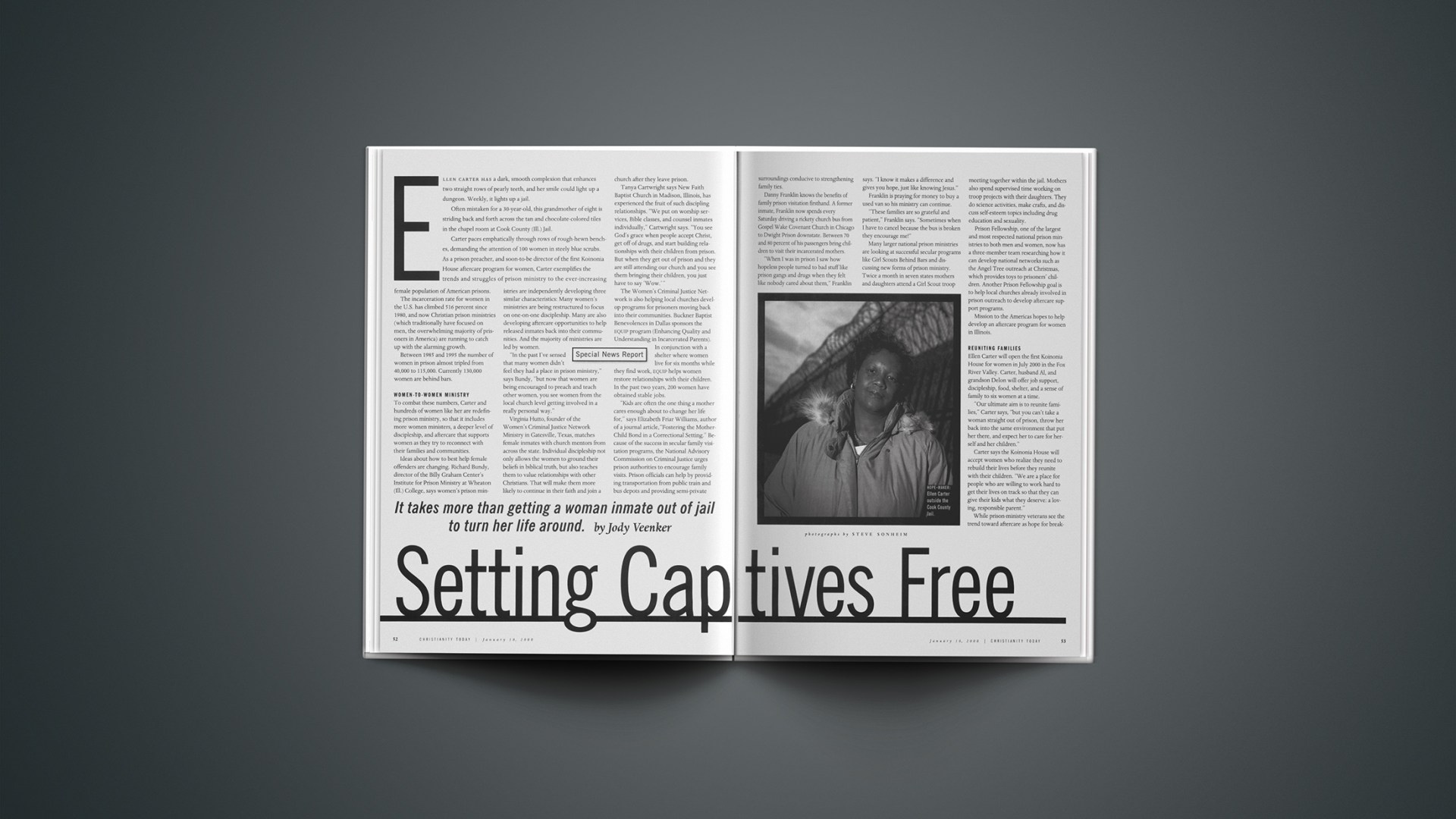

Ellen Carter has a dark, smooth complexion that enhances two straight rows of pearly teeth, and her smile could light up a dungeon. Weekly, it lights up a jail.Often mistaken for a 30-year-old, this grandmother of eight is striding back and forth across the tan and chocolate-colored tiles in the chapel room at Cook County (Ill.) Jail.Carter paces emphatically through rows of rough-hewn benches, demanding the attention of 100 women in steely blue scrubs. As a prison preacher, and soon-to-be director of the first Koinonia House aftercare program for women, Carter exemplifies the trends and struggles of prison ministry to the ever-increasing female population of American prisons.The incarceration rate for women in the U.S. has climbed 516 percent since 1980, and now Christian prison ministries (which traditionally have focused on men, the overwhelming majority of prisoners in America) are running to catch up with the alarming growth. Between 1985 and 1995 the number of women in prison almost tripled from 40,000 to 115,000. Currently 130,000 women are behind bars.

Women-To-Women Ministry

To combat these numbers, Carter and hundreds of women like her are redefining prison ministry, so that it includes more women ministers, a deeper level of discipleship, and aftercare that supports women as they try to reconnect with their families and communities.Ideas about how to best help female offenders are changing. Richard Bundy, director of the Billy Graham Center's Institute for Prison Ministry at Wheaton (Ill.) College, says women's prison ministries are independently developing three similar characteristics: Many women's ministries are being restructured to focus on one-on-one discipleship. Many are also developing aftercare opportunities to help released inmates back into their communities. And the majority of ministries are led by women."In the past I've sensed that many women didn't feel they had a place in prison ministry," says Bundy, "but now that women are being encouraged to preach and teach other women, you see women from the local church level getting involved in a really personal way."Virginia Hutto, founder of the Women's Criminal Justice Network Ministry in Gatesville, Texas, matches female in mates with church mentors from across the state. Individual discipleship not only allows the women to ground their beliefs in biblical truth, but also teaches them to value relationships with other Christians. That will make them more likely to continue in their faith and join a church after they leave prison.Tanya Cartwright says New Faith Baptist Church in Madison, Illinois, has experienced the fruit of such discipling relationships. "We put on worship services, Bible classes, and counsel inmates individually," Cartwright says. "You see God's grace when people accept Christ, get off of drugs, and start building relationships with their children from prison. But when they get out of prison and they are still attending our church and you see them bringing their children, you just have to say 'Wow.'"The Women's Criminal Justice Net work is also helping local churches develop programs for prisoners moving back into their communities. Buckner Baptist Benevolences in Dallas sponsors the equip program (Enhancing Quality and Understanding in Incarcerated Parents). In conjunction with a shelter where women live for six months while they find work, equip helps women restore relationships with their children. In the past two years, 200 women have obtained stable jobs."Kids are often the one thing a mother cares enough about to change her life for," says Elizabeth Friar Williams, author of a journal article, "Fostering the Mother-Child Bond in a Correctional Setting." Be cause of the success in secular family visitation programs, the National Advisory Com mission on Criminal Justice urges prison authorities to encourage family visits. Prison officials can help by providing transportation from public train and bus depots and providing semi-private surroundings conducive to strengthening family ties.Danny Franklin knows the benefits of family prison visitation firsthand. A former inmate, Franklin now spends every Saturday driving a rickety church bus from Gospel Wake Covenant Church in Chicago to Dwight Prison downstate. Between 70 and 80 percent of his passengers bring children to visit their incarcerated mothers."When I was in prison I saw how hopeless people turned to bad stuff like prison gangs and drugs when they felt like nobody cared about them," Franklin says. "I know it makes a difference and gives you hope, just like knowing Jesus."Franklin is praying for money to buy a used van so his ministry can continue."These families are so grateful and patient," Franklin says. "Sometimes when I have to cancel because the bus is broken they encourage me!"Many larger national prison ministries are looking at successful secular programs like Girl Scouts Behind Bars and discussing new forms of prison ministry. Twice a month in seven states mothers and daughters attend a Girl Scout troop meeting together within the jail. Mothers also spend supervised time working on troop projects with their daughters. They do science activities, make crafts, and discuss self-esteem topics including drug education and sexuality.Prison Fellowship, one of the largest and most respected national prison ministries to both men and women, now has a three-member team researching how it can develop national networks such as the Angel Tree outreach at Christmas, which provides toys to prisoners' children. Another Prison Fellowship goal is to help local churches already involved in prison outreach to develop aftercare support programs.Mission to the Americas hopes to help develop an aftercare program for women in Illinois.

Reuniting Families

Ellen Carter will open the first Koinonia House for women in July 2000 in the Fox River Valley. Carter, husband Al, and grandson Delon will offer job support, discipleship, food, shelter, and a sense of family to six women at a time."Our ultimate aim is to reunite families," Carter says, "but you can't take a woman straight out of prison, throw her back into the same environment that put her there, and expect her to care for herself and her children."Carter says the Koinonia House will accept women who realize they need to rebuild their lives before they reunite with their children. "We are a place for people who are willing to work hard to get their lives on track so that they can give their kids what they deserve: a loving, responsible parent."While prison-ministry veterans see the trend toward aftercare as hope for breaking cycles of recidivism and restoring families, they also agree it is not enough."It is wrong that we are not dealing with the causal factors that these women face," says Bundy of the Institute for Prison Ministry. "For the most part they are not violent offenders. They are addicts. They have not graduated from high school, and they have been oppressed in abusive relationships."Bundy believes Christian community outreach should have a better balance in meeting both the spiritual and physical needs of women. "Because of the gospel, there is a lot of love and hope in the church. The church has a lot to offer to poor, desperate people whose lives are so dark they try to escape with drugs."Carter believes that her Koinonia House is just the next step in prison ministry today. "I hope to teach and disciple these women that a part of knowing Christ is passing along the knowledge of that blessing to others. The women whose lives we change should go out and help others change, too."

Discipling Women

When Carter works inside a prison, she is unyielding in her attempts to get women inmates to rethink their own lives.During a recent Bible study at the Cook County Jail, she had the full attention of nearly 100 inmates. "I came today to ask you," Carter intones, "How clean is your garden? After Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit, God cleaned out his garden. Some of you are messing around with homosexuality, with drugs, with prostitution and vileness. Some of you are sleeping with men who are not your husbands." Carter smooths her vest, which has bunched from the vigorous, sweeping motions of her silk-shirted arms, and leans forward to her audience of yearning faces. "How clean is your garden?"Women shift uncomfortably in the pews, scuffing their feet. As their only outward sign of individuality, women prisoners sport everything from pink cloth slippers and brand-name running shoes to stylish sandals. Carter pauses to let the question sink in.Then in the front row, inmate Gayle Brown bursts into tears. Gayle Brown's circumstances and sorrows are not very different from those of other incarcerated women in the U.S.Brown, a 38-year-old mother of three, does not want to live another day separated from her family, but she is afraid that even after her release her newfound faith will not be enough to patch up the pieces of their tattered lives.A 1998 study by the U.S. Department of Justice found that women offenders have different needs than men because women are more frequently victims of sexual or physical abuse and more women carry responsibility for children. "They also are more likely to be addicted to drugs and to have mental illnesses," the report says.Brown does not often talk about her failed marriage or the affair she had, which contributed to a spiral into drug abuse and ultimately a prison sentence.She has been arrested three times before, but this fourth time is especially painful because, she says, "I had lived straight for five years. I never planned on seeing this place again."Brown became involved with a man who gave her drugs when she started caring for his sickly mother, a kind neighbor of many years. All she says about the other men in her life is cutting: "I didn't have a daddy, and besides my husband, I never had a man to take care of me. Men are users through and through."More than 70 percent of all female inmates in California were victims of ongoing physical abuse before age 18. At least 40 percent of those were sexually abused or assaulted before 18, according to the recent report "Profiling the Needs of California's Female Prisons."Psychologists say that when an abused woman is in prison, she is less likely to report any kind of mistreatment by prison officials. In addition, she is more likely to experience terror at the loss of control associated with strip searches, group showers, public toilets, and overcrowded prison cells.Like the majority of women in prison, Brown worries constantly about her children. According to a 1996 study by Amnesty International, 80 percent of incarcerated women are mothers and 75 percent are single parents. Brown's sons, ages 19 and 16, and her daughter, 13, are always on her mind."I worry most for my little girl, because I don't think she's going to be able to forgive me," Brown says. "My husband left after I committed adultery and now I am not even around myself."

Meeting Individual Needs

Only 20 percent of incarcerated women's children live with a father if their mother is jailed. About 60 percent of dependent children are raised by their grandmothers, 15 percent go to foster homes, and 5 percent are cared for by other relatives. Brown's children are no exception. "They would have no place to go if my mama hadn't stepped in."Eventually, many of the children who are separated from their mothers during a prison sentence end up following their moms to jail. U.S. News & World Report polled juvenile-justice agencies in 21 states in 1999 and found in each state that between 40 and 60 percent of female juvenile offenders said their mothers were or had been incarcerated.Removing children from their only parental influence is so detrimental that in 1993 Congress authorized the National Institute of Corrections to allocate $8 million for a facility geared for women prisoners and their young children. But in the ensuing six years the NIC has failed to spend any money toward such a facility.Although saying her recent arrest for illegal drug possession was not legitimate, Brown admits that her three previous arrests were drug-related as well. More than 70 percent of women in state prisons in 1986 abused drugs before admission. In 1991 the U.S. Department of Justice found that a third of all female inmates reported committing their offense while on drugs. One in four female inmates committed crimes to get money for illicit drugs.Women are also three times more likely than men to enter prison addicted to cocaine. Often, like Brown, offenders will do anything to deny they have an addiction for fear of extra years getting tacked on to their sentence, or in hopes of obtaining drugs surreptitiously within the prison system."If you aren't on drugs when you come into a place like this one," Brown says, motioning to the drab walls and dim corridors, "all this will make you want to start on them."Brown also admits depression is a common problem for inmates. A study by Northwestern University between 1991 and 1993 found "substantial psychiatric morbidity" among female detainees at the Cook County Jail. Researchers found that many women inmates suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.The rate of recidivism for women who do not receive any type of counseling while imprisoned is significantly higher than the 20 to 30 percent rate for the women who do receive some form of support.Abuse, motherhood, drug addiction, and health factors combine to favor ministry tailored to individual needs. When Brown breaks down in the middle of Carter's chapel sermon, a prison chaplain's wife embraces her and prays with her."It will take something as big and powerful as Jesus to change my life," Brown says. "You feel like that is possible when someone prays with you and talks about the Bible. I just pray that I get the chance to go home and see my kids again."

Cultivating New Hope

The idea of passing on what God teaches is at the heart of Carter's ministry. Carter believes in discipleship because that is what changed her life.Carter was raised by her grandparents in a strict, old-fashioned church in a poor neighborhood in Maryland. "I knew all the stories about Jesus, but I had no idea that I needed to know him personally," she recalls.After struggling to complete high school, she was studying nursing when she got pregnant at 18. A series of failed relationships and jobs led her to conclude that she was "wandering around with an empty heart." Riding home one day, she spotted clusters of smiling people pouring out of First Baptist Church of Highland Park, and leaned over to tell her daughter that they were going to see that place close up.On Easter Sunday 1986 Carter realized that Christ had died for her and that she would have to give her life to him in response. Her second husband, Alveris Delon Carter Jr., made the same decision a year later."We were a couple of babes, and we wouldn't have known what to do, how to live, if it wasn't for Michael Durant [a member of First Baptist], who discipled my husband and then me."Carter originally served in First Baptist's prison ministry because her husband was helping men in jail. She was often fearful and hated public speaking."I almost fainted, I mean, I was on the point of tears one evening when they asked me to read the Scripture for the sermon out loud," Carter says. "But I kept getting encouraged to go disciple the women. The very first woman in prison I ever met was named Xena. I will never forget!"Carter was touched by Xena's plight: she was a single parent with four kids and no family member was willing to care for them. Carter determined to pray that Xena would be released to care for her children. She was crushed to discover after four months of prayer that Xena had been sentenced to five years in prison and transferred to another facility."I didn't go back to the prison for six months, I was so devastated," Carter sighs, "but God had other ways of working on me. My son, the apple of my eye, he was arrested and I felt like someone had stabbed me. I was like a zombie." Carter was so depressed that she would get out of bed to go to work but crawl back in as soon as she got home.After months of her husband's promptings, Carter finally agreed to meet with Deacon Carl Felton, who ran the prison ministry at First Baptist, to discuss her anger and pain. Felton took her to visit her son in prison and helped her realize that God had a plan to bring good out of her pain and sorrow."That was when God first made my dream of a Koinonia House real to me," Carter says, flashing her blinding grin. "It's all based on Jeremiah 29. God says he has plans to give us a future and a hope. That is what the women I see at the jail need to know."Carter's voice glows as she speaks of family picnics, teaching job-interview skills, and even cooking with the released prisoners she will disciple."We have plenty of women who are willing to visit the jail and help preach the gospel or pray with the inmates," Carter says."What we need is people who are willing to go beyond that. We need people who will form friendships, who will come alongside them and say, 'I will help you succeed.'"Jody Veenker is Editorial Resident forChristianity Today.

Related Elsewhere

For more on prison ministry, see Prison Fellowship Ministries, Bill Glass Ministries, International Prison Ministry,See a related article at @grassroots.org, "Prison Ministries With Women."Recent Christianity Today articles on prison ministry include:Prison Alpha Helps Women Recover Their Lost Hopes (Oct. 4, 1999)Go Directly to Jail (Sept. 6, 1999)Redeeming the Prisoners | Prison ministers embrace 'restorative justice' methods. (Mar. 1, 1999)Unique Prison Program Serves as Boot Camp for Heaven (Feb. 9, 1998)Maximum Security Unlikely Setting for Model Church (Sept. 16, 1996)for a history of Christian ministry in women's prisons, see Christian History magazine's article, "Brutality Behind Bars | Women's prisons were hellish places before Elizabeth Fry started working there."January 10, 2000 Vol. 44, No. 1, Page 52

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.