“The only music that hasn’t appeared at the church is my style—Bach,” laughs the pastor of Fleischmann Memorial Baptist Church in Philadelphia. In fact, the Juilliard-trained pianist who has been pastor of the inner-city church for 14 years, cheerfully admits that when the church’s black pianist plays “There Is a Fountain” and “Rock of Ages,” they do not sound at all “like when this white brother plays.”

James Correnti was a senior studying piano on scholarship at the well-known New York City music school during the sixties when he met God—and reordered his life. Though preparing for a career as a professional musician, he left music after completing his studies. “Music was my god,” he says. “I didn’t know how to worship only a little bit at the foot of an idol.”

Seeking a foundation for his newfound faith, Correnti pursued theological training at Reformed Episcopal Seminary in Philadelphia, graduating magna cum laude. To his surprise, he was shortly called as interim minister of the oldest North American Baptist congregation in the U.S., located in Philadelphia’s inner city. At the time, the church was about ready to expire. Today Fleischmann Memorial is experiencing steady growth, and Correnti long ago became its full-time senior pastor.

The church’s outreach into a multiethnic community heralded as the city’s cocaine capital—where as much as $150,000 worth of the drug has reportedly been sold daily—has attracted the attention of the news media: Fleischmann Memorial has been the focus of local TV coverage, and was described in the Reader’s Digest (Mar. 1987).

Situated in the midst of a community that is largely Puerto Rican and black, with lesser numbers of Filipinos, Southeast Asians, and a few whites, the church is now beginning to reflect the racial mix—an enormous change for what began 144 years ago as a German-speaking congregation. Outreach programs have included a thrift store, food bank, and highly regarded antidrug campaigns. It is, in Correnti’s words, a genuine spiritual counterculture in the midst of one of Philadelphia’s least desirable areas.

Once More With Meaning

In the midst of all this, Correnti got back his music.

James Correnti, concert pianist, appears regularly in concerts on the campuses of colleges, universities, seminaries, and Bible schools, and in churches. For 11 years he also taught on the summer faculty of the French School of Music in Plainfield, New Jersey.

On one particular day, the audience is rapt as Correnti sits at the keyboard, discussing a favorite composer, Johann Sebastian Bach. Drawing on his extensive study of the great German composer and his faith, the music that follows is infused with meaning. For the audience, “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” becomes more comprehensible: a German chorale familiar to Bach’s congregation, laced with the composer’s own, new melody as accompaniment. Then, because it is the Christmas season, Correnti discusses not merely the music, but the rich theology of a familiar Christmas hymn.

One couple, admittedly uninterested in music, later confess their difficulty in tearing themselves away to keep a dinner date.

Pianist In The Pulpit

Perhaps there are two James Correntis: the one, pastor of a church at the center of urban ministry; the other, the consummate musician.

When wearing his ministerial “hat,” Correnti does not stray from the pulpit to the keyboard. In fact, until a full-time assistant arrived to share the preaching, he never played the piano at Fleischmann Memorial services. Because the church was so inert when he arrived, he says, “I was the pastor, the preacher, the visitation committee, the evangelism committee—and, for the sake of the congregation, I would not be the pianist!”

When he reentered the arena of music performance, Correnti’s biggest problem was what to do with the kind of repertoire he had learned at Juilliard. Concerned about the spiritual insight of Christians into their music, he began by restructuring the way he performs. He looked for what was most accessible for his audience, particularly pieces under five minutes in length. And he studied how others—like Victor Borge and composer-conductor Leonard Bernstein—have made the music of the ages come alive for contemporary audiences. What evolved was a well-articulated and easily understood approach, which he has discovered makes his programs equally useful for evangelism.

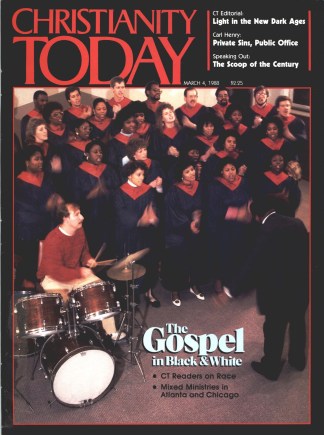

However reluctant to mix keyboard with pulpit, James Correnti, pastor, and James Correnti, musician, do coexist at Fleischmann Memorial. To try to understand his congregation better, he joined an all-black church choir—the “token white,” he laughs. “I think I really began to learn from the inside a little bit of what made them tick,” he says, “and how they enjoyed making music.”

There is now at the church what he describes as a well-worked mix. It includes the singing of psalms, historic hymns, Scripture songs, and gospel-era hymns, which, he says, in black hands have taken on a whole new life for him. He confesses to having had a “very heavy hand” in all of this in an effort to maintain balance; there is no one style that dominates. And although Bach is not part of the mix, Correnti has done some seminars to introduce that music.

In fact, what he now does in concerts in analyzing music—and hymn texts in particular—he developed first at the church. He saw a distinct need since many in the congregation struggle with reading skills; and because there is so much dense theology in a hymn like “A Mighty Fortress,” people simply do not understand what they are singing, he says. So he takes a stanza at a time and sets them up for it, explaining words they do not know, or changing them to contemporary language if necessary. The laboratory at Fleischmann Memorial has resulted in concerts and tape recordings that make great music understandable to his audiences.

James Correnti appears to have the best of two worlds: an effective ministry in one of the country’s neediest urban areas; and an effective music performance and teaching endeavor that makes the great music of the past come alive for Christian audiences. Not a bad way to live with a split personality.

By Carol R. Thiessen.