How five women leaders are reinventing the pro-life movement.

Many Americans did not grasp the severity of the Vietnam War until television news brought it into their living rooms. Flaming village huts and countless stretchers of broken young men: such images distilled the war for the masses.

Around the time the U.S. pulled out of Vietnam, another war erupted. The 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision sparked a civil war over abortion that has been escalating ever since. Like Vietnam, it is a struggle often reduced to pictures on the nightly news: scuffles at abortion-clinic doors, grim placards, handcuffed protesters loaded into police vans.

Last year the murder of abortion doctor David Gunn intensified the conflict. The broadcast media put angry pro-life extremists on everything from network news broadcasts to Donahue. To the casual observer, it might have appeared that these defenders of violence spoke for the pro-life movement.

Not only are defenders of the preborn said to promote violence, they are also accused of being anti-women. “Four, six, eight, ten,” the pro-choicers at the barricades shout at pro-life activists, “why are all your leaders men?”

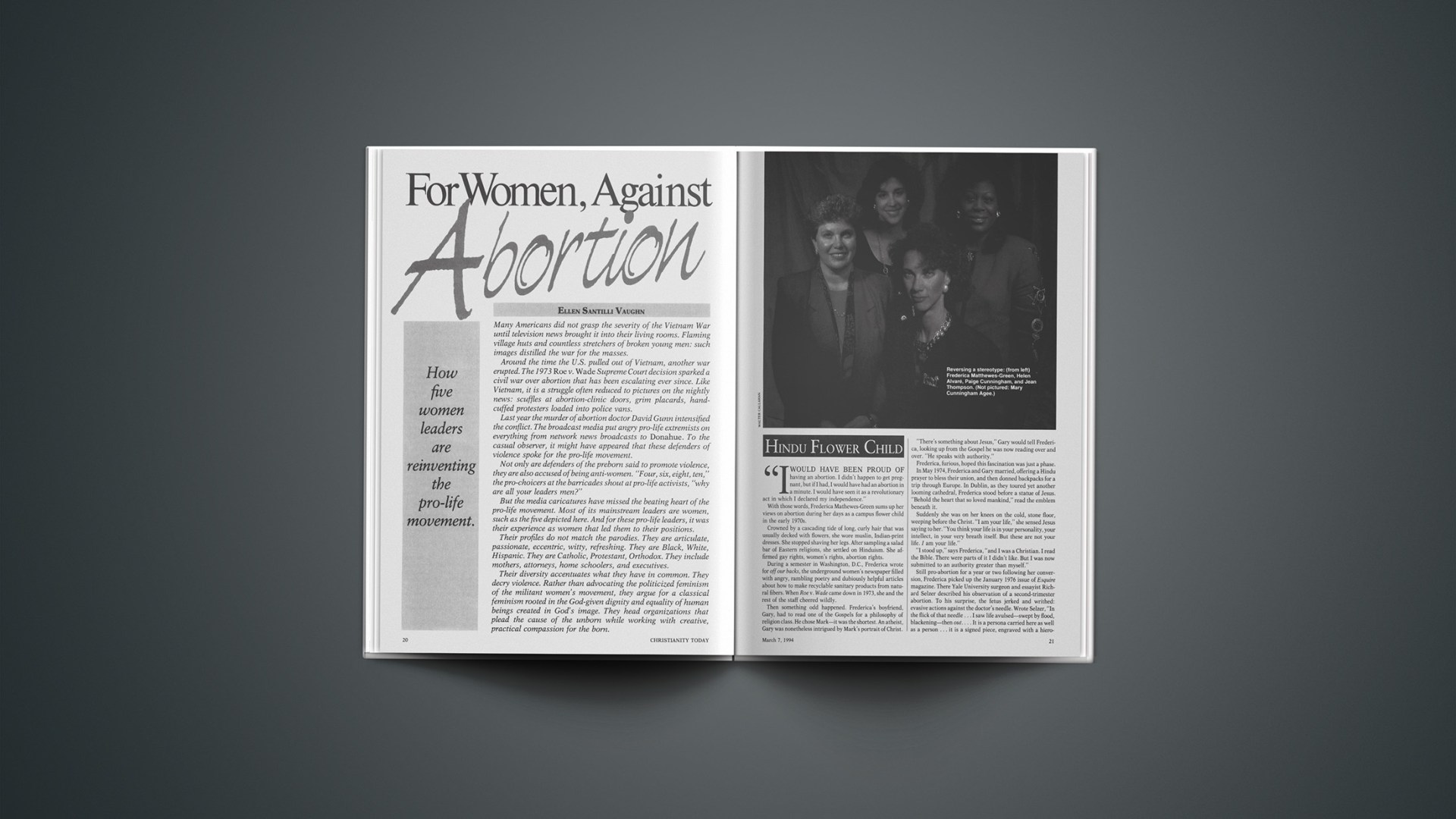

But the media caricatures have missed the beating heart of the pro-life movement. Most of its mainstream leaders are women, such as the five depicted here. And for these pro-life leaders, it was their experience as women that led them to their positions.

Their profiles do not match the parodies. They are articulate, passionate, eccentric, witty, refreshing. They are Black, White, Hispanic. They are Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox. They include mothers, attorneys, home schoolers, and executives.

Their diversity accentuates what they have in common. They decry violence. Rather than advocating the politicized feminism of the militant women’s movement, they argue for a classical feminism rooted in the God-given dignity and equality of human beings created in God’s image. They head organizations that plead the cause of the unborn while working with creative, practical compassion for the born.

HINDU FLOWER CHILD

“I would have been proud of having an abortion. I didn’t happen to get pregnant, but if I had, I would have had an abortion in a minute. I would have seen it as a revolutionary act in which I declared my independence.”

With those words, Frederica Mathewes-Green sums up her views on abortion during her days as a campus flower child in the early 1970s.

Crowned by a cascading tide of long, curly hair that was usually decked with flowers, she wore muslin, Indian-print dresses. She stopped shaving her legs. After sampling a salad bar of Eastern religions, she settled on Hinduism. She affirmed gay rights, women’s rights, abortion rights.

During a semester in Washington, D.C., Frederica wrote for off our backs, the underground women’s newspaper filled with angry, rambling poetry and dubiously helpful articles about how to make recyclable sanitary products from natural fibers. When Roe v. Wade came down in 1973, she and the rest of the staff cheered wildly.

Then something odd happened. Frederica’s boyfriend, Gary, had to read one of the Gospels for a philosophy of religion class. He chose Mark—it was the shortest. An atheist, Gary was nonetheless intrigued by Mark’s portrait of Christ.

“There’s something about Jesus,” Gary would tell Frederica, looking up from the Gospel he was now reading over and over. “He speaks with authority.”

Frederica, furious, hoped this fascination was just a phase.

In May 1974, Frederica and Gary married, offering a Hindu prayer to bless their union, and then donned backpacks for a trip through Europe. In Dublin, as they toured yet another looming cathedral, Frederica stood before a statue of Jesus. “Behold the heart that so loved mankind,” read the emblem beneath it.

Suddenly she was on her knees on the cold, stone floor, weeping before the Christ. “I am your life,” she sensed Jesus saying to her. “You think your life is in your personality, your intellect, in your very breath itself. But these are not your life. I am your life.”

“I stood up,” says Frederica, “and I was a Christian. I read the Bible. There were parts of it I didn’t like. But I was now submitted to an authority greater than myself.”

Still pro-abortion for a year or two following her conversion, Frederica picked up the January 1976 issue of Esquire magazine. There Yale University surgeon and essayist Richard Selzer described his observation of a second-trimester abortion. To his surprise, the fetus jerked and writhed: evasive actions against the doctor’s needle. Wrote Selzer, “In the flick of that needle … I saw life avulsed—swept by flood, blackening—then out.… It is a persona carried here as well as a person … it is a signed piece, engraved with a hieroglyph of human genes. I did not think this until I saw. The flick. The fending off.”

“At that point I wouldn’t have yet been reading magazines like CHRISTIANITY TODAY,” says Frederica. “But this article in Esquire, of all places, upset my grid for the world. I had never thought about there being a real life in the womb. The article changed my mind.”

Today Frederica is director of Real Choices, a research project of the National Women’s Coalition for Life, a coalition of 15 organizations whose combined membership includes more than 1.8 million women.

Frederica’s research on postabortive women shows that most women facing a crisis pregnancy do not truly want to get an abortion. A woman “wants an abortion as an animal, caught in a trap, wants to gnaw off its own leg,” she says. So Real Choices aims to identify the factors that make an unplanned pregnancy feel so desperate—and then to develop networks of people who can help women over these hurdles so their desperation will not result in the deaths of unborn children.

Former flower-child Frederica’s Nefertiti tresses are now cropped short; her “women’s power” jeans patches and earth shoes have been replaced with a briefcase with a Bible in it and navy-blue high heels. Gary, whose conversion began with Mark’s Gospel, is now an Orthodox priest. Their home in Baltimore is a haven of happy, holy confusion, populated by three cats, one Dalmatian, and three children.

“My heart,” she says, “is broken for my sisters in the pro-choice movement.” Frederica works hard to build relationships and share her research findings with those who are pro-choice. “I was there once, and I want to throw them a lifeline. My heart yearns for the women who are damaged, deceived, duped; the women whose arms will always be empty. Abortion leaves only the broken body of the child, and the broken heart of the woman.”

SINGING THE BLUES AT MOTEL 6

She holds “one of the most visible—and controversial—positions in American Catholicism,” the St. Petersburg Times reported about Helen Alvaré. As spokesperson for the National Council of Catholic Bishops, Helen heads the Catholic church’s public-relations campaign to present persuasively its pro-life position, and she does so with passion and panache, traveling the nation a hundred days a year.

But on any one of those hundred nights, look in that room with the light on in a Motel 6 in Muskegee or a Hyatt in Helena, and you’ll see another side of Helen Alvaré: barefoot, sitting on the side of the bed, playing the guitar, and singing the blues for all she is worth.

Helen has discovered that the torrent of words she expends on debate during the day does not abate when she gets to her room at night. So she had a miniature guitar built, and she packs it on every trip. During those evenings, she belts out the blues, clearing her mind for the next day’s debates, which she relishes.

A summa cum laude graduate of Villanova University, she received her law degree from Cornell University when she was 23, has a master’s degree in systematic theology from Catholic University, and is working on her doctorate. She has worked as a trial lawyer and has written friend-of-the-court briefs for the U.S. Catholic Conference on a variety of cases.

From a Catholic Cuban family, Helen attended her first pro-life rally in Washington when she was 13. She realized she was outspoken, “even a little pushy,” and that that pushiness could be used for others, particularly those who could not speak for themselves.

“Arguing on behalf of the underdog is its own reward,” says Helen, “but I am also compelled by the incredible cogency of the pro-life arguments. Then as I read abortion literature I am struck by the absolute inadequacy of their arguments.”

Opponents do not let that stop them. Helen cannot count the number of times pro-choice advocates have dismissed the Catholic church’s position on abortion because, after all, the church did not acknowledge that Galileo was right.

Helen frames the issue in terms of human rights. “We are confronted with human life. We can do no less than afford that life the dignity and respect that all human lives deserve. We can’t discriminate on things like size, development, lack of legal protection, lack of physical abilities. All must be treated with dignity, simply because they are human.”

The same arguments support true feminism, she says. Women are equal because they are human. Founding feminists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were staunchly pro-life; the abortion ethic utterly violates the feminist ideals of nonviolence and inclusiveness.

Helen’s articulate, persuasive point of view often surprises those who expect from the Catholic church dusty theological statements emanating from a graying cleric. She also has experienced the media’s preference for pro-lifers who fit their caricature. Several times she has prepared for national television interviews, only to be replaced at the last minute by others who espouse violence for the sake of the pro-life cause—a position that Helen unequivocally condemns.

In spite of such frustrations of life on the road, however, Helen’s travels have led her to believe that people are weary of the mindset of absolute license birthed by the abortion ethic. “People are looking for real freedom,” she says. “Freedom involves giving yourself over to God and being enabled to do what you ought to do, not whatever you want to do.” It entails discipline.

That discipline is not unlike the disciplines of art and music. It demands daily repetitions of the fundamentals. And that is why Helen Alvaré continues to practice the guitar, doing all those finger exercises in the Motel 6, so she can sing the blues with glorious abandon.

SAVING BLACK BABIES

Jean thompson lay on the examining table, her heart beating fast. She and her husband, James, had waited long and prayerfully for a child. But now, 11 weeks into her pregnancy, she was bleeding heavily. The doctor was telling her she needed a D and C.

“Doctor,” said Jean, “if you scrape out the womb, what will that do to the baby?”

“Baby?” the doctor responded brusquely. “What baby?” “You know I’m pregnant,” Jean said softly.

“You’ve passed tissue,” the doctor said. “You’ll have to have a D and C.”

Jean paused. “But the nurse said my cervix is closed,” she said hesitantly.

“Then we’ll just have to open it,” he said.

“You don’t understand,” she said. “My husband and I have been waiting 12 years for this baby. Isn’t there some other kind of test I could take to make sure.…”

“No, you don’t understand,” said the doctor angrily. “You are bleeding, your life is at stake, you need to have a D and C immediately.”

Jean said she would have to see another doctor. She signed papers absolving the doctor of responsibility. Her husband helped her walk to the car, and they saw another doctor.

After a physical examination, he did a sonogram—and there was her baby, alive and well. The doctor looked up from the flickering screen. “If you had let them do a D and C,” he said, “they would have scraped out a live baby.”

Today Jean Thompson relates that story with a mixture of tears and tenacity from her office at the Harvest Church International in Mount Ranier, Maryland. Jean and James copastor the 2,000-member church, and Jean is president of the International Black Women’s Network, an association that equips African-American women with job skills, community opportunities, and other resources. It is also a member organization of the National Women’s Coalition for Life. A large, framed portrait on the wall behind her shows Jean, James, and Sherah, a small, grinning girl in a white dress: their only child.

Narrowly avoiding an unwanted abortion has sensitized Jean to the insidious targeting of African Americans by abortion providers.

“Abortion is deadly in the Black community,” she says. “It’s not a friend.” Though Blacks make up only about 12 percent of the U.S. population, they account for 43 percent of abortions performed in this country. Seventy percent of Planned Parenthood’s clinics are in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. This presence has not brought about a decrease in the number of pregnancies, but it has brought an increase in the number of abortions; for every three Black babies born, two are aborted.

Jean hears from the teenagers who attend her church how Planned Parenthood pressures them. Representatives regularly visit their schools, extolling a trinity of condoms, contraception, and abortion. “Pastor Jean,” one young girl told her, “they talk to us like we’re cats and dogs, like we just gotta go out there and do it, and if we don’t, we’ll go crazy.”

“The pressure comes not so much from other young people,” says Jean, “but from these organizations. They are encouraging promiscuity, which leads to pregnancy, which leads to abortion.”

Jean’s gentle speaking voice and attractive composure—she is a former Miss Black Virginia—do not soften her message about abortion. Invited in 1992 to appear on a Linda Ellerbee television debate on the issue, she carried a large handbag onto the set. When her turn came to speak, she reached into her bag, pulled out a thick, white noose, and placed it around her own neck. “Would you call this freedom of choice?” she asked the astonished panel. “This is what abortion does. It is a new means of Black lynching.”

Jean is careful to say that Christians must love and pray for those on the other side of the issue, but she minces no words in speaking up for the unborn. “Sometimes Christians say, ‘You can’t come on religiously.’ But I believe that Christians have not been articulating the Word of God enough. God says that the unborn person is a life. We must choose life.”

ADDING JUSTICE TO COMPASSION

It is july 23, 1993. the unblinking eye of C-SPAN focuses on the long, narrow table before the massive pulpit of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Witnesses are preparing to testify in opposition to President Clinton’s nomination of Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Leading the testimony is a tall young woman who speaks with surety. “My name is Paige Comstock Cunningham,” she begins. “I am an attorney, a graduate of Northwestern University Law School, a wife, and a proud mother of three children. It is likely that I have reaped, in my own professional career, from the seeds sown by Judge Ginsburg in her efforts to abolish sex discrimination.

“I am also the president of Americans United for Life [AUL], the legal arm of the pro-life movement.… [We are deeply disturbed by] Judge Ginsburg’s attempt to justify the decision in Roe v. Wade on the ground that abortion is somehow necessary for women’s equality.…

“Judge Ginsburg has testified before you that abortion is ‘central to a woman’s dignity.’ … I believe it has actually set the clock back on women’s dignity.… Abortion goes against the core values of feminism: equality, care, nurturing, compassion, inclusion, and nonviolence. If we women, who have only recently gained electoral and political voice, do not stand up for the voiceless and powerless, who will?”

The pleas of Paige Cunningham and others who testified that day did not stop Judge Ginsburg’s evolution into Justice Ginsburg. But for Paige, they represented an ongoing, dual appeal: first, a call to justice, to concern for the human rights of the voiceless unborn; and second, a call to compassion for the millions of women for whom abortion has not been a means of achieving dignity, but a degrading wound.

On C-SPAN, Paige looked like a coolly competent attorney, a woman whose life is a grid of flight schedules, interviews, and debates, yet who can emerge from an 18-hour day with her composure still intact. Yet Paige’s journey to her appearance before the Judiciary Committee was shaped most profoundly not by professional forces, but by intense personal suffering that has caused her to identify deeply with women who have been wounded by abortion.

Born in Brazil of missionary parents, Paige excelled at excelling. Academics, music, and maturity seemed to come easily. Yet through her stint at Taylor University, then law school at Northwestern, she often felt like an outsider.

That feeling extended to her faith: though she had committed her life to Christ as a young girl, she sensed she was missing an abundant life. She felt a subtle dissonance between the outwardly confident young woman who eventually married, had children, practiced law, and did it all, and the inner person who fought back tides of depression.

Paige maintained the veneer as she practiced law with two Chicago firms, then became associated with AUL, serving in various general-counsel capacities and later as a member of its board of directors. But eventually the multiple stresses burned her out.

Paige attended a three-day Episcopal church retreat; the unconditional love expressed by the laypeople there began to incarnate Christ’s love for her personally. She had known the truth of his love intellectually, but its power had been suppressed by the dark secret she had long hidden: a traumatic violation as a child by someone she trusted.

Some time after the retreat, while on an extended visit with her brother and his family, Paige immersed herself in the nurture of his Dallas-area church. During a small-group meeting, she asked for special prayer.

And then, Paige Cunningham saw in her mind’s eye all her sins upon an altar, with a mighty fire burning them away. She saw herself, a small girl again, timidly looking up at Christ on the cross. Then Jesus came down, flung his strong arms wide, and held her close. And then she knew that he would never let her go.

“For me,” Paige says today, “that was the beginning of deep, real healing.” And she began to feel, welling up from the pool of her own suffering, an intense compassion for women who had been violated, exploited, and hurt, women who had felt not the “empowerment” of “choice,” but chains binding them to make just one choice. And she found, with this new empathy and vulnerability, a paradoxical sense of confidence that propelled her to speak out with passion before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Paige sees her journey to compassion mirrored in the wider pro-life movement. “God is doing a new thing among us,” she says. “The first 20 years since Roe v. Wade have been characterized by justice. We’ve gone to court again and again, seeking to limit abortion. And these efforts must continue.

“But now we must set a pattern of mercy. Women facing crisis pregnancies have seen themselves as a kind of political football. Many have felt that to pro-lifers, they are merely a means to an end. Abortion hurts them, and they must know that we’re on their side. We must love the wrongdoer, without embracing the wrong. With compassion and mercy, we must touch women’s lives, saving not only women, but their babies as well.”

EXECUTIVE FOR THE UNBORN

It begins with her voice. never mind the Phi Beta Kappa key from Wellesley College, the Harvard MBA, the classically trained, logical mind that fueled high-level corporate planning and a controversial rise to the executive suites of the Chase Manhattan Bank, the Bendix Corporation, Joseph E. Seagrams & Sons—all by the time she was 32 years old. Never mind the humanitarian awards, the board of directors positions, the citation as one of the “most influential women in America.” Never mind her New York Times bestseller Powerplay.

No, Mary Cunningham Agee’s voice is the key to her persuasive power, for in it is the perfect merger of style and content: a modulated, seamless method of speech and a compassionate message of Christian love.

That message was shaped long before Mary came to the ivory towers of the Ivy League and the glass towers of corporate boardrooms. It began in a mossy rock garden, when Mary was seven years old, the morning of her First Communion. Decked in a white cotton dress, she sat on a small rock while Father William Nolan—her Uncle Bill—sat on a larger one.

It was a special day, but even happy days had a hole in them for Mary, whose father had abandoned their family a year and a half earlier. Uncle Bill had stood in the gap, but even he could not take her dad’s place. Now he was talking to her quietly about the Lord’s Prayer.

“As he did,” Mary says today, “I suddenly realized that as I prayed, ‘Our Father who art in heaven,’ God was a father to me. I had lost something very precious to me, but that loss made room for grace in my life. I learned that only in suffering and loss can we be prepared to be filled by grace.”

That childhood epiphany stayed with Mary, carried her through professional storms in the early 1980s, and comforted her when she experienced the most painful loss of her life. After marrying William Agee, former CEO of Bendix, now CEO of Morrison Knudsen Corporation, they joyfully anticipated the birth of their first child.

But after seeing her tiny daughter dance on the sonogram screen, Mary suffered a second-trimester miscarriage in January 1984. For months afterward, she stared at the empty nursery, aching within.

As she prayed, she began to think about other women who had lost children, but who were not surrounded by loving support, as Mary was, who had seen no way out of their predicament other than an abortion.

Feeling called to act on such women’s behalf, Mary called ten abortion clinics around the country. In each call, she asked the clinic to give her phone number to ten women who might be willing to discuss their experience with abortion.

Over the following weeks, 91 of those 100 women told Mary that if they had had any sort of reasonable alternative, they would have chosen to give birth. Abortion, for them, had not been a matter of making a choice, but of feeling they had no other choice to make.

Mary’s response was to found in 1986 the Nurturing Network, a nationwide resource providing women in crisis pregnancies practical support. Today, after serving more than 4,500 clients, Mary knows of only one who, faced with the helps the Network offers, chose abortion.

Pregnant women who contact the Nurturing Network through its 800 number (1-800-TNN-4MOM) are asked to do just one thing: fill out an extensive questionnaire about themselves, their dreams and goals, and the obstacles their pregnancy presents.

Some need a leave of absence from their current job and a similar short-term position in another company. Others need free medical care, or a transfer to a different university. Some need a safe place to live, or adoption counseling, or parenting training.

The Network, which now includes over 18,000 contacts, prides itself on creatively meeting those needs. Each client receives counseling. Seven hundred Nurturing Homes are on call. An informal coalition of doctors provides services for free or reduced rates. A network of employers and colleges accept short-term, pregnant employees and students.

Last summer, a CBS48 Hours crew filmed the Nurturing Network in action and talked with one young client. Tall, with curly brown hair spiraling over her shoulders, she held a relaxed, smiling baby in her arms. She confessed, “I wouldn’t have had an abortion; I would have just killed myself. Without the Network, I wouldn’t even be here. I would have been just another statistic.” Woven into the philosophy of the Nurturing Network is the truth Mary learned herself years ago: suffering and loss provide an avenue for grace.

In her calm, kind way, Mary counsels clients, “The pattern you choose in response to this pregnancy will be played out again and again in your life. Rather than flee the pain, embrace it, and you will see grace poured out. In sacrificing short-term ease for a long-term benefit for someone else, you have an opportunity for lasting personal growth.”

In her multiple roles as counselor, mother, home schooler, volunteer, and executive, Mary has an unlikely time each day to replenish the well of her energies. At precisely five minutes to three—every morning—she awakens. The house is quiet. She reads her Bible, prays, writes in her journal.

During one of these middle-of-the-night interludes some years ago, a phrase recurred in Mary’s mind: “The violence that is committed against women by society today.…” Reflecting on those words fuels her efforts to help women who have been led to believe that abortion is the only solution to their crisis pregnancies. “Abortion is really the ultimate form of violence, disguised in a slogan called freedom,” says Mary. “The Nurturing Network is just one little voice that is calling out to say it doesn’t have to be that way.”

Paul Brand is a world-renowned hand surgeon and leprosy specialist. Now in semiretirement, he serves as clinical professor emeritus, Department of Orthopedics, at the University of Washington and consults for the World Health Organization. His years of pioneering work among leprosy patients earned him many awards and honors.