In the 1997 movie Devil’s Advocate, the devil heads a major law firm. The devil’s protegé is a young attorney groomed to be “The One.” Al Pacino and Keanu Reeves are fantastic. The dialogue is gripping. The special effects are spellbinding. The premise is, by Hollywood standards, quite creative. But there is one huge problem.At the movie’s climax, there is a clash in the devil’s penthouse suite. As the devil stands before a larger-than-life sculpture of naked men and women who seem caught in a whirlpool of carved marble, the figures begin to move; soon they are coupling in orgiastic frenzy. The problem is, the art resembles a sculpture depicting God’s creation that graces the entrance of National Cathedral in Washington. When the artist of the Creation piece learns of the movie, he is enraged beyond words. Like David battling Goliath, the artist engages several law firms and threatens to sue the Warner Brothers division of the media giant Time Warner. Against all odds, the sculptor wins.Although his was hardly a household name, sculptor Frederick Hart has been compared to the French sculptor Rodin. Some people hailed him as America’s most popular contemporary sculptor. Ronald Reagan gave him a Presidential Design Excellence Award; President Bush commemorated his National Cathedral sculptures; and Pope John Paul II called one of Hart’s processional crosses “a profound theological statement.” Hart died tragically and unexpectedly at age 55 last August.He received an honorary doctorate from the University of South Carolina for his “ability to create art that uplifts the human spirit, [his] commitment to the ideal that art must renew its moral authority, [his] skill, and his contributions to the rich cultural heritage of our nation.” And although he suffered the rigors of poverty as a young artist, his pioneering work and marketing savvy in the field of acrylic sculpture made him a multimillionaire by his fifth decade. Hart’s untimely death leaves a tremendous gap in the small company of Christians making a difference in the world of high art. His example and his works remain enduring testimonies to the legacy a person of integrity can build through persistence.

THE ART WORLD’S OUTSIDER

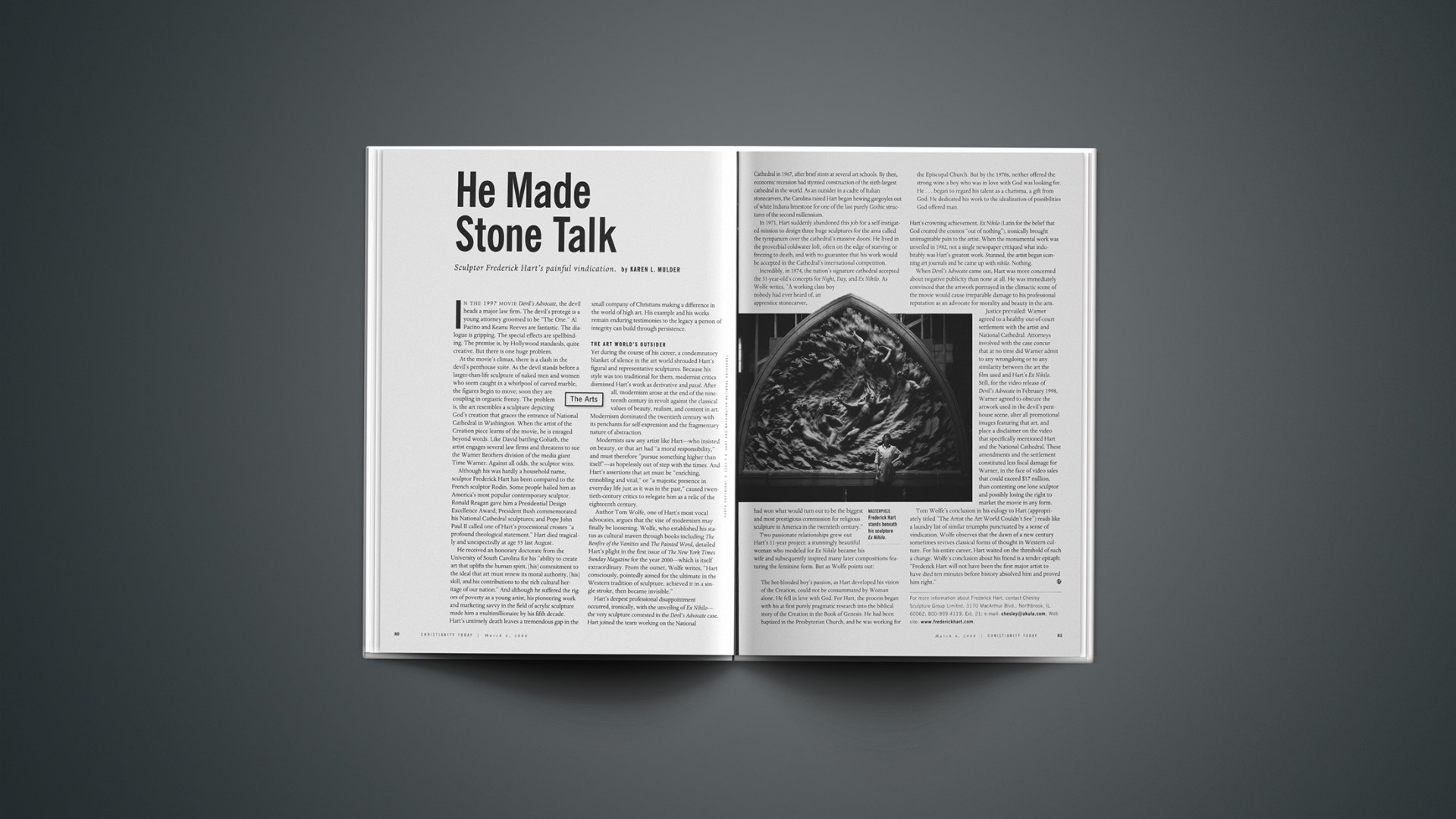

Yet during the course of his career, a condemnatory blanket of silence in the art world shrouded Hart’s figural and representative sculptures. Because his style was too traditional for them, modernist critics dismissed Hart’s work as derivative and passé. After all, modernism arose at the end of the nineteenth century in revolt against the classical values of beauty, realism, and content in art. Modernism dominated the twentieth century with its penchants for self-expression and the fragmentary nature of abstraction.Modernists saw any artist like Hart—who insisted on beauty, or that art had “a moral responsibility,” and must therefore “pursue something higher than itself”—as hopelessly out of step with the times. And Hart’s assertions that art must be “enriching, ennobling and vital,” or “a majestic presence in everyday life just as it was in the past,” caused twentieth-century critics to relegate him as a relic of the eighteenth century.Author Tom Wolfe, one of Hart’s most vocal advocates, argues that the vise of modernism may finally be loosening. Wolfe, who established his status as cultural maven through books including The Bonfire of the Vanities and The Painted Word, detailed Hart’s plight in the first issue of The New York Times Sunday Magazine for the year 2000—which is itself extraordinary. From the outset, Wolfe writes, “Hart consciously, pointedly aimed for the ultimate in the Western tradition of sculpture, achieved it in a single stroke, then became invisible.”Hart’s deepest professional disappointment occurred, ironically, with the unveiling of Ex Nihilo—the very sculpture contested in the Devil’s Advocate case. Hart joined the team working on the National Cathedral in 1967, after brief stints at several art schools. By then, economic recession had stymied construction of the sixth-largest cathedral in the world. As an outsider in a cadre of Italian stonecarvers, the Carolina-raised Hart began hewing gargoyles out of white Indiana limestone for one of the last purely Gothic structures of the second millennium.In 1971, Hart suddenly abandoned this job for a self-instigated mission to design three huge sculptures for the area called the tympanum over the cathedral’s massive doors. He lived in the proverbial coldwater loft, often on the edge of starving or freezing to death, and with no guarantee that his work would be accepted in the Cathedral’s international competition.Incredibly, in 1974, the nation’s signature cathedral accepted the 31-year-old’s concepts for Night, Day, and Ex Nihilo. As Wolfe writes, “A working class boy nobody had ever heard of, an apprentice stonecarver, had won what would turn out to be the biggest and most prestigious commission for religious sculpture in America in the twentieth century.”Two passionate relationships grew out Hart’s 11-year project: a stunningly beautiful woman who modeled for Ex Nihilo became his wife and subsequently inspired many later compositions featuring the feminine form. But as Wolfe points out:

The hot-blooded boy’s passion, as Hart developed his vision of the Creation, could not be consummated by Woman alone. He fell in love with God. For Hart, the process began with his at first purely pragmatic research into the biblical story of the Creation in the Book of Genesis. He had been baptized in the Presbyterian Church, and he was working for the Episcopal Church. But by the 1970s, neither offered the strong wine a boy who was in love with God was looking for. He became a Roman Catholic and began to regard his talent as a charisma, a gift from God. He dedicated his work to the idealization of possibilities God offered man.

Hart’s crowning achievement, Ex Nihilo (Latin for the belief that God created the cosmos “out of nothing”), ironically brought unimaginable pain to the artist. When the monumental work was unveiled in 1982, not a single newspaper critiqued what indubitably was Hart’s greatest work. Stunned, the artist began scanning art journals and he came up with nihilo. Nothing.When Devil’s Advocate came out, Hart was more concerned about negative publicity than none at all. He was immediately convinced that the artwork portrayed in the climactic scene of the movie would cause irreparable damage to his professional reputation as an advocate for morality and beauty in the arts.Justice prevailed: Warner agreed to a healthy out-of-court settlement with the artist and National Cathedral. Attorneys involved with the case concur that at no time did Warner admit to any wrongdoing or to any similarity between the art the film used and Hart’s Ex Nihilo. Still, for the video release of Devil’s Advocate in February 1998, Warner agreed to obscure the artwork used in the devil’s penthouse scene, alter all promotional images featuring that art, and place a disclaimer on the video that specifically mentioned Hart and the National Cathedral. These amendments and the settlement constituted less fiscal damage for Warner, in the face of video sales that could exceed $17 million, than contesting one lone sculptor and possibly losing the right to market the movie in any form.Tom Wolfe’s conclusion in his eulogy to Hart (appropriately titled “The Artist the Art World Couldn’t See”) reads like a laundry list of similar triumphs punctuated by a sense of vindication. Wolfe observes that the dawn of a new century sometimes revives classical forms of thought in Western culture. For his entire career, Hart waited on the threshold of such a change. Wolfe’s conclusion about his friend is a tender epitaph: “Frederick Hart will not have been the first major artist to have died ten minutes before history absolved him and proved him right.”For more information about Frederick Hart, contact Chesley Sculpture Group Limited, 3170 MacArthur Blvd., Northbrook, IL 60062; 800-999-4119, Ext. 21; e-mail: chesley@akula.com; Web site: www.frederickhart.com.

Related Elsewhere

Tom Wolfe’s New York Times Sunday Magazine article about Hart, “The Artist the Art World Couldn’t See,” is free online.In addition to Frederick Hart’s main site, FrederickHart.com, other Hart pages are at Artcyclopedia, the AJ Fine Arts, Ltd. Gallery, the Objets d’Art Gallery, Lahaina Galleries, Larry Smith Fine Art, New York Museums, and The Palm Beach Times, among other sites.Noah Adams of National Public Radio’s All Things Consideredinterviewed Hart in May 1998 and reflected on the sculptor upon his death last August.Frederick Hart: Sculptor is available at Amazon.com and other book retailers.

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.