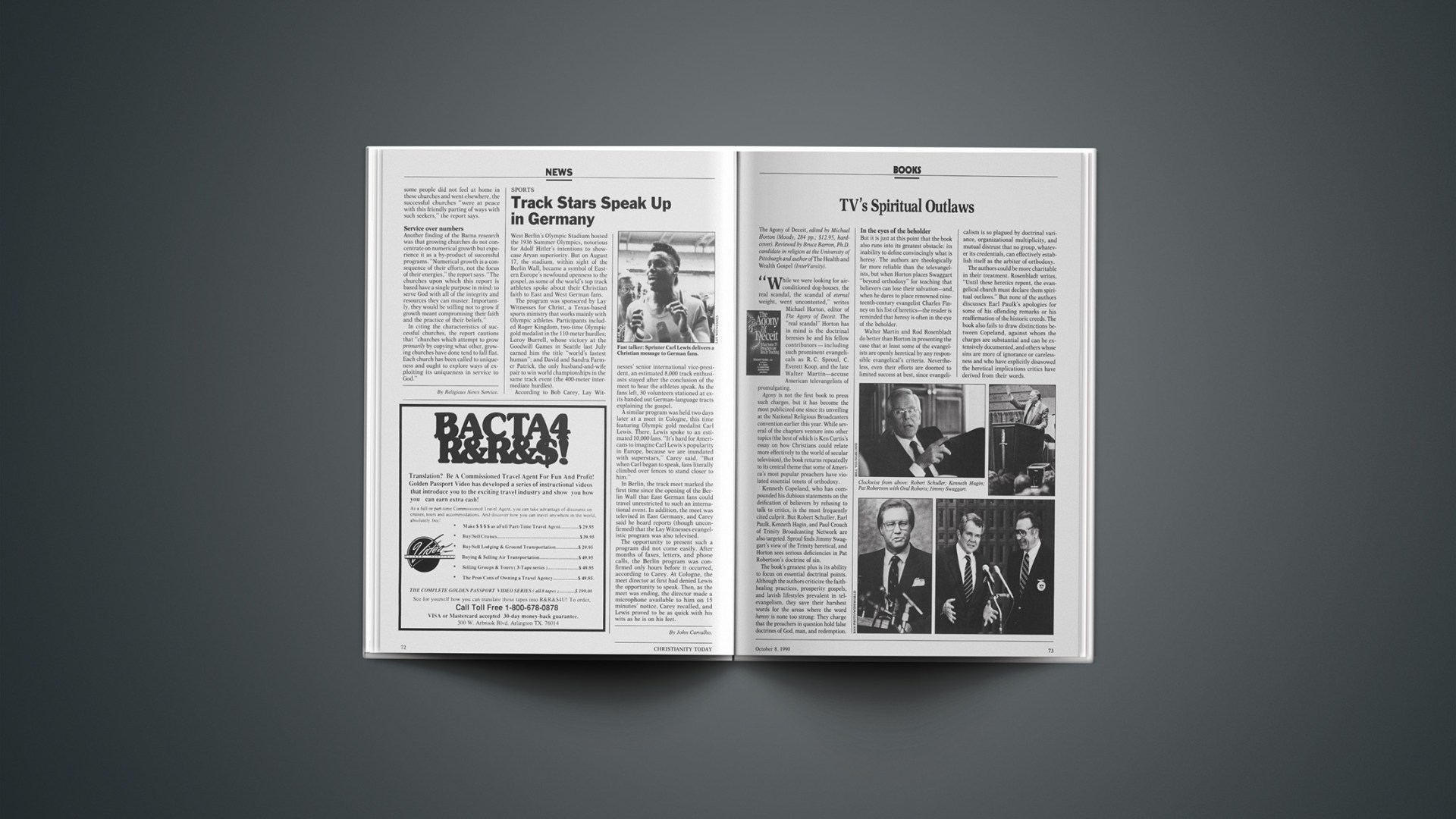

TV’s Spiritual Outlaws

The Agony of Deceit, edited by Michael Horton (Moody, 284 pp.; $12.95, hardcover). Reviewed by Bruce Barron, Ph.D. candidate in religion at the University of Pittsburgh and author of The Health and Wealth Gospel (InterVarsity).

“While we were looking for air-conditioned dog-houses, the real scandal, the scandal of eternal weight, went uncontested,” writes Michael Horton, editor of The Agony of Deceit. The “real scandal” Horton has in mind is the doctrinal heresies he and his fellow contributors—including such prominent evangelicals as R. C. Sproul, C. Everett Koop, and the late Walter Martin—accuse American televangelists of promulgating.

Agony is not the first book to press such charges, but it has become the most publicized one since its unveiling at the National Religious Broadcasters convention earlier this year. While several of the chapters venture into other topics (the best of which is Ken Curtis’s essay on how Christians could relate more effectively to the world of secular television), the book returns repeatedly to its central theme that some of America’s most popular preachers have violated essential tenets of orthodoxy.

Kenneth Copeland, who has compounded his dubious statements on the deification of believers by refusing to talk to critics, is the most frequently cited culprit. But Robert Schuller, Earl Paulk, Kenneth Hagin, and Paul Crouch of Trinity Broadcasting Network are also targeted. Sproul finds Jimmy Swaggart’s view of the Trinity heretical, and Horton sees serious deficiencies in Pat Robertson’s doctrine of sin.

The book’s greatest plus is its ability to focus on essential doctrinal points. Although the authors criticize the faith-healing practices, prosperity gospels, and lavish lifestyles prevalent in televangelism, they save their harshest words for the areas where the word heresy is none too strong: They charge that the preachers in question hold false doctrines of God, man, and redemption.

In The Eyes Of The Beholder

But it is just at this point that the book also runs into its greatest obstacle: its inability to define convincingly what is heresy. The authors are theologically far more reliable than the televangelists, but when Horton places Swaggart “beyond orthodoxy” for teaching that believers can lose their salvation—and when he dares to place renowned nineteenth-century evangelist Charles Finney on his list of heretics—the reader is reminded that heresy is often in the eye of the beholder.

Walter Martin and Rod Rosenbladt do better than Horton in presenting the case that at least some of the evangelists are openly heretical by any responsible evangelical’s criteria. Nevertheless, even their efforts are doomed to limited success at best, since evangelicalism is so plagued by doctrinal variance, organizational multiplicity, and mutual distrust that no group, whatever its credentials, can effectively establish itself as the arbiter of orthodoxy.

The authors could be more charitable in their treatment. Rosenbladt writes, “Until these heretics repent, the evangelical church must declare them spiritual outlaws.” But none of the authors discusses Earl Paulk’s apologies for some of his offending remarks or his reaffirmation of the historic creeds. The book also fails to draw distinctions between Copeland, against whom the charges are substantial and can be extensively documented, and others whose sins are more of ignorance or carelessness and who have explicitly disavowed the heretical implications critics have derived from their words.

A final irony arises in Horton’s concluding chapter: Having condemned the doctrines that our salvation, healing, and well-being depend on us rather than on God, he now states that exposing error in the church depends on us. Repudiating the pacifism of those who see the false teachers’ errors but say, “Let the Lord take care of it,” Horton replies that “God takes care of it through our responsible, loving, but bold confrontation.” This call to action is quite proper, but it suggests that some of his previous condemnations may have oversimplified the unavoidably paradoxical relationship between divine sovereignty and human responsibility.

The arguments presented in Agony require such close, even nitpicking scrutiny because the book’s thesis is so significant: If these authors are right, then a group of wolves in sheep’s clothing is leading a substantial portion of the evangelical church to the brink of eternal perdition. Even if the thesis is overstated, the book stands as an important manifesto calling evangelicals to recover the lost art of theological discernment.

Generally free from denominational accountability, the independent evangelists are unlikely to clean up their act doctrinally unless their financial support threatens to dry up. Their supporters, unfortunately, are not likely to read this book. But if The Agony of Deceit can in any way push these evangelists toward greater theological responsibility, it will have done the body of Christ a great service.

The Father And The Goddess

Women and Early Christianity: A Reappraisal, by Susanne Heine, trans. John Bowden (Augsburg, 182 pp.; $12.95, paper). Matriarchs, Goddesses, and Images of God: A Critique of a Feminist Theology, by Susanne Heine, trans. John Bowden (Augsburg, 183 pp.; $12.95, paper). Reviewed by Donald G. Bloesch, professor of theology, University of Dubuque Theological Seminary.

In these two provocative books, Susanne Heine, an ordained Lutheran minister and professor of theology at the University of Vienna, offers a penetrating critique of feminist theology.

What makes her appraisal particularly valuable and credible is that she speaks as one who stands partly within the women’s movement, fully identifying with the goals of dignity and justice for women as well as for men. Like feminist theologians, she seeks to purge all forms of sexism from the life of the church, not hesitating to criticize church tradition for its complicity in denying to women the freedom to realize a vocation of Christian ministry and service. She believes, however, that the turn toward goddess spirituality is a profound mistake that threatens to undo the solid gains women have made within the church and society in the past several decades.

Heine has deep misgivings concerning the trend toward inclusive God-language. She shows that the use of Father is integral to the message of faith. It was particularly necessary in biblical times to guard against the encroachment of the fertility cults in which female deities played a major role. While acknowledging the feminine dimension of the sacred, Heine nonetheless opts for the biblical way of assimilating maternal metaphors into a religion of strict monotheism.

She recognizes that the human experience of fatherhood has not always been benign, especially for many women, but insists that this is all the more reason to emphasize the uniqueness of God’s fatherhood, which stands in judgment over all fathers who claim a godlike authority. A truly transcendent God, therefore, holds much more promise for women and men engaged in the struggle for social justice than a God of radical immanence.

Heine is fully convinced that Paul has unjustly been made a scapegoat by feminist theologians. While he wrote within the context of a patriarchal culture, his message provided the catalyst for the liberation of both women and men. She can find no evidence of hostility toward either the body or women in Paul.

Interestingly, Heine contends that women in the apostolic church were actively involved in Christian ministry. They served as “apostles, deacons, community leaders, teachers and prophets. They travelled as missionaries and did charitable work; they preached, taught, gathered the believers together and sewed clothes for women.” The way they fulfilled their Christian vocation varied little from that of their male colleagues. But as the church accommodated itself to the surrounding patriarchal culture, it began to relegate women to subordinate positions in both the church and family.

Heine is thoroughly conversant with historical-critical studies, and she freely makes use of higher criticism to show how many feminist theologians are dishonest in the way they use the Bible to promote the cause of women. Occasionally she plays Scripture against Scripture, and perhaps too readily accepts the latest theories of critical scholarship concerning the authorship and dates of various books in the Bible.

Nonetheless, evangelicals as well as liberals could profit from a serious study of her books, for she presents a voice of moderation and good sense that is not often heard in the debates on inclusive God-language and women in ministry. While clearly on the side of orthodoxy in its battle with gnosticism and other heretical movements in the early church, she is emphatic that “the rise of heretical groups is always a sign that orthodoxy has become heretical.” The current fascination with goddess spirituality is evidence that an imbalance has existed within the church in which a patriarchal orientation has regrettably downgraded and ignored women’s contributions. Heine boldly calls for an alliance of women and men to work together to articulate a theology that is sensitive to the issues of social justice as well as faithful to God’s self-revelation in Jesus Christ as we find this in the Bible.

Can Protestants Worship?

Protestant Worship: Traditions in Transition, by James F. White (Westminster/John Knox, 251 pp.; $15.95, paper). Reviewed by Robert Webber, professor of theology at Wheaton College (Ill.).

The revival of Christian worship, which began in the Catholic church in the late nineteenth century, has now spread to nearly every denomination in the world. In this century, more books on worship have been written than in all the preceding centuries put together. Yet nearly all of these books have dealt with how pre-Reformation models of worship can relate to current renewal.

Now, however, Methodist liturgist and scholar James White has written Protestant Worship to explain and defend Protestant traditions. White, author of numerous books and articles on worship and professor of liturgies at Notre Dame, presents the characteristics of nine traditions: Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptist, Anglican, Separatist and Puritan, Quaker, Methodist, Frontier, and Pentecostal.

Breaking from the tradition of examining worship through Eucharistic texts, White proposes that Protestantism, which does not have a history of written Eucharistic texts, is best studied by paying attention to “the total event of public worship as it occurs in local churches.” The primary ingredient is people: people who have a piety that they bring to worship at a particular time, in a particular place. Furthermore, these people, when they gather for worship, pray, preach, and sing in a particular way. Through the study of these categories of worship, which both engage the people’s worship and express their action of worship, White carefully leads the reader into a recovery of the roots of these nine traditions of Protestant worship.

Using medieval Catholic worship as the central source from which these traditions derived, White classifies Protestant worship from right-wing worship (closest to the Catholic tradition) to central and left-wing (furthermost from Catholic worship). It is no surprise that right-wing worship includes Anglican and Lutheran; central worship is found in Reformed and Methodist; and left-wing worship is expressed in the Anabaptist, Quaker, Puritan, Frontier, and Pentecostal traditions.

With these categories in mind, White proceeds adroitly to describe each of the traditions as they emerge in history and as they have developed through the centuries. His entire analysis is historical and not theological. He deals with each tradition as an impassioned observer, making no judgment against any of the models. He clearly defends the right of each model to exist as a true model of worship and invites the reader to affirm that the worship of God really does occur in each tradition.

This nonvalue-oriented approach to the various traditions of Protestant worship leads White into several conclusions that are bound to be controversial. First, he asserts that “the lack of a strong sacramental life does not seem to vitiate the vigor or intensity of a worship tradition.” Second, in Protestant worship “the general direction has been to more possibilities for active participation and to greater amounts of it.” Third, “identical forms of worship for all western Christians would be deplorable achievement.” And finally, “the origination of new traditions of worship has not come to an end.”

Protestant Worship is a fine contribution to the study of worship and is bound to become the standard resource for an understanding of the various approaches Protestants have taken to worship. This accomplishment is no small feat, considering the difficulty of gathering information from traditions of worship that do not preserve their history through written texts.

While I greatly appreciate the historical nature of Protestant Worship, I would like to have seen more concern for the theological aspects of worship: How does each tradition define worship? What theological sense does each tradition make of its order of worship? What theological writings reflect its view of the sacraments, of written or extemporaneous prayer, of preaching, invitation, and spatial matters? In all fairness, however, it must be realized that the theological question requires another book and that the purpose of this writing was historical, not theological.

Finally, let it be stated that this masterpiece lifts the issue of worship out of the practical department where it never belonged (at least in the way worship is generally treated in seminaries), and highlights worship as a historical discipline. It is also, of course, a biblical, theological, environmental, and artistic discipline. I hope Professor White’s book will make its way into our Protestant seminaries and assist both professors and seminarians to recognize the need for the discipline of liturgies in the seminary curriculum.

But it is not a book written only for seminarians. It contains valuable information for pastors and members of a worship committee who want to understand their own tradition and how it compares to other Protestant traditions. For worship renewal in a local church is best born out of respect to one’s tradition—and, heaven knows, most congregations know precious little about their own historical roots.

Can International Politics Be Christian?

Evangelicals and Foreign Policy: Four Perspectives, edited by Michael Cromartie (Ethics and Public Policy Center, 89 pp.; $10.25, paper); A World Without Tyranny: Christian Faith and International Politics, by Dean C. Curry (Crossway, 256 pp.; $9.95, paper). Reviewed by Doug Bandow, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute and the author of The Politics of Plunder: Misgovernment in Washington (Transaction).

“On the face of it, the idea that there is a close connection between evangelical Christianity and the complex world of foreign policy seems strained if not ludicrous,” writes sociologist James Davison Hunter, a contributor to Evangelicals and Foreign Policy. After all, he asks, “what possible relevance could this particular form of Protestantism have to the complex relations between nations?”

It is a good question, one that he and Dean Curry, a professor at Messiah College; Alberto Coll, formerly a professor at the U.S. Naval War College who is now making policy at the Department of Defense; and theologian Richard John Neuhaus attempt to answer. These four essays, explains editor Michael Cromartie, are intended to survey the “history, current context, and dominant trends” of “evangelical involvement in foreign policy.”

Is there a uniquely Christian perspective regarding international relations? “The Bible is not a manual of foreign policy,” Curry writes, but it does set forth some guiding principles, such as opposition to racism, terrorism, and tyranny. To turn such principles into policy requires reliance on prudence, which Curry calls “a Biblically-grounded Christian virtue” involving “the careful, discerning weighing of competing means and ends.”

Similar in scope are the ten theses of “Christian realism” advanced by Alberto Coll. His is not an ideology of might makes right, but rather an attempt to resolve complex issues while recognizing “that man and his institutions stand under God’s judgment.” This does not mean that America is the chosen nation, Curry argues, a notion that lacks scriptural support and risks confusing national politics with the kingdom of God. Also flawed is the left’s failure to distinguish between highly imperfect and systematically evil political systems and its treatment of the U.S. as the Great Satan. Speaking to this issue is Richard John Neuhaus. The notion of “moral equivalence” between democratic and undemocratic states, he warns, “frequently results in Christians serving as apologists for present and future oppressors.”

Interventionalist Temptation

Curry expands on his thesis and tackles even more issues in A World Without Tyranny, a book that is prescriptive as well as descriptive. Some branches of Christianity have long had much to say about foreign policy. Even today, the Vatican is treated as a sovereign state. But modern evangelicalism, writes Curry, has been badly split between those who have “shunned any involvement with global politics,” those who have “somewhat uncritically identified the interest of the Church with the interests of the nation,” and those who have treated the U.S. as “an unjust society with injustices reflected in a malevolent foreign policy.”

All three of these perspectives are wrong, argues Curry. Particularly valuable is his warning against the “tendency to denigrate earthly endeavors.” God created the earth and placed Christians on it: “Rather than flee this world, Biblical obedience demands that we engage it.”

What does a prudential, realistic policy look like? Curry’s analysis here is, unfortunately, the weakest section of World Without Tyranny. One problem is simply that the world’s rapid changes have outpaced his book.

Moreover, his argument reflects the “interventionalist temptation,” the notion that the U.S. has an obligation to use its power to advance what it sees as moral ends. Yet the civil government was constituted to protect Americans’ security, not to promote abstract moral objectives, however high-minded. This distinction is particularly important since government action involves coercing one’s fellow citizens. Did, for example, the goal of preventing a northern takeover of South Vietnam justify drafting young Americans and consigning 58,000 to their deaths? The means as well as the ends must be moral.

Prudence may also counsel against intervention. Curry suggests that we might have better “accepted the Shah [of Iran] as a lesser of evils.” But should not the analysis go back to 1953, when the U.S. could have accepted leftist premier Muhammed Mussadegh “as a lesser of evils” rather than using the CIA to help replace him with the brutal shah?

Nevertheless, Curry’s book remains an important contribution to the debate over Christians’ responsibilities in the public square. We should be involved—“a Biblical faith is an active faith,” he writes—and A World Without Tyranny helps us understand how. So too does the Cromartie volume, which, although more limited in scope, highlights the thinking of four leading evangelical scholars.