In this series

Martin Luther was many things: preacher, teacher, orator, translator, theologian, composer, and family man. He came to symbolize everything the Protestant Reformation stood for.

But perhaps Luther’s greatest achievement was the German Bible. No other work has had as strong an impact on a nation’s development and heritage as has this Book.

In Luther’s time, the German language consisted of several regional dialects (all similar to the tongue spoken in the courts of the Hapsburg and Luxemburg emperors). How were these scattered dialects united into one modern language? The rise of the middle class, the growth of trade, and the invention of the printing press all played a part. But the key factor was Luther’s Bible.

The Wartburg Wonder

Following the Diet of Worms in 1521, Luther’s territorial ruler, Frederick the Wise, had Luther hidden away for safekeeping in the castle at Wartburg. Luther settled down and translated Erasmus’s Greek New Testament in only eleven weeks. This is a phenomenal feat under any circumstances, but Luther contended with darkened days, poor lighting, and his own generally poor health.

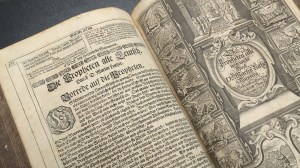

Das Newe Testament Deutzsch was published in September 1522. A typographical masterpiece, containing woodcuts from Lucas Cranach’s workshop and selections from Albrecht Durer’s famous Apocalypse series, the September Bibel sold an estimated five thousand copies in the first two months alone.

Luther then turned his attention to the Old Testament. Though well taught in both Greek and Hebrew, he would not attempt it alone. “Translators must never work by themselves,” he wrote. “When one is alone, the best and most suitable words do not always occur to him.” Luther thus formed a translation committee, which he dubbed his “Sanhedrin.” If the notion of a translation committee seems obvious today, it is because such scholars as Philipp Melanchthon, Justus Jonas, John Bugenhagen, and Caspar Cruciger joined Luther in setting the precedent. Never before, and not for many years after, was the scholarship of this body equaled.

Forcing Prophets to Speak German

Luther remained the principal translator, however. His spirit motivated and guided the Sanhedrin in producing a translation that was not literal in the truest sense of the word. He wanted this Bible to be in spoken rather than bookish or written German. Before any word or phrase could be put on paper, it had to pass the test of Luther’s ear, not his eye. It had to sound right. This was the German Bible’s greatest asset, but it meant Luther had to straddle the fence between the free and the literal.

“It is not possible to reproduce a foreign idiom in one’s native tongue,” he wrote. “The proper method of translation is to select the most fitting terms according to the usage of the language adopted. To translate properly is to render the spirit of a foreign language into our own idiom. I try to speak as men do in the market place. In rendering Moses, I make him so German that no one would suspect he was a Jew.”

The translators used the court tongue as their base language but flavored it with the best of all the dialects they could find in the empire. Luther, a relentless perfectionist who might spend a month searching out a single word, talked at length with old Germans in the different regions. To better understand the sacrificial rituals in the Mosaic law, he had the town butcher cut up sheep so he could study their entrails. When he ran into the precious stones in the “new Jerusalem” that were unfamiliar to him, he had similar gems from the elector’s collection brought for him to study.

Luther longed to express the original Hebrew in the best possible German, but the task was not without its difficulties. “We are now sweating over a German translation of the Prophets,” he wrote. “O God, what a hard and difficult task it is to force these writers, quite against their wills, to speak German. They have no desire to give up their native Hebrew in order to imitate our barbaric German. It is as though one were to force a nightingale to imitate a cuckoo, to give up his own glorious melody for a monotonous song he must certainly hate. The translation of Job gives us immense trouble on account of its exalted language, which seems to suffer even more, under our attempts to translate it, than Job did under the consolation of his friends, and seems to prefer to lie among the ashes.”

In spite of this, the Sanhedrin worked rapidly but accurately, translating in a tone more apologetic than scientific. The result was a German Bible of such literary quality that those competent to say so consider it superior even to the King James Version that followed it. And because it sounded natural when spoken as well as read, its cadence and readability have made it a popular Bible in Germany to this day.

The Book Must Be in German Homes

Germans everywhere bought Luther’s Bible, not only for the salvation of their souls (if such was their concern), but also for the new middleclass prestige it conferred. It was the must book to have in their homes, and many Germans had no choice but to read it: it was likely to be one of the few books they could afford to buy.

It was the first time a mass medium had ever penetrated everyday life. Everyone read Luther’s new Bible or listened to it being read. Its phrasing became the people’s phrasing, its speech patterns their speech patterns. So universal was its appeal, and so thoroughly did it embrace the entire range of the German tongue, that it formed a linguistic rallying point for the formation of the modern German language. It helped formally restructure German literature and the German performing arts. Its impact, and Luther’s in general, were so awesome that Frederick the Great later called Luther the personification of the German national spirit. Many scholars still consider him the most influential German who ever lived.

Uncle of the English Bible

As might be expected, the German Bible’s impact reached well beyond the borders of the empire. It was the direct source for Bibles in Holland, Sweden, Iceland, and Denmark, and its influence was felt in many other countries as well.

Most important, the Bible left a permanent impression on a great translator of the English Bible. William Tyndale, one of the Reformation’s champions, had fled from England to the Continent about the time Luther was publishing his German New Testament. He, too, was translating from the original manuscripts, and possibly he and Luther met in Wittenberg.

One strong point of Luther’s work that impressed Tyndale was the order given to the books of the New Testament. In previous Bibles, there had been no uniform arrangement; translators placed them in whatever order suited them.

Luther, however, ranked them by the yardstick of was treibt Christus—how Christ was taught: the four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John); the Acts of the Apostles; the Epistles, in descending order of the Savior’s prominence in each; and, finally, the Revelation of John. Tyndale followed Luther’s lead, as have virtually all Bible translators since.

Many phrases we know today came from Luther, through Tyndale. From the German’s natürlich, Tyndale wrote natural, and the phrase natural man appeared in 1 Corinthians 2:14. Luther’s auf dem gebirge became was a voice heard in Matthew 2:18. Tyndale translated from Luther the place of dead men’s skulls in John 19:17, Ye vex yourselves off a true meaning in 2 Corinthians 6:12, Doctors in the Scripture in 1 Timothy 1:7, and hosianna in Matthew 21:15.

Like Luther, Tyndale eschewed the Latinized ecclesiastical terms in favor of those applicable to his readers: repent instead of do penance; congregation rather than church; Savior or elder in the place of priest; and love over charity for the Greek agape.

Both translations flowed freely in a rhythm and happy fluency of narration; and, wherever he could, Tyndale upheld Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith. While in many instances the two translators must have reached the same conclusions independently, Luther’s strong influence on the father of the English Bible is unmistakable. Since Tyndale’s English translation makes up more than 90 percent of the King James New Testament and more than 75 percent of the Revised Standard Version, Luther’s legacy is still plain to see.

Luther was exceptionally gifted in many areas. But the aspect of his genius perhaps most responsible for his impact is the one least heralded: his skill and power as a translator and writer. Had it not been for that, the Protestant Reformation and the growth of a united German nation might have taken an entirely different course.

Henry Zecher is a personnel specialist at the U. S. Department of Health & Human Resources. Formerly, he wrote for the Delaware State News.

Copyright © 1992 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.