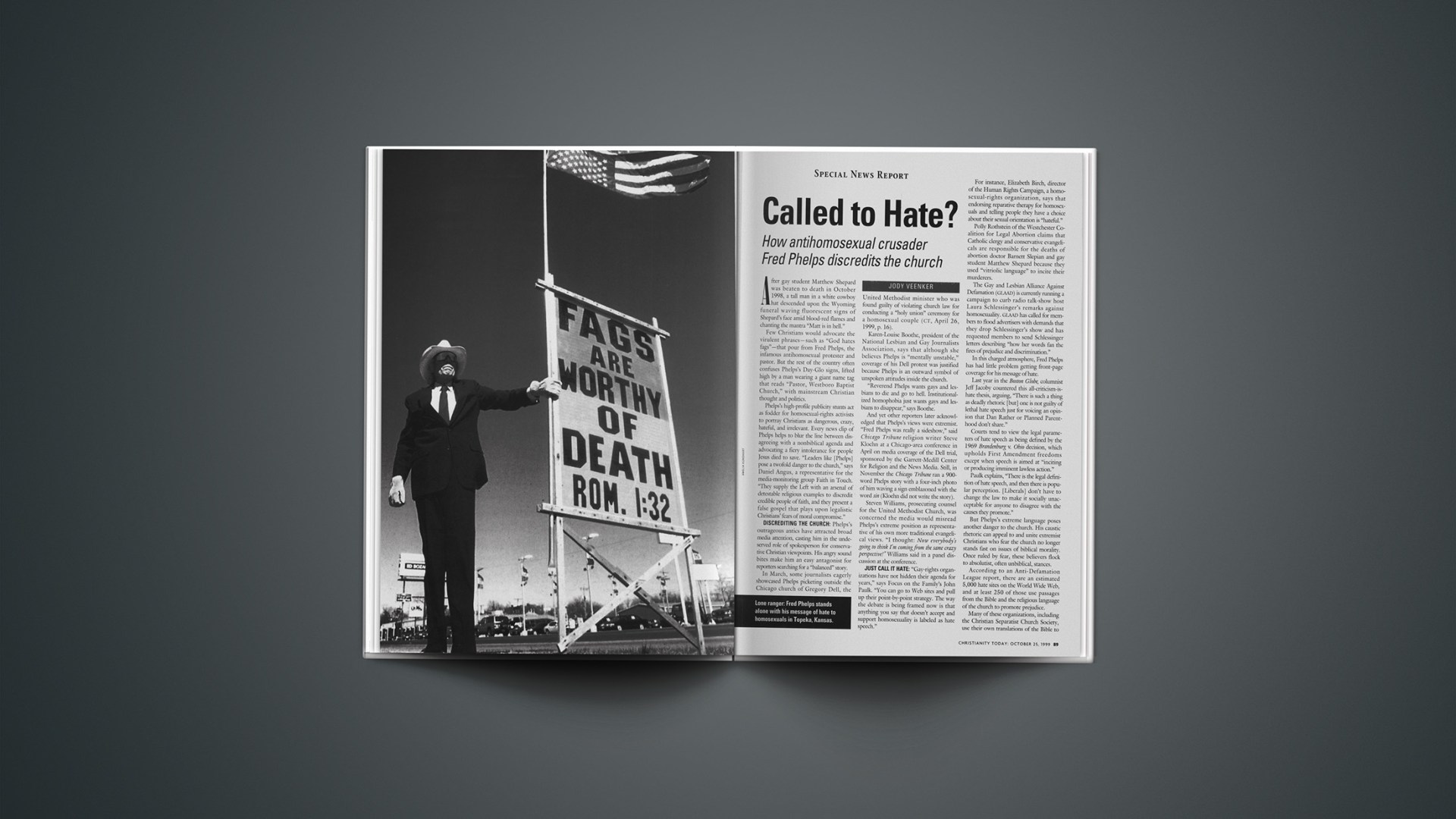

After gay student Matthew Shepard was beaten to death in October 1998, a tall man in a white cowboy hat descended up on the Wyoming funeral waving fluorescent signs of Shepard’s face amid blood-red flames and chanting the mantra “Matt is in hell.”

Few Christians would advocate the virulent phrases—such as “God hates fags”—that pour from Fred Phelps, the infamous antihomosexual protester and pastor. But the rest of the country often confuses Phelps’s Day-Glo signs, lifted high by a man wearing a giant name tag that reads “Pastor, Westboro Baptist Church,” with mainstream Christian thought and politics.

Phelps’s high-profile publicity stunts act as fodder for homosexual-rights activists to portray Christians as dangerous, crazy, hateful, and irrelevant. Every news clip of Phelps helps to blur the line between disagreeing with a nonbiblical agenda and advocating a fiery intolerance for people Jesus died to save. “Leaders like [Phelps] pose a twofold danger to the church,” says Daniel Angus, a representative for the media-monitoring group Faith in Touch. “They supply the Left with an arsenal of detestable religious examples to discredit credible people of faith, and they present a false gospel that plays upon legalistic Christians’ fears of moral compromise.”

DISCREDITING THE CHURCH: Phelps’s outrageous antics have attracted broad media attention, casting him in the undeserved role of spokesperson for conservative Christian viewpoints. His angry sound bites make him an easy antagonist for reporters searching for a “balanced” story.

In March, some journalists eagerly showcased Phelps picketing outside the Chicago church of Gregory Dell, the United Methodist minister who was found guilty of violating church law for conducting a “holy union” ceremony for a homosexual couple (CT, April 26, 1999, p. 16).

Karen-Louise Boothe, president of the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association, says that although she believes Phelps is “mentally unstable,” coverage of his Dell protest was justified because Phelps is an outward symbol of unspoken attitudes inside the church.

“Reverend Phelps wants gays and lesbians to die and go to hell. Institutionalized homophobia just wants gays and lesbians to disappear,” says Boothe.

And yet other reporters later acknowledged that Phelps’s views were extremist. “Fred Phelps was really a sideshow,” said Chicago Tribune religion writer Steve Kloehn at a Chicago-area conference in April on media coverage of the Dell trial, sponsored by the Garrett-Medill Center for Religion and the News Media. Still, in November the Chicago Tribune ran a 900-word Phelps story with a four-inch photo of him waving a sign emblazoned with the word sin (Kloehn did not write the story).

Steven Williams, prosecuting counsel for the United Methodist Church, was concerned the media would misread Phelps’s extreme position as representative of his own more traditional evangelical views. “I thought: Now everybody’s going to think I’m coming from the same crazy perspective!” Williams said in a panel discussion at the conference.

JUST CALL IT HATE: “Gay-rights organizations have not hidden their agenda for years,” says Focus on the Family’s John Paulk. “You can go to Web sites and pull up their point-by-point strategy. The way the debate is being framed now is that anything you say that doesn’t accept and support homosexuality is labeled as hate speech.”

For instance, Elizabeth Birch, director of the Human Rights Campaign, a homosexual-rights organization, says that endorsing reparative therapy for homosexuals and telling people they have a choice about their sexual orientation is “hateful.”

Polly Rothstein of the Westchester Coalition for Legal Abortion claims that Catholic clergy and conservative evangelicals are responsible for the deaths of abortion doctor Barnett Slepian and gay student Matthew Shepard because they used “vitriolic language” to incite their murderers.

The Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) is currently running a campaign to curb radio talk-show host Laura Schlessinger’s remarks against homosexuality. GLAAD has called for members to flood advertisers with demands that they drop Schlessinger’s show and has requested members to send Schlessinger letters describing “how her words fan the fires of prejudice and discrimination.”

In this charged atmosphere, Fred Phelps has had little problem getting front-page coverage for his message of hate.

Last year in the Boston Globe, columnist Jeff Jacoby countered this all-criticism-is-hate thesis, arguing, “There is such a thing as deadly rhetoric [but] one is not guilty of lethal hate speech just for voicing an opinion that Dan Rather or Planned Parent hood don’t share.”

Courts tend to view the legal parameters of hate speech as being defined by the 1969 Brandenburg v. Ohio decision, which upholds First Amendment freedoms except when speech is aimed at “inciting or producing imminent lawless action.”

Paulk explains, “There is the legal definition of hate speech, and then there is popular perception. [Liberals] don’t have to change the law to make it socially unacceptable for anyone to disagree with the causes they promote.”

But Phelps’s extreme language poses another danger to the church. His caustic rhetoric can appeal to and unite extremist Christians who fear the church no longer stands fast on issues of biblical morality. Once ruled by fear, these believers flock to absolutist, often unbiblical, stances.

According to an Anti-Defamation League report, there are an estimated 5,000 hate sites on the World Wide Web, and at least 250 of those use passages from the Bible and the religious language of the church to promote prejudice.

Many of these organizations, including the Christian Separatist Church Society, use their own translations of the Bible to justify their views. In the Separatists’ Anointed Standard translation, every reference to holiness or purity is translated as separate and unmongrelized; Scripture can thus be invoked to argue against interracial business relationships, friendships, and marriages.

The belief systems of such religious groups are often so complex that many mainstream Christians find their reasoning hard to comprehend.

PREACHING HATE: Understanding Fred Phelps means understanding the call he received to be a latter-day prophet. That call, he says, came at a sweltering tent meeting in Meridian, Mississippi, when the elders of his church gathered around him to anoint him, using the words of Isaiah 58:1: “Shout it aloud, do not hold back. Raise your voice like a trumpet. Declare to my people their rebellion and to the house of Jacob their sins” (NIV).

When Phelps takes the pulpit at Westboro Baptist Church in Topeka, Kansas, sin is usually a large part of the sermon.

It is hard to get a clear picture of who and how many Fred Phelps leads. There are about 200 irregular visitors on the Westboro Baptist Church membership roll, but most of the 70 faithful attenders belong to the extended Phelps family of 13 adult children and 48 grandchildren.

“People always say ‘you go to church with your family’ like it’s a bad thing,” says Phelps’s grandson Ben, 24, developer of www.godhatesfags.com, the church’s official Web site. “Noah and Lot only worshiped with their families. That’s biblical to me.”

Ben admires his 70-year-old grandfather as someone with great knowledge of the Bible, and he wishes that “people would understand the whole message.”

But Phelps himself seeks out opportunities to give people the screaming sound bites. He has restaged his public protests to call down the wrath of God on “wicked sodomites” countless times, shifting the setting from a Methodist church where a homosexual marriage was performed to the Canadian consulate in Chicago to Bill Clinton’s mother’s funeral (because she was connected to “the evil one who corrupts from within the White House”).

At home, Phelps spends his time writing sermons and reading out-of-print books at a local Christian college library. The librarian leaves stacks of works by John Bunyan, Richard Baxter, and Jonathan Edwards on Phelps’s reading table.

“I was born in the wrong generation,” Phelps says. “The great preacher Charles Spurgeon called himself one of the last of the Puritans, and I can relate to that.”

On the topic of homosexuality, Phelps’s words are inflexible. “God won’t allow us to have any excuses. … Some are called to preach his message of love, and I’ve been called to preach his message of hate. Where are the old-time preachers who tell people the truth? God hates evildoers and fornicators and fags.”

Phelps defends his harsh rhetoric and epithets as coming straight from the Bible. “Fag is a biblical term,” he pro tests. “It means something to stir up fire and fan flames. That’s what these sodomites do to God’s wrath—they fuel it up.”

When challenged with Scripture that portrays God’s loving pursuit of sinners, Phelps reels off a long list of verses to prove that God hates sinners, and most of all he hates those “false followers” who love sinners. “It is a modern myth that God hates sin and loves the sinner,” Phelps exclaims.

Westboro Baptist outlines other points of its theology on the Internet. The church identifies itself as an “old time” or primitive Baptist congregation, where only the King James Version of the Bible is seen as trustworthy and where women cover their heads in church. The doctrine of predestination is strongly emphasized, and Arminians are denounced as “the apostate church.”

Another unusual theological side note is the church’s dating of Sodom and Gomorrah’s destruction—an event Phelps references often—as occuring in 1898 B.C.

Outside Phelps’s church, an American flag flies upside down. Phelps says this symbol should call attention to the fact that “This country is in mortal danger—we’re in distress. Our national support of perversity is bringing God’s wrath upon us.”

The Phelps family and Westboro Baptist were first drawn to protest homosexuality in public venues in 1991 after a local park became a meeting place for homosexuals. Homosexual-rights advocates learned of the Westboro picketing and rushed to Topeka to counter Phelps’s negative tirades. Soon his family was spending its own money to stage protests against homosexuality across the nation in places sure to attract media attention.

For Phelps, it became another way to fulfill the commission of his youth. This cause follows a long line of issues Phelps has sought to publicize since those early revival days. In 1947, at the age of 18, Phelps felt God directing him to preach against the fetishes of Ute and Navajo Native Americans. In 1951, Phelps had moved on to a new cause when he captured the attention of Time magazine with his brimstone preaching against petting and lust at John Muir College in Pasadena, California.

Phelps later rallied to the call of the civil-rights movement. After founding Westboro Baptist Church with his wife, Margie, in 1955, Phelps began earning a law degree from Washburn University in 1962. He then began a “crusade for righteousness” as a civil-rights attorney determined to strike down the “Jim Crow laws of (Topeka).”

Though Phelps’s law license was revoked because of his inflamed courtroom rhetoric, his efforts did make him a few friends, including Betty Dunn, the only African-American woman on the Topeka City Council. “It’s hard to believe I used to be popular,” Phelps guffaws, and then he clears his throat. “I mean I still get a lot of attention these days. Did I tell you about the time Michael Moore came to the church to film for his movie? Did you see me in George magazine?”

Phelps’s love of controversy and need for attention are only part of the force that drives his protests. At the root of his proclamations lies a bedrock belief that he should preach hate because “the Bible preaches hate. For every one verse about God’s love, mercy, and compassion, there are two verses about his vengeance, hatred, and wrath. What you need to hear is that God hates people, and that your chances of going to heaven are nonexistent unless you repent.”

The Catch-22 is that Phelps believes God “has given homosexuals up to uncleanliness, vile affections, and a reprobate mind,” and “if he has given them up to these things, he is not simultaneously drawing them to Christ.”

AN INCOMPLETE GOSPEL: Many Christians are wary of Phelps’s focus on condemnation without salvation. Some have dedicated their lives to demonstrating God’s love to homosexuals, and they say Phelps’s angry message injures the cause of Christ.

“It is heartbreaking to think of all the people who experience Christianity only in terms of hate,” says Bob Davies, the executive director of Exodus, a ministry that helps people find freedom from homosexuality. “Every time a homosexual hears someone scream how much God and Christians hate them, our message is damaged. If you tell people the church is against them, they aren’t going to go to the church for help.”

Paulk, a former homosexual who is now married and has two children, says the graciousness of two Christians stood out to him after years of condemnation.

In his mind, their love is in complete contrast to a time when the Phelps family demonstrated within a few feet of him, chanting, “God hates fags!” as Paulk rode in a gay pride parade.

“That made me fear Christians; that made them the enemy,” says Paulk. “It wasn’t until I met a Christian couple that was willing to embrace me and love me first, that I began to listen to what they had to say about the way God loved me and the truth about homosexuality.

“It is easy to judge, but it is hard to love. Their love earned them the right to speak to my life.”

See Also:

Church Leader Worships Whites

World Church of the Creator leader Matthew Hale unites racial rhetoric and religious fervor.

Copyright © 1999 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.