Say the word prolife and the mind’s eye sees picketers jamming sidewalks outside the Supreme Court, “rescuers” hauled off by police using chokeholds, protesters chanting that abortion is murder. Prolife is an army fighting in the streets, struggling for the allegiance of voters, congressmen, governors, and judges.

But a different, quieter, nonpolitical war goes on in the hearts and minds of women contemplating abortion. Their decisions are private. They are often terrified and embarrassed as, amid the rhetoric and emotion of political war, they make one of the most crucial decisions of their lives. Fighting for their allegiance is a different kind of prolife force, an invisible, unpublicized army of women. Few of its volunteers would be willing to picket or protest. Their style is care, not confrontation. They cooperate in highly local, grassroots efforts, working out of small, storefront offices in perhaps 1,500 locations nationally, seeing an estimated 700,000 to 1,000,000 women annually.

The Crisis Pregnancy Center (CPC) of Richmond, California, for example, fills a converted dentist’s office in back of a pharmacy on a gritty, commercial street. The women who enter—about 120 each month—are mostly poor, often Hispanic. Richmond is a tough, working-class city. Women come to the center because they have seen its ad in the Yellow Pages offering a free pregnancy test, or because a friend has told them they can find free maternity clothes.

In small, tidy rooms once filled with dentists’ chairs, women sit with other women and talk one on one about what to do with the “problem” inside their bodies, and the problems outside, too. The center’s counselors are not professionals, though they go through a 32-hour training course and 20 hours of in-service preparation. As Christians, they volunteer because they feel concerned about abortion, and they believe that supporting pregnant women is the most practical way to limit it.

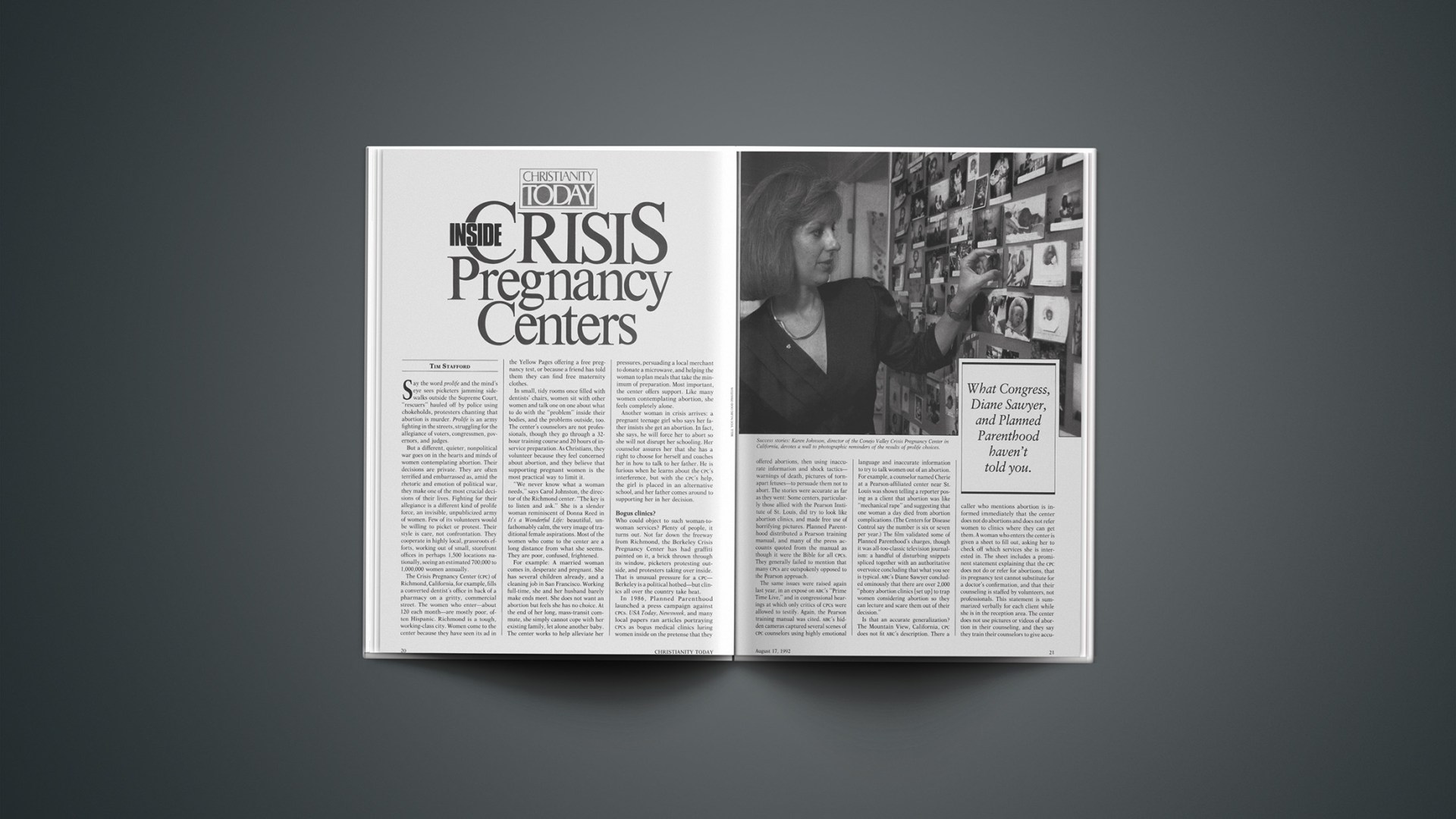

“We never know what a woman needs,” says Carol Johnston, the director of the Richmond center. “The key is to listen and ask.” She is a slender woman reminiscent of Donna Reed in It’s a Wonderful Life: beautiful, unfathomably calm, the very image of traditional female aspirations. Most of the women who come to the center are a long distance from what she seems. They are poor, confused, frightened.

For example: A married woman comes in, desperate and pregnant. She has several children already, and a cleaning job in San Francisco. Working full-time, she and her husband barely make ends meet. She does not want an abortion but feels she has no choice. At the end of her long, mass-transit commute, she simply cannot cope with her existing family, let alone another baby. The center works to help alleviate her pressures, persuading a local merchant to donate a microwave, and helping the woman to plan meals that take the minimum of preparation. Most important, the center offers support. Like many women contemplating abortion, she feels completely alone.

Another woman in crisis arrives: a pregnant teenage girl who says her father insists she get an abortion. In fact, she says, he will force her to abort so she will not disrupt her schooling. Her counselor assures her that she has a right to choose for herself and coaches her in how to talk to her father. He is furious when he learns about the CPC’s interference, but with the CPC’s help, the girl is placed in an alternative school, and her father comes around to supporting her in her decision.

Bogus Clinics?

Who could object to such woman-to-woman services? Plenty of people, it turns out. Not far down the freeway from Richmond, the Berkeley Crisis Pregnancy Center has had graffiti painted on it, a brick thrown through its window, picketers protesting outside, and protesters taking over inside. That is unusual pressure for a CPC—Berkeley is a political hotbed—but clinics all over the country take heat.

In 1986, Planned Parenthood launched a press campaign against CPCs. USA Today, Newsweek, and many local papers ran articles portraying CPCs as bogus medical clinics luring women inside on the pretense that they offered abortions, then using inaccurate information and shock tactics—warnings of death, pictures of torn-apart fetuses—to persuade them not to abort. The stories were accurate as far as they went: Some centers, particularly those allied with the Pearson Institute of St. Louis, did try to look like abortion clinics, and made free use of horrifying pictures. Planned Parenthood distributed a Pearson training manual, and many of the press accounts quoted from the manual as though it were the Bible for all CPCs. They generally failed to mention that many CPCs are outspokenly opposed to the Pearson approach.

The same issues were raised again last year, in an exposé on ABC’s “Prime Time Live,” and in congressional hearings at which only critics of CPCs were allowed to testify. Again, the Pearson training manual was cited. ABC’s hidden cameras captured several scenes of CPC counselors using highly emotional language and inaccurate information to try to talk women out of an abortion. For example, a counselor named Cherie at a Pearson-affiliated center near St. Louis was shown telling a reporter posing as a client that abortion was like “mechanical rape” and suggesting that one woman a day died from abortion complications. (The Centers for Disease Control say the number is six or seven per year.) The film validated some of Planned Parenthood’s charges, though it was all-too-classic television journalism: a handful of disturbing snippets spliced together with an authoritative overvoice concluding that what you see is typical. ABC’s Diane Sawyer concluded ominously that there are over 2,000 “phony abortion clinics [set up] to trap women considering abortion so they can lecture and scare them out of their decision.”

Is that an accurate generalization? The Mountain View, California, CPC does not fit ABC’s description. There a caller who mentions abortion is informed immediately that the center does not do abortions and does not refer women to clinics where they can get them. A woman who enters the center is given a sheet to fill out, asking her to check off which services she is interested in. The sheet includes a prominent statement explaining that the CPC does not do or refer for abortions, that its pregnancy test cannot substitute for a doctor’s confirmation, and that their counseling is staffed by volunteers, not professionals. This statement is summarized verbally for each client while she is in the reception area. The center does not use pictures or videos of abortion in their counseling, and they say they train their counselors to give accurate, unemotional information.

Connie David, director of the Mountain View center, is a thoroughly modern woman whose first marriage ended after she refused to have an abortion. After years as a single mother, she and three children were living with the man who is now her husband when a pastor’s confrontation led them to accept Jesus Christ. Her concern for children is broader than the abortion cause; before becoming a CPC director she worked with autistic children. Now her office bulletin board is covered with photos of mothers and their children whom she has come to know through the center.

The Mountain View center will not allow volunteers to work with Operation Rescue. “It’s a different mindset,” says David. “It doesn’t work in the counseling room. We believe that as we meet the needs of women, we meet the needs of the unborn child.”

Another CPC, in Wichita, Kansas, takes a different tack. Director Linda Hale spent a month in prison during last summer’s abortion protests; today she is mothering the child of a woman she met inside. She says she feels more radical than other CPC directors. “We have a third-trimester abortionist in Wichita,” she explains. “You can [stand outside and] see women who are obviously in their third trimester go in on a Monday, and come out Friday obviously not pregnant. It makes you more radical.” If callers ask point blank whether her center does abortions she will say they don’t, but her strategy is to dodge the question if she can. “We’d like for them first to get in here, and find out what we’re all about.” She admits that some women become angry when they realize what kind of center they have entered.

Which center is more typical? No one can say for certain. No one even knows how many CPCs exist: estimates range from 1,500 to 3,000. What is known is that the two largest umbrella organizations, Christian Action Council (CAC) and Birthright, have a policy of insisting on truthfulness and respect for women. They discourage involvement in political protests. These comprise nearly 1,000 centers and would seem to represent the mainstream. (Hale’s Wichita center is affiliated with the Christian Action Council, but Harriet Lewis, CAC vice-president, says Hale is the only CAC director involved in protests and that her case would be extremely rare, even among counselors.)

More typical is Robin McDonald, director of the Capitol Hill CPC in Washington, D.C.: “Our philosophy is to minister to women in a way that never, ever undermines their dignity.” Shari Plunkett, who oversees the Richmond and Berkeley centers, along with an innovative prenatal medical clinic in Oakland, California, agrees: “We train our counselors that they’re not here to tell any woman what to do. We’re here to help women, to give accurate information, and any resources we have.”

The Pearson Institute, on the other hand, is on record that with babies’ lives at stake, aggressive tactics are justified. Pearson claimed 200 clinics at one time, but knowledge of the organization is shadowy, and CHRISTIANITY TODAY was unable to contact its leaders. (One needs a special security code to reach their headquarters by telephone.) According to Conrad Wojnar of Des Plaines Pro-Life, the Pearson organization, always loose, is nearly defunct. Wojnar has been trying to rebuild a network of centers with the Pearson philosophy and estimates that about 100 remain. “We don’t lie,” he says. “We tell [women] when they ask about abortion that we need to talk to you and would you like to make an appointment. Most of the women are so brainwashed about abortion that they only see us as fanatics. It’s what we call abortion tunnel vision.”

Outside of the umbrella organizations are many independent centers—such as those in Richmond and Berkeley—but nobody knows how many or what methods and morals predominate.

At The Grassroots

Crisis-pregnancy centers vary in other ways as well. Take the two in Santa Rosa, California. The Pregnancy Counseling Center, a CAC affiliate, takes pride in its trim, professional office space, where they see women by appointment. Birthright, four blocks away on a downtown street, takes no appointments but welcomes drop-ins to a second-floor office full of sagging furniture, homey wall plaques, and a portable electric heater to take the chill off a cold day. Birthright is led by two kindly older women who receive no salary. The Pregnancy Counseling Center has three professional staff members. The contrast in styles reflects national distinctives: The Christian Action Council emphasizes professionalism, while Birthright’s founder, Louise Summerhill, stressed the value of informality. Birthright, in Santa Rosa as elsewhere, began with close, informal links to the Catholic church. Pregnancy Counseling Center volunteers are mostly conservative Protestants.

Despite the differences in style, the two centers offer a similar menu of services. As with CPCs all over the country, a free, self-administered pregnancy test (advertised in the Yellow Pages) brings in a large share of new clients. (They often make their first contact through a crisis hot line.) A volunteer assists women as they take the test and offers information about abortion procedures and the alternatives to abortion. The counselors try to help the women think through all the implications—emotional and practical—of their decision. For women whose tests are negative (nearly 50 percent are), counselors try to talk about the relationships with men that have made pregnancy a crisis, rather than a joy.

Increasingly, centers offer postabortion counseling, often in the form of a small-group Bible study that examines the stages of grief. CPC leaders point to this as proof that they are not harsh and judgmental; if they were, how many women would come to them for help after an abortion?

Nevertheless, there is no doubt where CPCs stand: None of them offers referrals to abortion clinics. Nor, for that matter, do they offer contraceptive information, preferring to stress abstinence for those not married.

Beyond the decision, most centers help women carry their babies to term. CPCs almost always have a room filled with neatly arranged second-hand baby and maternity clothes. Other practical helps may include a place to stay with a family, parenting classes, nutrition classes, prenatal medical care, even job training. Bethany Christian Services, which operates 55 centers, is particularly known for helping arrange adoptions.

About 75 percent of pregnant women who come to CAC-affiliated centers choose to carry their babies to term. Nearly all raise their babies themselves. The centers do not deliberately discourage adoption, but as Susan and Marvin Olasky point out in their pro-adoption book More than Kindness (Crossway), they may inadvertently do so by assuring young women that they will be supported through and after their pregnancy—in a sense, treating too lightly the difficulties of single parenting.

Women In Crisis

Thousands of grassroots organizations offer a variety of support and care to women with crisis pregnancies. A sampling:

Bethany Christian Services was founded in 1944 by two Grand Rapids, Michigan, women concerned for the needs of pregnant girls. Bethany operates a national hotline that refers pregnant women to local help. It also staffs 55 centers with professional counselors. It is especially oriented toward women who have already decided to carry their child to term. Bethany is the largest private adoption agency in America and has stayed close to its evangelical beginnings.

Birthright International is the brainchild of the late Louise Summerhill, a Catholic housewife who launched a movement while raising seven children. Begun in Toronto in 1968, Birthright relies almost entirely on volunteers to run 475 crisis-pregnancy centers in the U.S. and 75 in Canada. Birthright centers often have informal links to the Catholic church.

Christian Action Council began as a political lobby when evangelical Protestants joined Catholics in their post-Roe v. Wade opposition to abortion. Six years later, in 1981, the CAC began organizing crisis-pregnancy centers. Today 425 centers are affiliated. They follow Birthright’s pattern in most ways but emphasize evangelism and a more professional image.

The Nurturing Network targets college students and working women who are concerned that having a baby will halt their education or career. Begun by Mary Cunningham Agee, a former Bendix executive, the network enlists thousands of professional women to offer support and counseling, as well as confidential job and college transfers.

Truly Prochoice?

Both critics and leaders of crisis-pregnancy centers believe that the heart of the abortion dilemma is a difficult crisis in the life of a woman. They hold very different images of women with crisis pregnancies, however. Abortion-rights advocates usually talk about women who have carefully, painfully made up their minds to have an abortion, wander inadvertently into a CPC for a free test, and receive a house-of-horrors lecture. CPC counselors say that kind of mind-made-up woman rarely comes to them (and when she does, they say, they don’t lecture her; they try to let her know that they’re available to support her after her abortion).

Far more common, they say, are young women in a panic, who think they must have an abortion because there are no alternatives. Robin McDonald’s Capitol Hill CPC serves mainly poor African-American women. “These poor, black women really don’t want to have an abortion,” she says. “Disadvantaged women want advantages; they don’t want to kill their children. Eighty-one percent of those who come to our center choose life for their babies. With support and encouragement, women will opt for life.”

“I find it so ironic that prochoice people are proabortion,” says Sue Russell, a volunteer counselor in Mountain View. “Almost every woman who comes in says, ‘I have to have an abortion. I have no choice.’ ” CPCs exist to help women see that they do have a choice. Donna Cornell, who directs a Santa Rosa, California, CPC, says that “most of the time when there’s nocounseling, women make a decision based on outside pressure. They are basing a decision on what someone else wants them to do. We try to get them to think what in their heart they really want to do. We truly are prochoice, in the truest sense of the word.”

If CPCs favor choice, critics ask, why won’t they refer women to abortion clinics? In answering that, CPC leaders point out that such information is as close as the phone book. But the heart of their answer is that one can respect women’s choices without being neutral about those choices. Connie David says, “My feeling is that no one is neutral about abortion. I used to say we give objective counseling. I now say we give accurate information. Our view is colored. Planned Parenthood’s is colored.” Many of the free pregnancy tests offered in the Yellow Pages are given by abortion providers, who have a financial as well as a philosophical bias in favor of abortion. It’s not clear that their counseling, or anyone’s in this extremely polarized debate, is unbiased.

Critics come closer to the mark when they ask why CPCs don’t advertise themselves as prolife organizations. Shouldn’t they let their bias be known? CPCs do have a problem: Their primary service—counseling—is one women aren’t looking for, particularly from a movement seen as moralistic and shrill. CPC counselors say that most women, when they sense warmth and concern, are eager to talk; it isn’t hard to engage them in dialogue. But dialogue is not what they came for. So CPCs run into the kind of hazard that attends certain forms of evangelism (and certain forms of condominium sales). They offer something women want—a pregnancy test or free maternity clothes—with the goal of presenting something women don’t know they want.

The Mountain View CPC, for example, shows exemplary care in explaining up front the limitations on their services. A client who checks off “pregnancy test” on her initial intake form, however, will usually get more than a simple test. The counselor will fill out a client-information form, noting such things as religious preference, and will ask questions such as, “How would you feel if your test would be positive today?” and “How would you feel about an abortion?” She will do everything she can to get into a conversation about the woman’s dilemma. Most women are grateful for a chance to talk. Indeed, as the CAC’s Harriet Lewis puts it, “When we advertise that we give caring support, that is something we are gladly bound to deliver. When we take the time to talk to her, we are giving her exactly what we advertise.” Some, however, are bound to feel that they have been manipulated into a discussion they never sought.

Tom Glessner, president of the Christian Action Council, notes that CAC affiliates ask every client to fill out an exit evaluation, and that these evaluations turn out overwhelmingly positive. He also points out that the CPCs’ number-one source of referrals is former clients. Most CPC counselors surely are empathetic and helpful, not judgmental. Nonetheless, the dilemma remains. CPCs offer women in crisis something they need—a chance to slow down and talk over what they are facing. But that is not what they are looking for when they thumb through the Yellow Pages.

Squeezing The Pipeline

CPC opponents have attacked this point of vulnerability by taking on CPCs’ Yellow Pages advertising. Until recently, many CPCs were listed under “Clinics,” where most abortion providers advertise. Now, many Yellow Pages insist that CPCs list their ads under “Abortion Alternatives,” and some include a statement that abortion alternatives don’t offer abortions or refer for them. Even that may not be enough: Testimony at congressional hearings last year raised the concern that women might still be confused by the proximity of “Abortion Alternatives” to “Abortion” listings. According to Mountain View’s Connie David, a recent letter from Yellow Pages officials announces that “Abortion Alternative” will be dropped throughout California, and all CPCs moved to a new “Pregnancy Counseling” listing. David says she will fight the move, which she believes is intended to make their advertising as ineffectual as possible. Nearly half her clients come through Yellow Pages advertising.

Other kinds of advertising—radio, newspapers—have proven effective, but expensive. The Mountain View center dropped a successful advertisement on buses after the county insisted the ad state that the center does not do or refer for abortions. Director David says, “Plumbers don’t have to advertise, ‘Not a carpenter.’ ” Birthright places ads for their 800 number in national publications like People, but can’t afford to do it often.

A few CPCs have begun offering prenatal medical services. Dr. Geeta Swamidass is the executive director of Living Well, which operates six CAC-affiliated clinics. She explains that a woman must see a doctor to confirm the results of a self-administered pregnancy test. Using volunteer, prolife doctors, Living Well enables women to hear their baby’s heartbeat, or see a picture of the baby through ultrasound. That brings home the reality of the life inside them. What is more, a medical doctor seems a more trustworthy source of information than do volunteer counselors. Equipping a clinic for medical care is expensive and bureaucratically complex, but it conveys a sense of legitimacy. It also enables Living Well to advertise under “clinic.”

Such moves may be unnecessary, however, if CPCs can develop an image that is distinct from the combative side of the prolife movement. Most CPCs send speakers into schools and churches to provide educational seminars, which helps build their reputation. Nowadays many CPC clients come from community referrals, sometimes from secular social-service agencies. (Mountain View has even had referrals from Planned Parenthood.) In time, CPCs may become genuinely trusted community institutions. As of today, however, they remain under suspicion.

Part Of The Family

For the invisible army of CPC volunteers, abortion is less a legal struggle than a struggle of women in crisis. Working with these women every day, workers are not prone to describe them as selfish or thoughtless. But the quick fix of abortion is an illusion, they insist. If we learn anything from these women, they say, it is that their crises cannot be fixed by an abortion. After an abortion, a woman goes back to the same pattern of life, to the same abusing men and blighted relationships she has always known. CPC counselors want to prevent abortions, but they want even more to touch women at a point of need and help them to change their lives. They believe that when women are assured of support, they rarely choose abortion.

Frederica Mathewes-Green, a leader in the antiabortion Feminists for Life, writes that “Somehow the ‘private, personal’ dilemma of unplanned pregnancy has become one that we as a society expect a woman to face alone. If she grieves or struggles, mourns an abortion, or battles to support herself and a hungry child, well, that was her choice wasn’t it? She has become invisible to us. In order to help her we must begin to see her again, and to see her as one of our family.”

At their best, CPC’s do that. Though they hardly replace the traditional supports of family, church, and community, CPCs try to break down the isolation of problem pregnancies. They try to treat the whole person, not merely her uterus, by bringing women into a network of support.

Three complaints are made against the prolife movement: that it is dominated by men, that it treats women’s tragic dilemmas judgmentally, and that it does nothing to care for babies after they are born. The work of CPCs overturns each of these charges.