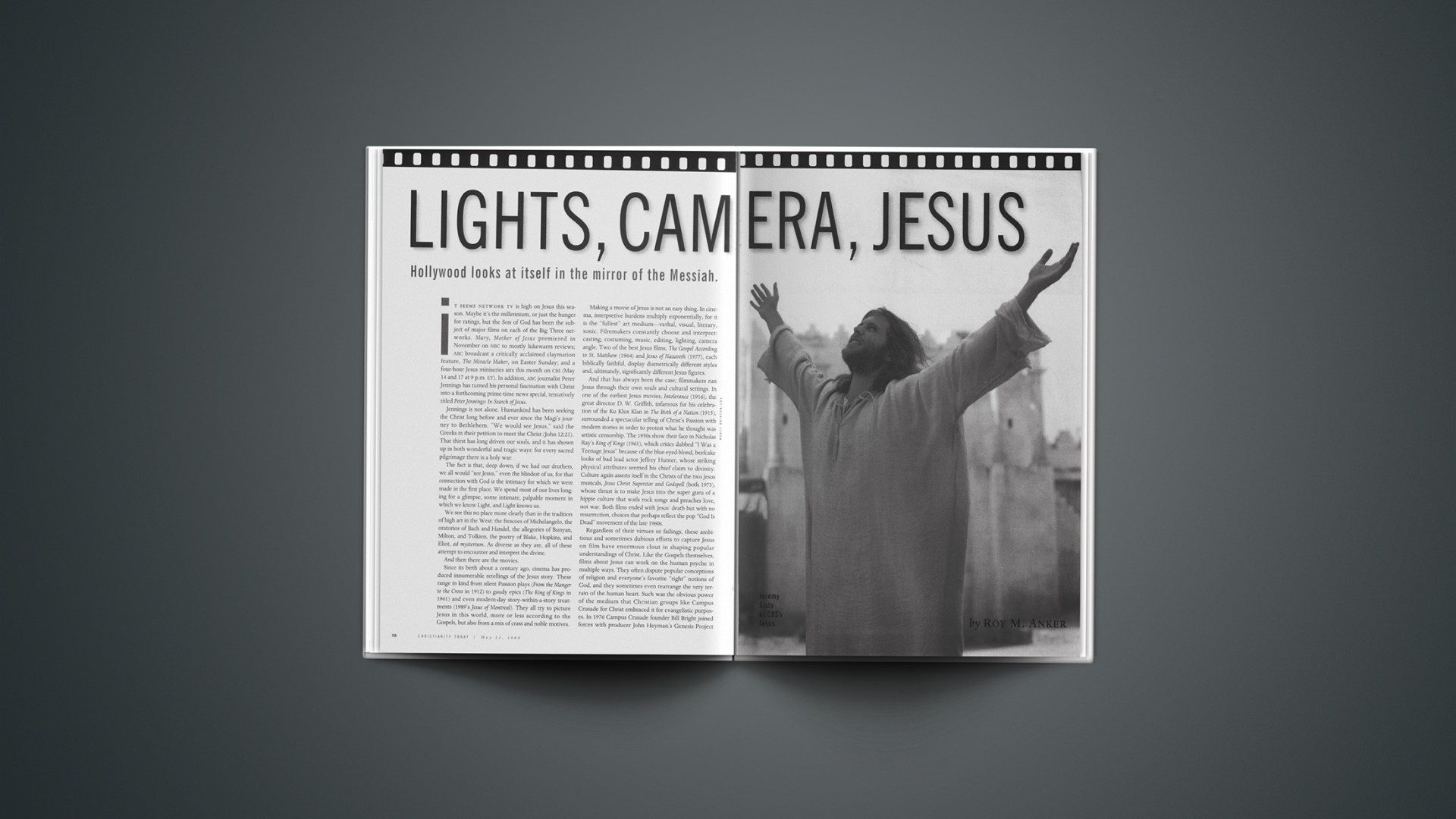

Since its birth about a century ago, cinema has produced innumerable retellings of the Jesus story. These range in kind from silent Passion plays (From the Manger to the Cross in 1912) to gaudy epics (The King of Kings in 1961) and even modern-day story-within-a-story treatments (1989’s Jesus of Montreal). They all try to picture Jesus in this world, more or less according to the Gospels, but also from a mix of crass and noble motives.

Making a movie of Jesus is not an easy thing. In cinema, interpretive burdens multiply exponentially, for it is the “fullest” art medium—verbal, visual, literary, sonic. Filmmakers constantly choose and interpret: casting, costuming, music, editing, lighting, camera angle. Two of the best Jesus films, The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) and Jesus of Nazareth (1977), each biblically faithful, display diametrically different styles and, ultimately, significantly different Jesus figures.

And that has always been the case; filmmakers run Jesus through their own souls and cultural settings. In one of the earliest Jesus movies, Intolerance (1916), the great director D. W. Griffith, infamous for his celebration of the Ku Klux Klan in The Birth of a Nation (1915), surrounded a spectacular telling of Christ’s Passion with modern stories in order to protest what he thought was artistic censorship. The 1950s show their face in Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961), which critics dubbed “I Was a Teenage Jesus” because of the blue-eyed-blond, beefcake looks of bad lead actor Jeffrey Hunter, whose striking physical attributes seemed his chief claim to divinity. Culture again asserts itself in the Christs of the two Jesus musicals, Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell (both 1973), whose thrust is to make Jesus into the super guru of a hippie culture that wails rock songs and preaches love, not war. Both films ended with Jesus’ death but with no resurrection, choices that perhaps reflect the pop “God Is Dead” movement of the late 1960s.

Regardless of their virtues or failings, these ambitious and sometimes dubious efforts to capture Jesus on film have enormous clout in shaping popular understandings of Christ. Like the Gospels themselves, films about Jesus can work on the human psyche in multiple ways. They often dispute popular conceptions of religion and everyone’s favorite “right” notions of God, and they sometimes even rearrange the very terrain of the human heart. Such was the obvious power of the medium that Christian groups like Campus Crusade for Christ embraced it for evangelistic purposes. In 1976 Campus Crusade founder Bill Bright joined forces with producer John Heyman’s Genesis Project to make Jesus (1979). Campus Crusade takes great pride in the film, claiming that it has reached an estimated 3 billion viewers in more than 550 languages and effected over 108 million “decisions for Christ.” Though other ministry-driven Jesus films have been produced, Jesus stands out as the most influential.

Ultimately, though, Hollywood has the deepest pockets when it comes to making movies, and clearly Jesus’ life is one of the greatest non-copyrighted sources of story material for studios and television networks looking for a hit. And if this TV season is any indication, mainstream filmmakers will continue to offer new views of Jesus—both who the Bible says he is and who they want him to be.

Telling the Greatest Story

The challenge is how to tell the “greatest story” freshly enough to keep viewers interested. That desire for freshness clearly stood out in the first movie epic devoted entirely to Jesus, Cecil B. De Mille’s silent classic The King of Kings (1927). Later in life, De Mille would produce such cinematic spectacles as The Ten Commandments (1956) and become the master of the Hollywood religious soap opera by playing freely with biblical history, melodramatizing plot, and sensationalizing characters toward the lubricious. His desire to grab audiences with whatever it takes is plain enough in his plot “innovations” in The King of Kings: Mary Magdalene becomes a wealthy and scantily clad courtesan in love with Judas Iscariot, who has attached himself to the political coattails of the popular miracle-worker, Jesus. Some of the most popular “Jesus films” have put Jesus himself at the periphery, like the hugely successful “bathrobe epics” The Robe (1953) and Ben-Hur (1959). In these works, Christ’s story is incidental, a mere backdrop for a larger and generally more romanticized first-century adventure.

One of the more compelling leads into the history of Jesus, Roberto Rossellini’s The Messiah (1978), a film never theatrically released in this country, starts far back in Israel’s longing first for a king and then for the Messiah. In contrast, Ray’s King of Kings, borrowing only the title from De Mille’s film, hauls in marital feuds, court intrigue, and Jewish rebel raids led by the zealot Barabbas. Occasionally even Jesus shows up.

The new Jesus miniseries on CBS continues the Zealots’ anti-Roman crusade, develops a hopeless “love story” between Jesus (before his baptism) and Lazarus’s sister Mary, and has Jesus clash vividly with a decidedly contemporary Satan. Not all of these story devices work to good effect [see “Desperately Seeking Jesus,” p. 62].

Unfortunately, in its adaptations of the Bible to the screen, Hollywood has often mistaken lavish sets, sweeping locales, soupy subplots, and splashy casting for reverence. For instance, George Stevens’s The Greatest Story Ever Told is based not directly on the Gospels but on Fulton Oursler’s romance novel about them. The film looks like earnest biblical scholarship, and one cannot fault Stevens, a devout Christian, for wanting to do full cinematic justice to the Gospels’ story. Still, pious intentions readily go awry.

While The Greatest Story largely dispenses with the melodrama of its immediate U.S. predecessor, Ray’s King of Kings, it manifests an outlandish faux solemnity that flattens the vitality of the story. Worse still is Stevens’s effort to add weight to the film by packing it with a pantheon of stars whose presence constantly distracts from the narrative, especially Charlton Heston (fresh from Ben-Hur) as John the Baptist and a drawling John Wayne as the centurion at the Crucifixion. Wayne’s “Truly, this man was the Son of God” line may be among the most unintentionally comical in Hollywood history. A young Max von Sydow plays Jesus aloofly, even icily, spouting King James English in a Swedish accent. His Jesus is so inoffensive that a fate like crucifixion seems unlikely.

The masterwork of Jesus pictures is Franco Zeffirelli’s six-hour television miniseries. Jesus of Nazareth premiered Palm Sunday, 1977, on NBC and immediately took its place as one of the most acclaimed Jesus films, especially in the evangelical community. In an editorial at the time, CT called the acting and cinematography superb and lauded the film for its fidelity to the Gospel accounts, adding that “the depiction of the resurrection is the best ever filmed.”

A celebrated Italian director, Zeffirelli had earlier done Romeo and Juliet (1968) and a colorful take on the life of Francis of Assisi, Brother Sun, Sister Moon (1973), and his embrace of the miniseries was an act of devotion. The film is certainly the most watchable of the Jesus pictures, for it is gorgeously shot, biblically accurate, and very often deeply moving. The re-creation of first-century Judaism is meticulous: Zeffirelli wonderfully details the Judaic texture of life in Nazareth, the flow of crowds around Jesus, and the physical spaces of the synagogue and the Temple.

Still, Jesus of Nazareth has drawn strident criticism, namely that it is too pretty, too Anglo, and too tame. Some of the criticisms are on the mark. Zeffirelli uses his medium with painterly precision, and Jesus of Nazareth is full of lovely production design. The question is whether all this artfulness clarifies or muddles the meaning of Jesus’ life. The same concern pertains to Anglicizing the story with very polished northern European actors (for example, Laurence Olivier as Nicodemus) speaking in Shakespearean prose. Religious film scholar Lloyd Baugh, in his fine book Imaging the Divine, claims the “basic problem” with Jesus of Nazareth is that to placate pop culture, Zeffirelli sacrificed “subtlety, moral complexity, and spiritual depth.”

Ultimately these complaints are overwhelmed by Zeffirelli’s obvious faithfulness to the heart of the gospel. Further, Baugh’s charge that this Jesus, played poignantly by Robert Powell, is not radical enough just does not fly. There is conflict, miracle, and messianic suffering, and there is no missing Jesus’ sense of his significance and divine destiny—a characteristic not always clear in other Jesus films, including CBS’s latest entry. Where the film creates fictional “filler” to clarify or move the story, it seems credible without bending toward melodrama. Zeffirelli clearly labored to strike the right balance between Jesus’ humanity and divinity. If Powell’s performance occasionally feels too “British,” the film’s overall effect more than compensates for the imbalance.

Testing Our Christology

Any retelling is interpretation, no matter how literal and faithful one strives to be. Ordinary human finitude, narrowness, and ego-need make getting the Good News straight a formidable task, even in the best of circumstances, especially with denominations and scholars disagreeing on what it all means. In films of Jesus, moviemakers run into this most directly in their selection of events for the narrative, and these in large measure dictate the portrait of Jesus: Is he mystic, rebel, healer, prophet, wisdom-teacher, lawbreaker, nature-lover, Mary’s boy, Messiah? Some critics contend that certain events make all the difference: the temptation, the Transfiguration, the Passion, the Resurrection. What does one need to really “see” Jesus?

The biggest controversy over Jesus films has been the reality and measure of Jesus’ humanity, and a question like this sorely tests a critical part of everyone’s theology. Even before its premiere, Jesus of Nazareth sparked controversy when Zeffirelli told the media that his film would emphasize Christ’s humanity. Fundamentalist Christian groups promptly waged a campaign against the miniseries that ultimately led to General Motors withdrawing as sole sponsor.

One of the more controversial debates in the history of Jesus pictures focuses on specific cinematic portrayals of the actual human person Jesus. Until perhaps the mid-’60s, cinematic portrayals of Jesus cast the Son of Man as decidedly bland or diffident, resolutely unexpressive. That problem, of course, pertains to the Gospels themselves. The Gospels show Jesus acting as God—teacher, preacher, healer, prophet—and save for a few celebrated instances we have little idea of what he felt like on the inside, as a human being, God-in-the-flesh.

Even in Jesus’ public life, when he is preaching or healing, we have little impression of his mood or demeanor, and different films variably portray his preaching style as fierce, constrained, playful, or exuberant. The personality is even more cryptic: cheerful or dour, warm or remote, serene or troubled, brawny or meek-and-mild? And there are bigger issues here than annoyance with empty portrayals of Jesus. The Jesus in some films raises the question of why people would follow him, let alone drop their livings and families to do so. What in Jesus occasions love for him other than his supply of miracles, which often play as the only validation and attraction of Jesus’ divinity? Ultimately, this spills into the larger apologetic question of what exactly makes any would-be Jesus or prophet the real thing.

Film has a way of testing our Christology. Orthodox Christian theologies claim that Jesus was both God and man. In addition to raising the dead, he laughed, cried, ate, possibly snored when he slept. Yet it’s hard for us to actually see this humanity—Jesus on the screen, walking, talking, being human. It’s easier to have a sure-fire miracle person who cannot fail to rescue us all.

The Controversial Christ

In 1964, more than 20 years before Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, a low-budget Italian film initiated the long-running debate about the extent and nature of Jesus’ humanity. Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew offered a fresh, non-extravaganza approach to the life of Jesus. The film was shot documentary-style in the stark, barren landscape of southern Italy, a place that makes Palestine look inviting and lush. Pasolini heightened the stringent quality of his setting by filling his cast with the unglamorous faces of poor local residents. All of this he filmed in high-contrast black and white. With this palette the film assumes a somber earnestness. These choices jell with the Jesus he depicts (played by Enrique Irazoqui), whose demeanor is usually fierce, if not angry, and who seems entirely humorless. The text itself is taken entirely from Matthew, although Pasolini elides small slivers. With a neorealist camera and rapid, aggressive editing, this is a very literal Jesus whose radicalness is not in the least diluted.

Though markedly different from the religious epics of the ’50s and ’60s, St. Matthew was well received in its day. No doubt adding some sensation to the reception of the film was Pasolini’s being a prominent Italian intellectual and avowed Marxist who did not believe in God. He was, however, fascinated by the radical character of Jesus. Critics have suggested that Pasolini shades his telling to further intensify the already sizable conflict between Jesus and the Jewish establishment. What results is a spare, stringent, and haunting story, one that is remarkably faithful, incisive, and discomforting. This Jesus is hard to take, and that perhaps is as it should be. The film is so very compelling that viewers wonder if the atheist Marxist didn’t get it exactly right.

Before long, other films came along that explored Jesus’ life in increasingly unconventional and even irreverent ways. These so-called “scandal films” departed from traditional versions of the Gospel stories to explore specific elements of Christ’s character and the effect of religion within society. There is Monty Python’s broad-brushed satire Life of Brian (1979) and the two Jesus musicals among others. Many of these movies ignited charges of blasphemy from conservative religious leaders who were angered by the films’ supposed sacrilege.

The most controversial of all Jesus pictures, of course, is Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), which was loosely based on Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis’s 1955 fictional exploration of the divinity of Christ. Kazantzakis did not so much question the divinity of Jesus as construct a story that tried, first, to depict what it might have been like for God to live in humanity and, second, to fathom the measure of Jesus’ sacrifice. An earnest Catholic, Scorsese appreciated the novel because it presented a more human Jesus who understood humanity from the inside out. The same was true for screenwriter Paul Schrader, a graduate of Calvin College. Early leaked versions of the screenplay provoked huge protests from the conservative Christian community, and the very different released film continued to draw fervent protests.

All of that was too bad, for The Last Temptation was a serious inquiry into what it was like for Jesus the man to also be God, and into the measure of sacrifice demanded of Jesus. Schrader defended the release of the movie in a 1988 interview with CT. “All I was trying to do was provoke discussion about Christ,” he said. “[W]hen I was at Calvin College, we were encouraged to discuss views of Christ that didn’t necessarily match our own. …This movie may err on the side of Christ’s humanity, but it certainly doesn’t make up for centuries in which Christ’s humanity has been glossed over in art and literature.”

The truth is, parts of The Last Temptation work extremely well. It does a splendid job of re-creating the texture of life in first-century Palestine, and there are stunning visual sequences, such as Jesus in the wilderness. The film was not helped by some bad casting choices, especially Willem Dafoe as Jesus.

The controversy over the movie focused primarily on two issues: the character of Jesus and the assertion that Jesus committed sexual sin. The first of these carries the most weight, for Scorsese’s Jesus is a man as much tortured as loved by God. His calling to be God is not a welcome one, and Jesus never seems to fully embrace it. To some extent Schrader and Scorsese do overcorrect the historic neglect of the humanity of Jesus by a church that has generally preferred a magisterial, God-sure Savior. Scorsese significantly overstates Jesus’ struggles, making him uncertain and self-abusive, much like characters in his earlier films, including Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980). There is never any doubt that Jesus is God, but Scorsese so wanted a Christ with whom frail humanity might identify that his Jesus appears troubled to the point of neurosis.

The other protest indicted The Last Temptation for presenting Jesus as guilty of sexual trespass. But this does not happen in the movie. Yes, Jesus is tempted on the Cross (through a vivid dream sequence) to leave it to enjoy the glories of ordinary life—marriage, children, friends, and long life—but that is clearly specified as a temptation, the last temptation, pitched to him at his most vulnerable moment. It is seductive and powerful, which is the nature of temptation. In the end, Jesus emphatically rejects these blandishments of the devil (here coming as a young winsome girl) to embrace the sacrifice that is the Cross. This trenchant sequence captures the very nature of temptation while clarifying and deepening the measure of Jesus’ sacrifice.

Light On the Screen

Scorsese’s movie, though an extreme example, raises a compelling question about Jesus films in general. Can any treatment of Jesus’ story really convey a fair, helpful, or faithful presentation of God in the flesh—or hint at the mystery and miracle of the Incarnation? Or will Hollywood forever see its own ideologies, weaknesses, and yearnings in the cinematic Christ?

Film stock catches light to tell its story. It is, however, far harder to put Light itself on the screen. In the movies, as in life, we have a hard time seeing Jesus. The great help of these many portraits in the Jesus pictures is that they challenge us to test the accuracy of what we really know of Jesus, specifically whether our understanding comes from Scripture or pop culture. And, better yet, Jesus movies can often stretch the soul to know and see Christ, as if for the first time.

In this busy TV season of Jesus movies, it’s clear that the genre is very much alive. Though cinematic approaches have changed through the years, filmmakers continue a quest that goes far beyond the pursuit of higher ratings and bigger box-office receipts (though that’s certainly a part of it). This quest is about seeing and hearing—knowing—a first-century Rabbi whose deeds and words still jar us. It’s about glimpsing just a bit of what Emmanuel—God with us—might look like. Jesus movies will continue as long as Hollywood has cameras and people thirst in their souls.

Roy M. Anker is a professor of English at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and the coeditor of Perspectives: A Journal of Reformed Thought.

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.