Can forgiveness overcome the horror?

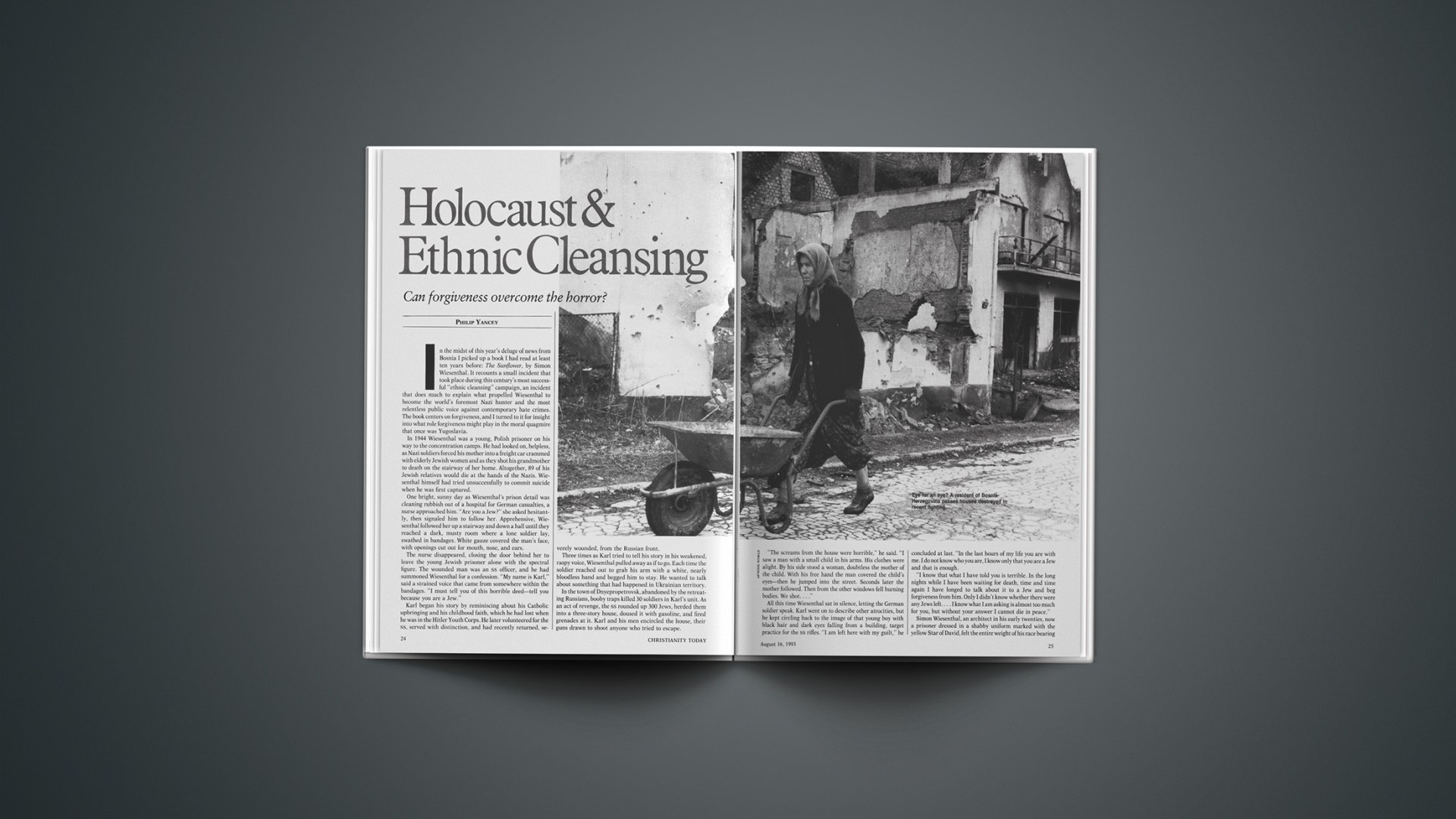

In the midst of this year’s deluge of news from Bosnia I picked up a book I had read at least ten years before: The Sunflower, by Simon Wiesenthal. It recounts a small incident that took place during this century’s most successful “ethnic cleansing” campaign, an incident that does much to explain what propelled Wiesenthal to become the world’s foremost Nazi hunter and the most relentless public voice against contemporary hate crimes. The book centers on forgiveness, and I turned to it for insight into what role forgiveness might play in the moral quagmire that once was Yugoslavia.

In 1944 Wiesenthal was a young, Polish prisoner on his way to the concentration camps. He had looked on, helpless, as Nazi soldiers forced his mother into a freight car crammed with elderly Jewish women and as they shot his grandmother to death on the stairway of her home. Altogether, 89 of his Jewish relatives would die at the hands of the Nazis. Wiesenthal himself had tried unsuccessfully to commit suicide when he was first captured.

One bright, sunny day as Wiesenthal’s prison detail was cleaning rubbish out of a hospital for German casualties, a nurse approached him. “Are you a Jew?” she asked hesitantly, then signaled him to follow her. Apprehensive, Wiesenthal followed her up a stairway and down a hall until they reached a dark, musty room where a lone soldier lay, swathed in bandages. White gauze covered the man’s face, with openings cut out for mouth, nose, and ears.

The nurse disappeared, closing the door behind her to leave the young Jewish prisoner alone with the spectral figure. The wounded man was an SS officer, and he had summoned Wiesenthal for a confession. “My name is Karl,” said a strained voice that came from somewhere within the bandages. “I must tell you of this horrible deed—tell you because you are a Jew.”

Karl began his story by reminiscing about his Catholic upbringing and his childhood faith, which he had lost when he was in the Hitler Youth Corps. He later volunteered for the SS, served with distinction, and had recently returned, severely wounded, from the Russian front.

Three times as Karl tried to tell his story in his weakened, raspy voice, Wiesenthal pulled away as if to go. Each time the soldier reached out to grab his arm with a white, nearly bloodless hand and begged him to stay. He wanted to talk about something that had happened in Ukrainian territory.

In the town of Dnyepropetrovsk, abandoned by the retreating Russians, booby traps killed 30 soldiers in Karl’s unit. As an act of revenge, the SS rounded up 300 Jews, herded them into a three-story house, doused it with gasoline, and fired grenades at it. Karl and his men encircled the house, their guns drawn to shoot anyone who tried to escape.

“The screams from the house were horrible,” he said. “I saw a man with a small child in his arms. His clothes were alight. By his side stood a woman, doubtless the mother of the child. With his free hand the man covered the child’s eyes—then he jumped into the street. Seconds later the mother followed. Then from the other windows fell burning bodies. We shot.…”

All this time Wiesenthal sat in silence, letting the German soldier speak. Karl went on to describe other atrocities, but he kept circling back to the image of that young boy with black hair and dark eyes falling from a building, target practice for the SS rifles. “I am left here with my guilt,” he concluded at last. “In the last hours of my life you are with me. I do not know who you are, I know only that you are a Jew and that is enough.

“I know that what I have told you is terrible. In the long nights while I have been waiting for death, time and time again I have longed to talk about it to a Jew and beg forgiveness from him. Only I didn’t know whether there were any Jews left.… I know what I am asking is almost too much for you, but without your answer I cannot die in peace.”

Simon Wiesenthal, an architect in his early twenties, now a prisoner dressed in a shabby uniform marked with the yellow Star of David, felt the entire weight of his race bearing down on him. He stared out the window at the sunlit courtyard. He looked at the eyeless heap of bandages lying in the bed. “At last I made up my mind,” he writes, “and without a word I left the room.”

I reread The Sunflower because the dilemma Wiesenthal faced has similarities to moral dilemmas being faced in Bosnia right now. The first half of the book tells the story I have just summarized. The next half records reactions to that story from such luminaries as Abraham Heschel, Martin Marty, Cynthia Ozick, Jacques Maritain, and Herbert Marcuse. The SS officer named Karl died, unforgiven by a Jew, but Wiesenthal lived on to be liberated from a death camp by American troops. Ever after, the scene in the hospital room haunted him. He asked fellow prisoners what he should have done. He inquired of rabbis and priests. Finally, when he wrote up the story more than 20 years after the war had ended, he sent it to the brightest ethical minds he knew—Jew, Gentile, Catholic, Protestant, and irreligious. “What would you have done in my place?” he asked. “Did I do right?”

Of the 32 men and women who responded, only 6 said Wiesenthal had done wrong in not forgiving the German. Most thought he had done right. What moral or legal authority did Wiesenthal have to forgive injuries done to someone else? they asked. One respondent quoted the poet Dryden, “Forgiveness, to the injured doth belong.”

A few of the Jewish respondents said that the enormity of Nazi crimes had exceeded all possibility of forgiveness. Herbert Gold, an American author and professor, declared, “The guilt for this horror lies so heavily on the Germans of that time that no personal reaction to it is unjustifiable.” Novelist Cynthia Ozick was more blunt: “Let the SS man die unshriven. Let him go to hell.”

Some questioned the whole concept of forgiveness. One professor dismissed forgiveness as an act of sensual pleasure, the sort of thing lovers do after a spat, before climbing back into bed. It has no place, she said, in a world of genocide and Holocaust. Forgive, and the whole business might repeat itself.

When I first read The Sunflower ten years ago, I was taken aback by the near unanimity of the responses. I expected more of the theologians and philosophers to speak of mercy. But this time as I reread the eloquent replies to Wiesenthal’s question I was struck by the terrible, crystalline logic of unforgiveness. In a world of unspeakable atrocity, forgiveness seems unjust, unfair, irrational. As the philosopher Herbert Marcuse put it, “One cannot, and should not, go around happily killing and torturing and then, when the moment has come, simply ask, and receive, forgiveness.”

Hovering above the debate, especially for the Christians, was the sharp conflict between justice and forgiveness, the great contradiction that Jesus Christ introduced into history. Some solved the contradiction the way the church traditionally has, by assigning justice to Caesar and forgiveness to church. When Martin Luther considered Jesus’ commands to turn the other cheek and love your enemies, he concluded that they applied to individuals, not to states.

Was Luther right? Is history obliged to run on two parallel tracks that never meet? Is it too much to expect that the high ethical ideals of the gospel—of which forgiveness lies at the core—might transfer into the brutal world of politics and international diplomacy? These questions nagged at me as I listened to the unremitting bad news from the former Yugoslavia.

Like most Americans, I find everything about the Balkan region confusing, unpronounceable, and perverse. After rereading The Sunflower, though, I began to see the Balkans as merely the latest stage setting for a recurring theme of history. What happened to Yugoslavia illustrates the one thing that unfair, irrational forgiveness has going for it: It is the alternative. Where unforgiveness reigns, as essayist Lance Morrow has pointed out, a Newtonian law comes into play: For every atrocity there must be an equal and opposite atrocity.

The Serbs, of course, are everybody’s whipping boy. Note the language used to describe them in Time magazine (in the supposedly objective news section): “What has happened in Bosnia is just squalor and barbarism—the filthy work of liars and cynics manipulating tribal prejudices, using atrocity propaganda and old blood feuds to accomplish the unclean political result of ‘ethnic cleansing.’ ” Caught up in righteous—and wholly appropriate—revulsion over Serbian atrocities, the world overlooks one fact: the Serbs are simply following the terrible logic of unforgiveness.

The very same political machine that eliminated 89 members of Wiesenthal’s family and provoked such harsh words from refined people like Cynthia Ozick and Herbert Marcuse directed an “ethnic cleansing” campaign against the Serbs during World War II. The Serbs killed tens of thousands; the Croats killed hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Gypsies, and Jews during the Nazi occupation of Balkan territory.

“Never again,” the rallying cry of Holocaust survivors, is also what has inspired the Serbs to defy the United Nations and virtually the entire world. Never again will they let Croats rule over territory populated by Serbs. And never again will they let Muslims, either: the last war they fought with Muslims led to 500 years of Turkish rule (in historical perspective, a period more than twice as long as the United States has even existed).

In the logic of unforgiveness, not to strike against the enemy would betray ancestors and the sacrifices they made. There is one major flaw in the inexorable law of revenge, however: it never settles the score. The Turks got revenge in 1389, at the Battle of Kesovo; the Croats got it in the 1940s; now it’s our turn, say the Serbs. Yet one day, as the Serbs surely know, the descendants of today’s raped and mutilated victims will arise to seek vengeance on the avengers. And so it goes. If everyone were to follow the “eye for an eye” principle of justice, said Gandhi, the whole world would go blind.

Forgiveness may be unfair—it is, by definition—but at least it provides a way to put a halt to the juggernaut of “justice.” Theologian Romano Guardini offers this commentary on Jesus’ tough words in the Sermon on the Mount: “As long as you cling to ‘justice’ you will never be guiltless of injustice. As long as you are tangled in wrong and revenge, blow and counterblow, aggression and defense, you will be constantly drawn into fresh wrong.… He who takes it upon himself to avenge trampled justice never restores justice.… In reality, insistence on justice is servitude. Only forgiveness frees us from the injustice of others.”

We have many vivid proofs of the end result of the law of unforgiveness. In Shakespeare’s and Sophocles’ historical tragedies, bodies litter the stage. Macbeth, Richard III, and Elektra must kill and kill and kill until they have got their revenge, then live in fear lest some enemies have survived to seek counterrevenge. Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather trilogy and Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven illustrate the same law. We see the law at work in IRA terrorists who blow up shoppers and bankers in London’s shopping and financial districts in part because of some atrocity committed in Oliver Cromwell’s day. We see it in Sri Lanka, and in India, and in the feuding republics of the former Soviet Union.

Just acknowledge your crimes against us, say the Armenians to the Turks, and we’ll stop blowing up airplanes and assassinating your diplomats. Turkey adamantly refuses. At one point during the Iran hostage crisis, the Iranian government said they would release all hostages unharmed if the U.S. President would apologize for past support of the Shah’s oppressive regime. Jimmy Carter, a born-again Christian who understands forgiveness, declined. Our national honor was at stake, he said.

Is there any place for forgiveness in the arena of nations? In a world that lives by the law of unforgiveness, where can we find creative alternatives? I can think of only a few examples.

As a nation, Germany has repented of the very abominations that prompted Simon Wiesenthal’s confrontation. Before unification, West Germany paid out $30 billion in compensation to Jews. East Germany denied any moral responsibility for 45 years, but after the cords of communism began to loosen and East Germany elected a free parliament, that body made its first order of business an act of contrition. “We feel sorrow and shame, and acknowledge this burden of German history,” said the deputies, using language rarely heard in international affairs. “We ask all the Jews of the world to forgive us.” The fact that a relationship exists at all between Germany and Israel is a stunning demonstration of transnational forgiveness.

In 1983, before the Iron Curtain fell, Pope John Paul II came to Poland during a period of martial law and conducted an open-air mass. Hour after hour, throngs of people streamed across the Poniatowski Bridge to the designated stadium. Organized by parishes, they marched in orderly rows on a route that passed in front of the Communist party’s Central Committee Building. All afternoon the marchers chanted in unison, “We forgive you! We forgive you!”

Today, all over Eastern Europe, dramas of forgiveness large and small are being played out. Should a pastor in Russia forgive the KGB officers who imprisoned him and razed his church? Should citizens of East Germany forgive the Stasi stool pigeons—including seminary professors, pastors, and treacherous spouses—who spied on them? Forgiveness is never easy, and it may take generations, but is there any other way to break the chain and undo the effects of history?

We in the United States have had some experience with forgiveness on a national scale. Archenemies in World War II, Germany and Japan are now two of our staunchest allies. Even more significant—and of more relevance to former Yugoslavia—we fought a bloody Civil War that set family against family and the nation against itself. I grew up in Atlanta, where attitudes toward William Tecumseh Sherman suggest how Bosnian Muslims must view their Serbian neighbors. It was Sherman, after all, who first introduced the “scorched earth” tactics of modern warfare, a policy recently refined to perfection in the Balkans.

Yet somehow our nation did survive, as one. Southerners still debate the merits of the Confederate flag and the song “Dixie,” but I haven’t heard much talk of secession lately, or of dividing the nation into ethnic enclaves. Our President hails from Arkansas, our Vice-president from Tennessee.

Even more impressive are the steps toward reconciliation between white and black races, one of which used to own the other. Racism, with all its lingering effects, shows that forgiveness in itself does not undo injustice. Still, there are signs of hope. In 1982 Americans saw the extraordinary scene of George Wallace appearing before the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to apologize for his past behavior to blacks. His appearance—he needed their votes in a tight race for governor—was easier to understand than their response. Black leaders accepted his apology, and black citizens forgave him, voting for him in droves.

In one sense, every step blacks have taken to join the U.S. as active citizens can be viewed as an implicit act of forgiveness. Not all blacks forgive, not all whites repent. Racism deeply divides this country. Yet compare our situation with what has happened in, say, Yugoslavia. I have not seen any machinegunners blocking the routes to Atlanta, or artillery shells raining down in Birmingham.

We dare not simplify the realities of international politics. I do not know how I would have responded in Simon Wiesenthal’s position. I do not know how forgiveness applies in a place like the former Yugoslavia. I have difficulty even imagining forgiveness on a national or global scale. When Iran demanded an apology of the U.S., were they seeking to forgive us, or were they merely posturing, looking for a way to score diplomatic points? I suspect the latter.

When I contemplate forgiveness, I find it easier to consider individual, personal acts. Politics deals with externals—borders, wealth, crimes—and has no cure for evil. Authentic forgiveness, lasting forgiveness, deals with the evil in a person’s heart. Virulent evil (racism, ethnic hatred) spreads through society like an airborne disease; one cough infects a whole busload. But the cure, like a vaccine, must be applied one person at a time.

I think of Martin Luther King, Jr., who recorded his struggle with forgiveness in “Letter from Birmingham City Jail.” Outside the jail, Southern pastors were denouncing him as a Communist, mobs were yelling “Hang the nigger!” and policemen were swinging nightsticks at his unarmed supporters. King writes that he decided to fast for several days, an act of spiritual discipline necessary for him to forgive his enemies.

I think, too, of Corrie Ten Boom, who preached on forgiveness one day in Munich and afterward found herself confronting face to face an SS guard from her wartime concentration camp. “Lord, forgive me, I cannot forgive,” she prayed, and the hatred inside her melted away.

Ten years ago a drama of personal forgiveness captured the world’s fleeting attention. Pope John Paul II went into the bowels of Rome’s Rebibbia prison to visit Mehmet Ali Agca, a hired assassin who had tried to kill him and nearly succeeded. “I forgive you,” said the Pope, as video cameras whirred.

Time magazine, its editors impressed by the event, devoted a cover story to it. Lance Morrow wrote, “John Paul meant, among other things, to demonstrate how the private and public dimensions of human activity may fuse in moral action.… Seeing the largest possible meanings in the most intimate places of the soul, John Paul wanted to proclaim that great issues are determined, or at least informed, by the elemental impulses of the human breast—hatred or love.” Morrow went on to quote a Milanese newspaper that, remarking on the Pope’s “courage,” said, “There will be no escape from wars, from hunger, from misery, from racial discrimination, from denial of human rights, and not even from missiles, if our hearts are not changed.”

Morrow added, “The scene in Rebibbia had a symbolic splendor. It shone in lovely contrast to what the world has witnessed lately in the news. For some time, a suspicion has taken hold that the trajectory of history is descendant, that the world moves from disorder to greater disorder, toward darkness—or else toward the terminal global flash. The symbolism of the pictures from Rebibbia is precisely the Christian message, that people can be redeemed, that they are ascendant toward the light.”

For Lance Morrow, at least, a singular act of forgiveness had consequences extending far beyond the walls of a prison cell. It introduced the possibility of a different kind of transforming power. John Paul’s deed shone all the more brightly because of its dim setting: a bare cell, a perfect backdrop for the dreary law of unforgiveness.

The Pope, of course, was following the example of one who did not survive an attempt against his life. The kangaroo courts of Judea found a way to inflict a sentence of capital punishment on the only perfect man who ever lived. From the cross, Jesus pronounced his own countersentence, striking an eternal blow against the law of unforgiveness: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

The Roman soldiers, Pilate, Herod, even the Jewish Sanhedrin, were “just doing their jobs”—the monotonous excuse later used to explain Auschwitz, My Lai, and the Gulag—but Jesus stripped away that institutional veneer and spoke to the human heart. It was forgiveness they needed, more than anything else. We know, those of us who believe in the Atonement, that Jesus had in mind far more than Roman soldiers and the Sanhedrin when he spoke those words. He had us in mind. In the Cross, and only in the Cross, he put an end to the law of eternal consequences.

The leap from personal forgiveness to corporate forgiveness crosses a very deep chasm. We need only look at Christian history after the Cross. Jesus offered forgiveness; his followers have persecuted his own race as “Christ-killers” ever since.

In a world where force matters most, forgiveness may seem ethereal, insubstantial. Stalin once scoffed at the moral authority of the church: “How many divisions has the Pope?” And yet history shows that forgiveness can indeed be a powerful weapon in the making of peace. Acts by individuals like the Pope and Martin Luther King, Jr., strike a blow against the law of unforgiveness, symbolically pointing to another way. Great leaders—Lincoln, Gandhi, and Anwar Sadat come to mind, all of whom paid the ultimate price for defying the law of unforgiveness—can help create a national climate that leads to reconciliation. How different would current events be if Sadat and not Saddam ruled Iraq? Or if a Lincoln emerged in Yugoslavia?

Can forgiveness play a role in the former Yugoslavia even now? It must, or the people there will have no hope of living together. As so many abused children learn, without forgiving those who hurt us, we cannot free ourselves from the grip of history. What is true of individuals is true also of nations.

I have a friend whose marriage has gone through rough times. One night George passed a breaking point and emotionally exploded. He pounded the table and floor. “I hate you!” he screamed at his wife. “I won’t take it anymore! I’ve had enough! I won’t go on! I won’t let it happen! No! No! No!”

Several months later my friend woke up in the middle of the night and heard strange sounds coming from the room where his two-year-old son slept. He went down the hall, stood outside his son’s door, and shivers ran through his flesh. In a soft voice, the two-year-old was repeating word for word with precise inflection the climactic argument between his mother and father. “I hate you.… I won’t take it anymore.… No! No! No!”

George realized that in some awful way he had just passed on his pain and anger and unforgiveness to the next generation. Is not that what is happening all over Yugoslavia now?

Apart from forgiveness, the monstrous past may awake at any time from hibernation and devour the present—and even the future.

Loren Wilkinson is the writer/editor of Earthkeeping in the ’90s (Eerdmans) and the coauthor, with his wife, Mary Ruth Wilkinson, of Caring for Creation in Your Own Backyard (Servant). He teaches at Regent College in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.