Forty years ago my father, Nate Saint, and four other young missionaries (Jim Elliot, Pete Fleming, Ed McCulley, and Roger Youderian) were speared to death while trying to reach the “Auca” Indians in the Amazon jungles of South America. Today, I have a home among these people—properly called Huaorani—and some of the very men who speared my father have become substitute grandfathers to my children.

For various reasons, the Huaorani story has become a favorite missionary tale among evangelicals. But there is more to the story than the death of five fine young missionaries and the evangelization of the tribe by the sister of one of the martyrs. While it doesn’t lend itself to the happily-ever-after tone that makes the simple version so attractive, it should be told since North American Christians continue to send missionaries into other cultures.

If the primary purpose of missionary effort is to plant indigenous Christian churches, our specific goal as missionaries should be to help these emerging churches become (to use the missiologists’ terminology) self-propagating, self-governing, and self-supporting. I would like to examine here to what extent we have helped the Huaorani to achieve these goals after four decades of mission work among them. My hope is that a realistic appraisal of the Huaorani’s present spiritual and social condition will serve as a case study from which to evaluate our mission strategies today.

First, let me say that there is unmistakable evidence among certain Huaorani Christians today of a strong desire not only to follow Christ but to share the gospel with others (self-propagation). I remember an encounter I witnessed between some Huaorani Christians and members of a secular North American tour group who were visiting a Huaorani camp.

There were 34 students in this group, all from the University of Washington and Western Washington University. To reach the Huaorani encampment, the students were transported by jungle bus to the end of a graveled path laid down by an oil company. From there, three Huaorani men led them through the eastern flanks of the Andes Mountains in Ecuador and down into the virgin Amazon basin. Their trek included 14 hours by foot on a jungle trail as well as paddling downriver in large dugout canoes to reach the campsite.

As the students unloaded their bags, I could see they had come to truly respect and enjoy their Huaorani guides. So much so, in fact, that as we settled around a campfire that evening, a student asked me where the “savage Huaorani” were that they had read about in preparation for the trip. Sitting on logs under a star-studded sky and with a chorus of jungle insects singing in the background, I explained that the very people they had been traveling, eating, sleeping, and hunting with were, in fact, these “savages.”

Seeing the students’ looks of disbelief, I suggested they ask some of the Huaorani who were middle-aged or older where their fathers were. One student, taking up the challenge, nodded toward a Huaorani woman. I translated.

“Boto maempo doobae wendapa,” she replied—”He is already dead a long time ago. Having been speared, he died.” Her tone of voice suggested any other cause would have been unusual.

Four more Huaorani around the circle gave similar answers, graphically showing on their own bodies where each victim had been impaled.

“Ask Ompodae,” one student urged another. Several of the young ladies had taken a liking to Ompodae, an unusually warm and affectionate woman who was a wife and a mother of ten.

“My father, too,” she said, the pain of the memory showing in her expression. Then, holding out her arm, she pointed at old Dabo, who was listening to our conversation a couple of feet away. “He killed my father and almost all of the rest of my family, too. Living angry, he speared them all.”

“My God, I was just sitting next to him,” exclaimed one of the young men from the tour group. Another added, “I’ve heard enough about killing.”

But one more Huaorani woman, Dawa, who normally left the conversation to others, spoke up. Pointing to her aging and gentle husband, Kimo, who was sitting by me, she stated, “Hating us, he speared my father, my brothers, and my mother and baby sister whom my mother was nursing in her hammock. He took me and made me his wife.”

Our visitors looked genuinely stunned. “How could she live with the man who murdered her family?” one of the young ladies asked. The students began whispering among themselves, and suddenly I pictured the setting from their perspective. They had gotten themselves in a situation where they couldn’t travel without a guide. They were utterly dependent for their survival on a group of primitive people that had just admitted to being habitual killers.

It occurred to me that they didn’t yet know my relationship to the Huaorani. Dawa had just finished telling how Kimo had killed her family and made her his wife. Now I put my arm around Kimo’s shoulders and informed them, “He killed my father, too.”

Silence. At last, the question on everyone’s mind found a voice: “What changed these people?”

I interpreted the question, and Dawa, Kimo, and other Huaorani began to describe a life where everyone did as they willed. They explained how they threw babies away when they weren’t convenient to care for. They talked about how people begged to be buried alive when they knew they were dying so their spirits wouldn’t wander without solace when freed from their decomposing and unburied bodies.

One of the Huaorani, a gentle and happy woman, told the group how she had strangled her daughter with her own hands to meet the demands of her speared and dying husband, who wanted his children to be buried with him to keep him company. The one son she had refused to kill was the students’ lead guide.

Then they explained to our 34 highly educated young people from the most technologically advanced society in history how they learned from the missionaries that the Man Maker sent his Son to die for people full of hate, fear, and desire for revenge.

“Badly, badly we lived back then,” Dawa said. “Now, walking God’s trail which he has marked for us on paper [the Bible], we live well. All people still die, but if living you follow God’s trail, then dying will lead you to heaven. But only one trail leads there. All other trails lead to where God will never be after death.”

Dawa’s clear explanation had left her audience spellbound. Now she had a question for her listeners.

“Have you heard me well? Which one of you wants to follow God’s trail, living well?”

There was silence again. Then the seed of Dawa’s message landed in the fertile soil of at least one heart as a lone hand raised into the night air. Dawa understood the American student’s gesture and joyously clapped her hands. “Now I see you well,” she said. “Leaving, we will still see each other in God’s place some day.” Then she looked around at the others. “Dying, I will never see you again if you don’t follow God’s trail. Think well on what I have spoken, so that dying, we will live happily together in heaven.”

As I flew out of the jungle a few days later with the tour leader, I asked him what the students had said they liked best about the tour. “Living with the Huaorani and helping in the tasks of their Stone Age lives,” he replied. Then he added: “What made the biggest impression on them, I think, was the realization that Christianity has the ability to change people’s lives. I am not a Christian myself, but I would say this was a radical realization for most of these young people. Until this trip, they saw Christianity as just another code of conduct.”

Looking back, I see I had been privy to a unique event. I had witnessed the twentieth century coming face to face with the Stone Age—and coming up short. In a fleeting but eternal moment, I had seen God’s Great Commission coming full circle. Dawa’s Spirit-led witness to the gospel was living proof that my father’s blood and Aunt Rachel’s lifetime of service had not been given in vain.

Dawa’s story rightfully warms the heart. But how many of the Huaorani today are like Dawa? To what extent is the Huaorani church self-propagating? Self-supporting? Self-governing?

In 1995, at the request of the Huaorani, I returned to live with these people of my youth. This followed the burial of my father’s sister Rachel, who had lived with them from the first peaceful contact in 1958 until she died of cancer in 1994. The harsh reality I encountered as I returned was that the Huaorani church of the midnineties was less functional than it had been in the early sixties when I lived with Aunt Rachel and the tribe as a young teenager.

The root of the problem, I eventually realized, was that insidious disease that has sucked the life out of many Native American tribes and continues to devastate many ethnic communities within North and South America today—dependency. The Huaorani have become dependent on outsiders—especially North American Christians—for education, for medical and dental services, and for radio communications to relay information between their many villages.

Some of the dependency, of course, had been created by oil companies, government agencies, and other special-interest groups that stand to benefit directly from that dependency—the Huaorani can’t very well tell companies to quit exploring for oil while at the same time asking for outboard motors and cash gifts.

Unlike oil companies, however, the church has a great deal to lose from creating dependency. While most missionaries would not consciously foster dependency, I believe the Devil deceives us into creating this state by prompting us to mix into our legitimate desire to help others a small measure of pride and a dose of cultural arrogance.

It happens almost undiscernibly. Those who have worked with the Huaorani know how very difficult it is for sophisticated, hi-tech North Americans to believe that “primitive” people can take over where we leave off in the process of establishing their church. Take medicine, for example. Health care is one of the most effective means of creating credibility and gaining acceptance in frontier areas. Medical work requires communication links between outposts and a clinic site. Patients must be transported to the clinic by airplane in many remote areas. Electrical power must be generated, clean efficient buildings must be built, and the list goes on and on.

Unlike an oil company, the church has a great deal to lose from creating dependency.

Educated and sophisticated outsiders like ourselves find it hard to imagine—much less trust—people like the Huaorani with building clinics, doing dental work, and flying airplanes. Historically, the Huaorani have been hunter-gatherers who lived in thatched-roof houses with dirt floors, hunting wild pigs, turkeys, tapirs, and deer with spears or nine-foot-long blowguns. Most Huaorani maintained houses and gardens in three or more locations, moving among them as dictated by game depletion or the threat of attack from enemies. They had no chiefs, council, or other means of organizing defense of their territory against outsiders or negotiating peace with each other. In fact, outsiders were not their greatest concern; killing within the tribe was so rampant that they were on the verge of annihilating themselves.

The gospel and the people who brought it gave the Huaorani reason to quit killing outsiders and each other, and in 40 years the tribe has nearly tripled in size (today there are around 1,500). From the beginning, there were signs the Huaorani had accepted for themselves the task of evangelism, and many from the older generation were converted by the witness of their peers. But the younger generation has not understood the perpetual fear and hate that dominated their parents’ and grandparents’ lives. Today only a handful of the younger generation demonstrates an abiding faith in the God and message of peace that so radically changed their parents’ lives.

What has blunted this initial Huaorani desire for winning and discipling their own? I believe it was a failure as missionaries to help the Huaorani church become self-governing. Here, too, the Huaorani had demonstrated early signs of leadership, in spite of the fact that “organizing” and “governing” are totally new concepts to their culture. When I was a teenager, one of the Huaorani friends that I was baptized with led some other young boys in killing a witch doctor’s son. The believers knew that this was wrong and that Inihua needed to be punished. One of the older believers and the father of one of Inihua’s accomplices suggested that the guilty ones should be killed. Others said that, as Christians, they shouldn’t kill anymore, even for punishment.

At last they decided they would pray and ask God himself to punish Inihua. Within days, Inihua, a healthy young man, fell on the ground in front of witnesses, convulsed, and died. While not a typical North American leadership approach (or result), it demonstrated a kind of leadership that was both culturally and spiritually fitting for the Huaorani church.

One of the specific mistakes that we have made, I believe, has been to allow believers from the outside, who have never lived with the Huaorani and who don’t understand their culture, to exert a great deal of influence over the Huaorani church. As innocuous as special Bible conferences and classes may sound, the presence of the outside leaders and teachers who conducted these conferences over the years (and still do) served to undermine the fragile belief among the Huaorani believers that they could govern their own church and teach their own people. (I’ve seen even the smallest gestures of kindness undermine responsible leadership. A Huaorani father and lifelong friend of mine asked me why outsiders give his kids sweets at the school. “Now my children won’t drink their banana drink at home. Scolding their mother, they just say, we want cookies like they give us at school.”)

Lacking self-leadership and facing the loss of their old way of life, the Huaorani have been left poor both materially and spiritually. And sadly, virtually no effort was made by the missionaries over the last four decades to help the Huaorani establish a viable economy from which they could financially support their church, their families, or God’s commission to reach their own people.

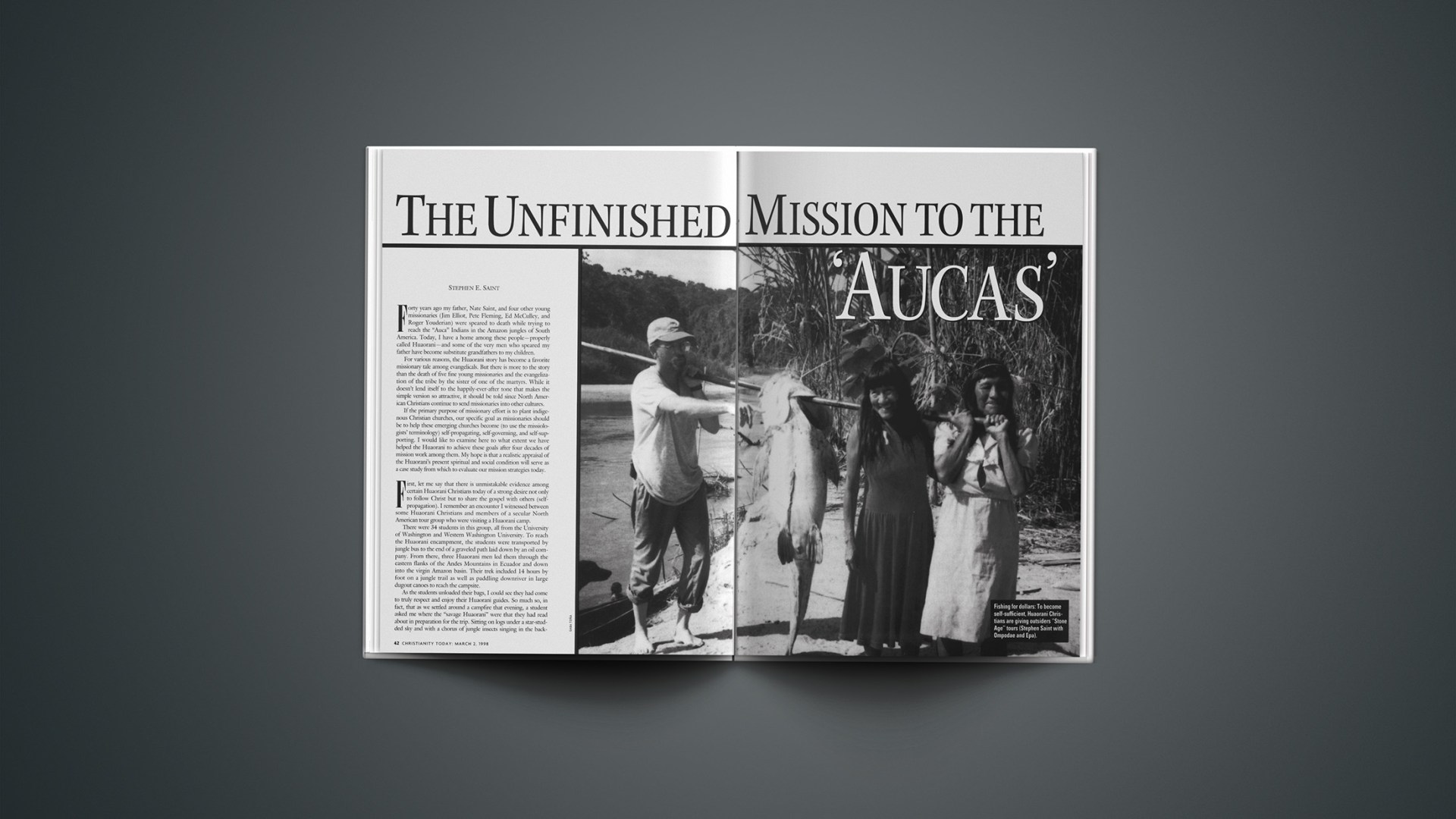

The Huaorani believers are now in the midst of an experiment at becoming self-supporting. In just two-and-a-half years they have built and are running their own dental clinic, pharmacy, trading post, and school. As they drill and fill their own people’s teeth, they share God’s message with them. They are hosting tours of outsiders (hence, the college students from Washington), who pay to visit these “Stone Age” people. Recently, the Huaorani have asked me to help them build and learn to operate their own aircraft, which they see as critical to their long-term independence as a church and as a people.

My contribution has been to cheer them on and to convince them from the Bible that this is God’s will. I have also played the thankless task of challenging foreigners who seem bent on perpetuating “missions” here.

Will it work in the long run? I am convinced it can. So are the Huaorani. I believe that this is the tribe’s only spiritual and economic hope. Outsiders will never get the job done. Nor should they, for we have no business doing what the Huaorani are capable of doing themselves. We must limit our involvement to helping them in the areas they are not yet able to oversee, making every effort to help them become self-sufficient in those areas as quickly as possible.

Christ said that we should “make disciples of all men, teaching them to observe all” that he had commanded us to observe. Faithful missionaries such as Cathy Peek, Rosie Jung, Pat Kelly, and Aunt Rachel gave the Huaorani the New Testament in their own language. This is a fundamental building block for establishing any church. I am excited that the Huaorani have begun to see themselves as true participants in this Great Commission. I pray that we North American Christians, too, will learn to view them—and the others we are reaching out to—in the same way. It is, after all, the gospel way.

Steve Saint and his family maintain a state-side base in Ocala, Florida. For information on tours to the Huaorani, call (352) 694-1998.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.