In this series

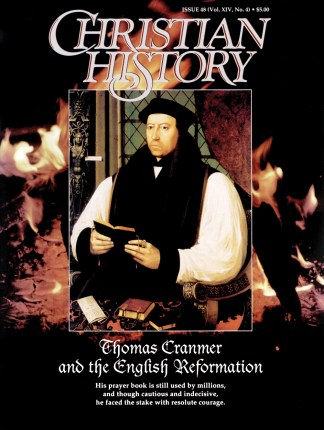

As archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer played a key role in the English Reformation. When he first heard about his appointment, though, he balked. Away in Europe, he delayed his return to England for seven weeks, hoping Henry would get impatient and appoint someone else.

Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer, the liturgy of the Anglican church (including the Episcopal church), is known for its memorable expression of Christian theology. But Cranmer was only a modestly talented student, ranking thirty-second in his Cambridge class of 42.

Before he was a priest, Cranmer married, but his wife died in childbirth within a year. After becoming ordained as a priest, Cranmer married again, and he kept the marriage a secret for his first 14 years as archbishop because priestly marriage was forbidden.

Some have accused Cranmer of making a deal with Henry: if appointed archbishop of Canterbury, he would resolve Henry’s “privy question”—his need to legally divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn. Long before his appointment, Cranmer believed Henry’s divorce was justified and had encouraged Henry to gain wider approval for it.

The divorce question was debated in Europe’s major universities, and many theologians had opinions about it. The most unusual may have been Martin Luther’s: “I would rather permit the king to marry still another woman and to have, according to the examples of the patriarchs and kings [of Scripture], two women or queens at the same time.”

Henry VIII was not a Protestant, even after his break from Rome. He believed in transubstantiation, priestly celibacy, and other Catholic doctrines. He wanted Catholicism without the pope. Thus he had both Protestants and Roman Catholics executed in his reign—anyone who would not acknowledge him as supreme head of his church.

In the early 1530s, William Tyndale was persecuted by Henry VIII and executed in exile for, among other things, translating the Bible into English. Two years later, by Henry VIII’s orders, an English Bible was placed in every English church, and everyone was encouraged to read it; the earliest edition of this required Bible contained large portions of Tyndale’s translation.

By 1540, however, Henry forbade anyone under the rank of gentleman or merchant to read large portions of the Bible. Henry believed the Devil was causing a sinister understanding of Scripture to enter people’s hearts.

Cranmer was almost fanatical in his obedience to his sovereign, whom he believed was the divinely appointed head of the church. For example, to satisfy Henry, he ruled that Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves would be lawful. But when Henry wanted a divorce six months later, Cranmer approved it on the grounds that the original marriage was unlawful.

Henry VIII liked his archbishop and removed him from harm. When Cranmer’s enemies wanted Cranmer tried for treason, Henry appointed Cranmer the head of the commission to investigate the charges.

In composing his Book of Common Prayer, Cranmer took five medieval liturgical tomes and reduced them into a single volume. His liturgy is still used by the Church of England today, nearly 450 years later.

When Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer was required to be used in churches across England, thousands rebelled, some violently. But the rebels were disturbed not because of the service’s Protestant theology but because it was no longer in Latin but in English.

In the weeks before his execution, Cranmer recanted his Protestantism several times. On the day he was executed, though, he recanted once more—“As for the pope, I refuse him as Christ’s enemy and Antichrist, with all his false doctrines”—and so died a Reformation martyr.

At first, Anglicanism flourished in England and its English-speaking colonies (including the Episcopal church in the U.S.). The United Kingdom still has over half of the world’s 51 million Anglicans, but today more Anglicans worship in Africa than in the U.S., Canada, and Australia combined.

Copyright © 1995 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.