During the 1997-98 school year, visitors to Milwaukee’s Holy Redeemer Institutional Church of God in Christ might not have known that the students playing together actually attended two separate schools. The students wore the same uniforms, took classes in the same building, and even attended morning devotions together. Yet some of those students attended D. J. Young Academy, not Holy Redeemer. The difference? Holy Redeemer was officially a religious school, Young Academy was not.

D. J. Young Academy began in 1996 when a court injunction excluded “sectarian” schools from an expansion of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP), the nation’s first city-operated school-voucher system. The Pentecostal church decided to create a school similar to its Christian academy—then filled to capacity—but without the religious-themed textbooks. With parents’ permission, the students still received an hour of religious instruction each day, but classroom curriculum remained the same as that of Milwaukee public schools.

On June 10, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled that religious schools could participate in the program, expanding the nation’s most extensive school-choice program even further (CT, Aug. 10, 1998, p. 28). An appeal is likely.

Jerry Fair, president of both Holy Redeemer schools, says the implications for D. J. Young Academy will not be overwhelming, but the distinction between it and Holy Redeemer Christian Academy will be even more blurred.

Both schools will now use A Beka Book textbooks published by Pensacola Christian College. D. J. Young Academy will no longer need to obtain specific permission from parents for morning devotions and other religious instruction. Parents will still have the opportunity to remove their children from overtly religious activities such as morning devotions. But because every parent has chosen to enroll children in such activities, Fair does not anticipate any opting out.

Beginning with the term that starts this month, the only real difference between the two schools will be in their names.

“LANDMARK DECISION”: In recent years, voucher supporters have experienced small successes and setbacks across the nation, but the Wisconsin ruling—the first time a state’s highest court has ruled on the issue—is the most monumental victory to date for voucher proponents.

“This is a landmark decision,” says Christian Coalition executive director Randy Tate. His organization’s members have ranked the importance of school choice as second only to pro-life issues. “For years people have pointed to Milwaukee as an example of a solution that has worked, and this decision reinforces that.”

The 4-to-2 ruling draws upon federal and state court rulings dating to 1878, but relies chiefly upon the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1971 ruling in Lemon v. Kurtzman. Known as the “Lemon” test, the Court ruled that a law does not violate the Constitution’s First Amendment if it meets three requirements: it serves a secular purpose; its chief effect neither enhances nor inhibits religion; and it does not create an “excessive entanglement” between government and religion.

Wisconsin Justice Donald Steinmetz wrote for the court majority: “We hold that the amended MPCP, which provides a neutral benefit directly to the children of economically disadvantaged families on a religious-neutral basis, does not run afoul of any of the three primary criteria the Court has traditionally used to evaluate whether a state educational assistance program has the purpose or effect of advancing religion.”

About 1,500 children attended nonreligious private schools under the MPCP during the 1997-98 year. Under the court’s ruling, the program can expand tenfold. That will not happen overnight; Milwaukee’s 80 religious and 31 nonreligious private schools do not have enough seats to hold 15,000 more students. But both advocates and detractors of the program anticipate a slew of new choice schools to open in the coming years now that the go-ahead has been given.

The MPCP started as an experiment in the 1990-91 school year, with 300 students attending seven nonreligious schools. Proposed by Democratic State Rep. Annette Polly Williams and bolstered by Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson, 1 percent of Milwaukee public-school students were allowed to attend private schools at state expense. Within five years, 1,100 children had enrolled in the choice program. Academic studies on the program came out, and Thompson called the experiment a success (CT, Oct. 23, 1995, p. 76).

At the time, he argued that the trial run should be expanded into a real program, and one that included religious schools. Shortly after the governor signed the expanded program into the budget, Milwaukee teachers, the Wisconsin American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and others sued to block the program. A deadlocked Wisconsin Supreme Court returned the case to Dane County Circuit Court Judge Paul Higginbotham, who refused to lift the injunction (CT, March 3, 1997, p. 59). During the interim, a provoucher state supreme court judge replaced one who had opposed the program expansion, and he cast the deciding vote when the case, Warner Jackson v. Benson, returned.

TOMORROW, WASHINGTON? The voucher detractors who lost the suit, including the National Education Association, the ACLU, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and Americans United for the Separation of Church and State (AU), vow to appeal the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“This is as clear a set of facts as we’re going to see in a voucher case,” says AU executive director Barry Lynn. “Some of the other cases coming up are quirky and don’t have the impact that the Milwaukee case does.”

The winners are as eager to see the case go to federal court as the losers are. A positive ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court would undoubtedly encourage other states to create voucher programs. And a positive decision, voucher advocates say, is probable.

“We’re cautiously optimistic,” says the Christian Coalition’s Tate. “There’s a compelling argument to be made, particularly in regard to precedent.”

Last year, the Supreme Court ruled in Agostini v. Felton that a New York program sending state teachers into religious schools to teach remedial classes did not violate the First Amendment’s ban on establishing religion (CT, Aug. 11, 1997, p. 53). In the decision, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor noted a “significant change” in “our understanding of the criteria used to assess whether aid to religion has an impermissible effect.”

“They couldn’t have written a decision more encouraging to voucher advocates,” says Dick Komer, senior litigation attorney for the Institute for Justice, which represented the voucher advocates in the Wisconsin case. “The Supreme Court is emphasizing neutrality more. They’re saying people who’ve made religious choices can benefit as much as people who’ve made nonreligious choices.”

Though the Agostini decision makes it clear that the Supreme Court’s understanding of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause has changed, it might not have changed enough to allow vouchers for religious schools. “The Supreme Court drew a very specific line distinguishing the provision of services and the transfer of funds,” AU’s Lynn says. The Agostini ruling, Lynn says, determined that no funds would ever reach the coffers of religious schools, yet in Milwaukee, vouchers are endorsed to the school.

STATE BATTLEGROUND: Whether the Supreme Court will even accept Jackson v. Benson for review remains to be seen. “It depends on whether other voucher decisions come out at the same time,” says Komer. “That’s one reason we’re hoping the decisions come out soon.” Vouchers and school-choice issues are on the dockets of at least five state courts.

The Ohio Supreme Court has heard oral arguments in a case regarding a Cleveland voucher program that since its inception has included religious private schools (CT, Oct. 28, 1996, p. 90). The program is similar to Milwaukee’s, so the Supreme Court may wait until it can hear both cases together. In May 1997, the Ohio Court of Appeals ruled that the Cleveland program violates church and state separation, but the Ohio Supreme Court stayed the decision. About 2,000 low-income students attend both religious and nonreligious private schools in the state’s test program.

States seem to be the most promising battleground for school-choice supporters. According to Nina H. Shokraii of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C., nearly two-thirds of the states considered a school-choice program of some kind last year, and at least 45 governors expressed support for school choice or charter schools. Many of these declarations of support, however, focused on public-school choice—the ability for parents to choose any public school they wish.

NATIONAL EFFORTS STYMIED: Still, state efforts have fared better than national ones. In May, President Clinton vetoed the first congressional voucher legislation, a plan to provide vouchers for 2,000 needy students in Washington, D.C. “We must strengthen our public schools, not abandon them,” Clinton said after the veto. “This bill is fundamentally misguided and a disservice to those children.”

Vice President Al Gore had even harsher words for voucher programs, calling them “fraudulent” and “dangerous” at a July convention of the National Education Association. (As the convention began, a rabbi led a prayer asking God for protection from vouchers and tuition tax credits.)

Voucher supporters did not have enough votes in Congress to overrule presidential vetoes on the issue; so they tried another tack: educational savings tax breaks. But in July, Clinton vetoed the Education Savings Act for Public and Private Schools. It would have provided tax-free education savings accounts for educational expenses of elementary- and secondary-school children in public, private, and home schools.

Clinton is a strong supporter of public-school choice. “Every state should give parents the power to choose the right public school for their children,” he said in his 1997 State of the Union address. “Their right to choose will foster competition and innovation that can make public schools better.”

But while federal efforts at vouchers and school choice have been thwarted, the private sector has responded with its own programs to move children out of public schools and into private ones. The most notable example is the Children’s Scholarship Fund, which will provide $200 million for 50,000 public-school students to attend private schools. Financed largely by investment banker Ted Forstmann and Wal-Mart heir John Walton, it will first be open to schoolchildren in New York, Washington, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Jersey City, New Jersey. Forstmann hopes to extend it to another 40 cities. The fund, announced June 9, has earned praise from Clinton as well as voucher supporters House Speaker Newt Gingrich and Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott.

AGAINST PUBLIC SCHOOLS? Many opponents of school vouchers are worried that supporters of the movement are driven by a dislike of public schools as much as anything else. In fact, several conservatives have called for the abolition of publicly financed schools. The Fresno, California- headquartered Separation of School and State Alliance has enlisted more than 5,700 supporters, including conservatives such as R. C. Sproul, Jr., D. James Kennedy, Howard Phillips, and Marvin Olasky. Another group, the Columbia, South Carolina-based Exodus 2000, has asked Christian parents to remove their children from public schools. AU’s Lynn thinks such attitudes are more common among evangelical leaders than the community at large.

“I don’t believe most evangelicals hate public schools, especially since they see good teachers, and their kids are learning,” he says. “But many still think that teachers in public schools are too busy throwing condoms off kindergarten rooftops.”

The Christian Coalition has attempted to avoid bashing public schools. “Public education plays a role even though there’s some concern that certain values have been taken away from the public-school system,” Tate says. “But public schools will represent the values of their communities as long as parents get involved.”

Eastern College sociology professor Tony Campolo agrees. “Seventy percent of public-school teachers are regular attenders of churches and synagogues,” he says. “Public schools are ragged on all the time, and it infuriates me.”

Campolo says there is some justification for rhetoric against public schools. “They have pressure from the ACLU and other groups and have been veering away from the Christian religion,” Campolo says. “Secular humanism has become a value system in the public schools, justifiably upsetting Christian parents.” Yet Campolo says Christian parents are pulling their children out when there are signs of improvement. “Across the country, crime is down, scores are up, and schools are getting better.”

RIGHT TO CHOOSE: Campolo believes that a voucher system could lead to sectarian attitudes like those that ripped Northern Ireland apart. “They have a program basically the same as a voucher program that allows Protestant students to go to Protestant schools and Catholic students to go to Catholic schools,” he says. “It has nurtured the animosity between those groups.”

Charles Glenn, professor at Boston University’s School of Education and one of school choice’s most respected supporters, points to another country: the Netherlands. There, 70 percent of children go to nongovernment schools. It has resulted in great benefits for the children, he says, and has not damaged schools. In fact, he says, “Every other democracy but Italy enjoys educational freedom.”

Glenn, a minister in Boston’s inner city for 40 years, rejects the argument that vouchers will force public schools to better themselves to compete for students. “Thousands upon thousands leave Milwaukee public schools each year without making it better,” he says. “You can’t assume that a monopolistic organization will improve with competition.”

Market arguments are a mistake for Christians to make, Glenn says, because markets are not always positive. “If Jack in the Box closes because it can’t compete with McDonald’s, that’s one thing,” Glenn says. “But we’re talking about children here, and it strikes me that we can’t be as callous about school closings as we are about fast-food chains.”

Instead, Glenn would rather have his fellow voucher supporters argue the justice side of school choice. “School choice already exists, but not for the poorest students,” he says. “All parents should have the right to make decisions on what is best for their children.”

JUST LIKE PUBLIC SCHOOL: For now, at least, voucher programs have surpassed the experimental stage. For administrators of those schools affected by the programs, battles over whether they should be implemented have been overtaken by how they should be implemented.

In Milwaukee, storms are brewing over the more than 300 pages of state and federal rules—governing everything from admissions and teacher certification to religious activity—that private-school administrators are being told they must follow. What angers many private-school officials is that these are administrative—not legislative—restrictions created by the Department of Public Instruction.

“By making us follow each and every rule public schools have to follow, they’re trying to create two public-school systems,” says Holy Redeemer’s Fair. Milwaukee public-schools superintendent Alan Brown has warned that private schools accepting vouchers will “look just like public schools.”

For example, Milwaukee’s five single-sex private schools have already been excluded from the program because they are not allowed in the public-school system. Even more contentious, however, is the potential threat the “opt-out” clause holds for the religious character of religious schools.

“The primary purpose of most of these schools is to spread the faith,” says Lynn. “It’s one example of the state entanglements that are just going to get greater and greater. “

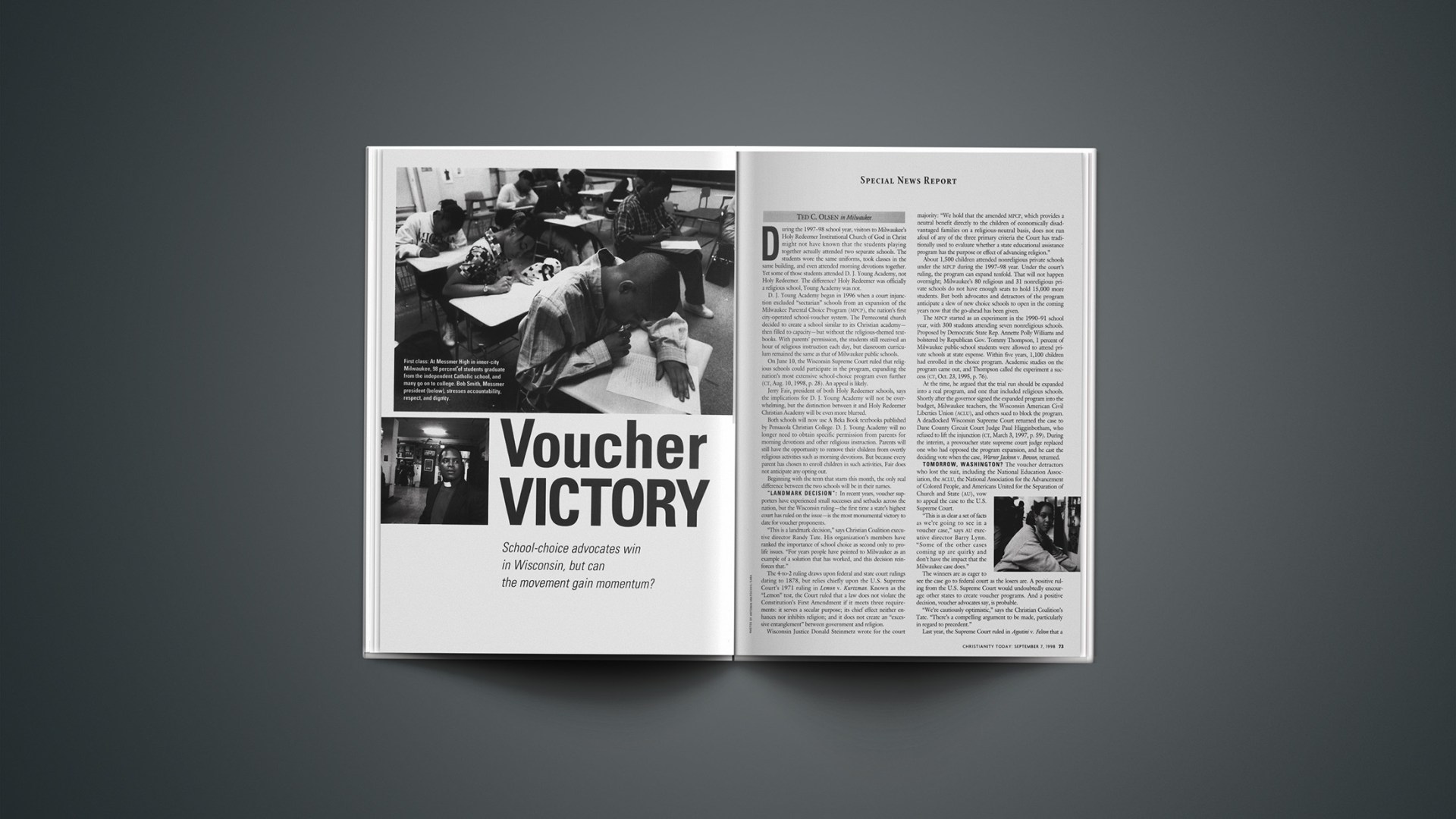

Jeff Monday, principal of Messmer High School, an independent Catholic school, says his institution interprets the “opt out” guidelines as covering only practices such as devotions, prayer, and chapel. It does not affect the use of religious texts in the classroom or the teaching of classroom subjects such as science, history, and theology.

Messmer will mandate attendance at all-school prayer services, but will allow students to sit quietly at the assemblies without praying.

While schools and administrators clash over the new regulations, observers say they do not anticipate many urban private schools opting out of the program altogether.

Though Fair is fighting the new administrative restrictions, he is no stranger to working with the system. D. J. Young Academy started when the government ruled that his school could not take voucher students. Another school at the church is a partner with the school district to educate at-risk students who were failing.

“Our priority is educating kids,” he says. “We go in the hole every year in operating costs, but you can see you’re making progress when kids’ reading scores are up one-and-a-half grades.”

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.