If Billy Graham is the paragon of evangelical Christianity in America, then Howard Owen Jones is the “Jackie Robinson” of American evangelicalism. Jones has learned that there is a mixed blessing that comes with being the first African American to realize some key achievement in this nation. On the one hand, it is a high honor to overcome a barrier that has long kept blacks on an unequal footing with whites. But there is also the pain of living with the often unfriendly fallout of being a pioneer in the fragile chronicle of racial progress in America.

“It’s an awareness that you’re a living test, a human experiment,” the evangelist explains. “It’s knowing that your every word, your every action, has the potential to either make or break the hopes of your race.”

Jackie Robinson knew this angst when he became the first African American to break the color barrier in major-league baseball in 1947. Martin Luther King, Jr., felt it when he led the American civil-rights movement in the sixties. And Howard Jones experienced it when, in 1957, he became the first black preacher to join evangelist Billy Graham’s crusade team.

Last year marked the fortieth anniversary of Jones’s important breakthrough. It did not receive the same media fanfare as the 50-year observance of Jackie Robinson’s symbolic accomplishment, but in a day when racial reconciliation was not a buzzword in the Christian lexicon and when Martin Luther King had not yet reached the zenith of his national fame, Jones was going where no black man had gone before.

TO AFRICA AND HARLEM If Howard Jones had had his way 60 years ago, he would not have been the first black preacher to hold rallies in Africa or the first African-American associate to join Graham’s crusade team. “I played clarinet and alto saxophone in dance bands,” he says, “and wanted to become the next big name in jazz music.”

Fortunately for Africa, Graham, and the believing community, Jones’s dreams of swinging with Ellington and Basie were cut short by the bigger plans of God—and the prayers of the young woman who would become his wife.

“Wanda challenged me to examine my life,” says Jones. “She told me, ‘I love you, but I love Christ more. You keep playing, and I’ll keep praying.’ That got my attention.

“She finally won me over,” he says. “She helped me understand that when you give your dreams to the Lord, he’ll multiply them in ways you could have never imagined.”

At 22, newly graduated from Nyack College in New York (the Christian and Missionary Alliance’s oldest school), Jones pastored his first congregation, Bethany Alliance Church on Harlem’s Lower East Side. Not content with in-house services alone, Jones took his preaching “on location,” forming Soldiers for Christ, an evangelistic outreach to teens and others in New York’s inner-city neighborhoods. Along the way, Jones became acquainted with Jack Wyrtzen, a noted New York bandleader-turned-minister, whose Word of Life youth radio broadcast and evangelistic rallies regularly packed venues like Carnegie Hall. It was a friendship that would prove significant later in Jones’s career.

After a fruitful eight-year stint in Harlem, Jones returned to his home turf of Cleveland where he assumed pastoral duties at Smoot Memorial Alliance Church in 1952. It was during this period that the preacher came upon a small advertisement by a radio station in Liberia, West Africa, in Christian Life magazine. “The station was interested in receiving recordings of Negro spirituals produced by black churches,” Jones recalls. According to the ad, the Africans loved Negro spirituals. Jones rallied his church choir and recorded some tunes. He was surprised when, a few weeks later, the radio station responded enthusiastically about the tape.

“They said, ‘We want to put you on prime time with both singing and a short message,’ ” Jones recalls. “They told us we’d be able to reach a good portion of Africa with the program. So, naturally, we were very excited about it.”

Jones and his congregants began sending tapes on a regular basis. After a few weeks they were inundated with mail from Africans who had been converted through the program. “They said it was the first time they had ever heard the voice of an American black man,” he says. “From there, it mushroomed to the point where the radio ministry invited us to come to Africa to preach to the people in person.”

With his church’s blessing, Jones, with his wife, Wanda, embarked on a three-month evangelistic tour of Liberia, Ghana, and Nigeria, becoming the first black clergyman to hold major rallies in Africa.

“When we got over there those people went wild,” recalls Jones. “They beat drums, chanted, and said, ‘Praise the Lord, the big bird has brought our brother and sister from America. We’ve seen the white missionary, but we’ve never seen a black preacher from America.’ “

Throughout the cities and bush countries, people turned out by the thousands, some walking as far as 40 miles to get to the meetings. “For too long,” says Jones, “white evangelicals carried an ill-conceived notion that Africans would not respond to black American missionaries. We helped change that perception.”

THE LETTER “The last thing I was expecting when we returned from Africa in 1957 was a letter from Billy Graham,” says Jones. “But a month after we got back, there it was.”

Graham, who was then in the early weeks of his massive 68-day crusade at New York’s Madison Square Garden, had had breakfast one morning with Jack Wyrtzen, with whom he discussed his dilemma: The minority turnout had been dreadful, and Graham, who had pledged never to conduct another segregated crusade following the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling banning segregation in public schools, wanted to practice the social justice he had been espousing. The evangelist had already integrated his team with Akbar Abdul-Haqq, a gifted preacher from India, but he wanted to add a black team member to his lineup.

Wyrtzen recommended Jones.

Jones remembers his first meeting with Graham: “Billy jumped up and grabbed me and said, ‘God bless you, my friend. I’ve heard a lot about you and your ministry, and I want you to come be with us for a few weeks at the New York crusade.’ I said, ‘I don’t know, Billy. I’ve already been away from my church for three months.’ I was afraid that if I asked for any more time off they’d kick me out.”

Graham persisted and even offered to send a letter to Jones’s parishioners, requesting their pastor’s services. It was all that was needed. In fact, Jones’s congregation was delighted that their pastor was being “borrowed” by the world’s most famous preacher.

“It was a tough decision,” says Jones. “As a pastor you want to be there for your people. But as an evangelist I had to be open to going wherever God called me. I knew I would eventually have to make a decision for one or the other.”

THE EVANGELISM EXPERIMENT When Jackie Robinson began baseball’s historic “experiment” in racial integration in America, he was well aware of the inevitable consequences from unsympathetic whites: vicious racial put-downs, death threats, hate mail, “wild pitches” aimed at his head, fellow players refusing to shake his hand. Through it all, Robinson’s assignment was to turn the other cheek.

Jones faced a similar challenge once word hit the street regarding his addition to Graham’s New York crew. Immediately, Graham began getting “static” from some New York clergymen, says Jones. “You should not have that Negro on your team,” came the impassioned warnings. “You’re going to ruin your ministry by adding minorities.” “If you have him, we’re going to stop supporting you.”

Graham persevered. “There was never any hesitation on Billy’s part,” says Jones. “He had dug the trench, you might say, and he was going through. He knew it was what God was calling him to.”

Graham looked to Jones for advice on boosting minority turnout at the New York crusade, and Jones gave him the hard truth. “If they’re not coming to you, you have to go where they are,” Jones explained to Graham. “Billy,” Jones continued, “you need to go to Harlem.”

White Christians warned that it was too dangerous—”Those savages up there will kill you!”—but Graham made plans to hold a rally in Harlem. “The funny thing is,” says Jones today, “some of those whites who were saying ‘Don’t go to Harlem’ were members of evangelical churches that were sending white missionaries to Africa. They weren’t afraid of the blacks over there.”

Using his New York contacts, Jones spearheaded a successful rally of more than 8,000 people in Harlem, followed the next week by a similar event in Brooklyn, where more than 10,000 blacks and other minorities came out to hear Graham. Jones’s plan worked. The events resulted in increased black attendance at the crusade. U.S. News & World Report estimated that by the conclusion of the New York campaign, blacks composed 20 percent of the 18,000 people who attended the crusade each evening.

Jones was happy to see God bless the crusade with an increased minority turnout, but he remembers that period as being one of the hardest times of his life. “I was overwhelmed with a sense of loneliness,” he says. “The stares, the people muttering under their voices. In the crusade there were nights when it was palpable.”

With his wife and kids back in Cleveland, Jones was often the only African American around during the long days prior to the evening meetings. And the evenings were not much better. “I remember sitting on the crusade platform on various occasions with empty seats next to me because some white crusade participants had decided to sit on the other side of the stage.”

At other times, Jones would go down to counsel new believers during the altar calls only to see white counselors move in the other direction. One night he remembers hearing two white pastors seated behind him murmuring: “How did he get up here?” one of them asked. The other replied, “That’s Graham’s new associate.”

Jones sported a steely demeanor while in public, but once alone the mask came down. “There were nights when I went back to my hotel room and literally wept before God and told him, ‘Lord, I can’t take this pressure,’ ” he says. “I felt like telling Billy that it was too much. But I knew his heart and I knew the heart of the team, and God gave me the strength to endure.”

A month after the New York crusade, Graham approached Jones about joining his staff full-time. “It was an honor,” Jones says, “but I was torn. I returned to the church in Cleveland, but in my heart there was a restlessness that God was calling me as a full-time evangelist.

“We stayed at the church for another year,” he says. “But during that year, we prayed and fasted for a clear signal from God. And finally we felt led to accept Billy’s invitation.”

Some ten years later, he would need to summon that special strength again when he was attacked by critics from the other side—advocates of the Black Power movement who felt Jones was a “sell-out” or in the “hip pocket of the white man,” and that Graham was too soft on the issues of race and social activism.

“I lost a lot of my black friends who thought I should leave Billy,” Jones recalls. “But I knew the right thing was to stay. The people who accuse Billy of not being vocal enough against racism and other social issues have not seen what goes on behind the scenes. They do not know that man’s heart.”

Jones served as an associate with the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA) for more than 35 years, until his retirement in 1994. During that time he participated in additional evangelistic campaigns to Africa and many other nations, helped bring Canadian evangelist Ralph Bell on board as Graham’s second black associate, and he was instrumental in launching various humanitarian initiatives on behalf of the BGEA, such as raising $80,000 for famine-stricken West Africa in 1975. Still, according to Bell, Jones’s efforts to promote social activism were not always greeted with enthusiasm by the BGEA. “Like any organization, there were those who were all for it, and those who had problems with anything besides traditional outreach,” Bell explains. “Howard played a strong role in showing Billy the importance of meeting physical needs as well as the spiritual.”

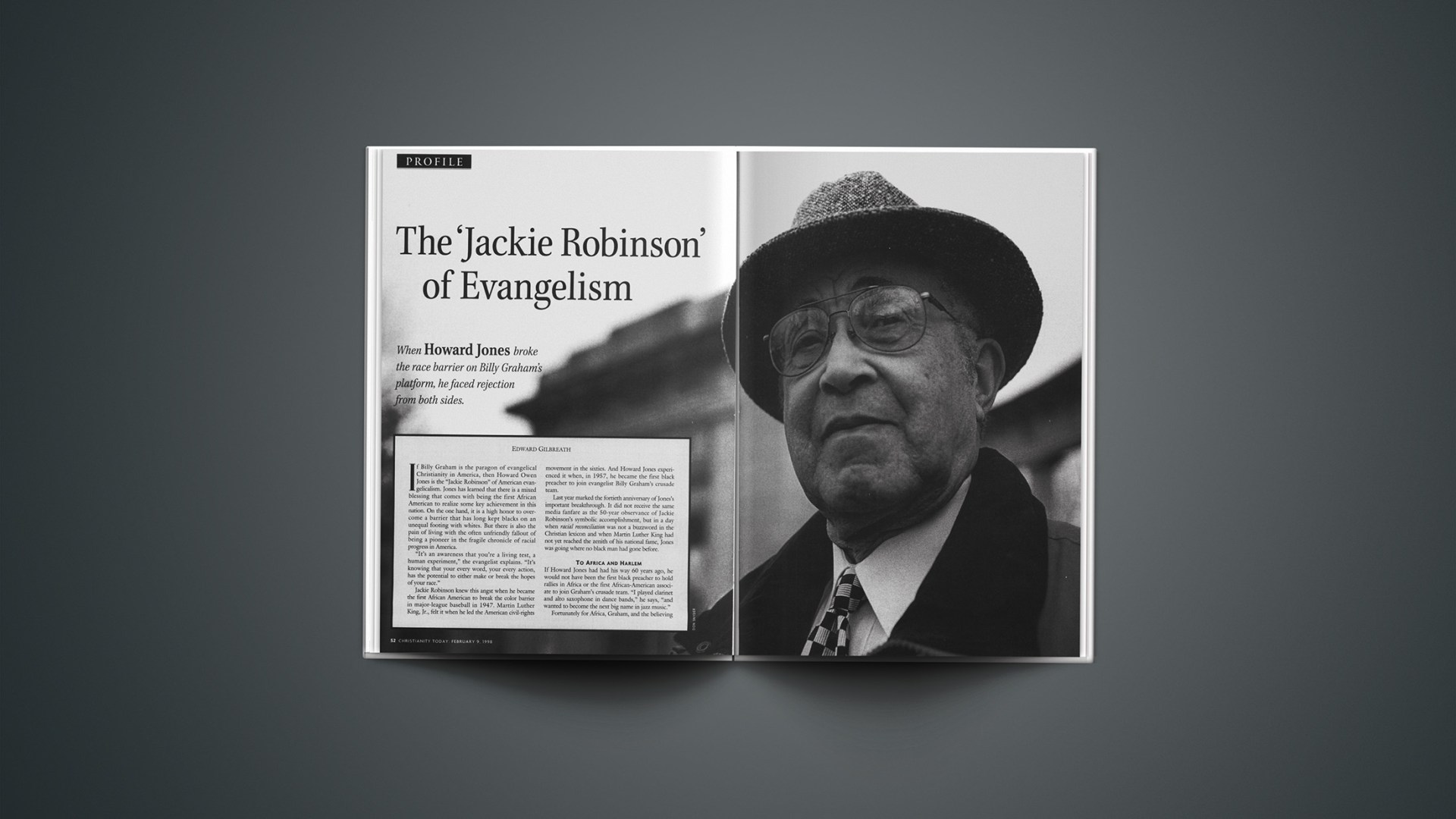

TOWARD SPIRITUAL RENEWAL At 76, Jones is a lanky, yet solid figure. Old recordings reveal his straightforward, though passionate preaching—he did not embrace the “whooping” style of many African-American preachers. His passion is also conveyed in his commitment to go wherever the Lord led him. These days, Jones is a father of five and grandfather of six, living in a modest, two-story home in Oberlin, Ohio.

Though retired, Jones’s current concern is what he calls the “troubling” condition of the African-American church. “Too many churches today still are not delivering the goods—the whole gospel,” Jones says. “And it bothers me, because I see Muslim groups coming in and taking our young men because we’ve been unable to show them the true power of Christ’s gospel.”

Jones’s most recent book (coauthored with Wanda), Heritage and Hope: The Legacy and Future of the Black Family in America (Victor Books, 1992), addresses his concern over the African-American community “entrenched in cycles of despair and hopelessness.”

“Some folks may be tired of hearing those depressing statistics repeated over and over,” Jones says, “but it’s an important reminder to me of how far we’ve moved away from God and how racism and oppression have left a scar on the black family. But through Christ, we have a hope of ending the cycle of these types of numbers.”

In addition to his work at the BGEA, Jones served as the first president of the National Black Evangelical Association (NBEA). Recently he became the first African American named to the National Religious Broadcasters’ Hall of Fame. Aaron Hamlin, president and executive director of the NBEA, calls Jones “a key figure in the maturation of the evangelical church. Reverend Jones has both encouraged the growth of black ministers and ministries and facilitated relationships between black and white organizations.”

“Things have definitely improved from the days when I first joined Billy,” Jones says. “But, at the same time, it’s a bit disheartening to realize that many of the prejudiced attitudes that thrived back then are still very much alive in a more covert way.

“The greatest need for Christians today is a moral and spiritual awakening,” he says, “but I don’t think we’re going to see an outpouring of the Holy Spirit like we need until the church comes to grips with its race problem, because Jesus said, ‘By this shall all men know that you are my disciples—because you love one another.’ “

In pursuit of that Christian ideal, Howard Jones has seen it all—both the triumph of progress and the pain of prejudice.

“But the promise of being a whole church one day is worth the pain,” says Jones. “It’s worth the pain.”

Edward Gilbreath is associate editor of New Man magazine.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.