Draped in a white sweater, a straw hat strapped to her hip, Nellie Beel does not look the part of a radical. At 73, she more closely resembles the woman in Grant Wood’s American Gothic painting, except with a wonderfully graceful smile. But Beel, a St. Louis resident for 53 years, is radical when it comes to one thing.

“I love to advertise Jesus,” Beel said as she stood on a St. Louis street, clasping a sign that read, “No one ever cared for you like Jesus.”

“Anything that will get people’s attention toward the Lord,” she said. “Any honest way to get people’s attention.”

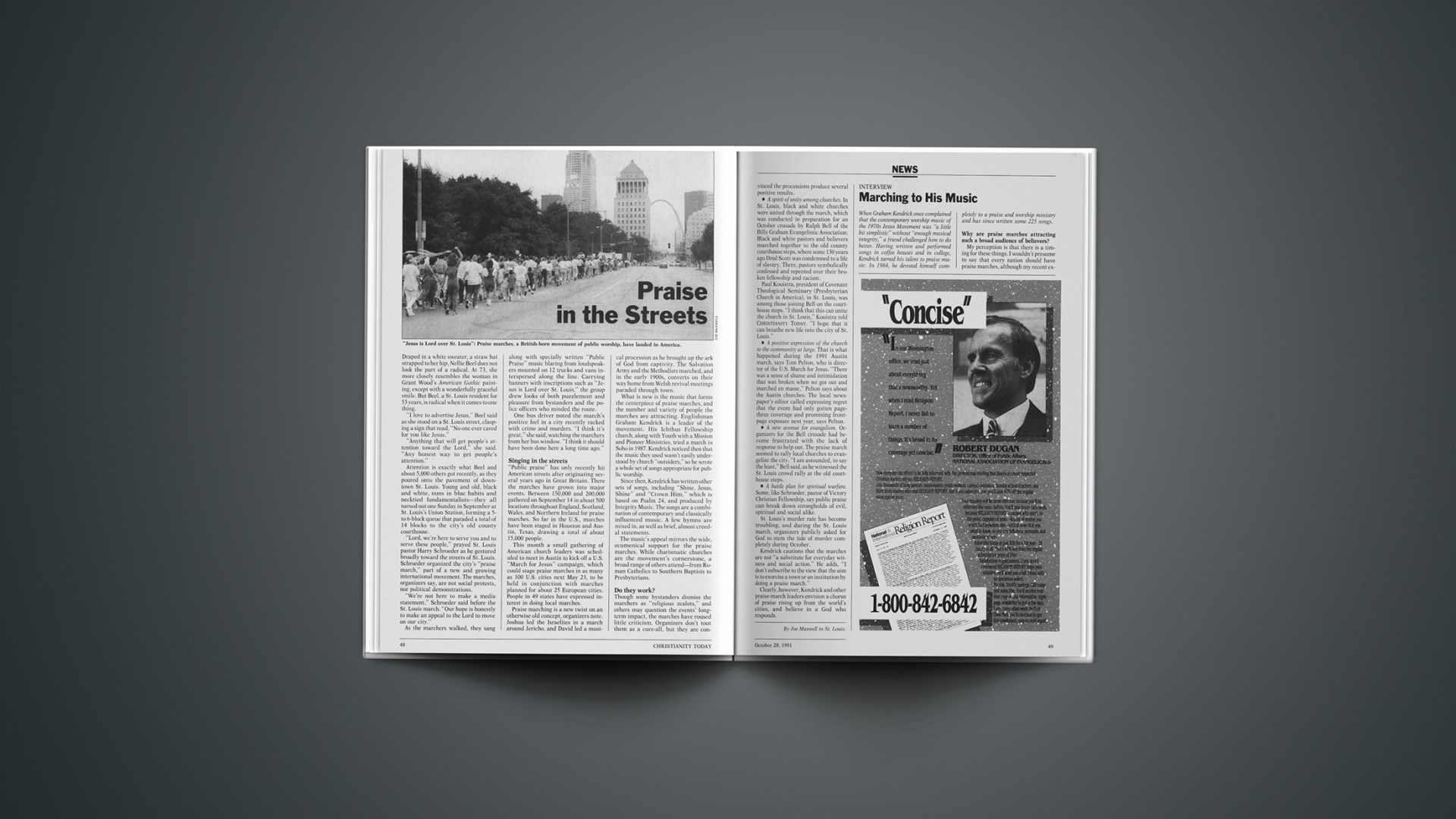

Attention is exactly what Beel and about 5,000 others got recently, as they poured onto the pavement of downtown St. Louis. Young and old, black and white, nuns in blue habits and necktied fundamentalists—they all turned out one Sunday in September at St. Louis’s Union Station, forming a 5-to 6-block queue that paraded a total of 14 blocks to the city’s old county courthouse.

“Lord, we’re here to serve you and to serve these people,” prayed St. Louis pastor Harry Schroeder as he gestured broadly toward the streets of St. Louis. Schroeder organized the city’s “praise march,” part of a new and growing international movement. The marches, organizers say, are not social protests, nor political demonstrations.

“We’re not here to make a media statement,” Schroeder said before the St. Louis march. “Our hope is honestly to make an appeal to the Lord to move on our city.”

As the marchers walked, they sang along with specially written “Public Praise” music blaring from loudspeakers mounted on 12 trucks and vans interspersed along the line. Carrying banners with inscriptions such as “Jesus is Lord over St. Louis,” the group drew looks of both puzzlement and pleasure from bystanders and the police officers who minded the route.

One bus driver noted the march’s positive feel in a city recently racked with crime and murders. “I think it’s great,” she said, watching the marchers from her bus window. “I think it should have been done here a long time ago.”

Singing In The Streets

“Public praise” has only recently hit American streets after originating several years ago in Great Britain. There the marches have grown into major events. Between 150,000 and 200,000 gathered on September 14 in about 500 locations throughout England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland for praise marches. So far in the U.S., marches have been staged in Houston and Austin, Texas, drawing a total of about 15,000 people.

This month a small gathering of American church leaders was scheduled to meet in Austin to kick off a U.S. “March for Jesus” campaign, which could stage praise marches in as many as 100 U.S. cities next May 23, to be held in conjunction with marches planned for about 25 European cities. People in 49 states have expressed interest in doing local marches.

Praise marching is a new twist on an otherwise old concept, organizers note. Joshua led the Israelites in a march around Jericho, and David led a musical procession as he brought up the ark of God from captivity. The Salvation Army and the Methodists marched, and in the early 1900s, converts on their way home from Welsh revival meetings paraded through town.

What is new is the music that forms the centerpiece of praise marches, and the number and variety of people the marches are attracting. Englishman Graham Kendrick is a leader of the movement. His Ichthus Fellowship church, along with Youth with a Mission and Pioneer Ministries, tried a march in Soho in 1987. Kendrick noticed then that the music they used wasn’t easily understood by church “outsiders,” so he wrote a whole set of songs appropriate for public worship.

Since then, Kendrick has written other sets of songs, including “Shine, Jesus, Shine” and “Crown Him,” which is based on Psalm 24, and produced by Integrity Music. The songs are a combination of contemporary and classically influenced music. A few hymns are mixed in, as well as brief, almost creedal statements.

The music’s appeal mirrors the wide, ecumenical support for the praise marches. While charismatic churches are the movement’s cornerstone, a broad range of others attend—from Roman Catholics to Southern Baptists to Presbyterians.

Do They Work?

Though some bystanders dismiss the marchers as “religious zealots,” and others may question the events’ long-term impact, the marches have roused little criticism. Organizers don’t tout them as a cure-all, but they are convinced the processions produce several positive results.

• A spirit of unity among churches. In St. Louis, black and white churches were united through the march, which was conducted in preparation for an October crusade by Ralph Bell of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Black and white pastors and believers marched together to the old county courthouse steps, where some 130 years ago Dred Scott was condemned to a life of slavery. There, pastors symbolically confessed and repented over their broken fellowship and racism.

Paul Kooistra, president of Covenant Theological Seminary (Presbyterian Church in America), in St. Louis, was among those joining Bell on the courthouse steps. “I think that this can unite the church in St. Louis,” Kooistra told CHRISTIANITY TODAY. “I hope that it can breathe new life into the city of St. Louis.”

• A positive expression of the church to the community at large. That is what happened during the 1991 Austin march, says Tom Pelton, who is director of the U.S. March for Jesus. “There was a sense of shame and intimidation that was broken when we got out and marched en masse,” Pelton says about the Austin churches. The local newspaper’s editor called expressing regret that the event had only gotten page-three coverage and promising front-page exposure next year, says Pelton.

• A new avenue for evangelism. Organizers for the Bell crusade had become frustrated with the lack of response to help out. The praise march seemed to rally local churches to evangelize the city. “I am astounded, to say the least,” Bell said, as he witnessed the St. Louis crowd rally at the old courthouse steps.

• A battle plan for spiritual warfare. Some, like Schroeder, pastor of Victory Christian Fellowship, say public praise can break down strongholds of evil, spiritual and social alike.

St. Louis’s murder rate has become troubling, and during the St. Louis march, organizers publicly asked for God to stem the tide of murder completely during October.

Kendrick cautions that the marches are not “a substitute for everyday witness and social action.” He adds, “I don’t subscribe to the view that the aim is to exorcise a town or an institution by doing a praise march.”

Clearly, however, Kendrick and other praise-march leaders envision a chorus of praise rising up from the world’s cities, and believe in a God who responds.

By Joe Maxwell in St. Louis.