Ten years after Seventh-day Adventists defrocked one of their leading evangelicals, they are still debating their true identity.

Ten years ago, evangelicals watched with concern as the Seventh-day Adventist Church defrocked one of its noted scholar-preachers, Desmond Ford. While church officials claimed Ford’s teaching undermined their fundamental doctrines, other observers believed he was merely trying to bring Adventist teaching into line with the Bible and the Reformation.

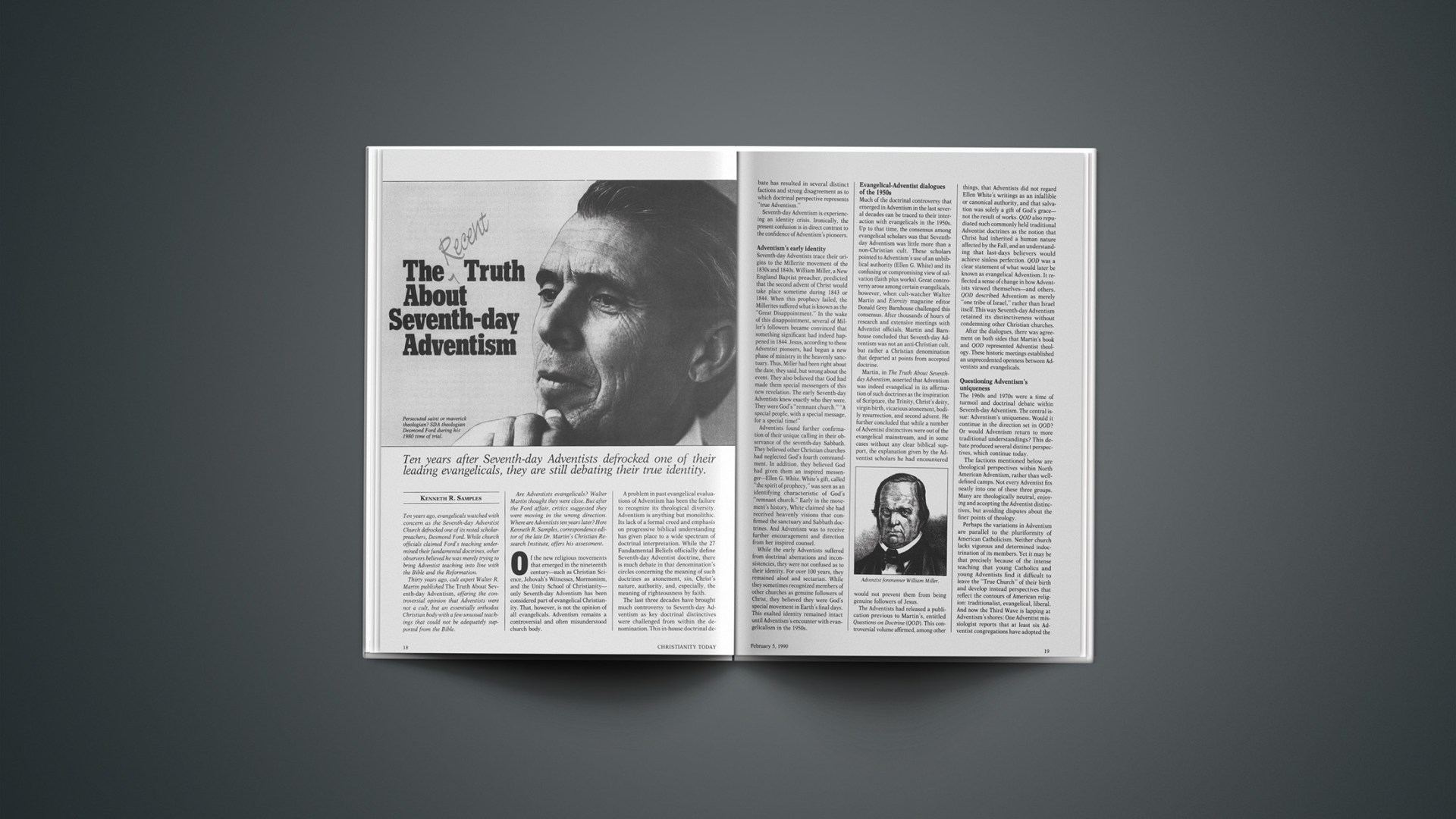

Thirty years ago, cult expert Walter R. Martin published The Truth About Seventh-day Adventism, offering the controversial opinion that Adventists were not a cult, but an essentially orthodox Christian body with a few unusual teachings that could not be adequately supported from the Bible.

Are Adventists evangelicals? Walter Martin thought they were close. But after the Ford affair, critics suggested they were moving in the wrong direction. Where are Adventists ten years later? Here Kenneth R. Samples, correspondence editor of the late Dr. Martin’s Christian Research Institute, offers his assessment.

Of the new religious movements that emerged in the nineteenth century—such as Christian Science, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mormonism, and the Unity School of Christianity—only Seventh-day Adventism has been considered part of evangelical Christianity. That, however, is not the opinion of all evangelicals. Adventism remains a controversial and often misunderstood church body.

A problem in past evangelical evaluations of Adventism has been the failure to recognize its theological diversity. Adventism is anything but monolithic. Its lack of a formal creed and emphasis on progressive biblical understanding has given place to a wide spectrum of doctrinal interpretation. While the 27 Fundamental Beliefs officially define Seventh-day Adventist doctrine, there is much debate in that denomination’s circles concerning the meaning of such doctrines as atonement, sin, Christ’s nature, authority, and, especially, the meaning of righteousness by faith.

The last three decades have brought much controversy to Seventh-day Adventism as key doctrinal distinctives were challenged from within the denomination. This in-house doctrinal debate has resulted in several distinct factions and strong disagreement as to which doctrinal perspective represents “true Adventism.”

Seventh-day Adventism is experiencing an identity crisis. Ironically, the present confusion is in direct contrast to the confidence of Adventism’s pioneers.

Adventism’S Early Identity

Seventh-day Adventists trace their origins to the Millerite movement of the 1830s and 1840s. William Miller, a New England Baptist preacher, predicted that the second advent of Christ would take place sometime during 1843 or 1844. When this prophecy failed, the Millerites suffered what is known as the “Great Disappointment.” In the wake of this disappointment, several of Miller’s followers became convinced that something significant had indeed happened in 1844. Jesus, according to these Adventist pioneers, had begun a new phase of ministry in the heavenly sanctuary. Thus, Miller had been right about the date, they said, but wrong about the event. They also believed that God had made them special messengers of this new revelation. The early Seventh-day Adventists knew exactly who they were. They were God’s “remnant church.” “A special people, with a special message, for a special time!”

Adventists found further confirmation of their unique calling in their observance of the seventh-day Sabbath. They believed other Christian churches had neglected God’s fourth commandment. In addition, they believed God had given them an inspired messenger—Ellen G. White. White’s gift, called “the spirit of prophecy,” was seen as an identifying characteristic of God’s “remnant church.” Early in the movement’s history, White claimed she had received heavenly visions that confirmed the sanctuary and Sabbath doctrines. And Adventism was to receive further encouragement and direction from her inspired counsel.

While the early Adventists suffered from doctrinal aberrations and inconsistencies, they were not confused as to their identity. For over 100 years, they remained aloof and sectarian. While they sometimes recognized members of other churches as genuine followers of Christ, they believed they were God’s special movement in Earth’s final days. This exalted identity remained intact until Adventism’s encounter with evangelicalism in the 1950s.

Evangelical-Adventist Dialogues Of The 1950S

Much of the doctrinal controversy that emerged in Adventism in the last several decades can be traced to their interaction with evangelicals in the 1950s. Up to that time, the consensus among evangelical scholars was that Seventh-day Adventism was little more than a non-Christian cult. These scholars pointed to Adventism’s use of an unbiblical authority (Ellen G. White) and its confusing or compromising view of salvation (faith plus works). Great controversy arose among certain evangelicals, however, when cult-watcher Walter Martin and Eternity magazine editor Donald Grey Barnhouse challenged this consensus. After thousands of hours of research and extensive meetings with Adventist officials, Martin and Barnhouse concluded that Seventh-day Adventism was not an anti-Christian cult, but rather a Christian denomination that departed at points from accepted doctrine.

Martin, in The Truth About Seventh-day Adventism, asserted that Adventism was indeed evangelical in its affirmation of such doctrines as the inspiration of Scripture, the Trinity, Christ’s deity, virgin birth, vicarious atonement, bodily resurrection, and second advent. He further concluded that while a number of Adventist distinctives were out of the evangelical mainstream, and in some cases without any clear biblical support, the explanation given by the Adventist scholars he had encountered would not prevent them from being genuine followers of Jesus.

The Adventists had released a publication previous to Martin’s, entitled Questions on Doctrine (QOD). This controversial volume affirmed, among other things, that Adventists did not regard Ellen White’s writings as an infallible or canonical authority, and that salvation was solely a gift of God’s grace—not the result of works. QOD also repudiated such commonly held traditional Adventist doctrines as the notion that Christ had inherited a human nature affected by the Fall, and an understanding that last-days believers would achieve sinless perfection. QOD was a clear statement of what would later be known as evangelical Adventism. It reflected a sense of change in how Adventists viewed themselves—and others. QOD described Adventism as merely “one tribe of Israel,” rather than Israel itself. This way Seventh-day Adventism retained its distinctiveness without condemning other Christian churches.

After the dialogues, there was agreement on both sides that Martin’s book and QOD represented Adventist theology. These historic meetings established an unprecedented openness between Adventists and evangelicals.

Questioning Adventism’S Uniqueness

The 1960s and 1970s were a time of turmoil and doctrinal debate within Seventh-day Adventism. The central issue: Adventism’s uniqueness. Would it continue in the direction set in QOD? Or would Adventism return to more traditional understandings? This debate produced several distinct perspectives, which continue today.

The factions mentioned below are theological perspectives within North American Adventism, rather than well-defined camps. Not every Adventist fits neatly into one of these three groups. Many are theologically neutral, enjoying and accepting the Adventist distinctives, but avoiding disputes about the finer points of theology.

Perhaps the variations in Adventism are parallel to the pluriformity of American Catholicism. Neither church lacks vigorous and determined indoctrination of its members. Yet it may be that precisely because of the intense teaching that young Catholics and young Adventists find it difficult to leave the “True Church” of their birth and develop instead perspectives that reflect the contours of American religion: traditionalist, evangelical, liberal. And now the Third Wave is lapping at Adventism’s shores: One Adventist missiologist reports that at least six Adventist congregations have adopted the worship style and kingdom theology of John Wimber’s Vineyard Fellowship. This is remarkable in a church that has steadfastly resisted the charismatic renewal, but it shows the adaptability of Adventism.

What follows is a helpful picture of broad currents within Adventism.

Evangelical Adventism: Evangelical Adventism can be traced to the Adventist scholars who dialogued with Martin and Barnhouse, and who produced the volume QOD. That book had clearly asserted that while Ellen G. White possessed a gift of prophecy, neither she nor her writings were infallible and should not be used as doctrinal authority. In addition, QOD had repudiated the long-standing Adventist belief that Jesus Christ had taken a sinful human nature at his incarnation. The positions taken on these two doctrines were a bold step.

This movement continued to evolve throughout the 1970s, with two of the strongest advocates being Australian scholars Robert Brinsmead and Desmond Ford, major catalysts of a revival of the doctrine of justification by faith. The problems of understanding the distinctions between justification and sanctification had plagued Adventism throughout its history. Evangelical Adventists were united in their understanding of righteousness by faith: It was justification only; sanctification was but the accompanying fruit. In their understanding, justification was distinct from, and logically prior to, sanctification. Nevertheless, the two were not to be separated. Evangelical Adventists thus affirmed the Pauline and Reformational understanding of righteousness by faith. Some of the main representatives of this group were R. A. Anderson, H. M. S. Richards, Sr., Edward Heppenstall, Robert Brinsmead, Desmond Ford, Smuts van Rooyen, and Hans LaRondelle.

Traditional Adventism: QOD also fueled the fires of those who supported Traditional Adventism. Following its publication, M. L. Andreasen, a highly respected Adventist theologian, severely criticized the volume, stating that it had sold Adventism down the river. QOD’s evangelical emphasis had robbed Adventism of some of its distinctiveness. Andreasen was particularly concerned about how the sanctuary doctrine and the human nature of Christ were explained. During the 1960s and 1970s, a number of other prominent scholars believed that QOD had not reflected the beliefs and identity of Seventh-day Adventism accurately enough.

Traditional Adventism rests squarely upon the authority of Ellen G. White. Traditionalists strongly defend distinctive Adventist beliefs, especially those that received their stamp of approval from Mrs. White’s prophetic gift. Some among Traditional Adventists emphasize her writings to the degree that they become the infallible interpreter of Scripture, using them as a shortcut to biblical understanding. Many of these Traditional Adventists were, however, deeply disturbed by charges of plagiarism when it was discovered that significant sections of Mrs. White’s writings relied rather too heavily on other Christian writers.

A Sanctuary Movement

The “sanctuary doctrine” is an important part of the Seventh-day Adventist story, although few contemporary Adventists can explain it and few Adventist theologians still teach it. In a nutshell, it says that Jesus is now acting as High Priest in fulfillment of the Old Testament Day of Atonement, just as 2,000 years ago he acted as Sacrificial Lamb in fulfillment of the Passover.

As our High Priest, according to traditional Adventist teaching, Jesus is doing two things. First, he is examining the heavenly records, determining who will be saved and who will be lost: those whose sins are forgiven are saved; those with unforgiven sins are not. This aspect of his work, in Adventist terminology, is called the “Investigative Judgment.”

Second, Jesus is actually disposing of the sins of the saved. In Old Testament times, sins were forgiven twice daily, but they were carried out of the camp only once a year. Similarly, some Adventists believe, Jesus forgives sins as soon as we confess them, but he disposes of them only during the last days.

Early Adventists, it should be emphasized, did not make all this up. They believed in an inerrant Scripture, which could be understood by comparing one text with another—although that appeared sometimes to be irrespective of context and primary meaning. The doctrine produces some controversial theological by-products.

One of those by-products was the notion that although God had forgiven the sins his people had confessed through the centuries, he had not really forgotten them. They had been stored up to be used later against anyone who might backslide. Another by-product was the teaching that between the time Jesus would expunge the record of a believer’s sins and the time he would return to earth, that believer would be without a Mediator. Consequently, Adventists were taught they would need to achieve a sinless state before the Second Coming. A third by-product was the idea that Satan (as the typological scapegoat) would in the last analysis bear the punishment for sins confessed by Christians. (While evangelicals might agree that Satan bears some responsibility for sin, they asked their Adventist brethren what price Jesus himself had paid on the Cross, if indeed Satan would ultimately bear the guilt?)

Although the Adventist leaders of the 1950s assured Walter Martin and Donald Grey Barnhouse that they rejected any of the questionable implications of this teaching about the heavenly sanctuary, some traditionalist Adventists have revived these and other harmful by-products of the 1844 theology. No wonder evangelicals continue to be confused about Adventism.

By David Neff.

Traditional Adventism also has a distinct view concerning righteousness by faith. This view is in direct contrast to the view held by Reformation-oriented Adventists. A vocal and perfectionistic segment within Traditional Adventism has classified Evangelical Adventism as a “new theology,” which destroys Adventism’s true identity.

Liberal Adventism: The theological perspective represented by Liberal Adventism does not arise out of the same doctrinal controversies as the previous two perspectives. In part, Liberal Adventism comes out of that church’s attempt to achieve theological and cultural respectability. In the 1950s and 1960s, many Adventist students began receiving graduate degrees from non-Adventist universities. In many cases, the schools attended by these Adventists were theologically liberal. Thus, Adventist scholars were influenced by modern biblical criticism and liberal theology.

Liberal Adventists minimize the concept of forensic justification, the legal metaphor of God acting as a judge who acquits us of our sins because of the doing and dying of Christ. In addition, the typical Liberal Adventist avoids describing the Atonement as Jesus’ suffering the wrath of God against sin as our substitute. In essence, Liberal Adventism denies the view of the Atonement at the heart of the Reformation.

Unlike other types of Adventism, Liberal Adventism is comfortable with diversity of practice and pluralism of thought. While it emphasizes Adventism’s distinctiveness (Sabbath, health), it sometimes seems to ignore historic Christian orthodoxy. Liberal Adventism is not concerned at all with maintaining a “remnant” identity like that of the nineteenth-century pioneers.

Which Is The True Adventism?

The 1980s have been a time of real crisis within Seventh-day Adventism as several representatives of Evangelical Adventism were fired or forced to resign because of their uncompromising views. The controversy peaked in 1980 when Desmond Ford, an outspoken advocate of Evangelical Adventism, challenged the biblical validity of the sanctuary doctrine, the one doctrine that supported Adventism’s remnant identity. Ford argued that that doctrine had no biblical warrant, and was only accepted because of Ellen G. White.

Ford believed that Adventism’s identity should not be tied to a doctrine that was indefensible from Scripture, but in its acceptance of the eternal gospel, justification by faith. Adventism, according to Ford, had been raised up by God to emphasize, along with justification by faith, such doctrines as sabbatarianism, creationism, conditional immortality, and premillennialism. Many Adventist administrators and leaders disagreed with Ford. As a result, his teaching and ministerial credentials were removed. Ford’s dismissal angered many within the Evangelical Adventist camp. In North America and Australia, Adventism lost a significant number of members—although just how many left is difficult to determine.

Evaluating Seventh-Day Adventism Today

In the late 1970s, Seventh-day Adventism was at the crossroads: Would it become thoroughly evangelical? Or would it return to sectarian traditionalism? Denominational discipline in the 1980s against certain evangelical advocates gave a strong indication that there is a powerful traditionalist segment that desires to retain Adventism’s 1844 “remnant” identity. As well, the liberal perspective, with its emphasis on pluralism, appeals to many Adventists. While Evangelical Adventism has lost ground in the 1980s, its supporters remain, though they are not nearly as prominent today.

Like any Christian group, if Seventh-day Adventism is going to be blessed of the Lord, its identity must come from a fidelity to the everlasting gospel. May the leaders and scholars within Seventh-day Adventism have the courage to return to the good news preached by the apostles and the Reformers. May it not be said that Seventh-day Adventism is more sure of its denominational distinctives than it is of the gospel.

Whatever Happened to Desmond Ford?

Ten years ago, Desmond Ford, a prominent and outspoken Seventh-day Adventist theologian, was defrocked by his denomination for challenging the traditional understanding of some of Adventism’s most distinctive doctrines. This strong disciplinary action sent shock waves throughout the Adventist denomination, and a significant number of Evangelical Adventists left in favor of independent Adventist and mainline evangelical churches.

Ford, who spent nearly 20 years as a professor of theology at Seventh-day Adventist colleges in Australia and California, was well equipped to establish his ministry independent of denominational auspices. He possesses two earned doctorates—one of them in New Testament studies from the University of Manchester under F. F. Bruce. And he has written some 18 books on such varied topics as the Sabbath, eschatology, apologetics, and preventive medicine.

Following his dismissal in 1980, Ford founded Good News Unlimited (GNU) of Auburn, California, a nondenominational Christian organization that sponsors lectures and seminars throughout North America, Europe, Australia, and parts of Asia.

While Ford continues to embrace a number of distinctive Adventist doctrines (e.g., sabbatarianism, conditional immortality), his ministry today is primarily to a non-Adventist audience. His gospel-centered preaching and strong emphasis upon health as a means of stewardship make him popular among many evangelicals. Asked recently about his denominational leanings, he responded, “While I am sympathetic to much of Adventist theology, I belong to the invisible church of Jesus Christ.”

By Kenneth R. Samples.