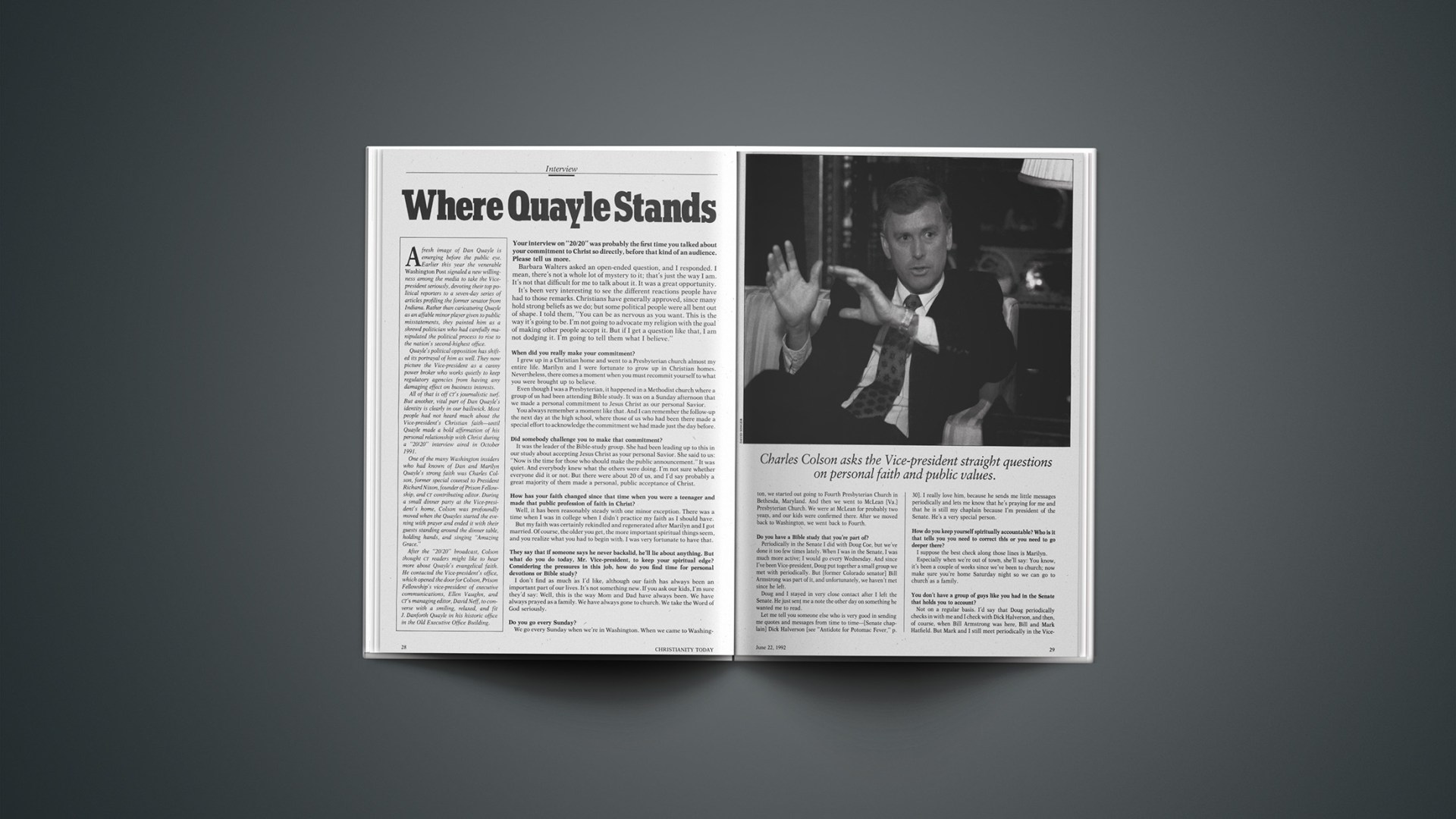

Charles Colson asks the Vice-president straight questions on personal faith and public values.

Afresh image of Dan Quayle is emerging before the public eye. Earlier this year the venerable Washington Post signaled a new willingness among the media to take the Vice-president seriously, devoting their top political reporters to a seven-day series of articles profiling the former senator from Indiana. Rather than caricaturing Quayle as an affable minor player given to public misstatements, they painted him as a shrewd politician who had carefully manipulated the political process to rise to the nation’s second-highest office.

Quayle’s political opposition has shifted its portrayal of him as well. They now picture the Vice-president as a canny power broker who works quietly to keep regulatory agencies from having any damaging effect on business interests.

All of that is off CT’s journalistic turf. But another, vital part of Dan Quayle’s identity is clearly in our bailiwick. Most people had not heard much about the Vice-president’s Christian faith—until Quayle made a bold affirmation of his personal relationship with Christ during a “20/20” interview aired in October 1991.

One of the many Washington insiders who had known of Dan and Marilyn Quayle’s strong faith was Charles Colson, former special counsel to President Richard Nixon, founder of Prison Fellowship, and CT contributing editor. During a small dinner party at the Vice-president’s home, Colson was profoundly moved when the Quayles started the evening with prayer and ended it with their guests standing around the dinner table, holding hands, and singing “Amazing Grace.”

After the “20/20” broadcast, Colson thought CT readers might like to hear more about Quayle’s evangelical faith. He contacted the Vice-president’s office, which opened the door for Colson, Prison Fellowship’s vice-president of executive communications, Ellen Vaughn, and CT’s managing editor, David Neff, to converse with a smiling, relaxed, and fit J. Danforth Quayle in his historic office in the Old Executive Office Building.

Your interview on “20/20” was probably the first time you talked about your commitment to Christ so directly, before that kind of an audience. Please tell us more.

Barbara Walters asked an open-ended question, and I responded. I mean, there’s not a whole lot of mystery to it; that’s just the way I am. It’s not that difficult for me to talk about it. It was a great opportunity.

It’s been very interesting to see the different reactions people have had to those remarks. Christians have generally approved, since many hold strong beliefs as we do; but some political people were all bent out of shape. I told them, “You can be as nervous as you want. This is the way it’s going to be. I’m not going to advocate my religion with the goal of making other people accept it. But if I get a question like that, I am not dodging it. I’m going to tell them what I believe.”

When did you really make your commitment?

I grew up in a Christian home and went to a Presbyterian church almost my entire life. Marilyn and I were fortunate to grow up in Christian homes. Nevertheless, there comes a moment when you must recommit yourself to what you were brought up to believe.

Even though I was a Presbyterian, it happened in a Methodist church where a group of us had been attending Bible study. It was on a Sunday afternoon that we made a personal commitment to Jesus Christ as our personal Savior.

You always remember a moment like that. And I can remember the follow-up the next day at the high school, where those of us who had been there made a special effort to acknowledge the commitment we had made just the day before.

Did somebody challenge you to make that commitment?

It was the leader of the Bible-study group. She had been leading up to this in our study about accepting Jesus Christ as your personal Savior. She said to us: “Now is the time for those who should make the public announcement.” It was quiet. And everybody knew what the others were doing. I’m not sure whether everyone did it or not. But there were about 20 of us, and I’d say probably a great majority of them made a personal, public acceptance of Christ.

How has your faith changed since that time when you were a teenager and made that public profession of faith in Christ?

Well, it has been reasonably steady with one minor exception. There was a time when I was in college when I didn’t practice my faith as I should have.

But my faith was certainly rekindled and regenerated after Marilyn and I got married. Of course, the older you get, the more important spiritual things seem, and you realize what you had to begin with. I was very fortunate to have that.

They say that if someone says he never backslid, he’ll lie about anything. But what do you do today, Mr. Vice-president, to keep your spiritual edge? Considering the pressures in this job, how do you find time for personal devotions or Bible study?

I don’t find as much as I’d like, although our faith has always been an important part of our lives. It’s not something new. If you ask our kids, I’m sure they’d say: Well, this is the way Mom and Dad have always been. We have always prayed as a family. We have always gone to church. We take the Word of God seriously.

Do you go every Sunday?

We go every Sunday when we’re in Washington. When we came to Washington, we started out going to Fourth Presbyterian Church in Bethesda, Maryland. And then we went to McLean [Va.] Presbyterian Church. We were at McLean for probably two years, and our kids were confirmed there. After we moved back to Washington, we went back to Fourth.

Do you have a Bible study that you’re part of?

Periodically in the Senate I did with Doug Coe, but we’ve done it too few times lately. When I was in the Senate, I was much more active; I would go every Wednesday. And since I’ve been Vice-president, Doug put together a small group we met with periodically. But [former Colorado senator] Bill Armstrong was part of it, and unfortunately, we haven’t met since he left.

Doug and I stayed in very close contact after I left the Senate. He just sent me a note the other day on something he wanted me to read.

Let me tell you someone else who is very good in sending me quotes and messages from time to time—[Senate chaplain] Dick Halverson [see “Antidote for Potomac Fever,” p. 30]. I really love him, because he sends me little messages periodically and lets me know that he’s praying for me and that he is still my chaplain because I’m president of the Senate. He’s a very special person.

How do you keep yourself spiritually accountable? Who is it that tells you you need to correct this or you need to go deeper there?

I suppose the best check along those lines is Marilyn.

Especially when we’re out of town, she’ll say: You know, it’s been a couple of weeks since we’ve been to church; now make sure you’re home Saturday night so we can go to church as a family.

You don’t have a group of guys like you had in the Senate that holds you to account?

Not on a regular basis. I’d say that Doug periodically checks in with me and I check with Dick Halverson, and then, of course, when Bill Armstrong was here, Bill and Mark Hatfield. But Mark and I still meet periodically in the Vice-president’s office just outside the Senate floor.

During the primary elections the press has been debating whether a candidate’s personal behavior and private morality have public significance. Are these areas the public’s business?

Certainly. When you’re the President or the Vice-president, you’re going to have your whole life out there for inspection. Now the question is, what is relevant and not relevant?

Well, what a person does privately is a very good indicator of what he’s going to do publicly. What a person is like personally will give you an indication of where he’s going to take the country. And if you have somebody who wants to be President or Vice-president, why would they want to hide, to keep things private? Why wouldn’t they want to be open and say, here’s what I’m all about? I’ve always believed that you should practice what you preach. And if you’re preaching something different than you’re practicing, we ought to know about it.

With the election of Presidents Reagan and Bush, evangelicals felt they had access to the administration on important issues, and they hoped to see policy changes in a number of areas, including abortion and school choice.

But there has been a high level of frustration among many evangelicals over the last eight years. Could you speak to that sense of frustration our readers might have and also talk about the future? If they vote for a Bush-Quayle ticket in the fall, what kind of policy changes can be expected in their areas of concern?

Let me try to look at the big picture first, and then break it down into some of the issues.

This election will be very value oriented. And evangelicals in particular will find this time around—as they did in 1984 and 1988—that there is a clear-cut choice on values. Values, not just abortion, but values in the family, values of what American culture should be.

I hope this will be the key chapter in a spiritual revolution that we really need. You will see underneath the campaign rhetoric a fight over whether we’re going to have a spiritual revolution and how important one’s faith is in leading this country. And you’re going to see a big difference between the values on certain social issues by this President and his wife and family, on the one hand, and the values held by the opposition, on the other.

It will be very clear-cut, and once evangelicals analyze this, they will become scared of the prospect of having a different set of values occupying the White House than occupies it today.

That’s the big picture. Now let’s get down to issues. I can identify with evangelicals’ frustration on the abortion issue. But [Senate majority leader] George Mitchell is probably not going to bring up that proabortion bill [the Freedom of Choice Act] because he knows that there are many areas in which we have political support—such as parental consent for a minor to get an abortion, or not having abortion just because someone would rather have a boy than a girl or vice versa. And they’re going to run into some of the areas where we are very powerful politically.

Whenever I get a chance, I point out that something like 1,100 abortions are performed every day in this country. Does this cavalier treatment of the most innocent bleed over into the increase in rape, child abuse, and child neglect?

I understand some voters’ frustration. But it’s a political battle. And I think we’re going to have to refocus our energies a bit and aim at the things that we can change, such as the perception out there that the prolife agenda is not politically viable. (I’m speaking as a politician now.)

You have been quoted as saying you were going to “finesse” the abortion issue.

That was Pat Buchanan’s people interpreting what I said. I never used the word finesse. We called Buchanan’s people the other day, and I think they corrected it. As a matter of fact, I’ve said all along we were not going to change the platform. The President has no interest in changing the platform. I have said we’re going to have to work out the differences in our party, but we’re not changing the prolife position of our party’s platform.

We want to include rather than exclude. As a political conservative, I look at how we can broaden the base, not shrink the base. As a conservative, I’m not looking to compromise principles at all.

In the context of the prolife plank, you have spoken of the Republican party as a “big tent.” There are two ways to take that. One is that it’s big enough to include everybody, even though we don’t always agree on every issue; the other is that the tent is big because we’re going to reduce our principles to banal statements with no real content.

I talk about the “prolife big tent.” I know where I stand; I know where the President stands; I know what the platform is going to be. The tent on the abortion issue is prolife. The overall tent is Republican—you have prolife Republicans and you have prochoice Republicans. I am not going to ride people out of the Republican party who happen to disagree with me on the issue of abortion. In fact, I want them to be included.

The Democrats are the ones who are actually excluding prolife Democrats and making them feel uncomfortable. You ought to go back and take a look at Pennsylvania Gov. Robert Casey’s recent speech to the National Press Club. He said, I am prolife and I’m feeling very uncomfortable in the Democratic party. They have a much bigger problem than we do.

There’s a great frustration that even though candidates who stand with evangelicals on key issues are elected, and evangelicals get invited to the White House, some key policies haven’t changed. Many evangelicals feel that having access is great, but this administration still invites homosexual activists to bill signings, and we’ve lost most of the religious-liberties issues, even in a Supreme Court made up largely of Reagan-Bush appointees. Aren’t we supposed to expect policies to be changed—particularly if we have an evangelical Christian Vice-president and a President who says he is born again?

I would hope that you don’t feel excluded, but I know that feeling is out there. I heard it recently. I talked to [Deputy Assistant to the President for Public Liaison] Leigh Ann Metzger and said, what are we doing to reach out to this community?

Do you know what the reaction here in Washington sometimes is? People here say, these are “our” people; they’re with us. People in the administration know where evangelicals stand. They know that on these issues we’re with you.

Take the recent debate about the National Endowment for the Arts. I was in the Oval Office when the President looked at some of this obscene stuff, and he was shocked. Now you know well enough that the President of the United States doesn’t know when grants go out from the NEA or the highway department or the agriculture department. But you should know that the President shares your values.