What does it take to bring people together? For a community of 139 families in San Salvador, it took an earthquake. The “22nd of April” community (no one there knows how it got its name) was among the areas hardest hit by the October 1986 disaster that destroyed or damaged 52,000, or one-fourth, of San Salvador’s homes.

Immediately following the disaster, community residents took shelter in temporary shacks. But eventually all these people will move into new homes, thanks to a cooperative effort between Christians in San Salvador and World Relief, the relief-and-development arm of the National Association of Evangelicals.

After the quake, community residents petitioned the government for diesel fuel and a bulldozer so they could level the land on which their new community would be built. The area was divided into 139 plots and assigned to families randomly through a lottery.

“The earthquake was the catalyst that brought us together,” said Dimas Portillo, who was recently elected to another one-year term as president of the seven-member community directorate.

The project will result in a total of 1,200 homes for earthquake victims; more than 300 are already finished. World Relief generates the funds and purchases building materials, while Salvadorian Christians from three denominations and a large Baptist church provide the labor. The houses, built to be “earthquake proof,” cost about $700 each. The average income for a family of five or six in this region is $60 a month.

World Relief’s Peter Clark, who is coordinating the effort, says he is impressed by the industry of the Salvadorian people. “Some people spent their Christmas bonuses to fix up their houses. This is what happens when they have something they can call their own.”

Clark said an effort is made to identify locally produced materials and systems of construction so the houses become structures the people “can identify with sociologically.” This approach also spurs the local economy.

More Than Houses

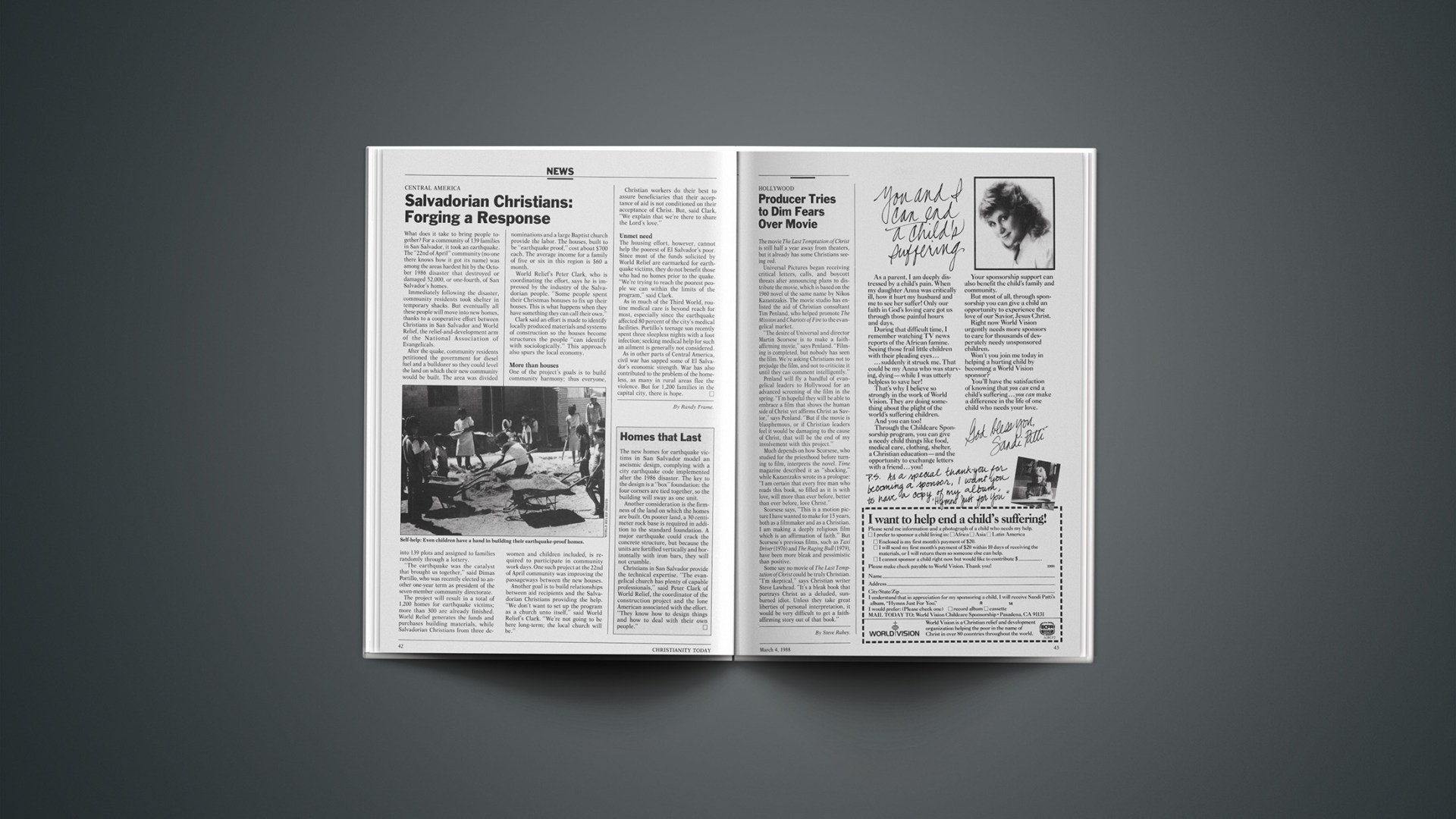

One of the project’s goals is to build community harmony; thus everyone, women and children included, is required to participate in community work days. One such project at the 22nd of April community was improving the passageways between the new houses.

Another goal is to build relationships between aid recipients and the Salvadorian Christians providing the help. “We don’t want to set up the program as a church unto itself,” said World Relief’s Clark. “We’re not going to be here long-term; the local church will be.”

Christian workers do their best to assure beneficiaries that their acceptance of aid is not conditioned on their acceptance of Christ. But, said Clark, “We explain that we’re there to share the Lord’s love.”

Unmet Need

The housing effort, however, cannot help the poorest of El Salvador’s poor. Since most of the funds solicited by World Relief are earmarked for earthquake victims, they do not benefit those who had no homes prior to the quake. “We’re trying to reach the poorest people we can within the limits of the program,” said Clark.

As in much of the Third World, routine medical care is beyond reach for most, especially since the earthquake affected 80 percent of the city’s medical facilities. Portillo’s teenage son recently spent three sleepless nights with a foot infection; seeking medical help for such an ailment is generally not considered.

As in other parts of Central America, civil war has sapped some of El Salvador’s economic strength. War has also contributed to the problem of the homeless, as many in rural areas flee the violence. But for 1,200 families in the capital city, there is hope.

By Randy Frame.

Homes That Last

The new homes for earthquake victims in San Salvador model an aseismic design, complying with a city earthquake code implemented after the 1986 disaster. The key to the design is a “box” foundation; the four corners are tied together, so the building will sway as one unit.

Another consideration is the firmness of the land on which the homes are built. On poorer land, a 30 centimeter rock base is required in addition to the standard foundation. A major earthquake could crack the concrete structure, but because the units are fortified vertically and horizontally with iron bars, they will not crumble.

Christians in San Salvador provide the technical expertise. “The evangelical church has plenty of capable professionals,” said Peter Clark of World Relief, the coordinator of the construction project and the lone American associated with the effort. “They know how to design things and how to deal with their own people.”