UPDATE

Vietnam. In the United States, the word brings images of an unhealed wound. It inspires memories—most of them unpleasant—especially among those who fought there.

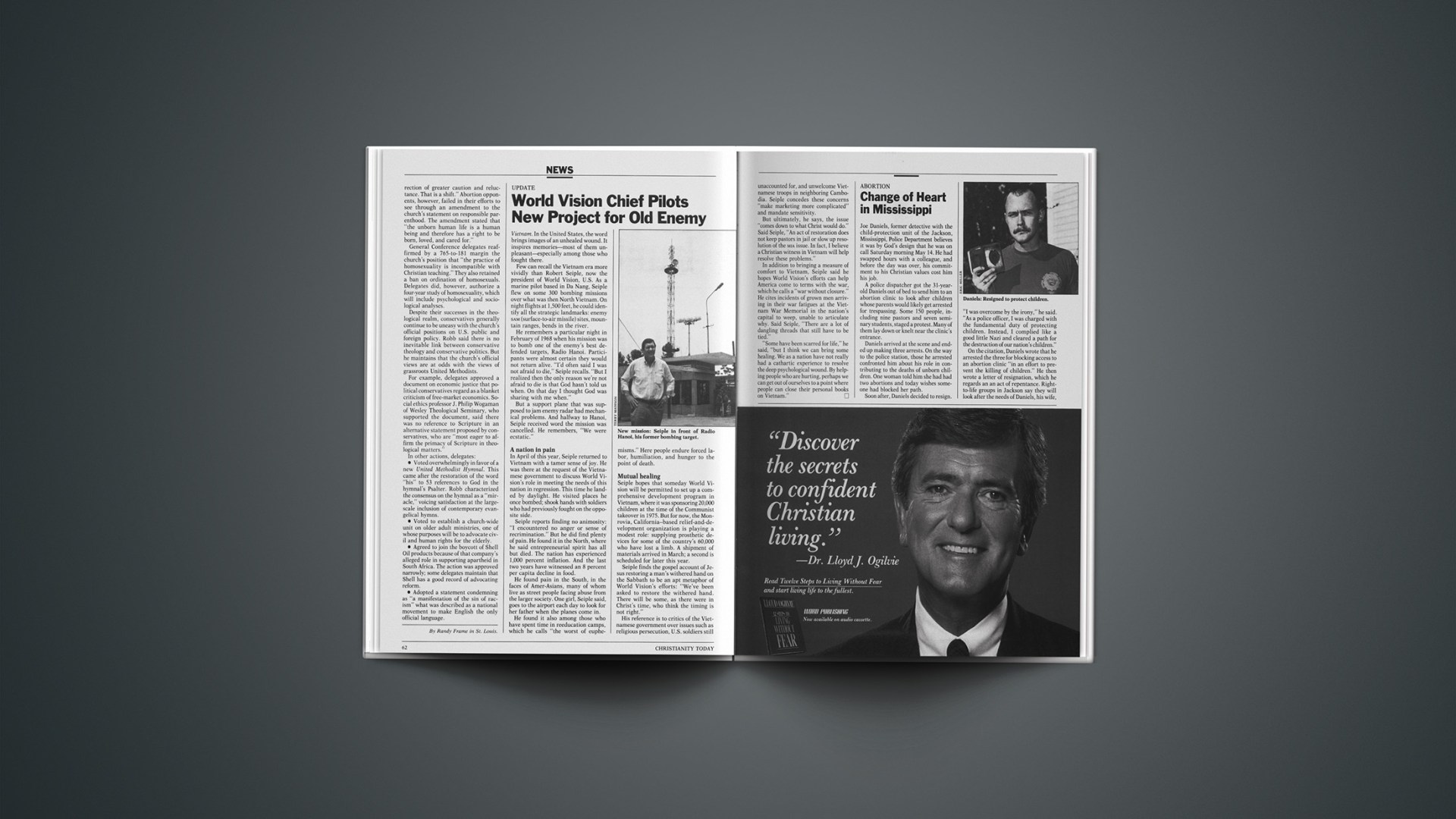

Few can recall the Vietnam era more vividly than Robert Seiple, now the president of World Vision, U.S. As a marine pilot based in Da Nang, Seiple flew on some 300 bombing missions over what was then North Vietnam. On night flights at 1,500 feet, he could identify all the strategic landmarks: enemy SAM (surface-to-air missile) sites, mountain ranges, bends in the river.

He remembers a particular night in February of 1968 when his mission was to bomb one of the enemy’s best defended targets, Radio Hanoi. Participants were almost certain they would not return alive. “I’d often said I was not afraid to die,” Seiple recalls. “But I realized then the only reason we’re not afraid to die is that God hasn’t told us when. On that day I thought God was sharing with me when.”

But a support plane that was supposed to jam enemy radar had mechanical problems. And halfway to Hanoi, Seiple received word the mission was cancelled. He remembers, “We were ecstatic.”

A Nation In Pain

In April of this year, Seiple returned to Vietnam with a tamer sense of joy. He was there at the request of the Vietnamese government to discuss World Vision’s role in meeting the needs of this nation in regression. This time he landed by daylight. He visited places he once bombed; shook hands with soldiers who had previously fought on the opposite side.

Seiple reports finding no animosity: “I encountered no anger or sense of recrimination.” But he did find plenty of pain. He found it in the North, where he said entrepreneurial spirit has all but died. The nation has experienced 1,000 percent inflation. And the last two years have witnessed an 8 percent per capita decline in food.

He found pain in the South, in the faces of Amer-Asians, many of whom live as street people facing abuse from the larger society. One girl, Seiple said, goes to the airport each day to look for her father when the planes come in.

He found it also among those who have spent time in reeducation camps, which he calls “the worst of euphemisms.” Here people endure forced labor, humiliation, and hunger to the point of death.

Mutual Healing

Seiple hopes that someday World Vision will be permitted to set up a comprehensive development program in Vietnam, where it was sponsoring 20,000 children at the time of the Communist takeover in 1975. But for now, the Monrovia, California-based relief-and-development organization is playing a modest role: supplying prosthetic devices for some of the country’s 60,000 who have lost a limb. A shipment of materials arrived in March; a second is scheduled for later this year.

Seiple finds the gospel account of Jesus restoring a man’s withered hand on the Sabbath to be an apt metaphor of World Vision’s efforts: “We’ve been asked to restore the withered hand. There will be some, as there were in Christ’s time, who think the timing is not right.”

His reference is to critics of the Vietnamese government over issues such as religious persecution, U.S. soldiers still unaccounted for, and unwelcome Vietnamese troops in neighboring Cambodia. Seiple concedes these concerns “make marketing more complicated” and mandate sensitivity.

But ultimately, he says, the issue “comes down to what Christ would do.” Said Seiple, “An act of restoration does not keep pastors in jail or slow up resolution of the MIA issue. In fact, I believe a Christian witness in Vietnam will help resolve these problems.”

In addition to bringing a measure of comfort to Vietnam, Seiple said he hopes World Vision’s efforts can help America come to terms with the war, which he calls a “war without closure.” He cites incidents of grown men arriving in their war fatigues at the Vietnam War Memorial in the nation’s capital to weep, unable to articulate why. Said Seiple, “There are a lot of dangling threads that still have to be tied.”

“Some have been scarred for life,” he said, “but I think we can bring some healing. We as a nation have not really had a cathartic experience to resolve the deep psychological wound. By helping people who are hurting, perhaps we can get out of ourselves to a point where people can close their personal books on Vietnam.”