For most, the sermon is the only pastoral care they’ll get.

The importance ascribed to preaching rises and falls in the ongoing life of the church. We may now be living in a time of homiletical recession, marked by a lack of strong and visible models, and, for some clergy, by a preference for pastoral care over preaching. This is perhaps the result of demands made by what the sociologist authors of Habits of the Heart have identified as the prevailing “therapeutic culture” of contemporary American society.

Any clergy who are tempted to embrace the therapeutic preference, and any parishioners who willingly accede to it, would do well to remember an exchange between two laypersons reported in a recent volume on preaching. Said one, “Our minister’s sermons aren’t very good, but I forgive him that because, during a recent crisis in our family, he was immensely attentive and helpful.” Said the other, “I’m afraid I can’t overlook his homiletical shortcomings. My family and I have not needed his help in a crisis, and those sermons are the only pastoral care we get.”

The most direct classical warrant for Christian preaching was issued by the apostle Paul in his Epistle to the Romans: “… everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord shall be saved. But how are they to call upon him in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in him of whom they have not heard? And how are they to hear without a preacher?… So faith comes by hearing, and what is heard comes by the preaching of Christ” (10:13–14; 17).

Faith comes by hearing: That assertion marks a profound insight linking anthropology, history, theology, and ministry.

The Centrality Of Language

Take anthropology, the study of human culture. It is our complex capacity for the word that makes each of us human and marks us off from the dumb world around us. George Steiner has put the point with near-poetic force, in writing that language is “the defining mystery of man.… [I]n it his identity and historical presence are uniquely explicit. It is language that severs man from the signal codes, from the inarticulacies, from the silences that inhabit the greater part of being.”

What makes a human self unique among all of the forms of being is its capacity for a certain kind of transcendence—what Reinhold Niebuhr understood that ancient word spirit to mean. My selfhood subsists in my capacity to view my own existence as it were from the outside. To be a self is to be aware of my self being a self and to be aware of my awareness of being a self.

How do I achieve this quality of spirit? Only by occupying the vantage point of other selves, by understanding their attitude about me. And that attitude is expressed in sounds, signs, and gestures. I understand what the other’s attitude is only when I know what those things mean. Language is the system of symbolic communication, made up of sounds, signs, and gestures by which I am able to identify and enter into the experience of another.

When I internalize the experiences and meanings of another self, I not only learn something about the other; I also learn something about myself. When I am permitted to participate in the feelings, perceptions, and commitments of another person, the result is that I begin to identify, to clarify, to sort out my own feelings, perceptions, and commitments, whether for acceptance or rejection.

So, we are human because of a capacity for the word shaped by the gift of language. Man/woman is the being who is capable of being addressed, the animal who answers.

Sociologists Brigitte and Peter Berger call language “the fundamental institution of society,” partly because it is the first institution encountered by every human individual. We might think, say the Bergers, that we first encounter the family. But it is language—sounds, signs, gestures—that initially impinge upon consciousness, and only later does a child become aware of the social reality known as “the family.” Language is the fundamental social institution, not only because it is the first we meet, the Bergers tell us, but because it is the primary instrument of socialization and hence the institution upon which all other human institutions rest.

The Power Of Rhetoric

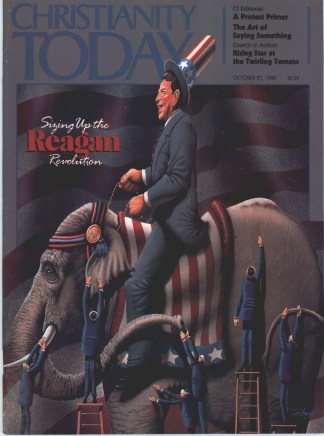

So much for anthropology. Now let’s look at history. We have had a relatively recent lesson, and a politically stunning one, in the power of language to shape perception, experience, and behavior. The election of Ronald Reagan to a second presidential term was, I am persuaded, almost entirely a rhetorical tour de force. Evidence for that judgment is found in the fact that many were moved to vote for him who disagreed with his specific policy positions, and that many—especially blacks and the poor—voted for him against their own self-interest.

Why was Ronald Reagan the “Teflon” President, to whom charges of misinformation and disinformation simply would not stick? It was because his rhetoric created a vision of the American character and experience with which many among us identify and would like to believe, and the rhetorical force of his telling has made it believable. It is a vision of America and Americans that is confident, endlessly optimistic, well-intentioned, prideful, militant and machismic, sentimental and anecdotal; a vision that appropriates—with its own distinctive interpretations and for its own ideological purposes—the “traditional” American values of love for country, family, and God.

Ronald Reagan announced that, in his second term, he intended to lead a “second American revolution.” However subsequent events have aborted that hope, Reagan was right in understanding the connection between rhetoric and revolution. Every genuine revolution is, in its very essence, a rhetorical tour de force. Every revolution requires—every revolutionary teaches—a new language. Revolution is never simply a matter of seizing the centers of physical power. That is unlikely to be possible in the first instance, or if possible, is unlikely to be sustained for very long unless there is some empowering vision, some new way of saying what our world is and who we are that is so compelling it moves men and women to risk and revolt.

Sigmund Freud created an intellectual and behavioral revolution when he gave us new names for the psychodynamic forces we had experienced but for which we had no adequate language. “Ego,” “id,” “superego,” “repression,” “sublimation,” “unconscious,” “infantile,” “Oedipal”: the seeds of revolution—of radically new perceptions, remedies, and permissions—were in those words.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels created an intellectual and political revolution when they gave new names to the structural and historical forces that had victimized masses of the world’s population; and naming those forces brought new power over them. “Dialectical materialism,” “ideology,” “proletariat” and “bourgeoisie,” “class struggle” and “classless society”: these were the really potent weapons, with bombs and machine guns only a subordinate level of armament.

History warns us against believing that there is any such thing as “mere rhetoric.” Ronald Reagan demonstrated again, if demonstration were needed, that rhetoric itself is a form of action—perhaps the most potent form. Because of the importance of language to our basic constitution as persons, there is for us no such thing as “innocent” language. All utterance matters and has consequences.

We are living in a period of history when there is insufficient understanding of the direct linkage between the quality of language and the condition of personhood, with the result that language carelessly used, or deliberately distorted, has humanly demeaning consequences.

When a billboard tells us that “Love is a loan from Fidelity Savings Bank,” that cheapening of language about love cheapens the experience of love and makes it more problematic. When airline policy requires bored attendants to tell us what a “pleasure” it has been serving us, that trivialization of language about pleasure trivializes the experience itself and makes it more problematic.

When the ordinary meanings of language disintegrate, the human society shaped by that language is imperiled. Said literary critic Kenneth Burke, “[I]n a bad time … one ought to have the decency to compose good sentences.” Indeed, in a bad time, the composing of good sentences is among the most direct, essential, and humane forms of historical action.

Faith By Hearing

Come now from anthropology and history to theology. Nothing I have said will surprise those who locate themselves within the biblical tradition. The importance of the word—so important, indeed, that it epitomizes the divine action—the formative and transformative power of the word, the critical importance of maintaining the integrity of the words we use: all that was in the biblical record long before anthropologists and historians came upon it.

Faith does come by hearing. The littleness or the largeness of our world view is given to us in the gift of language. No one can see in the world what his language will not permit him to say, as the philosopher Wittgenstein insisted. The ways in which we perceive reality, and our own places within reality, are formed by language. So the problem of being human is, in the most profound sense, a verbal problem: the problem of finding the language, or the languages, that will permit us to get into right relationship—effective, productive, creative, sustaining relationship—with the world within us and around us.

In order to live effectively, I need the words ordinary language gives me—words that convey a vast amount of information about myself and my world, that can put me reliably in touch with the phenomena of my daily existence. But more than information, I need meaning: a way of describing life so that it makes sense, a way of ordering and organizing the welter of impressions so that I can see life steadily and see it whole.

All of which is to say that, beyond the ordinary language that gives me location within what is seen, I need another language that links me to the unseen: faith language. Faith supplies the all-encompassing vision. It transcends each particular and draws all particulars together into a manageable, because meaningful, whole; it helps me to distinguish appearance from reality; and it centers and steadies my life journey. No merely descriptive language can bring about such a transformation; only faith language, invested with meaning and purpose, is powerful enough to evoke it.

Where am I to learn such a language? As with ordinary speech, I must receive it as a gift from those who already know it. To have faith is to receive a word spoken to my condition—a word that touches me where I hurt; that draws me to a recognition of myself and my world as they are, rather than as I might prefer to think they are; that reorders my life because it gives me a new point of reference; that gives me the energy that comes with new insight.

In the Christian tradition, Jesus Christ comes to me as the Word that is spoken to my condition. “Faith comes by hearing, and what is heard comes by the preaching of Christ.”

When, as sometimes happens, we find faith hard to come by, or when we feel it slipping away, we may wonder why. One reason may be that we have attempted to substitute sight for hearing. That often happens to educated women and men especially. We ask to be shown, we want to be convinced by objective evidence. And when the evidence is objectively unconvincing, we say, “I just don’t see it!” But faith comes not when we are shown but when we are addressed. It comes not as a demonstration but as a demand.

Another reason for the elusiveness of faith may be that we have moved out of hearing distance. Faith can come only to those who are within hearing distance, which is to say, within the community where faith language is spoken, and who there dare to confess their need, to which the word of faith is heard as the answer.

The Good And Bad News For Ministry

What all of this comes to in the end, of course, is ministry, and there is some good news and some bad news in it. First the good news: Preaching matters fundamentally! Now the bad news: Preaching matters fundamentally!

The fundamental importance of preaching is good news to any preacher who has wondered whether or not it is worth the intellectual, spiritual, and rhetorical agony that must regularly be poured into it. It is bad news because the demand to speak a relevant word, week after week, to the real and compelling needs of a congregation is such desperately hard work from which many a preacher would gladly accept release. But it cannot be given in good conscience.

Furthermore, the fundamental importance of preaching is bad news because, as I have said, these do not appear to be great days for the American pulpit. Over the last two decades I have listened to sermons across the country, in small-town Kansas, Michigan, West Virginia, and Florida, in the metropolitan areas of Washington, D.C., Chicago, Kansas City, and Seattle—in many congregations in each place. And while I have heard, here and there, a remarkably good sermon, more often I have come away saying to myself, “What had all that to do with me?”

If there is a homiletical recession, we can identify some of the sources of it: the broad devaluation of language skills that sends even college graduates out lacking writing and speaking competence, and forces American business to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars annually teaching its managers to write a simple declarative sentence; the sin of graduate professional education, including the theological schools, in failing to take seriously enough the linguistic deficit students bring from the undergraduate experience; the conventional relegation of homiletics to second-class status in the seminaries; the widespread preference of the clergy for pastoral care, often at the expense of time for disciplined homiletical preparation; and increasing demands made on pastors for activity and visibility not only in the parish but in the community, further exhausting time for the reflection required for weekly utterance.

Whether we are preachers or lay auditors, we ought not to accept the diminution of human and gospel values that results from rhetorical inadequacy in the pulpit.

If it is true that language is “the defining mystery” of our humanhood, that the peculiarly human problem is a verbal problem, and that faith comes by hearing as the ordering and organizing word spoken to my condition, then there is no such thing as ineffective preaching. On those terms, all preaching has effect. The only question is what that effect will be, whether to strengthen and expand and confirm faith, or to diminish and limit it.

Whatever else resurgent fundamentalism may be, I believe it is at least partly a challenge to the mainstream American pulpit, which has failed to give men and women the clear and convincing faith-language they need to get on with their lives. Habits of the Heart, that important inquiry into the American character, has told us unequivocally that Americans today lack a language that is needed to make moral sense of their lives, with the result that there is an enormous amount of confusion both about personal relationships and social goods. We lack, say its authors, “a language to explain what seem to be the real commitments that define [our] lives, and to that extent the commitments themselves are precarious.”

The research of the Habits authors showed that the most widespread language used by Americans comes out of the “therapeutic culture.” It is the language they call “expressive individualism,” which urges each person to fashion his or her own private meaning and which, as a consequence, leaves that individual “suspended [in] terrifying isolation.” The message of these social-science researchers is that “it is a powerful cultural fiction that we not only can, but must, make up our deepest beliefs in the isolation of our private selves,” and that the crisis in the American character springs precisely from that fiction.

Renewing The Church

A great deal is being written and said these days about achieving a new vitality for the churches through the techniques of congregational growth and development, on the one hand, and the disciplines of spirituality, on the other. And there is no doubt that much good can come from improving organizational process and outreach, and from deeper habits of contemplation. One gets the impression, however—at least by omission—that it is possible to achieve these outward and inward dimensions of renewal without reference to the pulpit, casting the minister in the skilled role of corporate leader or of spiritual director, with scant attention to preaching.

I want to suggest another route to the outward and inward vivification of the churches, one that is rooted in a Renaissance-like and, as I believe, biblical awareness of the renewing potency of the word.

For the Renaissance man, words were units of energy. Through words man could assume forms and aspire to shapes and states otherwise beyond his reach. Words had this immense potency, this virtue, because they were derived from and were images of the Word, the Word of God that made us and that was God. Used properly, words could shape us in his image, and lead us to salvation. Through praise, in its largest sense, our words approach their source in the Word, and, therefore, we approach him.

If mainstream churches are to have anything to give to the unchurched, whom we seek to draw by the techniques of congregational development and outreach, or to have any effect on the superficial spirituality of many of the churched, there must be a renaissance of the pulpit—a recovery of what the first and sixteenth centuries knew, and of what fundamentalist evangelists to their credit seem not to have forgotten: that “faith comes by hearing, and what is heard comes by the preaching of Christ.”

Lloyd J. Averill, a faculty member at the University of Washington, is adjunct professor of theology and preaching in the Northwest Theological Union, Seattle.