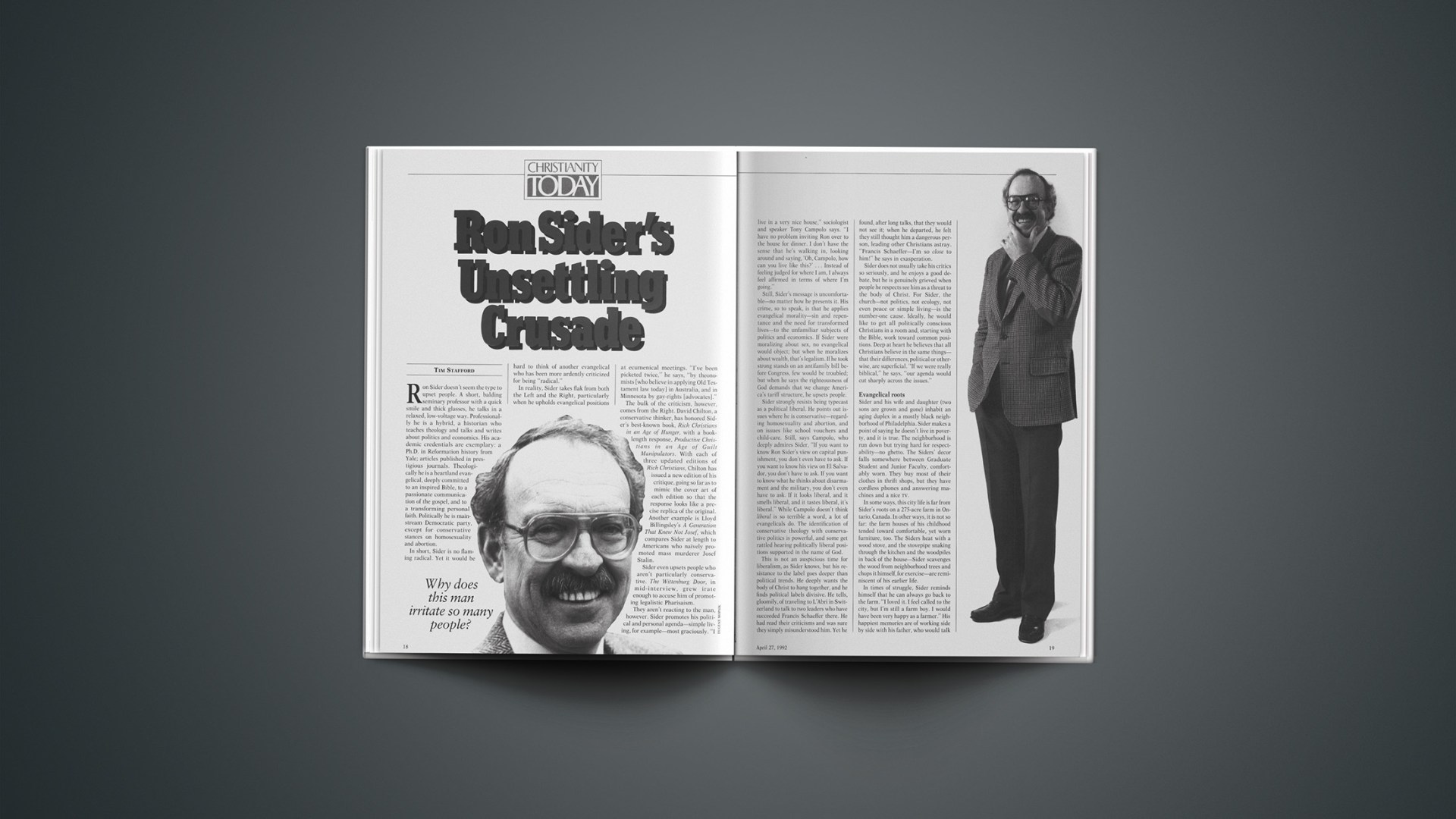

Ron Sider doesn’t seem the type to upset people. A short, balding seminary professor with a quick smile and thick glasses, he talks in a relaxed, low-voltage way. Professionally he is a hybrid, a historian who teaches theology and talks and writes about politics and economics. His academic credentials are exemplary: a Ph.D. in Reformation history from Yale; articles published in prestigious journals. Theologically he is a heartland evangelical, deeply committed to an inspired Bible, to a passionate communication of the gospel, and to a transforming personal faith. Politically he is mainstream Democratic party, except for conservative stances on homosexuality and abortion.

In short, Sider is no flaming radical. Yet it would be hard to think of another evangelical who has been more ardently criticized for being “radical.”

In reality, Sider takes flak from both the Left and the Right, particularly when he upholds evangelical positions at ecumenical meetings. “I’ve been picketed twice,” he says, “by theonomists [who believe in applying Old Testament law today] in Australia, and in Minnesota by gay-rights [advocates].”

The bulk of the criticism, however, comes from the Right. David Chilton, a conservative thinker, has honored Sider’s best-known book, Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger, with a book-length response, Productive Christians in an Age of Guilt Manipulators. With each of three updated editions of Rich Christians, Chilton has issued a new edition of his critique, going so far as to mimic the cover art of each edition so that the response looks like a precise replica of the original. Another example is Lloyd Billingsley’s A Generation That Knew Not Josef, which compares Sider at length to Americans who naïvely promoted mass murderer Josef Stalin.

Sider even upsets people who aren’t particularly conservative. The Wittenburg Door, in mid-interview, grew irate enough to accuse him of promoting legalistic Pharisaism.

They aren’t reacting to the man, however. Sider promotes his political and personal agenda—simple living, for example—most graciously. “I live in a very nice house,” sociologist and speaker Tony Campolo says. ‘I have no problem inviting Ron over to the house for dinner. I don’t have the sense that he’s walking in, looking around and saying, ‘Oh, Campolo, how can you live like this?’.… Instead of feeling judged for where I am, I always feel affirmed in terms of where I’m going.”

Still, Sider’s message is uncomfortable—no matter how he presents it. His crime, so to speak, is that he applies evangelical morality—sin and repentance and the need for transformed lives—to the unfamiliar subjects of politics and economics. If Sider were moralizing about sex, no evangelical would object; but when he moralizes about wealth, that’s legalism. If he took strong stands on an antifamily bill before Congress, few would be troubled; but when he says the righteousness of God demands that we change America’s tariff structure, he upsets people.

Sider strongly resists being typecast as a political liberal. He points out issues where he is conservative—regarding homosexuality and abortion, and on issues like school vouchers and child-care. Still, says Campolo, who deeply admires Sider, “If you want to know Ron Sider’s view on capital punishment, you don’t even have to ask. If you want to know his view on El Salvador, you don’t have to ask. If you want to know what he thinks about disarmament and the military, you don’t even have to ask. If it looks liberal, and it smells liberal, and it tastes liberal, it’s liberal.” While Campolo doesn’t think liberal is so terrible a word, a lot of evangelicals do. The identification of conservative theology with conservative politics is powerful, and some get rattled hearing politically liberal positions supported in the name of God.

This is not an auspicious time for liberalism, as Sider knows, but his resistance to the label goes deeper than political trends. He deeply wants the body of Christ to hang together, and he finds political labels divisive. He tells, gloomily, of traveling to L’Abri in Switzerland to talk to two leaders who have succeeded Francis Schaeffer there. He had read their criticisms and was sure they simply misunderstood him. Yet he found, after long talks, that they would not see it; when he departed, he felt they still thought him a dangerous person, leading other Christians astray. “Francis Schaeffer—I’m so close to him!” he says in exasperation.

Sider does not usually take his critics so seriously, and he enjoys a good debate, but he is genuinely grieved when people he respects see him as a threat to the body of Christ. For Sider, the church—not politics, not ecology, not even peace or simple living—is the number-one cause. Ideally, he would like to get all politically conscious Christians in a room and, starting with the Bible, work toward common positions. Deep at heart he believes that all Christians believe in the same things—that their differences, political or otherwise, are superficial. “If we were really biblical,” he says, “our agenda would cut sharply across the issues.”

Evangelical Roots

Sider and his wife and daughter (two sons are grown and gone) inhabit an aging duplex in a mostly black neighborhood of Philadelphia. Sider makes a point of saying he doesn’t live in poverty, and it is true. The neighborhood is run down but trying hard for respectability—no ghetto. The Siders’ decor falls somewhere between Graduate Student and Junior Faculty, comfortably worn. They buy most of their clothes in thrift shops, but they have cordless phones and answering machines and a nice TV.

In some ways, this city life is far from Sider’s roots on a 275-acre farm in Ontario, Canada. In other ways, it is not so far: the farm houses of his childhood tended toward comfortable, yet worn furniture, too. The Siders heat with a wood stove, and the stovepipe snaking through the kitchen and the woodpiles in back of the house—Sider scavenges the wood from neighborhood trees and chops it himself, for exercise—are reminiscent of his earlier life.

In times of struggle, Sider reminds himself that he can always go back to the farm. “I loved it. I feel called to the city, but I’m still a farm boy. I would have been very happy as a farmer.” His happiest memories are of working side by side with his father, who would talk over which crops to plant.

His father served as a pastor in the Brethren in Christ, an insular, rural denomination that combined elements of holiness, Anabaptist, and pietistic traditions. Sider remembers vividly the guilty struggle he had when he first decided to part his hair on the side, or to wear a tie—choices that were thought vain and worldly. He was converted to Christ in a revival meeting and seems to have little besides happy memories of his church upbringing. “I sometimes say I’ve been sanctified a dozen times, but it never quite took,” he says with a laugh. “But I very much appreciate that side of theology. I think the kind of easy way that mainstream Protestantism tolerates sin without hope of change is not New Testament. The Holy Spirit wants us to keep making progress, although it’s a process.”

Nevertheless, perfectionist expectations weren’t entirely easy to live with. Sider remembers feeling relieved, as a boy, hearing his dad swear when a prized cow died. “Then I knew he wasn’t fully sanctified.” As for his deeply spiritual mother, Sider says with a smile, he was never quite sure.

Sider attended a one-room country school a stone’s throw from home. His father had been the last pastor in their Ontario district selected—by lot—without at least a high-school education. He wanted his children to get what he had not gotten. Ron, the first-born son, was an outstanding student as well as a star athlete. (Hockey was his best and most beloved sport.) It seemed logical for him not only to graduate, but to go on to college. He proudly set off for nearby Waterloo Lutheran, the first in his family ever to attend college. Solemnly he bought a jacket and briefcase—expensive, by his standards—with the college name.

Waterloo was “a classic former Christian college—a few Christian profs still around, and a lot of secular people.” Planning to be a high-school history teacher, Sider met two outstanding mentors. The first was an invigorating, agnostic history professor who introduced him to “the standard intellectual doubts that come to anyone who has lived since the Enlightenment and knows what’s going on.” He also introduced him to social activism, leading him on his first protest march—a demonstration against the 1960 South African police massacre at Sharpeville.

His second mentor was a very different character, John Warwick Montgomery. An outspoken, contentious evangelical, Montgomery arrived in Sider’s junior year as chairman of the history department. He made no secret of his brilliance, nor of his belief that the Resurrection was part of history. Sider, who had begun to work his way out of doubt, found his faith braced and stimulated. He began to point toward graduate school with a new, emerging hope: to follow in Montgomery’s footsteps as a professor and apologist in the secular university. When, one day, he received a letter from Yale accepting him as a graduate student and awarding him a full fellowship, he dropped to his knees, “breathless with gratitude.” He, a farm boy proud to bursting of Waterloo College, would go off to study with the likes of Roland Bainton and Jaroslav Pelikan. He would carry the message of the historical Resurrection into the secular world.

U-Turn

Sider arrived at Yale feeling like the country bumpkin, not even knowing how to dress. His best and first friends there he describes as “Wheaton sophisticates” (a combination of words that might not occur to all Yale graduates). For the first time in his life, he was far from his roots and by no means certain he was capable of succeeding. But he did well academically, and, “wanting to feel the full force of the intellectual challenge,” did a theological degree at Yale Divinity School in addition to his Ph.D. in history. His doctoral thesis, on radical Reformer Karl Bodenstein von Karlstadt, was good enough to be published. In addition, Sider produced scholarly articles for prestigious journals on the subject of a historically credible Resurrection, developing Montgomery’s ideas.

He finds it frustratingly ironic that one of his conservative critics, Gary North, has painted him as an existentialist who does not believe in a historical Resurrection. “I want to insist on the importance of propositional revelation. I want to insist on the importance of reason in apologetics.”

During graduate school, Sider had anticipated a career teaching at a secular university, sponsoring an InterVarsity group, lecturing on the Resurrection. But then came a dramatic U-turn.

Except that it did not seem like a U-turn at the time. Sider received a letter from Messiah College, a small Christian school linked to his home denomination. They wanted to launch a branch in inner-city Philadelphia, affiliated with Temple University. They wondered whether he would be interested. “I was on the phone in ten minutes,” Sider remembers. His peers thought the decision strange, but Sider never doubted. The location fit his sense of call to social activism. The affiliation with Temple fit his theories about how to bring Christian ideas and nurture into the secular multiversity.

As it worked out, however, Messiah moved him from the secular challenges of a university. (He has since moved even further away, to Eastern Seminary.) Instead of publishing scholarly history, he began to write for popular audiences—indeed, Christian audiences. Instead of becoming an evangelist, he became a pastor—like his father. He began to apply his knowledge of theology and history to the problems of justice and poverty, and to the responses that Christians should make.

At Yale, he had been interested in social justice—had helped organize voter registration, and joined the NAACP. But at Messiah’s inner-city branch, urban issues were full-time. His two sons went to virtually all-black, ghetto schools. His wife—he had married a Mennonite farm girl, Arbutus Lichti, while in college—became involved in the Philadelphia school system. Soon she was helping to organize a politically active parents’ group, even leading marches to city hall.

Ron himself was Writing articles, organizing seminars for pastors, and launching Evangelicals for McGovern, a shoestring political organization that gained attention because of its manbites-dog name. That led to the Chicago Declaration of 1973, a well-publicized, nonpartisan statement favoring political and social involvement for evangelical Christians. Sider became a spark plug among a small group of evangelicals who were interested in social and political issues, most of whom were young, well educated, highly idealistic, and shared a concern for social and racial justice and simple living.

One of the earliest popular articles Sider wrote was for InterVarsity’s now-defunct His magazine. Sider was trying to deal practically with a peculiarly evangelical theme: how to respond to a societal problem—world poverty—through choices at a personal, household level. He advocated a graduated tithe. As income increased, Sider suggested, so should the percentage of charitable giving. The tithe would become like the pre-Reagan tax tables: all but confiscatory at the upper echelons, except that, of course, Sider emphasized joyful, voluntary giving.

The article attracted attention, and InterVarsity Press expressed interest in a book expanding the concept. With no great expectations, they released it in 1977. Yet it caught the spirit of the times, it sold strongly, and it changed the Siders’ lives.

Rich Christians

Rich Christians has sold more than a quarter-million copies—a remarkable record, considering how books on social justice generally sell. It continues to sell in its third edition.

The book details the tremendous difference between the rich industrial West and the poor Third World. It considers God’s concern for the poor and his anger against the unjust, complacent wealthy—a theme that is, as Sider demonstrates, highly biblical, though often neglected. Then Sider tries to analyze our contemporary situation. Why do so many starve while others have unprecedented wealth, and what does God expect us to do about it?

This is where Sider gets most uncomfortably practical, and where he has been most criticized. For Sider is not content to urge Christians to be fair in their personal dealings and generous in their giving. He takes up “structural evil”—the way in which injustice can be incorporated into a system, so that no one is really responsible, it’s “just the way things are.”

Here Sider’s book is both weakest and strongest. Sider is no economist, and as he pushes through such large issues as the international debt crisis, the structure of world trade, and global warming (in the latest, updated edition), he is not particularly convincing. As University of Michigan philosopher George Mavrodes wrote soon after Rich Christians was first issued, Sider shows little understanding that the economy is a system, and that you cannot simply change one facet of the system without introducing dozens of other unintended changes. Sider’s analysis draws from complaints voiced in many international forums, particularly by Third World and liberal economists, but he does not mention that they have been answered by conservatives.

The well-grooved debate goes approximately this way: Liberals assert that the world economic system is flawed, as proven by intolerable poverty, and suggest ways in which the system should be changed. Conservatives respond that while the situation may be bad, it might be a great deal worse, and that it is generally worst where governments attempt to intervene in free-market systems. Therefore, conservatives are skeptical about changing the system, especially where change involves new or expanded governmental powers. Liberals tend to look at the evils of poverty as a remarkable exception to the norm and hold the wealthy responsible for alleviating it; conservatives tend to look at the economic development of the West as the norm, and hold the poor responsible for not emulating it. The arguments tend to get a lot more technical from that point on. They certainly are not simple. It is not always clear why some nations have become wealthy and others remain poverty stricken; nor is it clear how the situation can be changed.

Sider clearly, if simplistically, presented the liberal side of this debate. That in itself would rankle some evangelicals, who regard anyone to the left of Jesse Helms as a doubtful Christian. But when Sider went further, when he made his views the basis for morality, he got some people’s goats. For example: “If God’s Word is true,” Sider wrote, “then all of us who dwell in affluent nations are trapped in sin. We have profited from systematic injustice.… We are guilty of an outrageous offense against God and neighbor.”

But, we might ask, what if our affluence is based not on robbery, but on national creativity, hard work, democratic values? What if God’s Word is true but Sider’s analysis is flawed?

Some critics charged Sider with being a socialist, which certainly is not true. He favors, in fact, localized decision making and widely dispersed ownership of property. “I’m a farm boy from Ontario,” he says, “and I don’t think you’ll find too many farmers who want the government to come in and take over.”

A fairer criticism is that, like many Americans, conservative and liberal, he exaggerates the significance of America’s role in the world. By his concentration on American faults, he seems to suggest that if it weren’t for us, there would be no world hunger.

If Sider is weakest in analyzing structural evil, he is also strongest there. In conversation he shows little dogmatism about any particular economic solution. He does stick tenaciously to Rich Christians’ troubling insistence that world economics is not just a technical discussion but a battleground for good and evil. Some people, he keeps reminding us, are so poor they are literally starving to death, while we, their neighbors, live in luxury. Poverty is a moral issue; it is an issue that God cares about fiercely. If we do not know how to change the situation, we should—must—try to learn. Sider shows a moral urgency that is missing in most analyses. His bringing sin into the language of world poverty is a uniquely evangelical contribution. If it gets under people’s skin, so be it. Their brothers and sisters are hungry.

New Generation

“I would like to take a little poll here,” Ron Sider says. He is in small-town Nebraska on an October morning, dressed in a light-blue suit, without a tie, speaking to about one hundred Evangelical Covenant pastors gathered for their annual Midwest retreat. “How many of you know, within 100 miles of your home, five congregations that are doing both evangelism and social concern in their local community, and doing it in a way that you admire?”

Nobody raises a hand. Sider repeats the question, asking for only three congregations, and then for only one congregation. A few hands go up.

“How many of you think that Jesus Christ wants his church to be enthusiastically doing both evangelism and social work?” Sider asks. Everyone’s hand goes up.

He goes on to tell of Mark, a young South African who “was literally afraid that if he became a Christian he would lose his passion for justice.” Sider convinced him that his passion could grow deeper if he followed Jesus. Sider describes how after praying with Mark he “walked around the room singing praises to the Lord.” Isn’t it possible, he asks, that there are others like Mark, who would like to come to Christ but hesitate because they have never seen Christians living out their concerns for justice? Is it possible that the church’s lack of social action is, in fact, an impediment to evangelism?

Then Sider tells of attending a meeting of the National Council of Churches, where dozens of workshops were offered on peacemaking, ecology, poverty, and injustice, but not one on evangelism. “I said to them, ‘How on earth can you be that one-sided? We evangelicals have been one-sided, and we’re working to correct that.’ ” Sider says he cannot imagine a comparable meeting of evangelicals that lacked a single workshop on social concern; how can liberal church leaders be so blind?

In a densely packed talk, Sider goes on to plead for a church where both evangelism and social action work symbiotically—evangelism creating the changed lives that are necessary to lasting social change, social action living out the good news of the gospel in a way that attracts outsiders.

More and more Sider finds himself talking and writing about the church. Not that he is any less interested in politics. He still sees “structural evil” behind much of the poverty and injustice of the world, and he is very much drawn to what happens in Washington. Evangelicals for Social Action (ESA), the organization he launched 18 years ago and still heads, puts much of its limited energy into analyzing congressional bills. But the group has only 3,200 members. With its mostly liberal politics in eclipse, ESA has not been able to mobilize a large constituency.

The years seem to have given Sider more humility about simple answers. At a World Council of Churches meeting in Seoul, Korea, he was dismayed that delegates seemed so much more interested in blaming the West for Third World poverty than in understanding how their Korean hosts had managed to lift their country out of poverty. In the third edition of Rich Christians, he notes, “In the first edition of this book, I said that social evil hurts more people than personal evil. That may be true in the Third World, but I no longer believe that it is true in North America and Western Europe.” The tide of promiscuity and divorce now seems to him far more significant. He says that “Tim LaHaye exaggerates in simplistic ways, but he’s right about secular humanism pushing religion out of the public concern.” Sider may not have grown more conservative, but he certainly has found points of agreement with his conservative critics.

That leaves him somewhat lonely. He is too cautious for the radical fringe of evangelicalism, represented by magazines like Sojourners and The Other Side. Yet he remains anathema to conservative activists, who dominate evangelical politics.

The key to understanding Ron Sider, though, is not his politics. It is his theology. Unlike the Religious Right, which has been mostly reactive, Sider’s political involvement has always been proactive. In reading the Bible, he saw that God cares about social and political life as well as personal piety. And so Sider sees his activities in terms of applying the Bible to life.

Sider’s holiness upbringing is embedded in his soul, which means he is at root an activist, someone who can never shrug and say, “That’s just the way life is.” Where he finds evil in his soul, he is going to struggle against it; where he sees evil in the world, he is going to call down heaven to fight it. The evil he sees did not originate with secular humanism. It is part of the ancient human battle between good and evil, selfishness and generosity—it is not particularly a fight between Republicans and Democrats. For Sider, political involvement is part of discipleship, and he is never going to quit.

It is helpful to remember, too, that Sider is a hockey player. He is a pacifist, but one who feels comfortable wielding an ax and a chain saw. He loves to fish, but friends who have been on his fishing expeditions say the purpose is not to commune with nature; Sider goes to catch fish.

Persistence is in Sider’s blood; his secretary reports that two hernia operations last year brought a remarkable change: it was the first time she had seen him walk slowly. Through 20 years of perpetual motion, he has helped to keep world poverty on evangelicals’ consciences. In another 20 years, if he stays in good health, we will still see him swinging his ax.