Jamaica guards its reputation as a tourist paradise—literally. Earlier this year, the government dispatched its military to make sure nothing bad happened at or near tourist destinations such as Negril and Montego Bay.

Meanwhile, throughout the spring and summer, the cities most Jamaicans live in were war zones, claiming the lives of residents, soldiers, and gang members. More than 500 people were killed between January and July on this island nation of 2.6 million. Prime Minister P. J. Patterson instituted a curfew in the capital city of Kingston and its suburbs and sent troops into the city with wide-ranging powers, saying they will be “a permanent fixture.”

Violence has flared up every few weeks in Jamaica for various reasons. In April, nine people were killed in island-wide riots after the government attempted to institute a 45-cent increase in the gas tax. In June and July, a spate of gang warfare forced hundreds of Jamaicans to flee their homes. Also in July, the unprovoked killing of a former police officer by other officers inspired riots. (Jamaican police have killed 240 civilians since January 1998.)

“These riots were really just an outgrowth of other difficulties,” says Rennard White, director of the Jamaica Association of Evangelicals. “People are demanding to be heard and will show their discontent in extreme measures.”

VISIBLE, BUT DIVIDED, CHURCH: As social problems and violence reach a boiling point in Jamaica, many have turned to the church for assistance and guidance.

“Jamaica is a very religious country in many ways,” says White. “And the church is one of its strongest voices.”

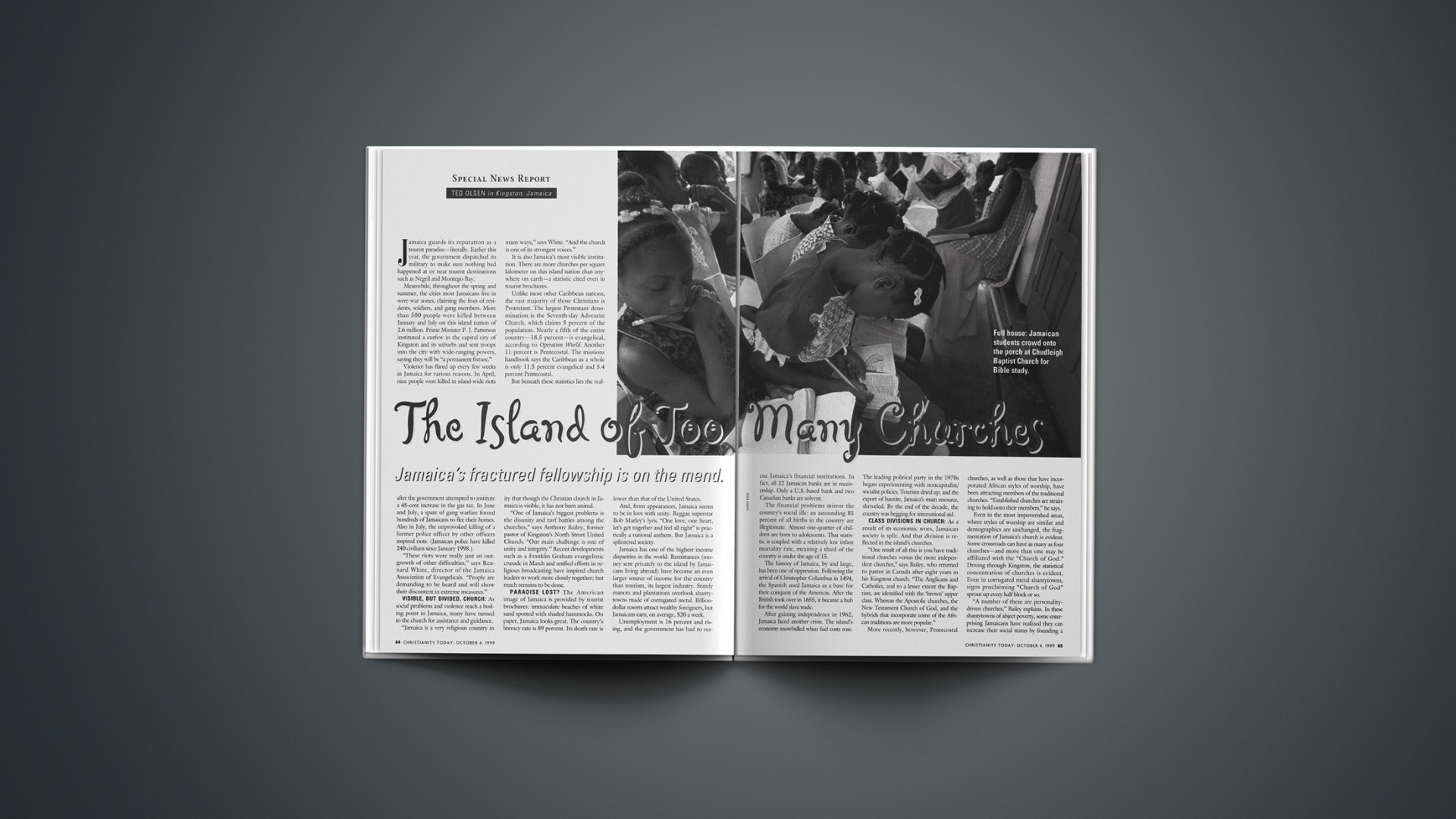

It is also Jamaica’s most visible institution. There are more churches per square kilometer on this island nation than anywhere on earth—a statistic cited even in tourist brochures.

Unlike most other Caribbean nations, the vast majority of those Christians is Protestant. The largest Protestant denomination is the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which claims 5 percent of the population. Nearly a fifth of the entire country—18.5 percent—is evangelical, according to Operation World. Another 11 percent is Pentecostal. The missions handbook says the Caribbean as a whole is only 11.5 percent evangelical and 5.4 percent Pentecostal.

But beneath these statistics lies the reality that though the Christian church in Jamaica is visible, it has not been united.

“One of Jamaica’s biggest problems is the disunity and turf battles among the churches,” says Anthony Bailey, former pastor of Kingston’s North Street United Church. “Our main challenge is one of unity and integrity.” Recent developments such as a Franklin Graham evangelistic crusade in March and unified efforts in religious broadcasting have inspired church leaders to work more closely together; but much remains to be done.

PARADISE LOST? The American image of Jamaica is provided by tourist brochures: immaculate beaches of white sand spotted with shaded hammocks. On paper, Jamaica looks great. The country’s literacy rate is 89 percent. Its death rate is lower than that of the United States.

And, from appearances, Jamaica seems to be in love with unity. Reggae superstar Bob Marley’s lyric “One love, one heart, let’s get together and feel all right” is practically a national anthem. But Jamaica is a splintered society.

Jamaica has one of the highest income disparities in the world. Remittances (money sent privately to the island by Jamaicans living abroad) have become an even larger source of income for the country than tourism, its largest industry. Stately manors and plantations overlook shantytowns made of corrugated metal. Billion-dollar resorts attract wealthy foreigners, but Jamaicans earn, on average, $20 a week.

Unemployment is 16 percent and rising, and the government has had to rescue Jamaica’s financial institutions. In fact, all 22 Jamaican banks are in re ceiv er ship. Only a U.S.-based bank and two Canadian banks are solvent.

The financial problems mirror the country’s social ills: an astounding 85 percent of all births in the country are illegitimate. Almost one-quarter of children are born to adolescents. That statistic is coupled with a relatively low infant mortality rate, meaning a third of the country is under the age of 15.

The history of Jamaica, by and large, has been one of oppression. Following the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1494, the Spanish used Jamaica as a base for their conquest of the Americas. After the British took over in 1655, it became a hub for the world slave trade.

After gaining independence in 1962, Jamaica faced another crisis. The island’s economy snowballed when fuel costs rose. The leading political party in the 1970s began experimenting with noncapitalist/socialist policies. Tourism dried up, and the export of bauxite, Jamaica’s main re source, shriveled. By the end of the decade, the country was begging for international aid.

CLASS DIVISIONS IN CHURCH: As a result of its economic woes, Jamaican society is split. And that division is reflected in the island’s churches.

“One result of all this is you have traditional churches versus the more independent churches,” says Bailey, who returned to pastor in Canada after eight years in his Kingston church. “The Anglicans and Catholics, and to a lesser extent the Baptists, are identified with the ‘brown’ upper class. Whereas the Apostolic churches, the New Testament Church of God, and the hybrids that incorporate some of the African traditions are more popular.”

More recently, however, Pentecostal churches, as well as those that have incorporated African styles of worship, have been attracting members of the traditional churches. “Established churches are straining to hold onto their members,” he says.

Even in the most impoverished areas, where styles of worship are similar and demographics are unchanged, the fragmentation of Jamaica’s church is evident. Some crossroads can have as many as four churches—and more than one may be affiliated with the “Church of God.” Driving through Kingston, the statistical concentration of churches is evident. Even in corrugated metal shantytowns, signs proclaiming “Church of God” sprout up every half block or so.

“A number of these are personality- driven churches,” Bailey explains. In these shantytowns of abject poverty, some enterprising Jamaicans have realized they can increase their social status by founding a church and declaring themselves pastor.

Jamaican pastors’ biggest concern about having so many churches in so little space is the competition and sheep stealing inherent in such a situation.

“A lot of switching goes on naturally,” Bailey says, “but some churches make a point of it.” He is most concerned about Jamaica’s Seventh-day Adventists, who have nearly 500 congregations on the island.

“It’s big and it’s growing,” he says. Bailey contends that Adventists’ evangelistic campaigns are geared to “scaring people into the church” by preaching “they’re going to hell” if they do not join the denomination.

Adventists disagree with the complaint.

“There are different philosophies in evangelism,” says Noel Fraser, Kingston-based secretary of the West Indies Union Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. “That’s always been the sore point among Protestants everywhere. No pastor wants to see people leaving their church for another. But if they agree with freedom of religion, they have to be big enough to accept it when people leave.”

But Fraser readily concedes that competition among churches is the biggest issue facing Jamaica’s Christians. “In tolerance has always been a defect among us, even though there’s a greater spirit of tolerance today than there has been,” he says. “Every one’s work is essential.”

BLAME AMERICA FIRST? Jamaica’s current problems are its historical ones, compounded with centuries of oppression from the outside. So it goes with the disunity of Jamaica’s churches.

Gerry Seale, general director of the Evangelical Association of the Caribbean (EAC), says that, for better or worse, the missionary zeal of evangelicals in the United States is one of the largest causes of Jamaica’s proliferation of churches.

“Throughout the Caribbean we have a lot of evangelical churches because of our proximity to North America,” he says. “During the era when North America dominated the world’s missionary force, the Caribbean was easy to reach, was much less expensive than going to Africa or Asia, and produced relatively quick results.”

Though Seale bemoans the competition among Jamaica’s churches, he sees the plethora as beneficial. “The gospel is now within the reach of every Jamaican,” he says. “Every Jamaican can walk to church.”

Indeed, that has been the goal of many church plantings by North American missions groups visiting the island. But now that Jamaica is saturated with congregations, why are some groups still planting more? Some church leaders disagree with Seale’s statement that everybody can walk to church.

“There are still sections and communities not served by churches,” Fraser explains. “There are even many places in and around Kingston that are not heavily evangelized. As the population increases, we have to plant new churches.”

And leaders in many denominational churches with strong doctrinal beliefs are not concerned that Jamaica has more churches per square kilometer than anywhere else in the world. They merely see that their congregations are not as widespread as they would like. For example, the Church of Christ, which is concentrated mainly in the southern United States, is well on its way to fulfilling its goal of planting a church in every city, town, and village in Jamaica.

Historically speaking, however, when missionaries pull out, more than just new church buildings remain. Many missionaries have sowed discord. “Throughout the Caribbean there is definitely a strong competitive spirit left behind by the missionaries who taught us to distrust people outside our own denominations,” Seale says.

In light of the personality cults and fly-by-night churches, wariness was necessary.

“Ecumenism has its pluses and minuses,” says Adventist Fraser. “Churches can be corrupt.” In many cases, wariness became distrust.

COMPETITION STIFLES PROJ ECTS: North Street United Church’s Anthony Bailey also attributes much of the religious competition to political competition. “The church is seminally involved in state issues here and always has been,” he says. “At every official function, clergy are invited. There’s an unbreakable link between church and state that you don’t have in the States.”

On one hand, that has been a good deal for both church and state. The church has been able to take stands, such as coming together last spring to fight casino gambling on the island.

Because tourism is Jamaica’s biggest industry, casinos seem to be a natural moneymaker. “Politicians have had their own opinions, but they’ve listened to the churches so far,” says Fraser. “Each time the issue comes up, it looks more likely to happen, but so far they’ve listened to the church.”

But Fraser and other pastors lament that some of their colleagues have been mesmerized by their political role.

“You know the saying about power corrupting? Even the church, if it gains power, will become corrupted to some degree.”

But even if pastors steer clear of corruption, there are so many competing for leadership positions and governmental dollars that some relief projects are rendered impotent.

“Not everybody has to build a school, for example,” says Bailey. But doing so is a proven way for pastors to become more prominent in their community. “So when we tried to start one, the funding dried up because there’s so many people trying to do it.”

The EAC’s Seale agrees that the competition is stifling evangelical efforts at urban reform. While he finds hope in the sheer number of churches in Jamaica, he says he is “trying to balance that statistic with the reality of so many children born in Jamaica outside of wedlock. There remains much work to be done in discipleship to complement the work being done in evangelism.”

SUSPICIONS SUBSIDING: Though the efforts may not be as coordinated as some would like, many of Jamaica’s churches have seen themselves as essential to the country’s relief efforts. The Jamaican people have seen the churches that way, too.

“With the financial crisis and the riots, people have been coming to church as never before,” says Rhoda Williams, secretary of the Jamaican Evangelistic Association. “They’re coming seeking help—not just spiritual help, but also to help them find jobs and other assistance.”

But to be truly successful, Jamaica’s church leaders agree they need to coordinate their efforts better. And they are working together more than ever before.

“I sense an openness and a willingness to work with other groups,” says White of the Jamaica Association of Evangelicals (JAE). White says competition is still common among Jamaica’s churches, but adds, “I wouldn’t call it fierce.”

Bailey points to the JAE, a member body of the World Evangelical Fellowship, as evidence of hope for the future. He says congregational and denominational leaders have awakened to the lack of communication and trust among themselves and started crossing traditional boundaries.

“Unfortunately,” he adds, “even these umbrella organizations are fragmented.”

The JAE is only one ecumenical organization on the island. Mainline churches meet in the Jamaican Council of Churches (JCC), and Pentecostals have the Jamaica Association of Full Gospel Churches (JAFG), the Jamaican Pentecostal Union, and the Association of Gospel Assemblies. There is some crossover, but it is not widespread. The Salvation Army, for instance, belongs to both the JAE and the JCC, and some Full Gospel churches have dual membership in the JAE. The groups had not worked together on a major project until this year.

In March, the umbrella organizations joined to organize Celebrate Jesus ’99, a monthlong, islandwide evangelistic crusade of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA). Franklin Graham was the main draw, attracting 70,000 to services in Kingston. Meetings were also held in nine other cities, and the BGEA estimates that more than 250,000 people attended—about 10 percent of Jamaica’s population.

Alston Henry, pastor of Kingston’s Open Bible Church and chair of the crusade’s local executive committee, says the crusade was the most extensive in the nation’s history, and the cooperation among churches was unprecedented. It marked the first time the JAE, JCC, JAFG, and Church of God in Jamaica ever officially coordinated their efforts.

“The support came in across the church not only in terms of volunteers but also financially,” he says. “I’d be very surprised if these churches and umbrella groups didn’t work together again very soon. There is every indication that there was enough goodwill expressed here that they will.”

UNITING THEIR VOICES: Noel Fraser says the Seventh-day Adventist Church is “moving along with caution” in its process of joining the Jamaican Council of Churches. It now retains observer status and is not a full-fledged member. As the largest denomination in Jamaica—and as one accused of causing some of the rifts among churches—involvement could help the umbrella organizations have a stronger voice.

In the meantime, the umbrella groups are trying to present a united voice through the National Religious Media Commission, which runs Love FM (now Jamaica’s third-ranked radio station) and launched Love TV last summer. The commission has an even broader backing than the Franklin Graham crusade, sponsored by all seven of Jamaica’s umbrella organizations: the JAE, JCC, JAFG, the Church of God in Jamaica, the Jamaican Pentecostal Union, and the Seventh-day Adventists.

Jamaica’s churches have also come together to sponsor ecumenical prayer breakfasts and prayer vigils in the wake of the country’s recent violent outbreaks. Though some pastors have criticized the breakfasts as cozying up to the government, even these critics hope to combine forces with other denominations to re duce the nation’s crime and violence.

Copyright © 1999 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.