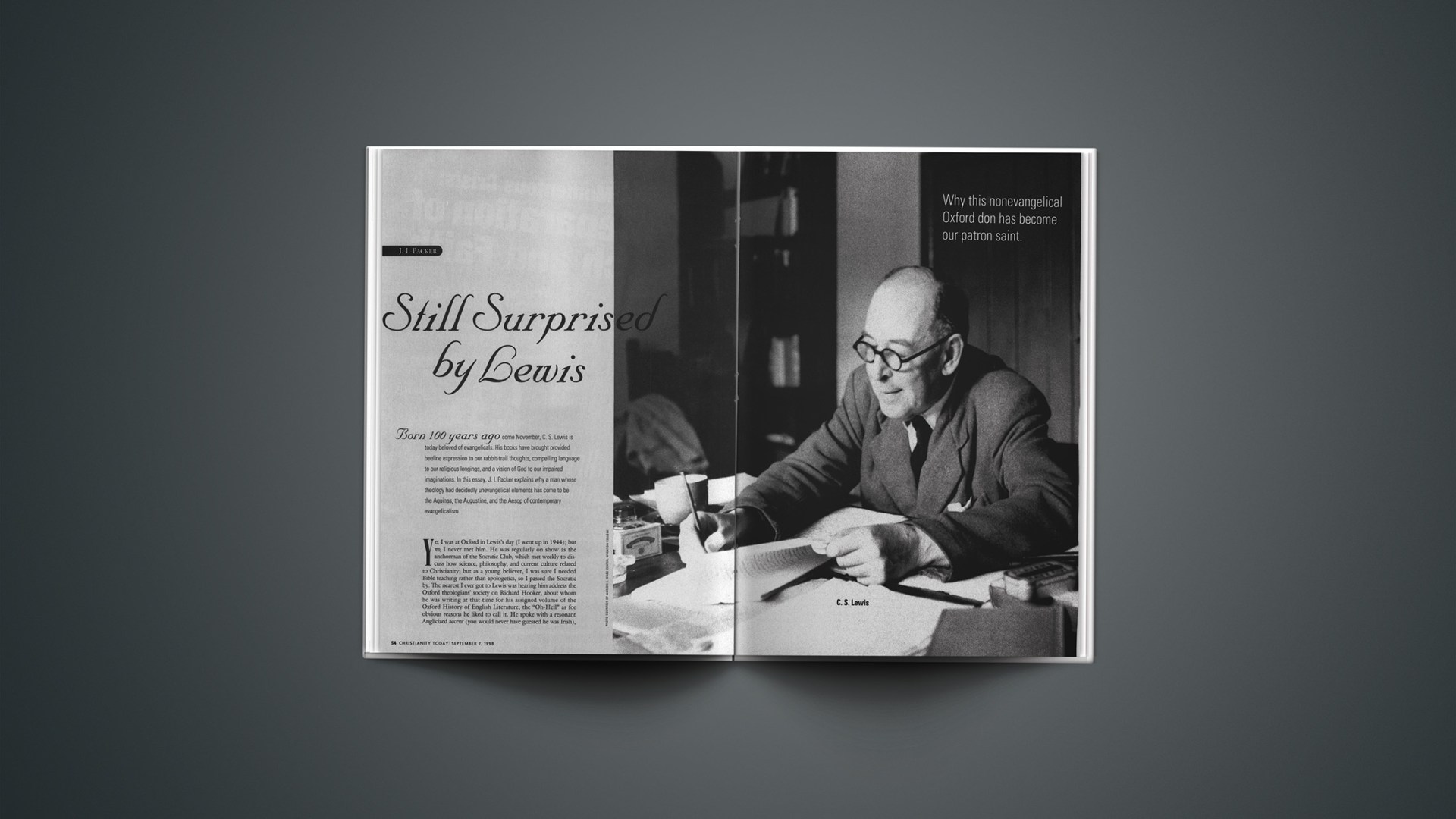

Born 100 years ago come November, C. S. Lewis is today beloved of evangelicals. His books have brought provided beeline expression to our rabbit-trail thoughts, compelling language to our religious longings, and a vision of God to our impaired imaginations. In this essay, J. I. Packer explains why a man whose theology had decidedly unevangelical elements has come to be the Aquinas, the Augustine, and the Aesop of contemporary evangelicalism.

Yes, I was at Oxford in Lewis's day (I went up in 1944); but no, I never met him. He was regularly on show as the anchorman of the Socratic Club, which met weekly to discuss how science, philosophy, and current culture related to Christianity; but as a young believer, I was sure I needed Bible teaching rather than apologetics, so I passed the Socratic by. The nearest I ever got to Lewis was hearing him address the Oxford theologians' society on Richard Hooker, about whom he was writing at that time for his assigned volume of the Oxford History of English Literature, the "Oh-Hell" as for obvious reasons he liked to call it. He spoke with a resonant Anglicized accent (you would never have guessed he was Irish), and when he said something funny, which he did quite often, he paused like a stage comedian for the laugh. They said he was the best lecturer in Oxford, and I daresay they were right. But he was not really part of my world.

Yet I owe him much, and I gratefully acknowledge my debt.

First of all, in 1942-43, when I thought I was a Christian but did not yet know what a Christian was—and had spent a year verifying the old adage that if you open your mind wide enough much rubbish will be tipped into it—The Screwtape Letters and the three small books that became Mere Christianity brought me, not indeed to faith in the full sense, but to mainstream Christian beliefs about God, man, and Jesus Christ, so that now I was halfway there.

Second, in 1945, when I was newly converted, the student who was discipling me lent me The Pilgrim's Regress. This gave me both a full-color map of the Western intellectual world as it had been in 1932 and still pretty much was 13 years later, and also a very deep delight in knowing that I knew God, beyond anything I had felt before. The vivid glow of Lewis's scenic and dramatic imagination, as deployed in the story, had started to grab me. Regress, Lewis's first literary effort as a Christian, is still for me the freshest and liveliest of all his books, and I reread it more often than any of the others.

Third, Lewis sang the praises of an author named Charles Williams, of whom I had not heard, and in consequence I picked up Many Dimensions in paperback in 1953 and had one of the most overwhelming reading experiences of my life—though that is another story.

Fourth, there are stellar passages in Lewis that for me, at least, bring the reality of heaven very close. Few Christian writers today try to write about heaven, and the theme defeats almost all who take it up. But as one who learned long ago from Richard Baxter's Saints' Everlasting Rest and Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress the need for clearly focused thought about heaven, I am grateful for the way Lewis helps me along here.

The number of Christians whom Lewis's writings have helped, one way and another, is enormous. Since his death in 1963, sales of his books have risen to 2 million a year, and a recently polled cross section of ct readers rated him the most influential writer in their lives—which is odd, for they and I identify ourselves as evangelicals, and Lewis did no such thing. He did not attend an evangelical place of worship nor fraternize with evangelical organizations. "I am a very ordinary layman of the Church of England," he wrote; "not especially 'high,' nor especially 'low,' nor especially anything else." By ordinary evangelical standards, his idea about the Atonement (archetypal penitence, rather than penal substitution), and his failure ever to mention justification by faith when speaking of the forgiveness of sins, and his apparent hospitality to baptismal regeneration, and his noninerrantist view of biblical inspiration, plus his quiet affirmation of purgatory and of the possible final salvation of some who have left this world as nonbelievers, were weaknesses; they led the late, great Martyn Lloyd-Jones, for whom evangelical orthodoxy was mandatory, to doubt whether Lewis was a Christian at all. His closest friends were Anglo-Catholics or Roman Catholics; his parish church, where he worshiped regularly, was "high"; he went to confession; he was, in fact, anchored in the (small-c) "catholic" stream of Anglican thought, which some (not all) regard as central. Yet evangelicals love his books and profit from them hugely. Why?

As one involved in this situation, I offer the following answer.

In the first place, Lewis was a lay evangelist, conservative in his beliefs and powerful in his defense of the old paths. "Ever since I became a Christian," he wrote in 1952, "I have thought that the best, perhaps the only service I could do for my unbelieving neighbors was to explain and defend the belief that has been common to nearly all Christians at all times." To make ordinary people think about historic Christianity, and to see and feel the strength and attraction of the case for it, was Lewis's goal throughout. All through his writings runs the sense that moderns have ceased to think about life and reality in a serious way and have settled instead for mindless drift with the crowd, or blind trust in technology, or the Athenian frivolity of always chasing new ideas, or the nihilism of knee-jerk negativism toward everything in the past. The Christian spokesman's first task, as Lewis saw it, is to put all this into reverse and get folk thinking again.

So his immediate goal in a sustained flow of didactic books, opinion pieces, children's stories, adult fiction and fantasy, autobiography, and poems, along with works of literary history and criticism, spread out over more than 30 years, was to stir up serious thought. About what? About the Christian values and perspectives that the people he once labeled the Clevers had left behind, and about the morasses one gets bogged down in once the Christian heritage is abandoned; and on from there. He would have agreed with the often-stated dictum of fellow evangelist Martyn Lloyd-Jones that the Christian is and must be the greatest thinker in the universe, and that God's first step in adult conversion is to make the person think.

Lewis was clear that, as he has Screwtape tell us in many different ways, thoughtlessness ruins souls; so he labored mightily by all kinds of stimulating persuasives—witty, argumentative, pictorial, fanciful, logical, prophetic, and dramatic by turns—to ensure, so far as he could, that death-dealing thoughtlessness would not flourish while he was around. His constant pummelling of his reader's mind was neither Ulster temperament nor Oxford didacticism, but the urgent compassionate expression of one who knew that the only alternative to grasping God's truth and seeing everything by its light is idiocy in one form or another.

And he believed, surely with reason, that his credibility as a Christian spokesman in an anticlerical age was enhanced by the fact that he had no professional religious identity but was just an Anglican layman earning his salt by teaching English at Oxford. As G. K. Chesterton was to himself simply a journalist with a significant Christian outlook, so Lewis was to himself simply an academic with a significant spare-time vocation of Christian utterance. Evangelicals appreciate lay evangelists of Lewis's kind.

Second, Lewis was a brilliant teacher. His strength lay not in the forming of new ideas but in the arresting simplicity, both logical and imaginative, with which he projected old ones. Not wasting words, he plunged straight into things and boiled matters down to essentials, positioning himself as a common-sense, down-to-earth, no-nonsense observer, analyst, and conversation partner. On paper he had a flair, comparable to that of the great evangelists in the pulpit (Whitefield, Spurgeon, Graham, for example), for making you feel he is in personal conversation with you, searching your heart and requiring of you total honesty in response. Never pontifical, never browbeating, and never wrapping things up, Lewis achieved an intimacy of instruction that is very unusual. Those who read today what he wrote half a century ago find him engaging and holding their attention, and when the reading is over, haunting them, in the sense that they do not forget what he said. At his best, Lewis is a teacher of great piercing power. What is his secret?

Lewis's mind was so highly developed that all of his arguments are illustrations, while all of his illustrations are arguements.

The secret lies in the blend of logic and imagination in Lewis's make-up, each power as strong as the other, and each enormously strong in its own right. In one sense, imagination took the lead. As Lewis wrote in 1954:

The imaginative man in me is older, more continuously operative, and in that sense more basic than either the religious writer or the critic. It was he who made me first attempt (with little success) to be a poet. … It was he who after my conversion led me to embody my religious belief in symbolic or mythopoeic forms, ranging from Screwtape to a kind of theologized science-fiction. And it was of course he who has brought me, in the last few years, to write the series of Narnia stories for children … because the fairy tale was the genre best fitted for what I wanted to say.

The best teachers are always those in whom imagination and logical control combine, so that you receive wisdom from their flights of fancy as well as a human heartbeat from their logical analyses and arguments. This in fact is human communication at its profoundest, for in the sending-receiving process of both lobes of the brain (left for logic, right for imagination) are fully involved, and that gives great depth and strength to what is heard. The teaching of Jesus presents itself as the supreme example here. Because Lewis's mind was so highly developed in both directions, it can truly be said of him that all of his arguments (including his literary criticism) are illustrations, in the sense that they throw light directly on realities of life and action, while all his illustrations (including the fiction and fantasies) are arguments, in the sense that they throw light directly on realities of truth and fact.

G. K. Chesterton, Charles Williams, and to some extent Dorothy L. Sayers exhibit the same sort of bipolar mental development, and what I have said of Lewis's writings can be said of theirs, too. Such minds will always command attention, and when possessed, as the minds of these four were possessed, by the values and visions of Christian faith and Christian humanism, they will always make an appeal that is hard to resist; and that appeal will not diminish as the culture changes. Visionary didacticism, as in Plato, Jesus, and Paul (to look no further) is transcultural, and unfading in its power. Bible-loving evangelicals, who build their whole faith on the logical-visionary teaching of God himself via his servants from Genesis to Revelation, naturally seek and appreciate this mode of communication in their latter-day instructors, and the consensus among them is that no twentieth-century writer has managed it so brilliantly as did C. S. Lewis.

Third, Lewis projects a vision of wholeness—sanity, maturity, present peace and joy, and finally fulfillment in heaven—that cannot but attract, willy-nilly, the adult children of our confused, disillusioned, alienated, and embittered culture: the now established culture of the West, which we shall certainly take with us (or maybe, I should say, which will certainly take us with it) into the new millennium. Both Lewis's didactic expositions (think of The Problem of Pain, The Screwtape Letters, Mere Christianity, Miracles, The Four Loves, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, and Reflections on the Psalms) and his fiction (think of the three Ransom stories, the seven Narnia tales, The Great Divorce, and Till We Have Faces) yield a vision of human life under God (or Maleldil, or Aslan, or the unnamed divinity who confronts Orual) that is redemptive, transformational, virtue-valuing, and shot through with hints and flashes of breathtaking glory and eternal delight in a world to come. To be sure, the vision is humbling, for the shattering of all egoistic pride, all Promethean heroics, and all the possessive perversions of love is part of it. In the text of all his Christian writings, and in the subtext, at least, of all his wider literary work, Lewis rings endless changes on the same story: a story of moral and intellectual corruption, embryonic or developed, being overcome in some way, whereby more or less disordered human beings, victims of bad thinking and bad influences from outside, find peace, poise, discernment, realism, fulfillment, and a meaningful future. Evangelicals love such writing: who can wonder at that?

Here we are at the deepest level of Lewis's creative identity. At bottom he was a mythmaker. As Austin Farrer, Lewis's closest clerical friend and Oxford's most brilliant theologian at that time, observed, in Lewis's apologetics "we think we are listening to an argument; in fact, we are presented with a vision; and it is the vision that carries conviction." Myth is perhaps best defined as a story that projects a vision of life of actual or potential communal significance by reason of the identity and attitudes that it invites us to adopt. Lewis had loved the pre-Christian god-stories of Norse and Greek mythology, and the thought that did most to shape his return to Christianity and his literary output thereafter was this: In the Incarnation, a myth that recurs worldwide, the myth of a dying and rising deity through whose ordeal salvation comes to others, has become a space-time fact. Both before Christ, in pagan mythology, and since Christ, in imaginative fiction from Christian and para-Christian Westerners, versions of this story in various aspects have functioned as "good dreams," preparing minds and hearts for the reality of Christ according to the gospel. With increasing clarity, Lewis saw his own fiction as adding to this stock of material.

The combination within him of insight with vitality, wisdom with wit, and imaginative power with analytical precision made Lewis a sparkling communicator of the everlating gospel.

Lewis knew that by becoming fact in Christ, the worldwide myth had not ceased to be a story that, by its appeal to our imagination, can give us "a taste for the other"—a sense of reality, that is, which takes us beyond left-brain conceptual knowledge. He found that what he now knew as the fact of Christ was generating and fertilizing within him stories of the same shape—stories, that is, that picture redemptive action in worlds other than ours, whether in the past, present, or future. In the fantasy novels (Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, That Hideous Strength, Till We Have Faces, and the seven Narnias) he became what Tolkien called a "sub-creator," producing good dreams of his own that, by reflecting Christian fact in a fantasy world, might prepare hearts to embrace the truth of Christ. The vision of wholeness that these myths project, and of the God-figures through whom that wholeness comes (think here particularly of Aslan, the Christly lion), can stir in honest hearts the wish that something of this sort might be true, and so beget, under God, readiness to accept the revelation that something of this sort is true, as a matter of fact.

Lewis once described The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe as giving an answer to the question, "What might Christ be like if there really were a world like Narnia and he chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as he actually has done in ours?" All the Narnia books elaborate that answer: Aslan's doings are a reimagining in another world of what Jesus Christ did, does, and will do in this one. George Sayer, Lewis's finest biographer, ends his chapter on Narnia by telling how "my little stepdaughter, after she had read all the Narnia stories, cried bitterly, saying, 'I don't want to go on living in this world. I want to live in Narnia with Aslan'"—and then adding the five-word paragraph: "Darling, one day you will." The power of Lewisian myth as Christian communication could not be better shown, and countless believers who have nourished their children on Narnia will resonate with Sayer here.

Nor is that all. Over and above its evangelistic, or pre-evangelistic, role, Lewisian myth has an educating and maturing purpose. Lewis's 1943 Durham University lectures, published as The Abolition of Man (whew!) with the cooler academic subtitle, "Reflections on education with special reference to the teaching of English in the upper forms of schools," is a prophetic depth charge (it has been called a harangue) embodying his acute concern about our educational and cultural future. Lewis's educational philosophy called for imaginative identification on the part of young people, with paths of truth and value foreshadowed in the Platonic tradition, focused in the biblical revelation, and modeled in such writings as Spenser's Faerie Queene and his own stories; and The Abolition of Man was the waving of a red flag at an oncoming juggernaut that would reduce education to the learning of techniques and so dehumanize and destroy it, tearing out of it that which is its true heart. (Could he inspect public education today, a half-century later, he would tell us that what he feared has happened.) His fiction, however, was meant to help in real education, moral aesthetic and spiritual—value-laden education, in other words—and it is from that standpoint that we look at it now.

A close-up on Lewis's philosophy of education is needed here. Its negative side is hostility to any reductionist subjectivizing of values, as if the words that express them signify not realities to discern and goals to pursue, but just feelings of like and dislike that come and go. As a long-term Platonist and now a Christian into the bargain, Lewis had for some time been troubled by the lurching of twentieth-century philosophy into this subjectivism, and The Abolition of Man begins as his assault on a school textbook that assumed it. Such subjectivizing, he says, produces "men without chests"; that is, adults who lack what he calls "emotions organized by trained habit into stable sentiments"—what we would call moral formation and moral character.

Positively, Lewis calls for adherence to the Tao (his term: Tao means way). The Tao is the basic moral code (beneficence, obligations and respect within the family, justice, truthfulness, mercy, magnanimity) that all significant religions and all stable cultures maintain, and that Christians recognize from the first two chapters of Romans as matters of God's general revelation to our race. Lewis sees this code as a unity, and as time-honored and experientially verified wisdom, and as the only safeguard of society in this or any age, so it is no wonder that he states its claim emphatically. Commenting on the fact that would-be leaders of thought dismiss some or all of the Tao in order to construct alternative moralities (think of Nietzsche, for instance), he declares:

This thing which I have called for convenience the Tao, and which others may call Natural Law or Traditional Morality or the First Principles of Practical Reason or the First Platitudes is not one among a series of possible systems of value. It is the sole source of all value judgments. … The effort to refute it and raise a new system of value in its place is self-contradictory. … What purport to be new systems or (as they now call them) 'ideologies', all consist of fragments from the Tao itself, arbitrarily wrenched from their context in the whole and then swollen to madness in their isolation, yet still owing to the Tao and to it alone such validity as they possess. If my duty to my parents is a superstition, then so is my duty to posterity. … If the pursuit of scientific knowledge is a real value, then so is conjugal fidelity. The rebellion of new ideologies against the Tao is a rebellion of the branches against the tree: if the rebels could succeed they would find that they had destroyed themselves.

Lewis's novel That Hideous Strength, which tells of a devilish research organization called the n.i.c.e. taking over a British university in order to take over Britain in the name of science, seems to me as to others an artistic failure, but it is a striking success in the way that it pictures this process of moral rebellion and the self-destruction to which it leads—and that, I suspect, was the only success that Lewis cared about when he wrote it.

Now, Tao-orientation is an internalized mindset that has to be learned. Lewis invokes Plato on this: "The little human animal will not at first have the right responses. It must be trained to feel pleasure, liking, disgust and hatred at those things which really are pleasant, likable, disgusting, and hateful." Yes, but how? Partly, at least, through stories that model the right responses: poems like Spenser's Faerie Queene, one of Lewis's lifelong favorites (best read, he once affirmed, between the ages of 12 and 16), novels like those of George MacDonald, and myths like the Chronicles of Narnia. Doris Myers urges that the chronicles are a more or less conscious counterpart to the Faerie Queene, modeling particular forms of virtue in a Tao frame with Christian overtones across the spectrum of a human life. Affirming that "the didacticism of the Chronicles consists in the education of moral and aesthetic feelings … to prevent children growing up without Chests," Myers reviews them to show how in each one "a particular virtue or configuration of virtues is presented, and the reader is brought to love it through participating in the artistry of the tale." The child will thus absorb the Tao by osmosis through enjoying the story.

Specifically: in the first chronicle, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Lewis works to "strengthen the Chest" by inducing an emotional affirmation of courage, honor, and limitless kindness, with an emotional rejection of cowardice and treachery. In Prince Caspian, the second, he highlights joy within responsible self-control, in courtesy, justice, appropriate obedience, and the quest for order. In the third, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the endragoning and dedragoning of Eustace, "the Boy without a Chest," is flanked by vivid images of personal nobility (Reepicheep the Mouse) and public responsibility (Caspian the captain), while a tailpiece tells us how Eustace after his dedragoning was seen to be improved—"you'd never know him for the same boy." (The image, of course, is of Christian conversion.) Numbers four and five (The Silver Chair and The Horse and His Boy) teach lessons on managing one's thoughts and feelings as one nears adulthood; number six (The Magician's Nephew) invites hatred for the life-defying development of knowledge and use of power apart from the Tao; and number seven (The Last Battle) inculcates bravery in face of loss and death.

Thus Lewis's Narnia links up with his attempt, in The Abolition of Man, to recall education to its Tao-grounded roots. The attempt was ignored, and today we reap the bitter fruits of that fact. The inner desolation and desperation that young people experience as subjectivist relativism and nihilism are wished upon them in schools and universities is a tragedy. (If you do not know what I am referring to, listen to the pop singers; they will tell you.) Yet Lewis's imaginative presentation in his tales of a life of wholeness, maturity, sanity, honesty, humility, and humaneness, fictionally envisaged in order that it might be factually realized, still has great potency for both conversion and character building, as Narnia lovers most of all will testify. And evangelical believers greatly appreciate potency of this kind.

This brings us to the fourth factor in evangelical enthusiasm for C. S. Lewis: namely, the power with which he communicates not only the goodness of godliness, but also the reality of God, and with that the reality of the heaven that exists in the fullness of God's gracious presence.

Lewis's power here stemmed from his own vivid experience. From childhood he knew stabbing moments of what he called joy, that is, intense delightful longing, Sweet Desire (his phrase), that nothing in this world satisfies, and that is in fact a God-sent summons to seek the enjoyment of God and heaven. The way he describes it is calculated (Lewis, like other writers, could calculate his effects) to focus in our minds an awareness that this experience is ours too, so that Augustine was right to say that God made us for himself and our hearts lack contentment till they find it in him, in foretaste here and in fullness hereafter. Having found Sweet Desire to be an Ariadne's thread leading him finally to Christ (the autobiographical Surprised by Joy tells us how), Lewis holds our feet to the fire to ensure, if he can, that the same will happen to us. "If we consider the unblushing promises of reward and the staggering nature of the rewards promised in the Gospels, it would seem that Our Lord finds our desires, not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us … We are far too easily pleased." Nothing must be allowed to distract us from staying the course with Sweet Desire.

Lewis's power to communicate God and heaven's reality was exerted through his marvelously vivid rhetoric. Rhetoric—that is, the art of using words persuasively—ran in the Lewis family, and C. S. Lewis himself was a prose poet whose skill with simple words, like Bunyan's, enabled him to suggest ineffable things to our imaginations with overwhelming poignancy.

Thus, in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, a momentary breeze brought the three children "a smell and a sound, a musical sound. Edmund and Eustace would never talk about it afterwards. Lucy could only say, 'It would break your heart.' 'Why,' said I, 'was it so sad?' 'Sad!! No,' said Lucy.

"No one in that boat doubted that they were seeing beyond the End of the World into Aslan's country."

And this is how The Last Battle ends:

"There was a real railway accident," said Aslan softly. "Your father and mother and all of you are—as you used to call it in the Shadowlands—dead. The term is over: the holidays have begun. The dream is ended: this is the morning."

And as He spoke He no longer looked to them like a lion; but the things that began to happen to them after that were so great and beautiful that I cannot write them … we can most truly say that they all lived happily ever after. … All their life in this world and all their adventures in Narnia had only been the cover and the title page: now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story which no one on earth has read: which goes on forever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.

The knockout quality of such writing is more than words can express.

The combination within him of insight with vitality, wisdom with wit, and imaginative power with analytical precision made Lewis a sparkling communicator of the everlasting gospel. Matching Aslan in the Narnia stories with (of course!) the living Christ of the Bible and of Lewis's instructional books, and his presentation of Christ could hardly be more forthright. "We are told that Christ was killed for us, that His death has washed out our sins, and that by dying he disabled death itself. That is the formula. That is Christianity. That is what has to be believed." Then, on the basis of this belief and the future belief that he is risen and alive and so is personally there (that is, everywhere, which means here), we must "put on," or as Lewis strikingly renders it, "dress up as" Christ—that is, give ourselves totally to Christ, so that he may be "formed in us," and we may henceforth enjoy in him the status and character of adopted children in God's family, or as again Lewis strikingly puts it, "little Christs." "God looks at you as if you were a little Christ: Christ stands beside you to turn you into one." Precisely.

Not just evangelicals, but all Christians, should celebrate Lewis, "the brilliant, quietly saintly, slightly rumpled Oxford don" as James Patrick describes him. He was a Christ-centered, great-tradition mainstream Christian whose stature a generation after his death seems greater than anyone ever thought while he was alive, and whose Christian writings are now seen as having classic status.

Long may we learn from the contents of his marvelous, indeed magical, mind! I doubt whether the full measure of him has been taken by anyone as yet.