Most CT readers, I imagine, know the name of Oswald Chambers, author of My Utmost for His Highest, a daily devotional that has sold by the hundred thousand since first it appeared in 1927. Some will know that more than 30 other books bear Chambers’s name, most of them still in print, and all on the same theme, the supernaturalizing of natural life through a living relationship to Jesus Christ as Savior, Master, and Model. Many have acquired a taste for the distinctive flavor of Chambers’s material—cool and sharp, clinical and exuberant, pithy and searching, childlike, ardent, and profound: salt, mustard, pepper, and vinegar for the too-bland Christian life.

“The O.C.,” as the troops in Egypt called him, was a bright Scottish Baptist of wide literary, artistic, and philosophical culture. His evangelical theology was unremarkable save that he embraced the Wesleyan doctrine of entire sanctification and saw it as verified in his own experience of “baptism in the Spirit” in 1901. From 1906 he worked without stated salary for the Pentecostal League of Prayer; this was the holiness organization under whose auspices he and his wife ran the Bible Training College from 1911 to 1915, when he left for Egypt as a YMCA chaplain.

Though appreciated by those who knew his ministry, he was never in the mainstream. In his twenties he had written: “I feel I shall be buried for a time, hidden away in obscurity; then suddenly I shall flame out, do my work, and be gone.” And so it was.

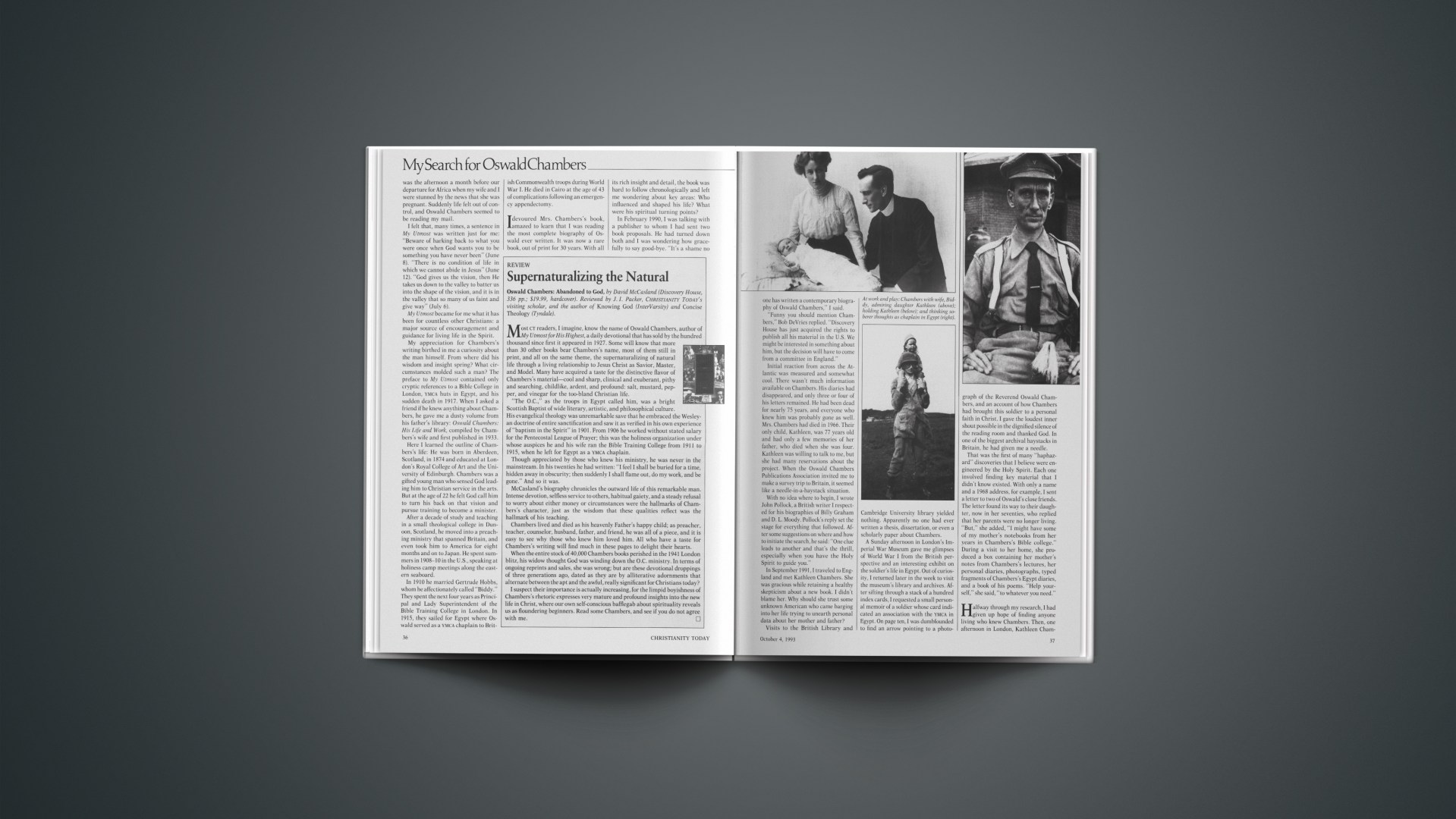

McCasland’s biography chronicles the outward life of this remarkable man. Intense devotion, selfless service to others, habitual gaiety, and a steady refusal to worry about either money or circumstances were the hallmarks of Chambers’s character, just as the wisdom that these qualities reflect was the hallmark of his teaching.

Chambers lived and died as his heavenly Father’s happy child; as preacher, teacher, counselor, husband, father, and friend, he was all of a piece, and it is easy to see why those who knew him loved him. All who have a taste for Chambers’s writing will find much in these pages to delight their hearts.

When the entire stock of 40,000 Chambers books perished in the 1941 London blitz, his widow thought God was winding down the O.C. ministry. In terms of ongoing reprints and sales, she was wrong; but are these devotional droppings of three generations ago, dated as they are by alliterative adornments that alternate between the apt and the awful, really significant for Christians today?

I suspect their importance is actually increasing, for the limpid boyishness of Chambers’s rhetoric expresses very mature and profound insights into the new life in Christ, where our own self-conscious bafflegab about spirituality reveals us as floundering beginners. Read some Chambers, and see if you do not agree with me.

J. I. Packer is CHRISTIANITY TODAY’s visiting scholar, and the author of Knowing God (InterVarsity) and Concise Theology (Tyndale).