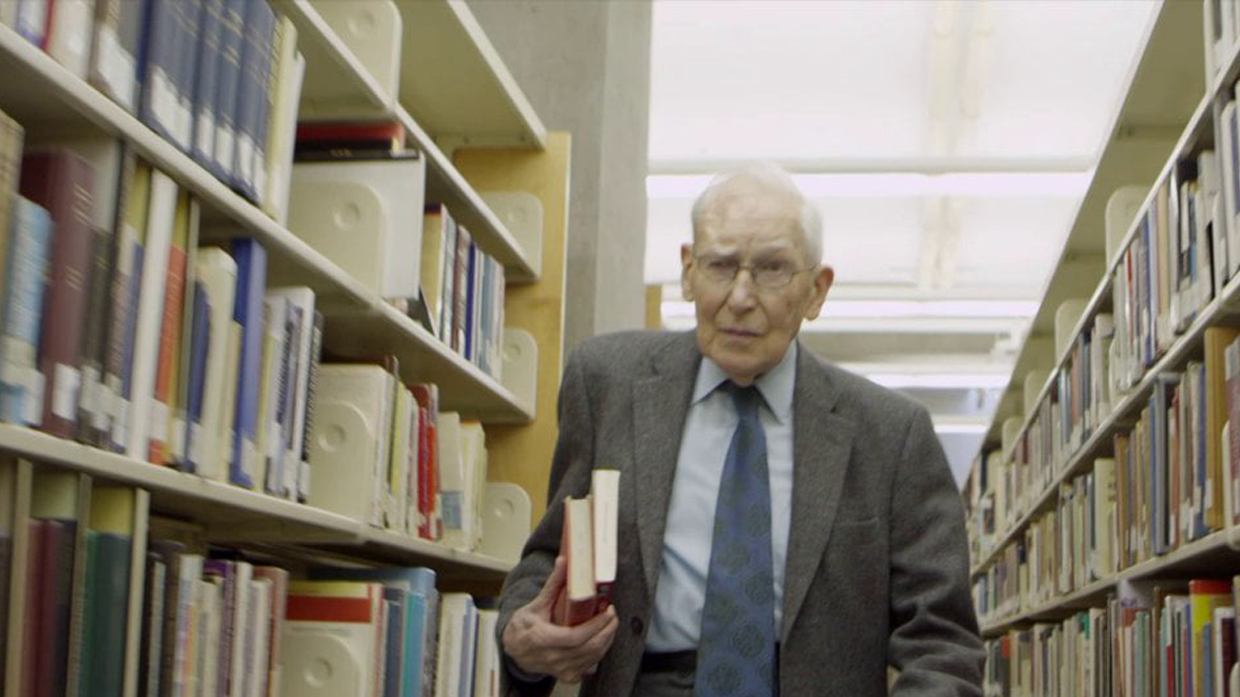

“Packer by name, packer by nature," so the subject of our interview has often quipped, and rightly so. Alister McGrath, recent biographer of J. I. Packer, noted his subject's "remarkable ability to deal with complex issues in crisp and concise sentences."

Yet McGrath also notes that his subject is an "unpacker," in that "he has consistently shown himself able and willing to explain, unfold, and apply the riches of the Christian gospel to his readers."

James Packer is most famous for his packing and unpacking in Knowing God (InterVarsity), which brought him to the attention of Americans in 1973 and has now sold nearly 2 million copies. It was, however, already his thirteenth book. Since then he has published another 26, and in each he aims to present, as he puts it, "truth for people."

In addition to writing, he is a working theologian, teaching at Regent College in Vancouver, British Columbia. He is also an assistant rector at St. John's Church Shaughnessy of Vancouver, a congregation of 1,100. He assists in worship, oversees adult education, and preaches from time to time.

Leadership editors Kevin Miller and Marshall Shelley sat down with Dr. Packer and asked how pastors might best communicate the gospel truth to today's culture.

For many, theology is a bad word. Why have you devoted your life to it?

It helps me appreciate the greatness, goodness, and glory of God—lifting up the sheer wonder and size and majesty of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. In the providence of God, the Puritans and Calvin taught me that's what theology is about. The truth I try to grasp and share is truth that enlarges the soul because it tunes into the greatness of God. It generates awe and adoration.

If this is theology, why do so many people find it objectionable or boring?

Too often theology has been taught in a rigidly defensive way: "This stuff you are to believe and share; these are the errors you are to recognize and reject." Simply projecting orthodoxy that way doesn't give much stimulus to the mind because the conclusion is determined before you've asked the question, and devotionally it is barren.

Such an approach shrinks the soul. Focusing on the greatness of God, though, enlarges the soul. Paradoxically, it makes you a greater person by making you a smaller person. It makes you humble. It lowers you in your own estimate. I've always tried to present truth so that it will humble the sinner and exalt the Savior, and so produce a Christian who's of larger stature than one who simply knows orthodoxy and is prepared to recite it on demand.

What does God-exalting theology say to a culture like ours, which aims to exalt the self?

The business of religion, in many circles, has become trying to make people happy. Anything that enlarges my comfort zone is regarded as good, godly, proper, and to be integrated into my religion.

But true theology challenges the presuppositions of North American culture, both secular and churchly, both of which seem to be primarily concerned with the "right to happiness." True theology calls on us to deny the claims of self and exalt God instead.

You don't come across as someone who is confrontational, though.

You don't usually get anywhere with self-absorbed people by throwing a challenge in their face. In-your-face style usually produces an indignant, negative reaction or withdrawal.

Instead, I've tried to infiltrate happiness-oriented minds with the thought that God might be greater than we imagine and might have a different agenda for us.

I build everything on biblical exegesis and application. John Calvin and the Puritans did that. And in preaching and writing, I find an enormous difference between the feel of putting out my own ideas and the feel of simply echoing and enforcing what God has said in his Word. You have liberty and authority when you allow the Bible to talk through you, a liberty and authority you don't have if you're offering your own ideas or cherished notions. By expanding on Scripture, all of which is God-centered material, I challenge self-absorption indirectly all the time.

Does that mean you're opposed to a user-friendly or seeker-oriented approach to ministry?

Insofar as pastors are concerned to communicate with people where they really are, such concern is very good—but not if they tailor the message so as simply to give people what they want, in hope of increasing church attendance. I know of one or two professedly seeker-sensitive churches where nothing gets paraded or taught but the ABCs of the gospel—why an outsider will find the Christian life a happier life and how an outsider becomes a Christian. In those congregations, Christians of some standing and relative maturity are starving because there's nothing provided for them.

Is it legitimate to appeal to non-Christians at the point of their admittedly self-absorbed need—for example, by offering marriage seminars to get them into church?

There's great wisdom in the old adage "Scratch where it itches." The question is what are you going to tell them about the particular problems on their minds. The really good evangelists, like Billy Graham, always say these problems cannot be solved unless the bigger problem of their basic relationship with God is also solved. Rightly they explain: "It's a single package. We can't put your family life straight unless you're prepared to become a new creature in Christ."

In light of verses about the blessedness and abundance of the Christian life, isn't it legitimate to preach that true Christianity is a means to personal fulfillment?

It's legitimate once you've guarded against the mistake that makes it illegitimate. The mistake is to suppose that I should think of myself as the center of the universe, and God as there for my comfort and my convenience—as if God exists merely to bless me. That assumption has to be junked.

We exist for God. God, in his great mercy, has promised that blessedness will accompany discipleship, but it's got to be God first.

Without that, to say that Christianity is the secret of happiness is dangerous. Often evangelists who preach that way leave the wrong impression and confirm the egocentricity of folk, who then try Christianity as a formula for happiness. God is merciful and sometimes there is a real conversion and real regeneration. But even so, that kind of teaching is likely to produce sub-standard saints.

You don't actually help the butterfly emerge from its chrysalis by cutting the chrysalis. If the butterfly doesn't struggle from inside to get out, it comes out as a butterfly that isn't strong enough to fly. People who get into the Christian life without ever being challenged to repent of their egocentricity are, at best, likely to remain stunted Christians. The struggle to change at this point is necessary for health and growth.

Repentance doesn't seem to be a popular theme in preaching these days. Why is that?

It's due to theological neglect. We don't preach it, and people don't understand it because we don't have an awesome, horizon-filling, overwhelming sense of the greatness and holiness and goodness of God.

Thomas Chalmers, a Scottish pastor of the 1800s, spoke of the "expulsive power of a new affection." That's how true repentance is born; that's how lives get transformed. The new affection is grateful love of a God who saved you, of a Christ who died for you. It means the things of this world grow strangely dim. Only a new vision of the purity and greatness and goodness of God has the power to expel selfish affections and so make repentance real.

Is it appropriate to use guilt to motivate people to repent?

We can't help it. When people wake up to the fact that they've been defying and dishonoring God all these years, they'll feel guilt if the Spirit is working in their hearts.

The next question will be "How can I get straight with God?" This means "How can I get rid of my guilt?" That's when we can talk about, to put it theologically, penal substitution: Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures. Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us.

I hear evangelists, especially youth evangelists, say, "People today simply don't respond if you teach guilt and then highlight the Cross as the act of God putting away guilt; they don't think of themselves as guilty." Well, that's our fault because we haven't told them of their guilt. We haven't made them recognize how thoroughly they've been dishonoring and defying God. We've left them on the egocentric happiness track.

Are judgment and hell themes, then, that today's preachers can use?

They need to play a more prominent part in our message than they have in the last half-century. There's been a strong reaction in Christian circles against imaginative presentations of hell, the fire and all of that. But people do need to know that lostness is a fact.

I have struggled with this a bit in writing against conditional immortality, which is the idea that human beings are not built to last forever, that endless existence is a gift that only the born-again receive, and that those who don't qualify for heaven simply get snuffed out. It's a form of annihilationism.

My concept of hell owes more to C. S. Lewis, whose key thought is that what you have chosen to be in this world comes back at you as your eternal destiny; if you have chosen to have your back, rather than your face, to God; if you've chosen to put up the shutters against his grace rather than to receive it, that's how you will spend eternity. Hell is to live in a state apart from God, where all of the good things in this world no longer remain for you. All that remains is to be shut up in yourself.

In Jean Paul Sartre's play No Exit, four people are in a room they can't leave, and they can't get away from one another. What Sartre presents is the ongoing, endless destruction of each person by the others. Though Sartre was an atheist, his nightmare vision of this process makes substantial sense to me as an image of hell.

This all sounds pretty harsh and confrontive. Can you get away with that today?

In my ministry of preaching to existing congregations, I don't find myself up against people who are explicitly and defiantly making their own happiness the center of their concern. If I did, then I would say straight to them what I just said straight to you.

But I try to say strong things gently. An old English phrase captures the essence of my presentational style: "Softly, softly catchee monkey." It is supposedly the wisdom of an Indian servant in the days of British occupation; he was trying to trap a monkey that was making a nuisance of itself, and he knew the way to catch it was to creep up on it.

Someone said that Charles Finney rode people down with a cavalry charge. Well, I'm not Finney. I set traps for sinners; I try to get them to see the truth by helping them think things through with me, so that they see for themselves that the only right way is the God-centered way.

We live in a culture in which people demand choices, in everything from candy bars to churches. How can we speak to people in this frame of mind?

First, the pastor needs to express constantly in one way or another, "Through my ministry, I trust God is going to speak to you, because my business is simply to let God's Word speak its message through me. And we'll study the Bible together on the matters the Bible treats as central. That's what we as a church have covenanted to do. That agenda is non-negotiable."

Then, in the course of preaching, the pastor has to say in some way, "The only real choice we have is whether we're going to listen to God or not. Are we going to allow him to speak what's on his mind, or are we going to make the rules and allow him to address us only on matters of our choosing?"

How do you preach from the Bible to people who may not care what it teaches?

I haven't got a ready-made formula for doing that. All I know is that when people are born again and have a passion to know God and to deepen their relationship with God—just as a chap who's fallen in love has a passion to deepen his relationship with the girl—everything in Scripture then becomes interesting.

I don't know any quick and easy technique of getting people to study the Bible. So I try to preach about the goodness and greatness and glory of God in a way that I hope will generate the passion, but ultimately I can't produce that effect. Only the Holy Spirit can.

What Bible books can be of most practical help for pastors?

The pastoral epistles in the New Testament, certainly, and the Book of Proverbs in the Old Testament.

Billy Graham has read a chapter of Proverbs every day since his ministry started, and it seems to me that he was absolutely right to do that. Almost without exception he's been able to keep his balance and talk sense about anything people have questioned him on.

Charles Finney rode people down with a cavalry charge. Well I'm not Finney. I set traps for sinners; I try to get them to see the truth by helping them think things through with me: the only right way is the God-centered way.

The pastor needs to have all that wisdom of the Proverbs in his mind because a great deal of pastoral guidance is a matter of Christian common sense, following where Proverbs leads.

I'd also add the rest of the Bible's wisdom literature. To echo Oswald Chambers, the Psalms teach you how to pray; Job teaches you how to suffer; the Song of Solomon teaches you how to love; Proverbs teaches you how to live; and Ecclesiastes teaches you how to enjoy. The more the pastor knows about these books—as well as James, the great New Testament wisdom book—the better.

What signals that people have moved from self-absorption to growing maturity?

Maturity was exemplified by the leaders of the church from the first to the nineteenth centuries, people whom I would characterize as "great souled." There was a sense of stature, a sense of bigness about them that was directly related to the quality of their discipleship. It gave them dignity. It gave them poise and a searching insight. It meant that even when others rubbished or even martyred them, they generated respect.

Sometimes, though, they first generated a robust hatred. Richard Baxter, the seventeenth-century Puritan, was a man of stature who was hated. He got under people's skin simply by his poise, passion, and integrity. Just by being a good man, faithfully serving God, he made people feel bad. John Chrysostom is another example, as were Athanasius and Calvin. I could name so many more.

What role does theology play in this maturing?

Theology is food for the hungry soul. What you have in the Bible, very often, is the raw material, the makings of the meal. We who preach and teach in our character as theologians are like cooks, and it's our business to shape the meal. Good theology, when we produce it, will come as a meal for the soul.

Look at Luther, Calvin, Barth, and Augustine—even at someone as seemingly dry as Charles Hodge in his Systematic Theology. Hodge wrote his stuff for the classroom, most of it apologetics. But when he expands on gospel doctrines, he warms up, and it's very good for the soul.

As you scan the near future, what theological issues will pastors increasingly face?

We're going to have to fight much more against religious pluralism, the idea that all religions are on a par, that all religions are ways to God. It will take us also a couple of decades to get out of the swamp of what's called postmodernism, where you have no notion of absolute truth. In the churches, we will have to be constantly speaking against that because God does speak truth.

We also need to recover a true understanding of human life, a sense of the greatness of the soul. We need to recover the awareness that God is more important than we are, that the future life is more important than this one, that happiness is the promise for heaven, that holiness is the priority here in this world, and that nothing in this world is perfect or complete.

That would give people a view of the significance of their lives on a day-to-day basis, which so many at the moment lack.

You have a liberty and authority when you allow the Bible to talk through you, a liberty and authority you don't have if you're offering your own ideas or cherished notions.