How long have you been a Christian?” “I’m not a Christian,” the woman replied indignantly. “I’m a Messianic Jew.”

I was visiting Beth Yeshua in Philadelphia, one of the leading Messianic Jewish congregations in the United States. Though my question was poorly chosen, I was stunned by the definitive rejection of the label Christian and reminded that there may never be an easy fit between Jewish faith and 2,000 years of evolving Christian culture.

“In A.D. 150, Justin Martyr wrote to Trypho the Jew, saying, ‘You can be a Jew or a Christian, but you can’t be both.’ And that is the one thing both communities have traditionally agreed on,” says Jamie Cowen, rabbi of Tikvat Israel, a Messianic Jewish congregation based in Richmond, Virginia. “The whole thrust of Messianic Judaism is to restore the roots of the faith as a belief in Jesus as a Jewish Messiah.

“We see our mission as being two primary things—to help Jews understand Jesus as their Messiah, and to help the Christian church understand her Jewish roots.”

The rapid growth of Messianic Judaism has been remarkable. In 1967, before the Jewish people regained control of Jerusalem, there was not a single Messianic Jewish congregation in the world, and only several thousand Messianic Jews worldwide. Today, over 350 Messianic Jewish congregations—50 in Israel alone—dot the globe. There are well over one million Jews in the United States who express some sort of faith in Yeshua (the Jewish form of Jesus), according to a 1990 survey, one of the most extensive ever conducted. Sid Roth, host of the Messianic Vision radio and television show, estimates that more than 100,000 Jewish people in the former Soviet Union alone have made professions of faith.

As the numbers of Messianic Jews have increased, so has the profile of the movement grown in evangelical circles. For instance, last year’s Promise Keepers “Stand in the Gap” rally began with Messianic leaders blowing the shofar (ram’s horn) and standing with Gentile Christian leaders on the platform.

This merging of two of the three major Abrahamic religions is setting the world on edge. Many Arab observers view the phenomenon with a curious astonishment, while a number of Jews and Christians take turns attacking and defending the controversial faith of Messianic Jews.

What’s behind the numbers, the passion, and the controversy?

Strange symbols

Congregation Beth Yeshua (“House of Salvation” or “House of Jesus”) in Philadelphia is one of the leading Messianic Jewish congregations in America. It was founded by Martin Chernoff and is now led by his son, David, a messianic rabbi. It typifies the growing faith of Messianic Judaism.

You will not find a cross at Beth Yeshua. Stars of David are plentiful, but in the front of the congregation—the place where a Christian church might plant a huge wooden cross—there is an ark containing a Torah scroll (the five books of Moses).

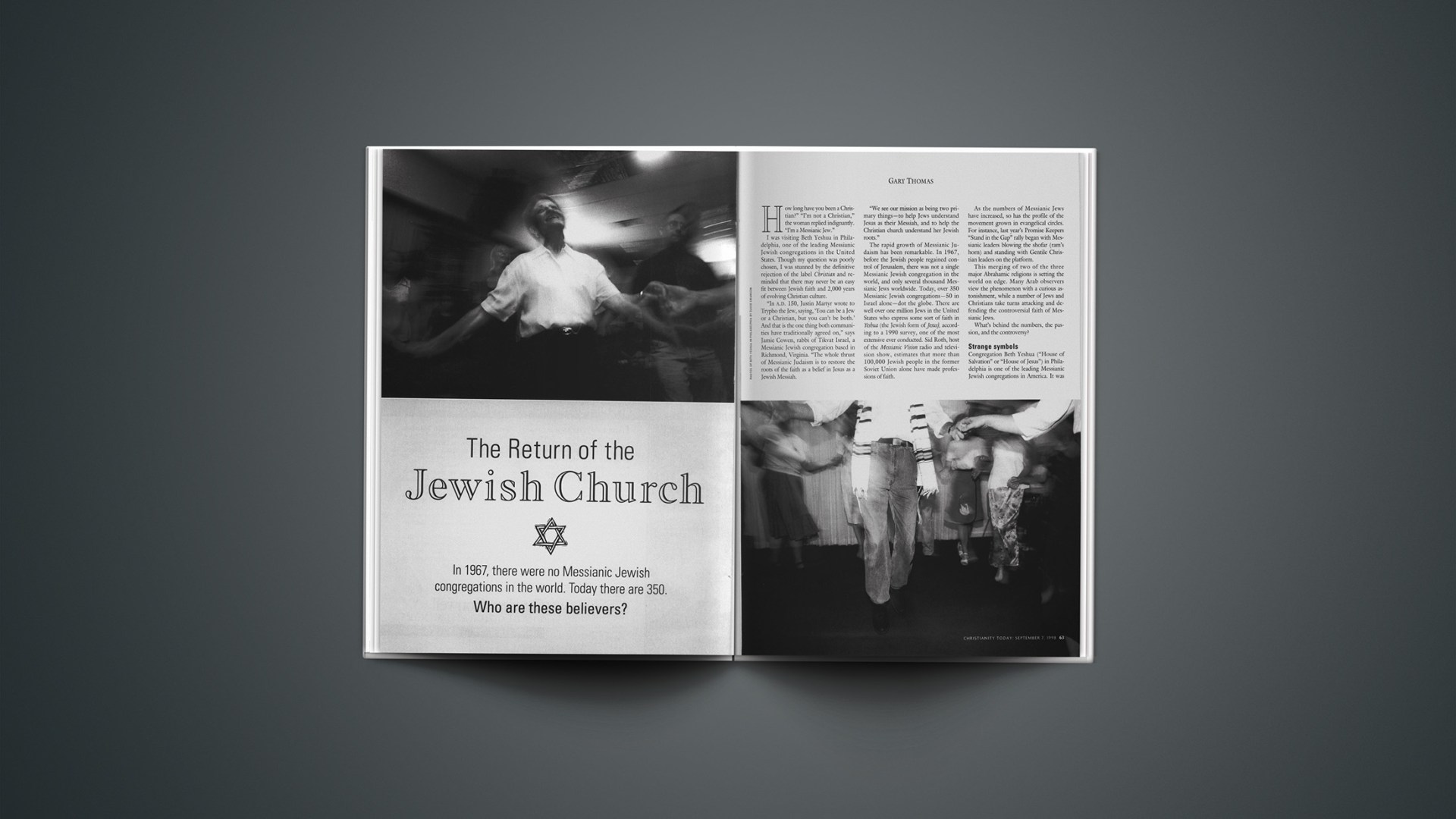

Worship services are held on Friday night and Saturday morning. Participants, including visitors, are offered a prayer shawl and a kippa (a small head covering). The service is exuberant. Chil-dren and some adults dance together in organized Jewish dances at the front of the synagogue as the worship team leads the congregation with the enthusiasm of a charismatic service.

The integration of the young and old is startling. Though children are eventually excused to go to their own classes, during the worship time the dancing and singing insure that the children are perhaps the most active participants of all. I kept thinking, “My kids would love this,” as I saw a young girl go to her seat for a quick sip from a water bottle before returning to dance some more.

The worship songs are laden with Jewish allusions and a liberal use of Hebrew. Much of the rabbi’s message sounds quite evangelical, but the frequent Hebraic references repeatedly reminded me I was not in a Gentile Christian service: instead of cross, I heard about the tree of sacrifice; and the apostle Paul is referred to as Rabbi Shaul (pronounced “Shaw-ool”).

Faith in a Jewish key

What exactly is a Messianic Jew (MJ)? The one constant is a desire to strip away centuries of Gentile accretions. “The basic point Christians must understand is that even though Jewish people may not be able to define what it means to be Jews, they feel an obligation of loyalty to their people to remain Jewish,” writes Jews for Jesus founder Moishe Rosen with his wife, Ceil, in their new book, Witnessing to Jews.

“Jewish people often have aversions to Christian symbols such as the cross, the creche and depictions of Jesus,” they write. “At the very least, those symbols puzzle Jews, who have been taught from childhood not to make images of God. At the worst, they seem to a Jewish person to verge on idolatry . …For these reasons, sometimes a messianic congregation can be very helpful in bridging the culture gap between Jewish and Gentile Christians.”

Eliezer Maass, director of training for AMF International (formerly American Messianic Fellowship), warns that “there are many different models of messianic congregations; there is a lot of diversity in this movement.”

This makes it hazardous to describe its congregations, since new expressions of worship and belief are arising all the time as the movement grows. In general, however, there are a number of cultural differences. MJs prefer “synagogue” or “congregation” to the word church, and rather than spell out God and Lord, they often use the Jewish practice of denoting respect by referring to G-d and L-rd. The Anglicized word Christ is dropped in favor of Messiah. MJs usually recognize Saturday as the Sabbath, and many still observe the rite of circumcision. Most MJs also believe that God desires the Jewish people to remain a “distinct and obedient” nation until Jesus’ second coming—hence the objection to the title Christian.

A typical Messianic Jewish synagogue will serve a variety of believers. Some are previously secular Jews who found faith in the MJ context. Others are previously evangelical Christians with Jewish blood, eager to incorporate the beloved traditions of their heritage with their belief in the Messiah. There are also Torah-observant Messianic Jews who continue to follow the strict orthodox practices of Orthodox Judaism, including kosher food preparation.

How to maintain a distinct and authentic Jewish practice has been a constant family debate throughout Messianic Judaism. Christians have not been silent as they watched from the outside. In 1975, the Fellowship of Christian Testimonies to the Jews (FCTJ) passed a resolution stating that “Christian faith is consistent with, but not a continuation of Biblical Judaism, and is distinct from rabbinical Judaism. … Bible-believing Hebrew Christians should be aligned with the local church in fellowship with Gentile believers.” The same resolution challenged the practice of wearing yarmulkes and prayer shawls, stating that “any practice of culture, Jewish or non-Jewish, must be brought into conformity with New Testament theology.”

A Messianic Jewish Alliance of America (MJAA) member responded with an article that was published in Israel My Glory Quarterly: “Why can an American remain an American and be a Christian, why can a Pole, a Russian, a Japanese, but only the Jew can no longer identify himself with his people?”

Much of this controversy between Messianic Judaism and Christianity remains today in certain circles. Many Christians have a difficult time understanding the historic persecution the Jewish people have undergone and the corresponding walls that exist between the two faiths. For centuries, Jews have seen Christians as their primary persecutors. The Inquisition, the crusades, various pogroms in Europe, and the atrocities of Nazism were waged in the name of Christianity. When you have a grandfather who was murdered in a Nazi gas chamber under a sign reading “You are being killed in the name of Jesus Christ,” it’s a bit of a stretch when an eager young evangelist tries to tell you the good news about Christianity.

Raised with such awareness, new Jewish believers often go into culture shock as they are assimilated into Gentile Christian churches. Though they are willing to believe in the Messiah who was a Jew, it is difficult to get over the atrocities that have been done in his name.

Messianic leader Stuart Dauermann explains, “Before they can seriously consider the claims of Jesus, Jewish people need a ‘cultural bed’ to rest in. The messianic congregation attempts to penetrate that cultural barrier.”

While constructing this cultural bed, many MJ leaders have removed Western elements of Christianity, including the very label Christian. That’s why many Messianic Jews will state forthrightly, “I’m not a Christian, I’m a Messianic Jew.”

“Linguistically, the terms are equivalent,” Rob Kirsch, a medical doctor and Messianic Jew, explains. “But in common thought, Christian means Gentile. Since I’m not a Gentile, I’d rather avoid a label that carries that connotation.”

‘The whole thrust of Messianic Judaism is to restore the roots of the faith as a belief in Jesus as a Jewish Messiah.’

As the only practicing Messianic mohel—a physician who performs ritual circumcision—Kirsch likes to consider himself on the “cutting edge” of Messianic Judaism. He was raised in a conservative Jewish home but met Yeshua at the age of 19 through the “slow, persistent, and dogged witness” of some college classmates.

For many years, Rob could not shake the feeling of being a “visitor” in the independent churches he regularly attended. He and his wife attempted to celebrate some of the Jewish holidays at home on their own, but they ran into many difficulties trying to assimilate their Jewish roots and their faith in Yeshua.

When Rob’s family finally came to Beth Yeshua in Philadelphia, it felt like “coming home,” he says. “I realized it was possible and appropriate to remain Jewish and be a believer, but working out how to do it was a big question for me.”

Rob was delighted to learn that the leaders of Beth Yeshua had worked out many of the issues he and his wife had confronted in trying to live the life of a Jew who believes in Yeshua.

Apart from the MJ reticence to use the label Christian, the absence of crosses is another sore point for many Western Christians who grew up singing “The Old Rugged Cross.”

“[The cross is] is synonymous with the symbol of death for all the wrong reasons,” explains Joel Chernoff, president of the International Messianic Jewish Alliance. “Due to the centuries of death and persecution of Jews by people prominently displaying that symbol, the cross has become a symbol not of the Messiah’s atonement, but of untold horror and misery.”

Joel points out that Hezekiah was willing to burn Aaron’s rod when such a dramatic symbol of Israel’s deliverance became venerated in and of itself, apart from what it represented. So, too, the Messianic Jews don’t hold symbols sacred—simply the truth behind them.

That also explains why Easter is celebrated as part of Passover. “There’s a reason the crucifixion occurred during the Passover,” Joel points out. “It loses a great deal of its power and meaning if it’s divorced from that context.”

As for Christmas, Joel notes that there is no biblical command to celebrate Christmas, so many Messianic Jews simply decide not to—though they don’t fault Gentile Christians for such celebrations.

“We have the same faith, but a different cultural practice or expression,” he points out. “In first-century Jerusalem, the early Messianic Jewish body of believers decided that the cultural worship experience of Gentile believers could be diverse, that they should hold to a few things, and then be themselves.”

The MJAA wing of Messianic Judaism is not interested in any of the cultural trappings of Gentile Christianity, unless those cultural practices reflect a specific, biblically prescribed practice.

“Christian churches are very Gentile,” admits Arthur Glasser, dean emeritus of the School of World Mission at Fuller Theological Seminary. According to Glasser, what the Messianic Jews are doing is no different from what the Chinese and German Christians are doing—working hard to contextualize a faith that supersedes all nationalistic cultures and makes sense in their own. Besides, he adds, it is the only effective way to reach a people who need the Messiah as much as anyone.

“You can’t say to the Jews, ‘You’re on the ash heap of history because you failed Jesus, and God has tossed you aside, making you of no significance. God is through with your people, but here’s the gospel through Jesus Christ.’ That’s not a very effective way to win friends and influence people,” he chuckles, adding, “You don’t have to become a Western-style Christian to worship God in a legitimate fashion.”

Some within the MJ movement are more cautious than those leading the MJAA. Maass offers the friendly, in-house critique that “sometimes the temptation is to bend over backwards and be so concerned about acculturation and being sensitive to the Jewish community to the point where Jesus becomes secondary.”

Messianic pastor Louis Lapides, a colleague of Maass’s, warns, “We risk structural damage when we hide the Messiah or drape him in so much Jewish garb that he appears to be merely a great Rabbi.”

In reality, the Gentile church doesn’t have “some kind of major say about this,” says Maas. Western Christians do not own the gospel. MJs are here to stay, regardless of how the Gentile church feels about it. In many ways, the tensions from Acts 15 and the Jerusalem council are being revisited.

Even so, Maass wants the Messianic Jewish movement to “keep those doors and channels of communication open to the Gentile church.”

The cost of belief

The personal costs that Messianic Jews pay for their faith in Yeshua are often severe, from being shunned by their families to being excluded from the local Jewish Community Center. Historically, Judaism has been a nonproselytizing faith, but now there is a full-time missionary in the United States who tries to counteract the Messianic Jewish movement. Jews for Judaism missionary Mark Powers believes that the traditional Jewish community is at one in its opposition to Messianic Judaism: “Regardless of our differences, be they political or whatever, the Jewish community is united on this issue: They [MJs] are not Jews. They are Christians. There’s nothing wrong with being Christian, but it’s just not Jewish. … It’s provable that [the messianic movement] was designed specifically as a marketing strategy to bring Jews into the church.”

Gary and Shirley Beresford, a South African Messianic Jewish couple, found out the hard way that their faith would even exclude them from being citizens of Israel. On December 25, 1989, while Christians around the world celebrated the birth of Jesus, the Israeli Supreme Court disinherited any who believed in Jesus’ name. Justice Menahem Elon wrote an opinion that stated that Messianic Jews cannot make aliyah (literally, ascent, or immigration to Israel) under the Law of Return.

“Messianic Jews attempt to reverse the wheels of history by 2,000 years,” he wrote. “But the Jewish people have decided during the 2,000 years of its history that [MJs] do not belong to the Jewish nation … and have no right to force themselves on it.”

The MJAA responded with a full-page ad in the Jerusalem Post, warning that the circle of exclusion would expand. Within seven years, that prophecy came true as the Orthodox Union of North America declared that Reform and Conservative sects are “not Judaism,” setting off a seething controversy within the Jewish community.

“It is a trifle ironic that the Reform and Conservative Jews expect Messianic Jews to abandon our Jewish identification on their demand,” observes Bruce Choen, rabbi of Congregation Beth El, a Messianic Jewish synagogue in New York City. “The issue of how exactly to define ‘Jewish’ is on the table as an ‘in-house’ issue like never before in modern Jewish history.”

Messianic Judaism is now the fastest-growing stream of faith within the Jewish community, by far, according to Joel Chernoff. The nation of Israel has not watched this explosion dispassionately. The December 1989 decision stating that Messianic Jews cannot make aliyah under the Law of Return met with little organized opposition; now the Israeli Knesset has decided to up the ante. It is currently considering a law titled “Prohibition of Inducement for Religious Conversion,” which aims to stop all proselytizing of traditional Jews. Joel Chernoff fears that the proposed law “lays the groundwork for the legalized harassment and persecution of Messianic Jews and Gentile Christians in Israel.”

The law is certainly extreme—something that you would expect to find in a Muslim nation: “Whoever possesses, contrary to law, or prints or copies or distributes or shares or imports tracts or advertises things in which there is an inducement for religious conversion is liable for one year imprisonment. Any tract or advertisement in which there is inducement to religious conversion will be confiscated.”

Although this bill is mired in committee, an even more stringent bill has been proposed (and at this writing has passed a preliminary reading in the Knesset) that calls for a three-year jail sentence and NIS 50,000 ($13,700 U.S.) fine for “anyone preaching with the intent of causing another person to change his religion.” Unlike the previous bill, this one has the support of Prime Minister Netanyahu and his cabinet.

These new rounds of legislation were proposed after American evangelist Morris Cerrullo mailed close to one million booklets to households in Israel. The booklets, written in Hebrew, made the case that Yeshua is the Messiah. As soon as the ultra-orthodox community learned of the booklets, they warned postal delivery men to cease distribution. (A few postal workers were beaten when they ignored the warnings.) All but approximately 150,000 of the booklets were delivered.

Cerullo’s organization acted independently, and there are mixed feelings within the Messianic community about what took place. While many MJs thought the booklet was well done, they recognized the potential political consequences.

Many might ask, “How could such severe legislation be seriously considered in a supposed democracy?” The answer is hinted at by Larry Derfner, a Tel Aviv journalist who wrote in a June 1997 issue of the Jerusalem Post: “Judaism may be a broad, comprehensive culture, but it has one vital organ, and that organ is religion.” In this spectrum, apparently, belief is thicker than blood.

Coalition whip Meir Sheetrit has said that this new legislation will be held down in committee, as was the case with its predecessor. Since this is the case, more important than the bills themselves may be the way the Messianic Jewish community is coming together to respond to them. “In 1989,” Joel Chernoff admits, “all we had was a loosely formed organization with several great conferences.” That has changed. There are now over 50 Messianic congregations and 30 more fellowships in Israel alone, which are being backed by the efforts of Messianic groups around the world. Together, they have formulated a strategy for political involvement to block the law’s passage.

Overture to modern Messianic Judaism

The modern manifestation of the MJ movement took almost a hundred years to develop. Its story is one of dogged determination and foresight reminiscent of Abraham himself.

The father of “Messianic Judaism” is Joseph Rabinowitz, a Russian Jew who lived from 1837 to 1899. Rabinowitz became a believer in Yeshua as he sat upon the Mount of Olives, pondering the suffering of the Jewish people. In the waning years of the nineteenth century, Rabinowitz established a Jewish Christian synagogue in Kishineff, Russia.

Just a few years after Rabinowitz’s death, Mark Levy, an English Jew, got hold of the same vision and worked to establish a similar movement in the United States. These initial efforts soon waned, but they were revived at a New York City conference in April 1915 in which the Hebrew Christian Alliance (HCA) was officially formed. An early resolution explains that the HCA sought to unite and encourage Jewish believers to come out “openly and boldly” in their confession of the Messiah. In 1925, a worldwide group, the International Hebrew Christian Alliance (IHCA), came into existence.

Though Levy was largely responsible for getting the movement started in the United States, his views regarding indigenous Jewish worship and practice were not popular until much later in this century. The immediate controversy arose over Levy’s insistence that Jewish believers be allowed (and even encouraged) to maintain practices of the Jewish faith. His argument would be forwarded two decades later by Sir Leon Levison, president of the IHCA in the thirties, who said that “Paul stood out against Judaising the Gentiles; and now [we] must plead against Gentilising the Jews.”

As anti-Semitism spread in the 1930s, particularly in European countries, the IHCA encouraged the formation of specific congregations, especially in communities where Jewish believers were not welcome in Christian churches. The Holocaust naturally impeded many evangelistic efforts well into the forties. Many Jewish believers were understandably hurt by the tepid response of Christians to the reports of wholesale Jewish slaughter. Correspondingly, they felt little or no loyalty toward the Gentile churches who turned their backs on such suffering. On an international scale, at least, the once unquestioned practice of assimilation into Gentile Christian churches began to be challenged by necessity as much as anything else.

There was a temporary revitalization of organizational efforts in 1955 when the IHCA held the World Congress of Hebrew Christians in Chicago, but interest cooled off once again, and the early sixties presaged a relatively silent decade.

That changed suddenly in 1967 when, during the Six Day War, Jerusalem was returned to Jewish control. Glasser explains that “with the establishment of the State of Israel, a new wave of Jewish concern came through a lot of American Jewish hearts.” Earlier, Glasser points out, assimilation was the “natural” route to take. But after the Holocaust and then the emergence of the State of Israel, “there was something among the Jewish people which made them feel that Israel had a future and that they should be identified with Israel in a different way.”

There is no biblical command to celebrate Christmas, so many Messianic Jews simply do not.

Paul and Bertha Swarr experienced this wave firsthand while living in Israel as Christian workers with the Mennonite Board of Missions and serving in an interdenominational church in Jaffa. The Swarrs had moved to Israel in 1957 as Protestant missionaries with little idea of Messianic Judaism, as Paul explains, but with the directive to “represent Yeshua in whatever way we could.” By the early seventies, one of the Anglican congregations was pastored by a Messianic Jew, who decided to use fewer Gentile trappings and create a more Hebraic worship context at the Beit Immanuel Messianic Congregation.

“At that stage, we made a choice to link up with what was happening at Beit Immanuel,” Paul says. By 1977, the Swarrs were pastoring Beit Immanuel, a position they continued in for ten years before returning to develop the School of Jewish Studies at the University of the Nations in Richmond, Virginia.

“In our early years there, if we saw one baptism a year, we saw it as a victory,” Paul recounts. “In our last ten years there, the growth came from the university group. When the [university group] made the discovery that Yeshua was a Jew—that they were not leaving their heritage, but discovering their heritage—they ‘owned’ what was happening. The young Israelis are wide open, and it’s now a much more demonstrative witness there.”

“Political Zionism has not met the need of their spirits,” Bertha adds. “But the young Israeli believers see themselves as a sign of hope in the Middle East.”

This explosion of interest erupted among Jewish youth in North America, too, resulting in more aggressive evangelism and more emphasis on indigenous Jewish practice. Joel Chernoff, son of the prominent Hebrew Christian leader Martin Chernoff, joined another believer, Rick Coghill, to form the highly successful recording group Lamb, and soon began pioneering a new, distinctive sound that combined Eastern European and ancient Jewish music with the pop sound of the seventies. Organizations and conferences geared toward the youth were developed to foster the burgeoning interest, and once the youth were included, Messianic Judaism would never be the same.

During this same time, the well-known Jews for Jesus (JFJ) missions organization was founded by Moishe Rosen, raising Jewish evangelism to a new pitch. Some of the Jews who became believers in Jesus were assimilated into Gentile churches. Others began joining Messianic congregations that started to form throughout the United States.

In 1975, the alliance voted to change its name from the Hebrew Christian Alliance of America to the Messianic Jewish Alliance of America (MJAA). Soon after, in 1980, the alliance headquarters moved from Chicago to Philadelphia (where it remains today), the first denominational-type organization. David Chernoff (brother of Joel) was appointed the first chairman of the steering committee, which formed the International Alliance of Messianic Congregations and Synagogues (IAMCS) in 1986. The IAMCS has since developed a program for ordination and the Institute for Messianic Rabbinic Training. In June of 1997, Joel Chernoff was elected president of the International Messianic Jewish Alliance, which represents groups in 15 nations, including Israel.

Toward Jerusalem Council II

The rise of Messianic Judaism is not only stirring religious authorities in Israel; it is also generating interest among Gentile churches. It may even lead to a significant meeting called “Toward Jerusalem Council II,” tentatively scheduled during Shavuot (Pentecost), 1999. A number of denominational leaders are coming together in an effort to “repair and heal the breach between Jewish and Gentile believers in Yeshua … primarily through humility, prayer and repentance.” The vision is for a gathering of cross-denominational representatives (Gentile and Jew) to gather in Jerusalem and produce a historic document.

Early goals include recognizing the schism between Jewish and Gentile believers, which culminated in the decrees of the Nicene Council II (A.D. 787). This would involve denouncing that council’s decree declaring Messianic Jewish communities had no right to exist.

Toward Jerusalem Council II will also seek to understand and affirm the Jewish roots of Christianity (and the validity of the Messianic Jewish community), while recognizing the “sacrificial, loving effort of true believers from among the Gentiles to share the Good News of the Messiah with the Jewish people.”

“The Church is cursed with division, because its rejection of the Messianic Jewish community [in the second century] was the first church split, which led to other church splits,” says Daniel Juster, messianic rabbi and leader of Tikkun Ministries. “The resolution of later church splits requires repentance and returning to a first-century understanding of the Bible in its original Jewish context.” Of course, some evangelicals might counter that, though the New Testament was written by Jewish writers, it was produced in a Hellenistic Graeco-Roman cultural context, not a Jewish one.

‘Despite the evils Jews have experienced at the hands of Gentiles, Jews are more responsive to the gospel today than they have been for a long time.’

At Toward Jerusalem Council II, Messianic Jews will be called on to repent of pride. Gentiles will be called to “recognize and to grieve” over the Christian church’s sins against Jewish believers in Jesus, including “all forms of ‘replacement’ teaching” (which treats the first covenant as obsolete and discarded, with the Gentile Christian church inheriting Israel’s promises). Finally, the council would call upon the church to affirm a declaration similar to that of Acts 15, affirming Jews who follow Jesus and who want to continue in their Jewish life and calling (within the context of scriptural norms).

The absolute rejection of all forms of replacement teaching will no doubt cause considerable controversy among evangelical churches. While some forms of this teaching have anti-Semitic roots, other forms can be deduced quite easily from the writings of the apostle Paul, not to mention the anonymous author of Hebrews.

A revival from within

The future of the movement is a paramount concern to many MJ leaders. “The key is the next generation—if [Messianic Judaism] survives, it will remain until the Lord returns,” says Tikvat Israel’s Cowen.

Gentiles also seem mesmerized by future implications. “Jewish people are becoming reminded of Jesus Christ in a way that they haven’t been for centuries,” Glass-er notes. “Despite the Holocaust, despite the evils Jews have experienced at the hands of Gentiles, including some Christians, Jews are more responsive to the gospel today than they have been for a long time.

“We have to ask ourselves, what is the significance of this? Is the stage being set for the return of Christ, according to Matthew 24:14? Are we living in apocalyptic times? I’m no prophet, but it seems to me that the church in our day is not paying enough attention to the truths of the coming of Jesus Christ and what that will mean to the nations and to the Jewish people.”

Outside of the Book of Romans, perhaps one of the most insightful comments regarding the turning of Jewish people toward faith in the Messiah was uttered over 75 years ago by John Zacker during a 1921 “Hebrew Christian” conference in Buffalo:

“The Jew has dwelt in every degree of latitude and longitude. His history cannot be explained by geography, climate, genius, or politics. He was scorched and chilled by the suns of Africa and the snows of Lapland. He has tasted of the Tiber, Thames, Jordan, and Mississippi. These experiences are but characteristic of the wandering Jew. He is a riddle to himself and a by-word to others. He is the paradox of history. He is proud of being a Jew and yet wishes assimilation. He boasts of religion and is an infidel. He cries for Palestine and remains in America. He is the greatest cosmopolitan and the most extreme racialist. With unsurpassing ferocity he has been smitted [sic] by papal superstition and Moslem barbarism. … Why this miraculous preservation? Because their present experiences and persecutions are but a training and preparation for ultimate conversion and through them the conversion of the human family. … But how shall the veil be torn from the faces of this indestructible people? The spiritual revival must come from within.”

What Zacker could only hope for—a spiritual revival from within—is now being witnessed by Jews such as Chernoff and Maass, and Gentiles such as Glasser and the Promise Keepers. This is no homogenous movement (see “Mapping the Messianic Jewish World,” p. 66), nor has it been without its own fights and theological squabbles.

But two things are certain. One, more Jewish people than ever before are coming to believe that the Messiah did indeed appear 2,000 years ago in the Incarnation as a Jewish carpenter. And two, Gentile Christians may find that they no longer “own” the gospel in the way they have since the mid-second century. Jesus the Messiah is for all nations, and now he is reaching back to reclaim the first of the three major Abrahamic faiths. While no one is certain how all this will turn out, it is clear that faith in Yeshua, or Jesus, is breaking new ground.

Gary Thomas is author of The Glorious Pursuit: Embracing the Virtues of Christ, to be released by NavPress this September. This article included reporting by Carolyn McCulley.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.