In this series

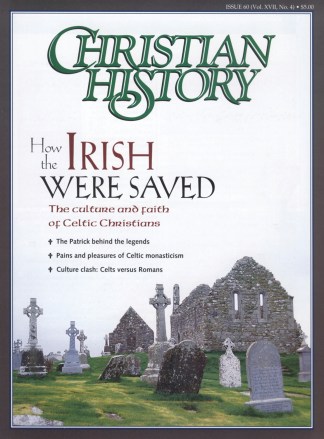

Newly emerging churches nearly always recycle old, pre-Christian ideas to serve their new faith, stitching together the pagan past and the Christian present.

In the Mediterranean world, Christian philosophers reshaped neo-Platonism. In early Christian Gaul, thousands of pagan well-spring shrines were converted into Christian sites, while Pope Gregory the Great told the English church not to destroy pagan shrines but to reuse them, “changing them from the worship of devils to the service of the true God.”

We see the same process in the early “Celtic” church—Christians who spoke the ancient Celtic languages: Gaelic, Welsh, and Pictish. These first Celtic Christians wove their new-found faith in Christ into their ancient languages and cultures. Columba, for example, reportedly blessed a Pictish well where a malign spirit lived and turned it into a Christian place of healing.

What was the nature of the Celtic Christianity that emerged from this enculturating process? Today many moderns long to find something different in Celtic Christianity—a beautiful spiritual tradition unlike the messy and compromised history of the larger Western tradition.

There is nothing distinctively Celtic about the sense of God’s presence in the natural world.

But how different was it?

Nature lovers?

“The bird which calls from the willow, / Lovely its little beak with its clear call. / Tuneful yellow bill of the firm black fellow— / A lively tune is sung, the blackbird’s voice.” So wrote one ninth-century poet in Gaelic. This kind of writing is one of the most instantly attractive aspects to modern admirers of Celtic Christianity.

Celtic Christians have left us some lovely poetry celebrating the natural world as God’s creation. But medieval Christians in England and Europe also delighted in creation. There is nothing distinctively Celtic about the sense of God’s presence in the natural world. Consider Augustine of Hippo, seeking God in and through nature’s beauties: “With a great voice they cried out, ‘He made us.’ My question was the attention I gave to them; their response was their beauty.”

Celts were also aware of the dangers of the natural world, as an eighth-century Irish prayer makes clear: “Deliver me, almighty Lord God, from all dangers of land and sea and waters, and from the phantasm of all beasts and birds and quadrupeds and serpents … from lightning, thunder, hail and snow, from rain and winds, earth’s dangers.”

Saints are often shown having dealings with animals, yes, but such stories are not illustrations of some Celtic ecological consciousness. More often they were meant to demonstrate how God’s grace and power were present in the holy man or woman.

Not just monasteries

The early Celtic church had a strongly monastic element. From the beginning, Patrick had established primitive communities of monks and nuns, just as his contemporaries had in Gaul and Italy. By the end of the seventh century, abbots controlled monasteries and “families” of monasteries whose wealth, power, and influence were enormous. In some tellings, the picture, especially of Ireland, is of a church almost entirely composed of monks (and a handful of nuns) dedicated to work and prayer.

This view is partly a result of distorted evidence. There were no cities like those in Europe, which had powerful bishops who could support libraries and scholarship on an impressive scale. In the rural Celtic world, monasteries were the only institutions with the resources to create the manuscripts we now depend on. Small rural churches serving local lay populations left no such traces.

In fact, ordinary Christians and their ministers played important parts. Laws written around A.D. 700 show that bishops had a central pastoral role. The so-called Rule of Patrick mandates “a chief bishop for every tribe, to ordain their clergy, to consecrate their churches, to be confessor to princes and chiefs, and to sanctify and bless their children after baptism.” Furthermore, the highly status-conscious laws give the bishop honor equal to that of the king.

The Rule of Patrick also describes the ordinary pastoral and sacramental roles of the clergy. They must baptize, “for there is no dwelling in heaven for the soul of someone who has not been baptized with lawful baptism.” The clergy must also say Mass and give Communion, and they must pray for and bury the dead.

Lay people and their pastors, though they have left little trace in the great monastic writings, clearly abounded in large numbers. In Ireland alone, there are more than 6,000 place-names containing the element Cill-, the old Gaelic word for church.

Praying with the Celts

Far from being culturally and religiously isolated from Europe, the Irish and Welsh prayed in Latin for most liturgical purposes, just as their Christian brothers did throughout the Western Church. We still have several Celtic manuscripts in which the prayers of the Mass, baptism, and anointing of the sick are recorded—all quite similar to those in other parts of the European church. In monasteries, the psalms formed the core of common prayer and private devotion. Psalm 118 in particular, the Beati, was greatly loved and honored: “As a man at the foot of the gallows would pour out praise and lamentation to the king, to gain his deliverance; so we pour forth lamentation to the King of Heaven in the Beati, to gain our deliverance.”

Alongside the psalms, biblical canticles (such as the Magnificat), and hymns—both Latin and vernacular—were popular.

Vernacular prayers—we have more in Gaelic than in Welsh—were less ecclesiastical in feel. They reflect a more personal or domestic use. Such prayers include praises of God, prayers to his saints, requests for protection, and blessings. Some even seem more like magical charms than prayers.

A prayer against headache runs: “Head of Christ, eye of Isaiah, forehead of Noah, lips and tongue of Solomon, throat of Timothy, mind of Benjamin, chest of Paul, joint of John, faith of Abraham: Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Hosts.”

Cult of saints

Celtic churches are also said to have had a singular devotion to their saints. But in this too they are very much like their sister churches in Europe. A vast literature focuses on the spiritual powers of these saints and of their relics and the need for devotion to them. According to one eighth-century source, a certain man died and went to heaven: he had never done any good at all, except that “on lying down and rising up he recounted the saints of the world.”

Particular saints were closely associated with particular places. Many great saints were also linked to powerful noble families, lending an aura of divine approval to whole dynasties. In fact, if a local saint was not already linked to a rising dynasty, his life story might be rewritten to give religious legitimacy to the new rulers.

Unity and difference

Far from being different, Celtic Christianity was very much like the faith of the church elsewhere. And there’s a good reason for this. A striking feature of early Celtic literature is its close connection to European writing.

The island monastery of Iona, for example, may seem exotically remote to many moderns, but it was fully immersed in the international theological culture of its age. By the early eighth century, the Iona library contained works by Basil and John Cassian, Jerome, Augustine, Philip the Presbyter, Sulpicius Severus, Athanasius, Gregory the Great, and many others.

Of course, there was also a great deal of what we might now call “folk Christianity”—the faith of a largely peasant population—as well as native poetry and lore. But monks and clergy were also great scholars in European terms and contributed greatly to international learning.

There were differences in detail between the Celtic Christians and their continental neighbors: church architecture, Easter dates, inheritance laws, and local traditions. But almost all the main features of early Celtic Christianity could be found anywhere in Catholic Europe, where every tribe and tongue and nation made the gospel their own.

The Celts found their own way of retelling the old story all the while sharing one recognizable faith.

Gilbert Márkus is a Dominican friar, Catholic chaplain at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, and an honorary research fellow in the department of Celtic of the University of Glasgow.

Copyright © 1998 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.