Much of the real business transacted in downtown Minneapolis happens high above the snow, the exhaust, the dirt, and the blaring horns. Fifteen feet above the clamor, dressed-for-success businessmen and -women move quietly between offices and past gleaming chrome and bright, neoned boutiques. Many consider Minneapolis’s skyways—glass-walled passenger bridges linking office buildings and stores—a marvel of urban design. Cafés, parklike benches, and ice-cream vendors give the enclosed walkways the atmosphere of an old-fashioned commons.

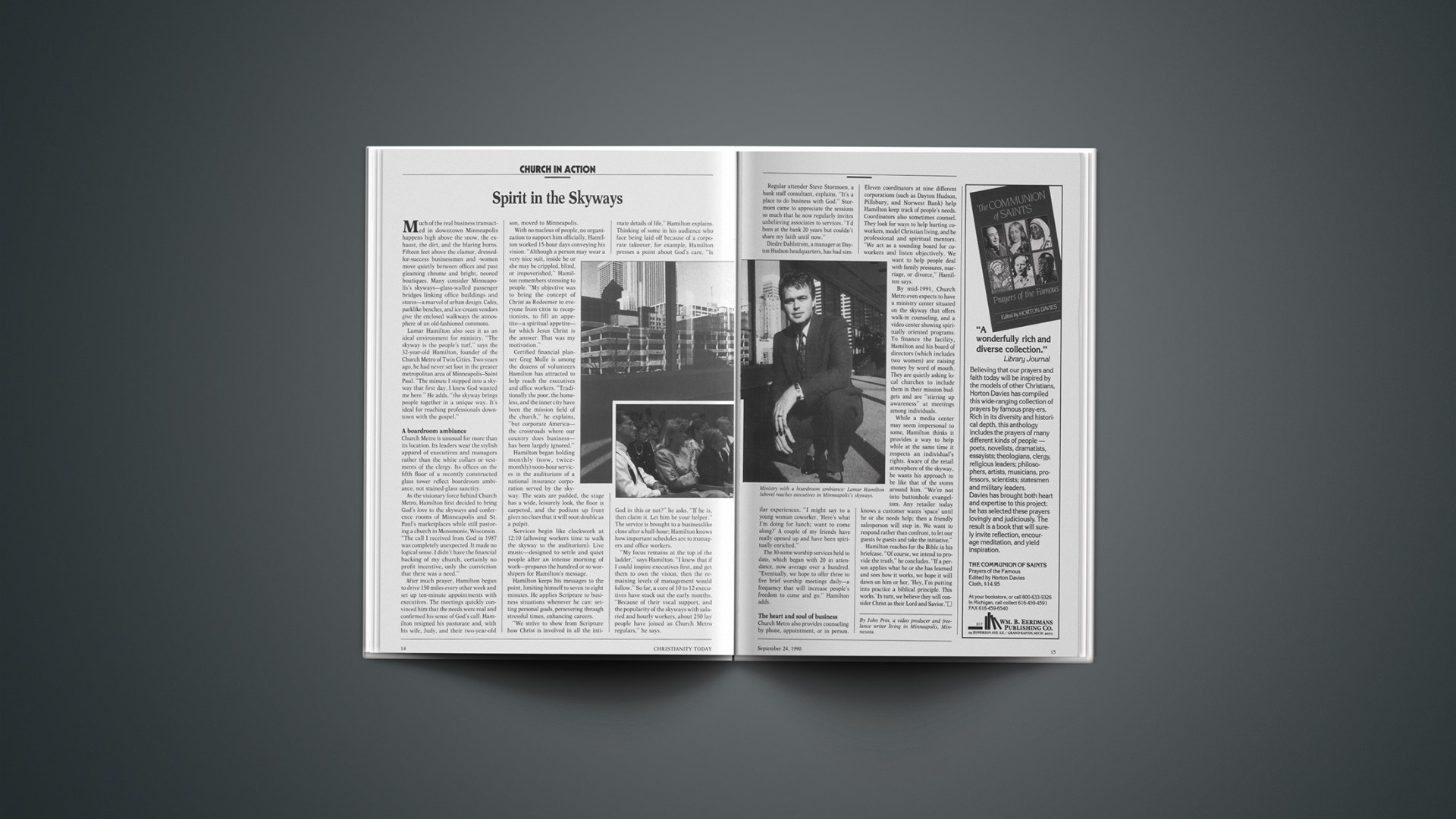

Lamar Hamilton also sees it as an ideal environment for ministry. “The skyway is the people’s turf,” says the 32-year-old Hamilton, founder of the Church Metro of Twin Cities. Two years ago, he had never set foot in the greater metropolitan area of Minneapolis—Saint Paul. “The minute I stepped into a skyway that first day, I knew God wanted me here.” He adds, “the skyway brings people together in a unique way. It’s ideal for reaching professionals downtown with the gospel.”

A Boardroom Ambiance

Church Metro is unusual for more than its location. Its leaders wear the stylish apparel of executives and managers rather than the white collars or vestments of the clergy. Its offices on the fifth floor of a recently constructed glass tower reflect boardroom ambiance, not stained-glass sanctity.

As the visionary force behind Church Metro, Hamilton first decided to bring God’s love to the skyways and conference rooms of Minneapolis and St. Paul’s marketplaces while still pastoring a church in Menomonie, Wisconsin. “The call I received from God in 1987 was completely unexpected. It made no logical sense. I didn’t have the financial backing of my church, certainly no profit incentive, only the conviction that there was a need.”

After much prayer, Hamilton began to drive 150 miles every other week and set up ten-minute appointments with executives. The meetings quickly convinced him that the needs were real and confirmed his sense of God’s call. Hamilton resigned his pastorate and, with his wife, Judy, and their two-year-old son, moved to Minneapolis.

With no nucleus of people, no organization to support him officially, Hamilton worked 15-hour days conveying his vision. “Although a person may wear a very nice suit, inside he or she may be crippled, blind, or impoverished,” Hamilton remembers stressing to people. “My objective was to bring the concept of Christ as Redeemer to everyone from CEOs to receptionists, to fill an appetite—a spiritual appetite—for which Jesus Christ is the answer. That was my motivation.”

Certified financial planner Greg Molle is among the dozens of volunteers Hamilton has attracted to help reach the executives and office workers. “Traditionally the poor, the homeless, and the inner city have been the mission field of the church,” he explains, “but corporate America—the crossroads where our country does business—has been largely ignored.”

Hamilton began holding monthly (now, twice-monthly) noon-hour services in the auditorium of a national insurance corporation served by the skyway. The seats are padded, the stage has a wide, leisurely look, the floor is carpeted, and the podium up front gives no clues that it will soon double as a pulpit.

Services begin like clockwork at 12:10 (allowing workers time to walk the skyway to the auditorium). Live music—designed to settle and quiet people after an intense morning of work—prepares the hundred or so worshipers for Hamilton’s message.

Hamilton keeps his messages to the point, limiting himself to seven to eight minutes. He applies Scripture to business situations whenever he can: setting personal goals, persevering through stressful times, enhancing careers.

“We strive to show from Scripture how Christ is involved in all the intimate details of life,” Hamilton explains. Thinking of some in his audience who face being laid off because of a corporate takeover, for example, Hamilton presses a point about God’s care. “Is God in this or not?” he asks. “If he is, then claim it. Let him be your helper.” The service is brought to a businesslike close after a half-hour; Hamilton knows how important schedules are to managers and office workers.

“My focus remains at the top of the ladder,” says Hamilton. “I knew that if I could inspire executives first, and get them to own the vision, then the remaining levels of management would follow.” So far, a core of 10 to 12 executives have stuck out the early months. “Because of their vocal support, and the popularity of the skyways with salaried and hourly workers, about 250 lay people have joined as Church Metro regulars,” he says.

Regular attender Steve Stormoen, a bank staff consultant, explains, “It’s a place to do business with God.” Stormoen came to appreciate the sessions so much that he now regularly invites unbelieving associates to services. “I’d been at the bank 20 years but couldn’t share my faith until now.”

Diedre Dahlstrom, a manager at Dayton Hudson headquarters, has had similar experiences. “I might say to a young woman coworker, ‘Here’s what I’m doing for lunch; want to come along?’ A couple of my friends have really opened up and have been spiritually enriched.”

The 30-some worship services held to date, which began with 20 in attendance, now average over a hundred. “Eventually, we hope to offer three to five brief worship meetings daily—a frequency that will increase people’s freedom to come and go,” Hamilton adds.

The Heart And Soul Of Business

Church Metro also provides counseling by phone, appointment, or in person. Eleven coordinators at nine different corporations (such as Dayton Hudson, Pillsbury, and Norwest Bank) help Hamilton keep track of people’s needs. Coordinators also sometimes counsel. They look for ways to help hurting coworkers, model Christian living, and be professional and spiritual mentors. “We act as a sounding board for coworkers and listen objectively. We want to help people deal with family pressures, marriage, or divorce,” Hamilton says.

By mid-1991, Church Metro even expects to have a ministry center situated on the skyway that offers walk-in counseling, and a video center showing spiritually oriented programs. To finance the facility, Hamilton and his board of directors (which includes two women) are raising money by word of mouth. They are quietly asking local churches to include them in their mission budgets and are “stirring up awareness” at meetings among individuals.

While a media center may seem impersonal to some, Hamilton thinks it provides a way to help while at the same time it respects an individual’s rights. Aware of the retail atmosphere of the skyway, he wants his approach to be like that of the stores around him. “We’re not into buttonhole evangelism. Any retailer today knows a customer wants ‘space’ until he or she needs help; then a friendly salesperson will step in. We want to respond rather than confront, to let our guests be guests and take the initiative.”

Hamilton reaches for the Bible in his briefcase. “Of course, we intend to provide the truth,” he concludes. “If a person applies what he or she has learned and sees how it works, we hope it will dawn on him or her, ‘Hey, I’m putting into practice a biblical principle. This works.’ In turn, we believe they will consider Christ as their Lord and Savior.”

By John Prin, a video producer and free-lance writer living in Minneapolis, Minnesota.