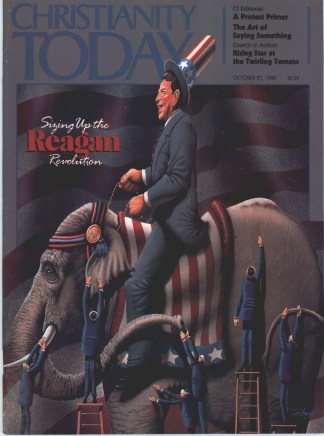

Bully For The Bully Pulpit

Ronald Reagan’s advent overlapped with the rise of the “Religious Right,” which helped elect him. Thereby hangs a tale.

One of the remarkable facts of our time is that religious communities are deeply riven, not exactly over politics, but in a way that politics expresses vividly. During the sixties and seventies, the activity of the “Religious Left” (it is curious that this phrase is rarely used) was taken for granted. Clergymen and laymen of all faiths campaigned for a variety of “progressive” causes, summed up in the slogan “peace and social justice.” Some denominations even reformed themselves internally, as by ordaining women and avowed homosexuals, in keeping with the secular agenda of the Left.

But the rise of the Religious Right in 1980 came as a shock. Liberal pundits who had seen nothing amiss in the activism of the Religious Left contended flatly that this new activism on the Right was an unconstitutional violation of the separation of church and state. If a bishop denounced the Vietnam War, he was acting properly, even “prophetically”; if he denounced abortion on demand, he was “interfering” in secular affairs.

The political division within the churches seems to stem from a prior theological division.

Those who believe dogmatically—in the literal truth of revelation, in the efficacy of sacraments, in the active providence of God in daily events—tend to be politically conservative. Those who espouse liberal theologies tend to favor more permissive personal morality and more socialist-style government.

For many years, the dogmatic believers stayed aloof from politics, at least qua believers, out of a general feeling that the sacred and the secular were so remote from each other that the one had no particular “relevance,” to use the cant word, to the other. Meanwhile, the Religious Left was insisting on relevance. It transferred its concern from the afterlife, in which its faith was weak, to the political arena, where salvation was to be achieved. Utopia replaced heaven, and South Africa replaced hell.

Dogmatic believers have never accepted the salvific view of politics, which is why they were slow to get into the game. But the horrors of the modern state, ranging from abortion on demand to religious persecution, finally taught them the negative relevance of politics to religion. By 1980, this realization crystallized in the Religious Right and other forms of counteractivism.

The dogmatists (I don’t intend the word pejoratively, since I count myself among them) threw their lot in with Ronald Reagan, who in return has supported them and their causes far more than any other President. He opposed legal abortion, favored school prayer, advocated tax relief for private schools, put religious persecution on the human rights agenda, and welcomed a variety of religious leaders, from Jerry Falwell to Mother Teresa.

It may be objected that most of this is only symbolic. I agree, except that I wouldn’t belittle that symbolism. Reagan has used the bully pulpit of the presidency to reinforce the legitimacy of political participation by religious people. As a result, even their enemies no longer deny their right to play the game.

As the years go by, I think we will come to appreciate more fully what Reagan has done to enhance the status of religion in America and its civic life.

By Joseph Sobran, a syndicated national columnist and an editor of National Review magazine.

The Dangers Of Idol Gazing

The Reagan years have certainly bolstered a kind of religious rhetoric in our public life. The President and many of his colleagues have felt comfortable exhorting some (but by no means all) religious groups, and in turn those groups have responded with their own exhortations to the rest of us. Yet, one wonders whether we ought to confuse religious rhetoric (as given us by certain ministers and a particular President) with the spirit of Christianity (as it was evoked for us 2,000 years ago, and as it has been handed down for us through various institutions over the generations).

Here is what a woman (a wife, a mother, a person who works for a computer company) told me a year or so ago: “I think this President has gotten along just fine with our ministers, but I’m not even sure if he ever goes to church himself, and I’m not sure if he pays much attention to what our Lord said when he came here to be with us, and what he did when he lived here among us.

“I think it’s great that lots of our ministers love him, and if they feel glad he’s in the White House, that’s great, too. But to me, he’d be a great President if he got more and more of us to live like Christ did—among the poor, and the people who were suffering and unpopular. That’s the way religion and politics should meet—not a lot of talk, and White House visits, but a politician trying to follow in the steps of Jesus, living his way.

“And I don’t see the Reagans pushing us in that direction. They’ve welcomed the Christianity of certain important ministers and the Christianity of certain moral positions, and I’m glad for it, because I’d like to think I’m a Christian. But, you see, we should be careful about calling ourselves Christians, and saying someone is pro-Christian. You can begin to sound as full of yourself as can be.… You can lose sight of how Jesus lived, and you can try to have it both ways—Christian talk, and a life full of ‘idol gazing.’ ”

I asked her what she meant by “idol gazing.” So she patiently explained to me:

“I mean by that all the fads and tin gods we worship when we’re not worshiping God. I don’t think Reagan has helped us forget all the ‘idols’ and keep Jesus in the front of our thinking. Reagan has been a great friend of some of our outspoken Christian folks, and he’s said what a lot of Christians think on some questions; but has he inspired us to follow the lead of Jesus in our lives—the way we live them? I’m not convinced [he has].”

I share her doubts. I fear we have heard much religiously suggestive rhetoric—a nice feeling, given some of the agnostic, secular idolatries we have to endure constantly—but if the test of a particular presidency is the degree to which it has inspired in a people a Christian devotion that is lived (the works of mercy and charity the humble Jesus offered his fellow human beings), then I must share my informant friend’s caution, if not outright skepticism.

By Robert Coles, professor of psychiatry and medical humanities at Harvard Medical School and the author of The Political Life of Children (Atlantic Monthly, 1986).

The Public Square Is Still Naked

The eight years of the Reagan presidency have seen a number of significant developments on the religion-and-society front in these United States: the full-blown emergence of evangelical Protestants from the cultural wilderness; the new visibility of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops on a host of public-policy questions; the churnings within American Judaism on the question of the “naked public square”; and the continued erosion of mainline Protestantism as a culture-forming force in American public life.

Yet these changes were well under way prior to the 1980 election, and while the Reagan presidency may have given each of these geological shifts a particular piquancy, it simply can’t be maintained that the fact of a Reagan administration was the key variable in effecting the changes in question.

Nor can it be said that the administration has done much to clarify some of the most bitterly controverted issues on the religion-and-society agenda. The jurisprudence of the federal judiciary still seems to reflect Prof. Laurence Tribe’s famous (or infamous) definition of the “free exercise” clause of the First Amendment: an “accommodation” of religious “interests” under the overarching constitutional imperative of “no establishment.” Perhaps this bizarre mindset will change over time, given Reagan administration appointments to the federal bench. But the administration itself has played a decidedly minor role in reshaping the public discourse on the imperative transition from “naked public square” to the “civil public square.”

Nor has the administration made much of a substantive contribution to creating a wiser public moral discourse on such first-principle questions as war and peace, abortion, reproductive technology, and euthanasia. Some modest and laudable initiatives at the policy level have been undertaken, ranging from the creation of the National Endowment for Democracy to revised Health and Human Services regulations on the care of handicapped newborns. But the public arena remains pretty much as before: deeply divided, awash in public moral emoting, but having very little evidence of genuinely public moral argument at hand.

It could, and should, be added that it is not primarily the responsibility of the federal government to chart the passage from naked public square to civil public square: from Alasdair MacIntyre’s “civil war by other means” to John Courtney Murray’s “creeds intelligibly in conflict.” That is a task for the institutions of our culture, and preeminently our religious institutions. But the administration could have exercised some leadership here by way of intellectual and rhetorical example. (And by “example,” I do not mean appearances by the President at the National Religious Broadcasters’ convention.)

Put it this way: The Reagan administration has not done a lot of damage to the argument over the relationship between religious conviction and American public life, and it has made some difference for the good. During the Reagan presidency, millions of American believers thought of themselves as something other than the quirky sectarians that the new class-dominated high culture continued to insist they were. But the naked public square remains to be clothed, and opportunities for advancing that urgent task have been missed.

As, I might add, I fully expect they will be under President Bush or President Dukakis. It is going to take some time, apparently, for our political leaders to catch up with the fact that modernization does not necessarily mean secularization in America.

By George Weigel, president of the James Madison Foundation and the author of Catholicism and the Renewal of American Democracy (Paulist Press, forthcoming).

Adapting To The Age Of Greed

The Reagan Revolution in religion leaves America feeling different, talking different, and acting pretty much as it did before.

As someone who opposed many of Reagan’s policies, and who found him to be personally “sincere but inauthentic” in matters of religion, I have to say that not much of what his administration did impinged on or altered “my” world.

For example, his support of a school prayer amendment was probably genuine and certainly inexpensive. He constantly talked about the need for prayer in schools, but never lifted a finger or risked a vote on an important issue to promote the cause. Reagan made few “born again” appointments, and most of those he did embarrassed the born again. He believes in, and gives encouragement for, development of a “Christian America,” (code named “Judeo-Christian”), but unless his judicial appointments effect changes over the long term, we are no closer to such a legal privileging of a tradition than we were in 1980.

Of course, the American climate is different than it was in 1980. The leaders of once-excluded groups, fundamentalists and Pentecostals and sometimes evangelicals (though Billy Graham blazed their trail 40 years ago), now have access to the White House and places of power as never before. But one must question whether they changed America as much as America changed them. Once somewhat ascetic, partly otherworldly, and disciplined, their best-known leaders now come across as adapted to the Age of Greed, worldly in their endorsements and hedonistic ways (restrained by a few bounds, like those of marriage in the case of sexuality), and triumphalist. America is better at letting people “in” than leaving them “out” to sulk or engage in prophetic protest.

The Reagan Revolution was, then, more talk (or all talk) and represented little actual reorientation of national life. It was important (very important) for the ways it gave Americans means to express their hungers—for restored family life, neighborhood values, patriotism, affirmation of marriage, antipermissiveness, antirelativism—but, eight years later, we do not see concrete expressions to match the desires and claims.

Religion is more respectable than it was 20 years ago, more exploited by politicians, more ready to brag about its place under the republic’s sun. In all this something haunts, something one recalls from Montesquieu, who so influenced the nation’s founders two centuries ago: The way “to attack a religion is by favor, by the commodities of life, by the hope of wealth; not by what drives away, but by what makes one forget; not by what brings indignation, but by what makes men lukewarm, when other passions act on our souls, and those which religion inspires are silent.” The general rule “with regard to change in religion, invitations are stronger than penalties.”

And so it has been. Which leaves room as an agenda item for the 1990s the retrieval of some more sober, self-disciplined, exacting themes about which the older evangelicalisms knew better than did most of their heirs in our decade.

By Martin E. Marty, Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago, senior editor of The Christian Century, and author of Religion and Republic: The American Circumstance (Beacon, 1987).

The Cultural War Will Continue

My evaluation is premised on the proposition that politics is, in largest part, a function of culture, and at the heart of culture is religion. Politics is largely controlled by the available ideas in a society (culture), and the most powerful ideas are religious in character, if not in name. To be sure, each of these three factors significantly affects the others. The Reagan years changed the ways these forces relate to one another, and the change will last into the foreseeable future.

The Reagan political triumph was produced by a religio-cultural shift, and it also accelerated that shift. The shift was occasioned by resentment and alarm generated by what I have called the naked public square. Critically important developments were related to public disputes over school prayer and abortion. Decisions on these and other questions were perceived to be aimed at excluding religiously grounded morality from American public life. An elite paradigm of secularization ran into the reality of an incorrigibly religious society. The reassertion of that reality created the Reagan years, and was also strengthened by them.

The reassertion preceded the Reagan years and was crucial to the election of Jimmy Carter. But President Carter was soon perceived to have betrayed the promise of a greater role for popular morality, including religious morality. Whatever his personal beliefs or behavior, Ronald Reagan skillfully exploited a cultural insurgency motored by the social forces of religion.

The insurgency was notably expressed in the emergence of the “Religious Right” and the new public assertiveness of Roman Catholic leadership. These two groups had and have important agenda differences but are united in their attachment to cultural conservatism and their insistence upon the role of religion in helping to order our public life. The political triumph of the insurgency with Ronald Reagan gave many previously timorous Americans “permission” to go public with the moral claims they had earlier confined to the realm of the personal and private.

The insurgency continues, and is mightily aided by the collapsing self-confidence of secular, usually liberal, forces. That collapse is due to policy failures, but, more important, to the growing implausibility of its philosophical premises. To be sure, the proponents of the secular paradigm are entrenched in some of the most powerful and prestigious institutions of the society. They are entrenched and besieged.

I am like many, perhaps most, Americans in wanting to be religiously faithful, culturally conservative, politically liberal, and economically pragmatic. By 1972 the dominant forces in the Democratic party had redefined “politically liberal” in a manner hostile to cultural conservatism and indifferent to religion. Democrats do not win in national politics, because they have invited the perception that they are contemptuous of democratic morality—which in America is pervasively, if confusedly, religious. That is why the next President will likely be a Republican.

More important than the political outcome, however, is the phenomenon of which politics is a part. The phenomenon is the continuing Kulturkampf, a war over the definition of American culture—over the ideas by which we should order our life together.

By Richard John Neuhaus, director of the Rockford Institute Center on Religion and Society and author of The Naked Public Square (Eerdmans, 1984).

Ronald Reagan’S Albatross

More than 20 years before the rise of the Religious Right, a group of Christian soldiers established a model for achieving social change. Even if not the perfect model, it created an ideal of fairness, equality, and inclusiveness. This standard, which challenged both Republican and Democratic Presidents, dramatically conflicts with the narrow agenda of today’s political Christians, who wrap themselves so tightly around Ronald Reagan that it is difficult to know where their spirituality begins and their politics ends.

Contrasting the movement led by Martin Luther King, Jr., and that led by the Religious Right shows how far downhill we have come—from religious leaders transforming society to those attempting to co-opt the White House for their selfish ends. As a consequence, right-wing political Christians have become their own worst enemies. Thus their domestic platform, symbolized by a forced return of prayer to the nation’s schools, goes unfulfilled. If the Religious Right had borrowed a couple of verses from the black ministers—led civil rights movement, maybe their road would have been easier.

King’s civil rights movement was nonviolent, based on love. But where is the love among the Religious Right? Where is the compassion to carry out the basic Christian acts of feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, and loving our neighbors?

As many see it, the Religious Right touted a godless message—trumpeting war in Central America and cooperation with South Africa. What is Christian about fueling a Nicaraguan war that is claiming thousands of innocent lives and maiming thousands of others? Where is the sense of outrage as blood flows freely among the innocents of South Africa? If the Christian standard is “Thou shalt not kill,” why is it not applied evenly? Why is the sight of a dead black South African not as chilling as that of a dead contra?

With its heavy-handedness and intolerance, the Religious Right has left a bitter. For example, the Right’s concern for family could have won converts had it not seemed a scheme to cram narrow values down people’s throats. Sadly, the Religious Right fought civil rights issues that would work to provide economic support for families of the poor. And their silence on family issues as they affected the poor and minorities was deafening. No outrage could be found for families without homes, and those forced to pile up in tragic, dope-riddled heartbreak hotels.

Thus the legacy of Ronald Reagan and his albatross, the Religious Right, is bitterness, opening new wounds with minorities and the poor. If nothing else, the Reagan legacy teaches us how divided we can become when religious groups give politics a higher priority than the simple Christian ethics of loving our neighbors—including the brown, poor, and black ones—as ourselves.

By Barbara Reynolds, USA Today Inquiry page editor and the author of And Still We Rise: Interviews With Fifty Black Role Models (USA Today Books).