Aurora, Illinois (pop. 90,000), sits in the middle of small farms, 30 miles west of metropolitan Chicago. The amoebic spread of suburban Chicago has not yet engulfed its small-town distinctives, and all along Randall Road, the community’s northern approach, fields of corn and soybeans guard its rural virginity.

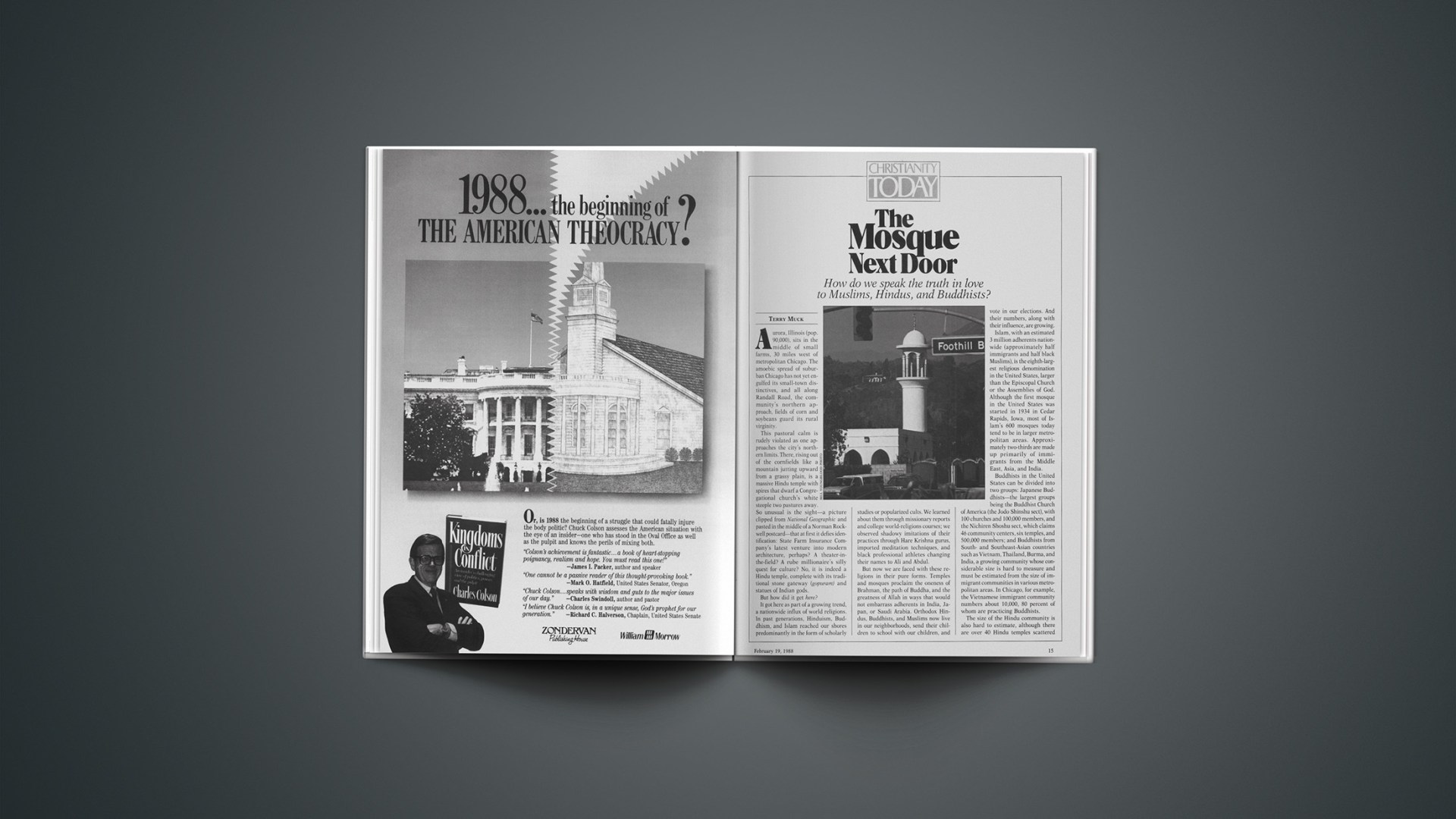

This pastoral calm is rudely violated as one approaches the city’s northern limits. There, rising out of the cornfields like a mountain jutting upward from a grassy plain, is a massive Hindu temple with spires that dwarf a Congregational church’s white steeple two pastures away.

So unusual is the sight—a picture clipped from National Geographic and pasted in the middle of a Norman Rockwell postcard—that at first it defies identification: State Farm Insurance Company’s latest venture into modern architecture, perhaps? A theater-in-the-field? A rube millionaire’s silly quest for culture? No, it is indeed a Hindu temple, complete with its traditional stone gateway (gopuram) and statues of Indian gods.

But how did it get here?

It got here as part of a growing trend, a nationwide influx of world religions. In past generations, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam reached our shores predominantly in the form of scholarly studies or popularized cults. We learned about them through missionary reports and college world-religions courses; we observed shadowy imitations of their practices through Hare Krishna gurus, imported meditation techniques, and black professional athletes changing their names to Ali and Abdul.

But now we are faced with these religions in their pure forms. Temples and mosques proclaim the oneness of Brahman, the path of Buddha, and the greatness of Allah in ways that would not embarrass adherents in India, Japan, or Saudi Arabia. Orthodox Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims now live in our neighborhoods, send their children to school with our children, and vote in our elections. And their numbers, along with their influence, are growing.

Islam, with an estimated 3 million adherents nationwide (approximately half immigrants and half black Muslims), is the eighth-largest religious denomination in the United States, larger than the Episcopal Church or the Assemblies of God. Although the first mosque in the United States was started in 1934 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, most of Islam’s 600 mosques today tend to be in larger metropolitan areas. Approximately two-thirds are made up primarily of immigrants from the Middle East, Asia, and India.

Buddhists in the United States can be divided into two groups: Japanese Buddhists—the largest groups being the Buddhist Church of America (the Jodo Shinshu sect), with 100 churches and 100,000 members, and the Nichiren Shoshu sect, which claims 46 community centers, six temples, and 500,000 members; and Buddhists from South and Southeast-Asian countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, Burma, and India, a growing community whose considerable size is hard to measure and must be estimated from the size of immigrant communities in various metropolitan areas. In Chicago, for example, the Vietnamese immigrant community numbers about 10,000, 80 percent of whom are practicing Buddhists.

The size of the Hindu community is also hard to estimate, although there are over 40 Hindu temples scattered throughout the country. Since the Indian population in most metropolitan areas is of significant size (100,000 in metro New York, for example), and since much Hindu worship takes place in the home, we can assume a large, uncounted number of practicing Hindus.

Together, these three faiths make up less than 4 percent of the total American population (85% Christian, 2% Jewish, 9% no faith). Yet combined, their nearly 800 places of worship make them a larger group than scores of familiar Christian denominations. Further, since the immigration laws favor professionally trained people (doctors, lawyers, and engineers), Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims have a relatively influential demographic profile. Separated from homeland and culture, they tend to cling to the faith of their roots with a high degree of commitment.

Hinduism: Clash Of World Views

Perhaps it is that sense of commitment more than anything else that concerns middle-American Christians. Consider the reaction of the Aurora community when they first heard in 1982 of the plans to build a Hindu temple on their city’s edge. The city council, which had to give approval for a building permit, was deluged with calls and letters from fearful citizens. At subsequent public meetings to debate the issue, the Hindus were accused of being rat worshipers, drug abusers, and part of an Indian government plot to buy up American land. Letters protesting the temple poured into the Aurora Beacon-News, outnumbering supporting letters by an estimated 20 to 1.

“Biblically oriented Christians in this community were naturally afraid of the propagation of a polytheistic faith in their community,” remembers John Riggs, pastor of the Union Congregational Church, close by the temple site. “I don’t think they were the ones making the irrational claims about rat worship and animal sacrifice. But they very definitely were concerned about the effect on their children and their children’s children.”

Riggs’s wife wrote a letter to the newspaper reminding citizens that violation of Deuteronomy 20’s prohibition of worshiping idols put the whole community in danger of God’s judgment. Riggs himself became vocal in the local ministerial association, and he regularly commented on the Hindu threat in a column he writes for a small-circulation neighborhood newspaper.

In the end, the city council approved the building plan—and Riggs was not shattered. “I thank God for the religious freedom we have in this country. I realize that if we were to deny that to this group, we would be putting our own freedoms in danger. But I wanted to make sure we demonstrated a strong Christian witness in this community, and point up the incompatibility of Hindu and Christian beliefs. Frankly, I’m concerned about the erosion of the basic Christian values that have shaped our society, and the competition the world religions present to those values.”

The wave of non-Christian immigrants claiming allegiance to one of the world religions does not upset us as much as the fact that we find ourselves so vulnerable to their potential for influencing—negatively, some say—our public way of life, which has heretofore been based on Christian values.

“The crucial religious issue is something quite different from the growing numbers of Hindus, Buddhists, and Muslims in this country,” says theologian Carl Henry. “At issue is the weakness of Western civilization in the face of competing world views. Modern naturalism nullifies the classic concept of one universal God over history. This trend toward scientism is hospitable to Asian religions that reject a Creator-creation distinction and encourage the theory that all religions are essentially one. In the world of tomorrow, Christianity will need to fend for itself either in a secularized social milieu of intellectual atheism that empties the churches, or in a society where a religious sense of many coexisting gods saturates civic culture.”

In short, the religions are coming, and our spiritual defenses are vulnerable. What is it we are to do?

Buddhism: Quietly Fitting In

The first time Jim Ziesemer, pastor of the Hope Evangelical Lutheran Church in West Chicago, Illinois, heard about Nichiren Daishonin Buddhism was when two women knocked on his parsonage door one Sunday afternoon and told him the Nichiren Shoshu Temple was to be built across the road from his church. “To say I was surprised would be an understatement,” says Jim. “We built our new church here in 1982 in an area full of Chicago commuters. Since then we have come to expect building announcements about new subdivisions, shopping centers, and high tech industrial parks. But a Buddhist temple caught us all by surprise.”

The temple is the regional headquarters of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism, a form of Buddhism that takes its name from a thirteenth-century Japanese Buddhist saint who claimed to bring knowledge that made the teachings of Gautama Buddha complete. Although the principle practices of these Buddhists take place in members’ homes through daily chanting of ritualized scriptures, regular services are held weekly at the temple. For certain holidays and special occasions, members come to the temple from a 17-state area, drawing from an estimated membership of 7,000.

According to Mr. Nakabayashi, head of the NSA Center (the church’s lay organization for recruiting members and coordinating lay support), his church has received a warm welcome not only from the community in West Chicago, but from people throughout the Midwest. As he told members at a recent worship service celebrating the death date of the sect’s founder, Nichiren Daishonin, “Who would have believed the tremendous growth we have experienced since building this temple here only six years ago?” The congregation of 400, made up of perhaps 20 percent Japanese immigrants, 50 percent black Americans, and 30 percent white Americans, responded with an enthusiastic ovation.

Not all American Buddhists have had the same kind of warm experience in their communities. Some discrimination exists. Isolated incidents of “religious persecution” do make headlines: Hindus in Aurora, Muslims in Michigan and Oklahoma, Buddhists in Washington, D.C. Yet the majority would claim that the United States Constitution’s freedom of religion clauses are not only preached, but practiced in grassroots America. “At first, when people at work find out you’re a Buddhist, they give you a funny look,” says Eric Carlson, an engineer in Des Plaines, Illinois. “But they get used to it. We have good discussions and they find out we’re after the same things: world peace, good relationships, happiness. We end up getting along just fine.”

Further, if Christians were presented with the two alternatives, toleration versus persecution, the vast majority would advocate toleration based on more than our country’s legal requirements. Most would point to the biblical admonition to “Love your neighbor as yourself” as one of the two great commandments of Christian behavior.

“I don’t recall any overly negative concern about the Buddhist temple,” said Pastor Ziesemer. “One woman from the neighborhood did call me and ask me what was being built across from our church. When I told her it was a Buddhist temple, she said, ‘A what?’ It took her a few minutes to regain her composure. But I would say that after the surprise wore off, our people simply accepted the temple as a fact. I think that if any of them meet temple members in their neighborhood, at school, or on the job, the reaction to them is simply one of being a good neighbor: helping and loving them as Christ commanded.”

Islam: Evangelistic Fire

Within a few blocks of the old gray stone building at 63 E. Adams Street in the heart of downtown Chicago, one finds the world-famous Chicago Art Institute, the massive Field Museum of Natural History, the Adler Planetarium, the Chicago Public Library Cultural Center, and the corporate headquarters of some of the nation’s most powerful businesses, including the Standard Oil Company, Borg Warner, First National Bank of Chicago, and the Quaker Oats Company. Yet, as you walk into the rooms on the third floor of this most typical of old Chicago-style business buildings, one hears neither esoteric museum discussions nor business talk.

What one does hear five times a day is the chanting of prayers to Allah. In a large oriental-carpeted room, men from the banks and businesses of downtown Chicago gather here at dawn, noon, afternoon, sundown, and evening to spend ten minutes reciting qur’anic prayers in unison. Since 1976 the Downtown Islamic Center has provided a religious refuge for the faithful, 90 percent of whom are immigrants from the Middle East who have come to the United States to pursue business opportunities.

The center also connects these believers with Muslims worldwide. A large map showing the distribution and concentration of Islam hangs on the wall (one in four people in the world is Muslim, a footnote proclaims). Books line the wall of the foyer: copies of the Holy Qur’an, The Glorious Qur’an, Islam and the Crisis of the Modern World, Islam: The Religion of the Future are just a few of the titles. The director, Yakub Patel, describes the activities of the center, and as he does so he communicates a forceful enthusiasm about his faith:

“Our purpose is to disseminate information about Islam. Over 200 people, professionals, clerks, students, come here for Friday prayers, which include a special Sabbath lecture in both English and Arabic. Twenty percent of those people are Afro-American, the rest immigrant Middle Easterners.

“There are many centers like this in the Chicago area. Over 6 million Muslims now live in the United States. We have much in common with the Christian and Jewish faiths. We believe in universal brotherhood of all men. We believe in very strict moral standards. Our creed is simple: There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his prophet. Anyone who can sincerely say that is a Muslim.”

Like everyone else in the center, Patel is a volunteer worker. His vocation is engineering, but he makes it clear that “the mosque is the center of my life,” and he spends many hours directing its mission, which in Christian terms could be called discipling of believers and evangelizing nonbelievers.

In those twin desires, Muslims are no different from members of other religious traditions. All claim truth. That is why there are religions: they give definitive answers to life’s most perplexing questions—Who am I? Why am I here? Where am I ultimately going? And because they give definitive answers, they demand choice. The Qur’an says, “There is no god but Allah and he alone is almighty. This is the right path.” The Bible says, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me.” Choose, brothers and sisters. As Richard Baxter said in The Reformed Pastor, “To be a Christian is not a matter of opinion.” Indeed. It is a matter of conscious choice.

So to represent the Christian faith well, we must tell the truth. We must proclaim the gospel in our sermons, recite the commandments about how to behave, and endorse the biblical revelation fully as the final answer. Nothing is gained by denying the unbreakable steel cable that connects truth and Christianity. To do so ultimately presents Christianity as something else—a nice philosophy or way of thinking rather then the steely faith of our fathers Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, David, Jesus, and Paul.

To put it more bluntly, if we do not teach the truth about Abraham and Jesus, Muslims will teach their truth about Abraham and Muhammad. They already do.

For the past two years, Muslims in the Chicago area have used a traditional Islamic celebration, Idd-Ud-Adha (an annual feast honoring the prophet Abraham’s extraordinary example of sacrifice and obedience to God), as an opportunity to explain their beliefs to non-Muslims. They have made it an evangelistic service. They invite over 200 business and social acquaintances to listen to readings from the Qur’an and ask questions of both immigrant and American-born Muslims. The explanations are, for the most part, even-handed and fair. Questions are sincere; answers are thoughtful. “Our purpose is for us to understand one another,” said Hasnain Ashrafi, one of the organizers of the event. “The difference between religions is of secondary importance—fear for the morality of our children in a secular, faithless world is our biggest concern, a concern we think we share with Christians.”

The moral strength of devout Muslims is legendary, witnessed, for example, by the program’s announcement of serving nonalcoholic drinks only. It is indeed something Christians can identify with. Yet, listening to the speeches about the greatness of Allah and the faithfulness of his Qur’an, one also cannot help detecting a further purpose in this evening’s happenings: to win converts to Islam. The table of free literature on Islam and free copies of pamphlets explaining its teaching is all too familiar to those who have grown up in churches with tract racks prominent in the foyer.

The presentation is not unpleasant. One soon learns that Christians are not the only ones adept at evangelizing. Zeal for one’s cause means telling others about it; convincing them means changing their minds about faith. The two go together. Yet it seems the whole world has discovered that the best way to do this is to be gentle as doves about it.

Christianity: Truth And Love

Is there anything at all distinctive about the Christian approach to evangelism, something that sets it apart from being one more item on a grocery list of religions? Yes, and it starts with the cushion of love that surrounds our truth. Richard Baxter warned that we not make our creeds, our claims to truth “any longer than God made them.” In so saying, Baxter was reflecting another astounding fact about the teachings of Jesus Christ. Just as Jesus turned the Torah teaching about loving one’s neighbor into an incredibly profound law of grace, he turned the teaching of truth into a graceful law. Without losing any of the value and importance of being right, he taught a way that moved from a warlike imposition of arbitrary values into a graceful experience of love in action.

Jesus did this in two ways. One was to remind us constantly of our human limitations. We are finite creatures, he taught, who cannot hope to understand things as fully as he did. He revealed this as much by the way he taught as anything. He unfolded truth slowly to his disciples, only as much as they were able to take at any one time. Some truths he couched in language that would only be understood by those who had “ears to hear.” Paul perhaps capsulized the reason for this best when he said poetically, “Now we only see in a glass darkly, soon we shall see face to face.” The lesson is clear: the truth is absolute and final, but our understanding of the truth will never be, this side of heaven.

Second, by frequently reminding us of our own sinfulness, Jesus (and Paul after him) taught us empathy for our neighbors. Theologian Kenneth Kantzer once said that “the level of one’s tolerance for those of other faiths is a true test of our understanding of the doctrine of original sin.” The only proper response to our own sin is humility, not only before God, but before our fellow men. Jesus modeled this. The Philippians 2 ode to his humility recalls that even “though he was God, [he] did not demand and cling to his rights as God, but laid aside his mighty power and glory, taking the disguise of a slave and becoming like men, and he humbled himself even further, going so far as actually to die a criminal’s death on a cross.” One of Jesus’ most unique and valuable contributions to religious behavior was his command to speak the truth in love.

The Bible teaches over and over again that we cannot shirk our duty to speak the truth. As G. K. Chesterton noted, “The man who is not ready to argue is ready to sneer.” There is no middle ground between speaking truth and remaining silent. One can, however, argue lovingly for the truth, and thereby become something special in today’s hard scrabble rush for religious market share.

Speaking The Truth In Love

It is emotionally satisfying to love one’s neighbor. It is intellectually stimulating to argue for the truth. The challenge of living the Christian life, however, is to be able to integrate the two.

In 1978 Ron Itano got down on his knees, prayed a prayer of repentance, and asked Jesus Christ to be lord of his life. “It was like the end of a long journey,” says Ron. “All the religious questions I had been asking all my life were answered in that one prayer.”

Religious questions came naturally to Ron, grandson of a Japanese Buddhist priest. Because the rest of his family still belongs to the Buddhist church, Ron sometimes wonders why he did not become Buddhist. Family, culture, and early childhood experiences all pushed him in that direction. “But my parents didn’t insist I become Buddhist. I remember going to services in my grandfather’s temple. But it didn’t appeal. I didn’t understand the service and no one bothered to explain it to me.” Fortunately, a Christian businessman decided it was worth explaining his faith to this young Japanese insurance underwriter.

“I met Paul Asp on the commuter train to downtown Chicago. Something attracted me to him. He always seemed so happy, so much on top of life. He was kind to me. Over the months we became friends. Then he told me about Christ.”

What Paul said made sense to Ron. He began to study the Bible and finally dedicated his life to Christ. “Paul’s friendship made a big difference,” says Ron. “I’ll always be thankful he took time to care and tell me about his faith.”

Two things happen when the light of the gospel strikes fire in a person’s soul. One is an incredible sense of trust in God where doubt and fear formerly existed. The other is a sudden recognition of truth that drives away the former darkness. The road to trust in God is paved with the smaller bricks of trust in men. The road to understanding is paved with clearly presented religious truths.

Two questions we all must ask ourselves about our Hindu, Buddhist, and Muslim neighbors: Are we doing our part to develop trust and love with them, trust that may lead to the more ultimate Trust? And are we articulate enough about our own search for faith, so we can convincingly, lovingly, present it to others?

Positive answers to those questions tell us that we are prepared to face the challenge of world religions, to aid a change of heart that leads to a change of mind.

Watertight Love

Does it make sense to apply a love ethic to the very people who live by philosophies we feel are threatening our way of life? Doesn’t that weaken our position?

This question is particularly crucial because it appears that our “competitors,” such as the Nichiren Shoshu Buddhists, are beating us to the punch in applying their own version of the law of love to the unchurched, underprivileged members of our society. One of the three pillars of Nichiren Buddhist faith is “practice for others,” which means aggressively telling others about the benefits of practicing Buddhism.

The Christian tradition demands the same kind of commitment. As a “law” applied by the Christian church over the last 20 centuries, love has borne remarkable spiritual fruit. One major reason the church of the first and second centuries grew was because its members gained a reputation for not only preaching this unusual ethic of love but actually putting it into practice.

Still, there are dangers. Christian love, if nothing else, is a risky proposition. Love makes one vulnerable—and perhaps there are some practical limits to that vulnerability. Perhaps love is sometimes so risky that temporary withdrawal from neighbors is called for. This is especially true for those who are not yet spiritually mature.

The spoken and unspoken concern in communities where foreign faiths are growing is the threat to the faith of children. “Soon after the Buddhist temple was built my daughter began kindergarten,” said Pastor Ziesemer. “The chief priest’s son was in her class. It wasn’t a problem for her—or us, I guess. The only time I can remember her mentioning it was when she said he brought the neatest show-and-tell things of anyone in the class. I feel good about her going to school with him. But I wouldn’t allow her to go to the temple to observe a worship service. Kids are so strongly attracted to the strange and different. Look at the girls trying to dress like Madonna, or boys trying to imitate punk rockers.”

In some situations, the concern can extend beyond the spiritually immature to include the institutional church, especially when it is operating in a hostile environment. Sometimes the social milieu is so dangerous, so secular, that not only are those weak in the faith endangered, but the church itself runs the risk of being identified with, or overrun by, the secular. It is in that context that Paul, in writing to the Corinthians, cautions them not to be yoked to unbelievers for fear the church would become identified with pagan practice.

Further, sometimes withdrawal is required to prepare for future engagement. Jesus spent much time with his disciples before embarking on a public ministry where he scandalously ate with publicans and sinners. Jesus’ entire ministry beat out a steady rhythm between active engagement of the forces of the world, strategic withdrawal to gain spiritual strength, and then active engagement again.

Interestingly, the Buddha also taught that teaching effectiveness should sometimes color the form and frequency that love for neighbor takes. He used the analogy of watertight and cracked water pots: If we have a choice of teaching the truth to those who will retain the truth and those who will not, we should start with those who will retain it, and only then go to those who will let much slip through the cracks.

Love is a powerful, many-faceted emotion; “Love your neighbor as yourself” is as true a command as exists in Scripture.

What does give us direction in applying the command to love our neighbor? Perhaps some understanding can be found in the very purpose of our love. Christian love is not to be undemanding, void of direction. As strongly as the Bible commands loving one’s neighbor as oneself, it also commands that we preach the gospel to all nations.

Thus, our love is to be pragmatic—not selfishly, but full of pragmatic concern about spreading the Good News. It must be consistent with our belief that without the gospel, all men and women will end up in eternal punishment. Can there be a more loving motivation than that to teach, as well as love?

By Terry Muck.