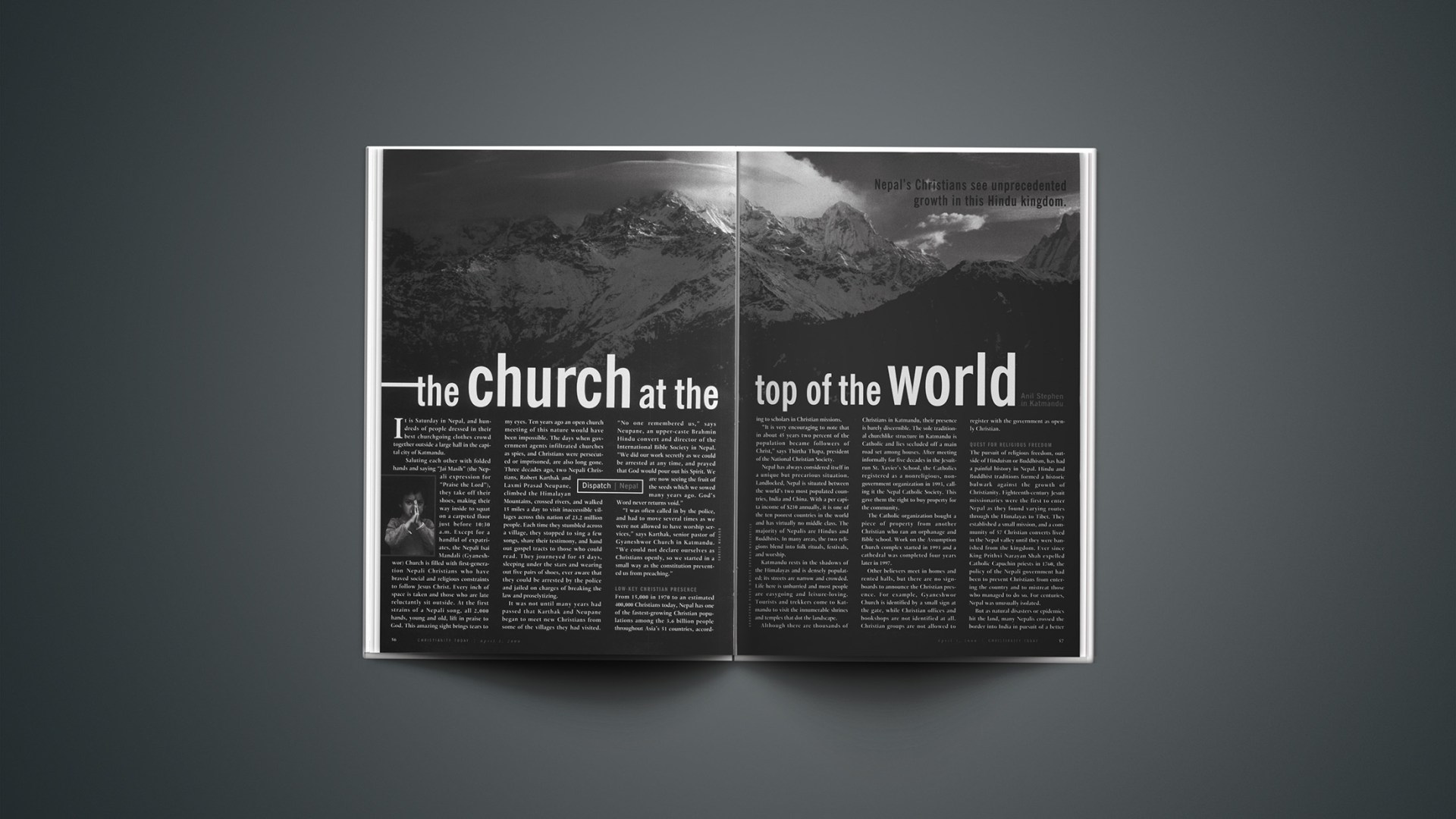

It is Saturday in Nepal, and hundreds of people dressed in their best churchgoing clothes crowd together outside a large hall in the capital city of Katmandu.

Saluting each other with folded hands and saying “Jai Masih” (the Nepali expression for “Praise the Lord”), they take off their shoes, making their way inside to squat on a carpeted floor just before 10:30 a.m. Except for a handful of expatriates, the Nepali Isai Mandali (Gyaneshwor) Church is filled with first-generation Nepali Christians who have braved social and religious constraints to follow Jesus Christ. Every inch of space is taken and those who are late reluctantly sit outside. At the first strains of a Nepali song, all 2,000 hands, young and old, lift in praise to God. This amazing sight brings tears to my eyes. Ten years ago an open church meeting of this nature would have been impossible. The days when government agents infiltrated churches as spies, and Christians were persecuted or imprisoned, are also long gone. Three decades ago, two Nepali Christians, Robert Karthak and Laxmi Prasad Neupane, climbed the Himalayan Mountains, crossed rivers, and walked 15 miles a day to visit inaccessible villages across this nation of 23.2 million people. Each time they stumbled across a village, they stopped to sing a few songs, share their testimony, and hand out gospel tracts to those who could read. They journeyed for 45 days, sleeping under the stars and wearing out five pairs of shoes, ever aware that they could be arrested by the police and jailed on charges of breaking the law and proselytizing.

It was not until many years had passed that Karthak and Neupane began to meet new Christians from some of the villages they had visited. “No one remembered us,” says Neupane, an upper-caste Brahmin Hindu convert and director of the Inter national Bible Society in Nepal. “We did our work secretly as we could be arrested at any time, and prayed that God would pour out his Spirit. We are now seeing the fruit of the seeds which we sowed many years ago. God’s Word never returns void.”

“I was often called in by the police, and had to move several times as we were not allowed to have worship services,” says Karthak, senior pastor of Gyaneshwor Church in Katmandu. “We could not declare ourselves as Christians openly, so we started in a small way as the constitution prevented us from preaching.”

LOW-KEY CHRISTIAN PRESENCE

From 15,000 in 1970 to an estimated 400,000 Christians today, Nepal has one of the fastest-growing Christian populations among the 3.6 billion people throughout Asia’s 51 countries, according to scholars in Christian missions.

“It is very encouraging to note that in about 45 years two percent of the population became followers of Christ,” says Thirtha Thapa, president of the National Christian Society.

Nepal has always considered itself in a unique but precarious situation. Land locked, Nepal is situated between the world’s two most populated countries, India and China. With a per capita income of $210 annually, it is one of the ten poorest countries in the world and has virtually no middle class. The majority of Nepalis are Hindus and Buddhists. In many areas, the two religions blend into folk rituals, festivals, and worship.

Katmandu rests in the shadows of the Himalayas and is densely populated; its streets are narrow and crowded. Life here is unhurried and most people are easygoing and leisure-loving. Tourists and trekkers come to Kat mandu to visit the innumerable shrines and temples that dot the landscape.

Although there are thousands of Christians in Katmandu, their presence is barely discernible. The sole traditional churchlike structure in Katmandu is Catholic and lies secluded off a main road set among houses. After meeting informally for five decades in the Jesuit-run St. Xavier’s School, the Catholics registered as a nonreligious, nongovernment organization in 1993, calling it the Nepal Catholic Society. This gave them the right to buy property for the community.

The Catholic organization bought a piece of property from another Christian who ran an orphanage and Bible school. Work on the Assumption Church complex started in 1993 and a cathedral was completed four years later in 1997.

Other believers meet in homes and rented halls, but there are no signboards to announce the Christian presence. For example, Gyaneshwor Church is identified by a small sign at the gate, while Christian offices and bookshops are not identified at all. Christian groups are not allowed to register with the government as openly Christian.

QUEST FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

The pursuit of religious freedom, outside of Hinduism or Buddhism, has had a painful history in Nepal. Hindu and Buddhist traditions formed a historic bulwark against the growth of Christianity. Eighteenth-century Jesuit missionaries were the first to enter Nepal as they found varying routes through the Himalayas to Tibet. They established a small mission, and a community of 57 Christian converts lived in the Nepal valley until they were banished from the kingdom. Ever since King Prithvi Narayan Shah expelled Catholic Capuchin priests in 1760, the policy of the Nepali government had been to prevent Christians from entering the country and to mistreat those who managed to do so. For centuries, Nepal was unusually isolated.

But as natural disasters or epidemics hit the land, many Nepalis crossed the border into India in pursuit of a better life. Some were drawn into India’s Christian enclaves, beginning a vibrant ethnic Nepali church within India.

William Carey, the legendary British missionary who spent a lifetime in India, was the first to recognize the need for a Nepali Bible. He started translating the New Testament in 1812 in Serampore, India, completing the New Testament in 1821. Ganga Prasad Pradhan, a Nepali pastor, translated the entire Bible into Nepali in 1914. Until Nepalis published Bibles within the country, they imported Bibles from India—but those were often seized by customs officials. Today, the New Testament has been translated into colloquial Nepali and 10,000 copies of the Gospel of Mark designed especially for children have been distributed in recent months.

The year 1990 is often referred to as a defining moment in Nepal’s history, when democracy and religious freedom gained new ground. Since 1961, King Mahendra had exercised autocratic control of the country—in part by banning political parties and introducing Panchayat, a traditional Hindu form of local governing councils.

Under Panchayat, Christians (as well as other distrusted groups) were persecuted and at least 300 pastors and Christians were jailed. Many Christians suffered police brutality, and at least one died because of it. Through this difficult time, the church was driven underground and Nepali Christians practiced secret lives of prayer.

As repressions grew more commonplace, resistance to the monarchy gained strength. In 1990, pent-up demands for reform triggered civil unrest on a massive scale. Eventually, the Nepali Congress Party gained majority control of the new parliament, leading to many other democratic reforms and setting the stage for a significant growth of Christianity in Nepal.

The primary responsibility of taking the gospel to the people has rested on the Nepali church from the very beginning.

Women played a key role in establishing the church in Nepal and continue to do so. Two women, Gyani Shah (an early Nepali convert) and Elizabeth Franklin (a missionary with Regions Beyond Missionary Union), were instrumental in establishing two of the oldest churches in Katmandu: Putali Sadak Church and Nepali Isai Mandali (Gyaneshwor) Church.

Their example has multiplied many times during the last 50 years.

Since most Nepali congregations are the result of work by Nepalis themselves, Christians from Nepal are evangelists at heart. Nepali Christians—many of whom are illiterate—share the gospel frequently and informally, sometimes over a cup of hot tea. Crusade-style evangelism is unknown to them.

Silas Bogati, a Catholic deacon in Katmandu preparing to enter the priesthood in August, says he became a Christian after a man gave him a gospel tract. “I was born and raised as a Hindu till I was 19. The Christian message of love really appealed to me when a man on the street shared with me John 3:16. Then I started attending Bible courses and became a Christian.”

The zeal of Christians has been infectious. Nepali Christians attribute church growth to miracles, prayers, and Jesus’ continuing acts of healing and deliverance. Nepali Christians say their neighbors often call them to pray because sick people are healed and the demon-possessed are set free. Gopaljee Adhikari of the Lord’s Church recounts a miracle in his congregation: “A man brought his brother who was paralyzed. We prayed for him, and two weeks later he was healed and came on his own to church.”

Miracles are a powerful testimony to the community. “At least 40 to 60 percent of the Nepali church became Christians as a direct result of a miracle,” says Sandy Anderson of the Sowers Ministry. “Most times the people do not know what we are talking about when we preach the gospel. That’s why it is very important to demonstrate the gospel. We preach. Then God heals the sick when we pray. The gospel is not only preached but demonstrated in Nepal.”

CHANGING RELIGION, NOT CULTURE

Even though Nepal is a parliamentary monarchy and democratic reforms are in place, the old feudal caste system remains influential.

The Nepalis are highly religious and consider Hinduism their cultural wellspring. Nepali Hindus see Christianity as a foreign, cow-eating religion. (In Hinduism, the cow is revered as a god.) Public criticism of Christianity is accepted and vitriolic. For the past year, Nepal’s mass media have launched an extensive campaign against Christians, accusing them of destroying the Nepalese culture.

A Nepali Hindu who becomes a Christian “breaks caste”—an action that has dramatic personal, family, and social consequences. Chirendra Satyal’s grandfather was a Brahmin priest to rulers of the country. “When I became a Christian, I tried to tell people that I was only changing my religion and not my culture,” says Satyal, now an active Catholic journalist. “But they were skeptical.” The media also describe believers as terrorists or illegal residents. Most Christians tend to ignore such accusations. “[The media] are putting psychological pressure on us,” says Adhikari. “We just have to pray and face the situation.”

To counter the criticism, the people of Siabru, near Helembu Mountain, decided to express their faith in sync with their culture. Historically Buddhist, they once followed the age-old custom of flying Buddhist prayer flags around their village for protection from evil. When they became Christians, they decided to maintain their culture and style of worship and still follow the traditional Buddhist style of singing, but substituted Christian words. They also kept the prayer flags but instead of having Buddhist scriptures they inscribed Bible verses.

As more foreigners visit Nepal, more Christian groups, mostly Protestant and from the wealthy West, are trying to initiate ministry within the country.

“Nepal has become a mission tourist center,” says Narayan Sharma of Gospel for Asia. But some Protestant groups have maintained a successful presence in the country for decades. TEAM, an interdenominational agency, dates its presence in Nepal to 1892. Today, more than a dozen American mission groups have more than 100 personnel in Nepal. In most cases, the Nepali government requires outside agencies to agree not to proselytize.

“If you want to help the church in Nepal, don’t just pour in money,” Anderson says. “Build relationships before you support anyone. Give money and resources to men and women of credibility.”

According to Nepali church leaders, a troubling offshoot of the growth in missions spending is that a few Nepali church leaders live “like millionaires and drive fancy cars.” Local leaders say giving money to individuals rather than to church groups has done much harm and brought disgrace to Christians.

“We have tried to talk to our friends and yet they get their support from outside,” Karthak says ruefully. “I tried to help some of the church leaders by asking them why they don’t teach their people to give to the Lord’s work.” Karthak himself has taken a cautious approach and is not dependent on outside funding.

Despite differences over money or doctrine, Nepali Christians find that their status as a religious minority gives a strong incentive to stick together because discrimination and official harassment still take place. According to Thapa of the National Christian Society, Christians experience discrimination within their families.

“I came from a strong Hindu family and belonged to the Kshatriyas, the second-highest caste family in Nepal,” says Bogati. “When I went back to my village after I became a Christian, one of my uncles would not allow me into the house. I had become an untouchable.”

Additional discrimination takes place within the community. Neighbors consider a change in religion as tantamount to deserting the community and showing contempt for their culture. Peter, a worker with the International Bible Society, and his family were banished from their village when he refused to follow Hindu traditions at his father’s death.

The third level of discrimination is subtle but legal, having a chilling effect on Christian outreach. Christian organizations are not allowed to register as religious entities, giving them no official legal standing. “Even though people are aware of us, the government does not want to register us,” Neupane says. “They ask us to change our names and remove any association with the Bible, but we do not want to lose our identity.”

A HOME, NOT A HOTEL

A common accusation made against churches in Nepal is that Christians are converting the poor by offering financial inducement.

Yet every Saturday at church services, a few more Nepalis make a commitment to Christianity. No one is called to the front to make a public declaration of faith. Instead, converts sign a document affirming that their choice is of their own free will. Christian leaders do not see false charges of financial enticement as a central worry about church growth. They are more inclined to see the fate of new Christians in biblical terms, akin to Jesus’ parable of seeds that grow but are choked by worldly cares and concerns.

“Our approach has been lopsided,” Karthak admits, saying an emphasis on outreach is sometimes out of balance with teaching Christian doctrine to new disciples. “Our churches are like transit camps. We don’t want people to treat the church like a hotel, but a home.”

But Adhikari, while noting the drop out problem, adds: “Not more than 10 percent leave the church. In Nepal, those who make a decision to follow Christ are genuine, and they stick to their newfound faith.” Christians are encouraged to join small groups after their baptism. Nearly 300 such fellowships have mushroomed in Katmandu. But over the years, those fellowships have led to denominational association (which was unknown before 1990) and, in a few cases, splintered congregations.

Such fragmentation has at times cooled religious commitments. “We are neither hot nor cold but lukewarm Christians,” Karthak says. Gospel for Asia’s Sharma is blunt: “We need faithful people. I believe that healings will continue only if there is holiness and godliness in the church.”

After suffering for years, the church in Nepal has found strength in spite of persecution. Now that overt religious persecution has declined, Christians in Nepal are reassessing their purpose and overall mission. One enduring realization is that Christians in Nepal remain vulnerable. There were several incidents of official harassment in 1999. If Nepali law is strictly enforced, severe restrictions on Christians could again be in effect. Faced with this dilemma, Nepali Christians ask themselves: Does the church in Nepal fear persecution in the future? It is a question that many do not want to consider.

“I feel there will be persecution, but there are people within Nepali society who believe in human rights and will stand up for us,” Satyal says.

Another church leader says he is not worried. He just reprises Saint Paul’s words: “I am not ashamed of the gospel, because it is the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes: first the Jew, then also the Gentile and the Nepali Christian.”

In 1986, Gyani Shah challenged Nepali men and women never to be proud while serving the Lord, for pride causes loss of opportunity. The church in Nepal now heeds that advice as it prepares for the twenty-first century. In this newfound freedom, churches are springing up all over the country representing most ethnic groups and castes in this movement to Christ.

The Nepali church is no longer solely focused on itself, but is starting churches in Dubai, India, and other Asian countries. It is a big step of faith.

Nepali missions leaders say their goal is to “remain faceless” to be of use to Christians throughout Asia. That unusual quality is something Nepali Christians possess in abundance.

Related Elsewhere

For more on Nepal, see Britannica.com, Info-Nepal, and the Library of Congress.

Nepali Around the World: Emphasizing Nepali Christians of the Himalayas (Ekta Books, 1997) is a very hard to find book. But for those truly interested in the subject, Cindy L. Perry’s book is apparently the only major work on the subject. A review is available at the Web site of Studies in Nepali History and Society (SINHAS).

Adherents.com offers statistics on religion in Nepal.

CBN aired a report in 1998 on Christianity in Nepal.

The Nepal Bible Society offers a few statistics and information about the organization and country.

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.