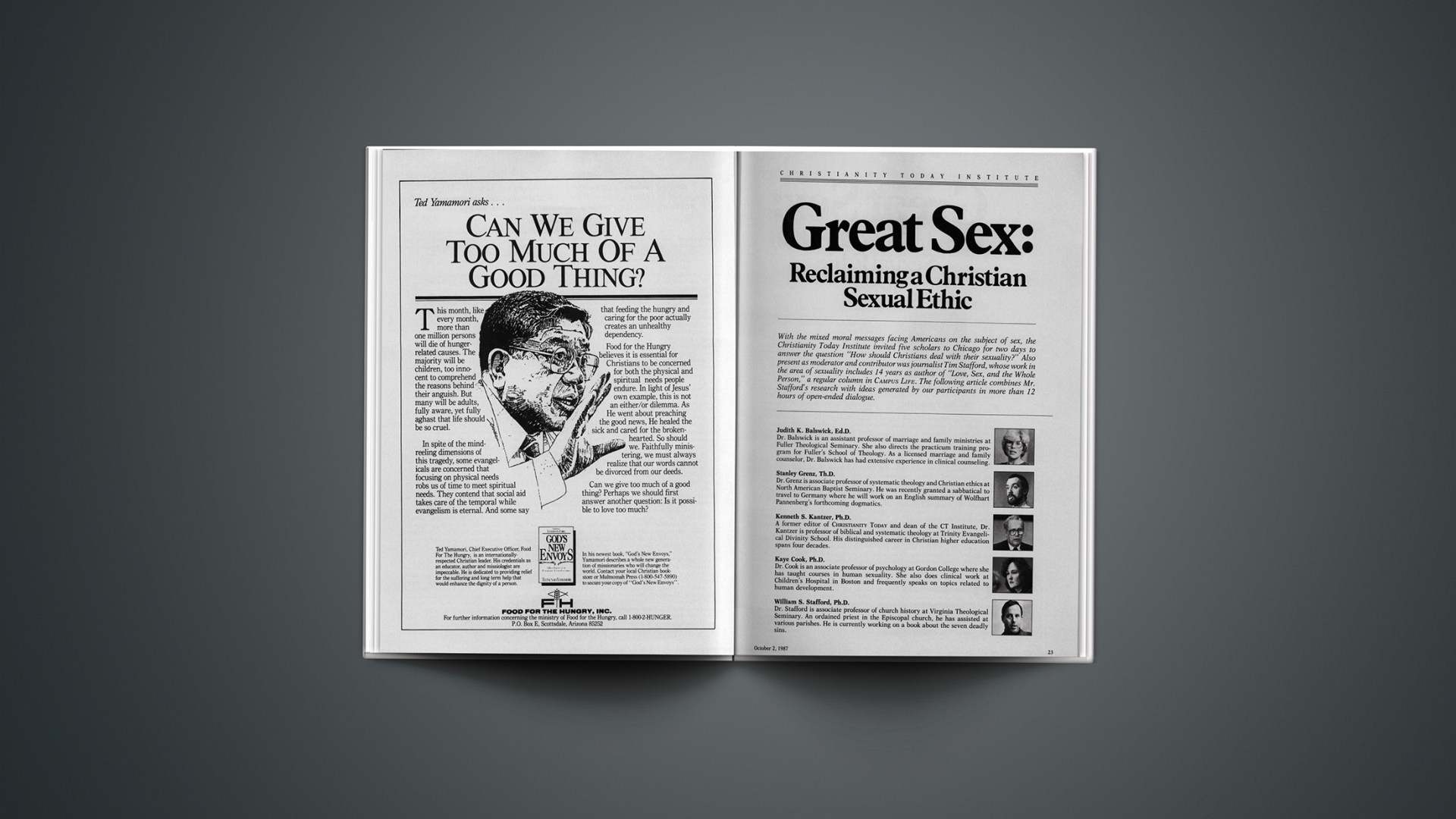

With the mixed moral messages facing Americans on the subject of sex, the Christianity Today Institute invited five scholars to Chicago for two days to answer the question “How should Christians deal with their sexuality?” Also present as moderator and contributor was journalist Tim Stafford, whose work in the area of sexuality includes 14 years as author of “Love, Sex, and the Whole Person,” a regular column in CAMPUS LIFE. The following article combines Mr. Stafford’s research with ideas generated by our participants in more than 12 hours of open-ended dialogue.

Judith K. Balswick, Ed.D.

Dr. Balswick is an assistant professor of marriage and family ministries at Fuller Theological Seminary. She also directs the practicum training program for Fuller’s School of Theology. As a licensed marriage and family counselor, Dr. Balswick has had extensive experience in clinical counseling.

Stanley Grenz, Th.D.

Dr. Grenz is associate professor of systematic theology and Christian ethics at North American Baptist Seminary. He was recently granted a sabbatical to travel to Germany where he will work on an English summary of Wolfhart Pannenberg’s forthcoming dogmatics.

Kenneth S. Kantzer, Ph.D.

A former editor of CHRISTIANITY TODAY and dean of the CT Institute, Dr. Kantzer is professor of biblical and systematic theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. His distinguished career in Christian higher education spans four decades.

Kaye Cook, Ph.D.

Dr. Cook is an associate professor of psychology at Gordon College where she has taught courses in human sexuality. She also does clinical work at Children’s Hospital in Boston and frequently speaks on topics related to human development.

William S. Stafford, Ph.D.

Dr. Stafford is associate professor of church history at Virginia Theological Seminary. An ordained priest in the Episcopal church, he has assisted at various parishes. He is currently working on a book about the seven deadly sins.

We Are Vulnerable

Martin Nestor knows perfectly well why he is excited about speaking at Sweetwater Christian Camp. The camp brochure lies innocently on Martin’s desk, and for the fifteenth time he lifts it and looks at her picture. Barbara Shinar, program director. Small as it is, the soft-focus, back-lighted photo catches the overspilling enthusiasm of Barbara’s eyes.

Both are happily married, with children they love. Infidelity would be horrific, going against everything they believe and teach. Yet every time they see each other, little darted looks fly. They will find some way to talk. Even in the camp dining room there will be an attentiveness between them, a softness of glance that can make him feel daring and courtly even handing her the salt.

Yet he assures himself that he is indulging a harmless infatuation. He understands the dynamics between men and women—he has even spoken on the topic—and he had never found them difficult to control. He truly, deeply loves his wife and family. Nothing will ever happen between him and Barbara.

Once we might have agreed with Martin, thinking that sexual impulses were not so difficult to channel. Good people stayed faithful; bad people did not. Today, however, Martin’s confidence seems naive, even foolish. Who really would have believed the news we have had to swallow in the last year? Who would have predicted the tales of sexual infidelity from Christian leaders? What could possibly have made them do it—to risk reputation, position, career, income, to say nothing of family and marriage?

And yet, such irrationality in pursuing sexual pleasure is not limited to leaders. When we hear that some friend or relative has deserted spouse and children, we are stunned less by the evil of the deed than by the implausibility. “What on earth could make her do it?” we want to know.

Considering the evidence, we would have to conclude that humans—even decent, God-fearing Christians—are vulnerable. The destructive specter of sexual sin is curiously inviting, and we are foolish to think we are immune. Jim Bakker, Gordon MacDonald, and that wonderful young mother in your church could all tell the same sad story: “I knew it was wrong. I never thought it would happen to me. It has destroyed something precious to me.” They understand how vulnerable we all are.

Not that vulnerability is all we can see in Martin’s situation. His impulses, while dangerous, retain much of the fundamental delight and goodness of sexuality. He sees Barbara’s beauty keenly, and this seems to make him more alert to all other kinds of beauty in the world around. He feels more alive. He is remarkably aware of his body, even his own breathing. He feels his own masculinity, and the charge that masculinity and femininity give to even the most insignificant interactions.

Sexuality is more than sex; it is the whole way we live in the world as male and female body-persons (to borrow Lewis Smedes’s word). Martin is more jubilantly aware of his sexuality than he has been in years. His vulnerability with Barbara does not appear to him wrapped in darkness, but rather clothed in light. Sexuality is a good gift, and never has it elated him more than now. Consequently, he is all the more vulnerable.

The form vulnerability takes varies; men may experience it as an irresistible drive, while women may feel it more often as a longing for love and intimacy. Either way, or in other ways, the danger is not simply “out there.” It comes from within. We do what we do not want to do, and the things we want to do, we are unable to do. We need a way to affirm and enjoy our sexuality without denying these dangers; and we need a way to guard against our vulnerability without denying our sexuality.

In a small way, that has already begun. Recently, Christians have given emphasis to the goodness of sex. We have rediscovered that God created all things good, including sexuality, and this has brought healing to many. Yet we need a fuller view. Sexuality, like everything else created, has fallen into trouble. We are more vulnerable than ever, living in a society that crowds sexual innuendoes into every available space, whether billboards or office conversations.

Looking For A Better Way

Societally we are reeling: burdened with an underclass of ruined families, staggered by millions of abortions, and terrified by sexual epidemics. The wide-eyed promises of the sexual revolution, that all would be well once Victorianism was uprooted, can hardly be made with a straight face any more.

Yet there has been no real popular surge to undo the sexual revolution, because few perceive themselves as being hurt. Plenty of people sleep together before marriage, even live together before marriage, and yet form strong relationships. Many homosexuals make outstanding, sober-minded citizens. Men and women leave their families to form new marriages, and seem to gain peace of mind.

After seeing a number of these cases, often in friends or family members, many Americans have lost any real ethical sense about sexuality, apart from a few vague ideals. They are not about to label anything “wrong,” however uneasy it makes them feel. “No-fault divorce” is not merely a legal innovation, it is a pervasive frame of mind.

Evangelical Christians, who have sometimes drawn the courage of their convictions partly from being the majority view, now find themselves representing a minority position on many matters, such as whether it is appropriate for two unmarried people who love each other to go to bed together. Christians are sounding an uncertain note on the ethics of sexuality. And the failure of Christians to facilitate practical sex education for their children is one sign of this. Mostly, it seems, we give lip service to our ideals, and keep a low profile.

This calls us to review our situation. Do we really mean what we say when we talk about fidelity? Do our ethics really help vulnerable people to experience their sexuality in the way God intended? Do our demands of self-sacrifice and self-control really have anything to offer a sexually vulnerable world?

Even if we have affirmative answers to these questions, our point of view is difficult to communicate. We hold very different presuppositions from our non-Christian neighbors. Consider the trends that have influenced society’s understanding of sexuality:

Secularism. Before the Enlightenment, Western people believed that God was intimately involved with every feature of life, public as well as private. That has entirely changed. Government, economics, science, education—from each one, God has been eliminated. Sexuality was perhaps the last realm. Garrison Keillor suggested humorously, on a “Prairie Home Companion” radio show, that at one time when the preacher said from the pulpit, “I’m only human,” everybody thought, “Who’s he committing adultery with?” “Sin” meant “sexual sin,” because it was practically the only sin left. People still felt guilty about what they did sexually, and they thought of God and heaven and hell in the immediate aftermath of their deeds.

But sex has, for most Americans, lost that sense of being right or wrong. It is simply a way for two people to be together. Sex can be analyzed and explained through laboratory experiments like those Masters and Johnson undertook. Previously, the idea of taking human beings into a laboratory, attaching devices to them, and then encouraging them to masturbate or copulate under the eyes of scientists would have seemed monstrously immoral. Today it is only distasteful. The very idea that there is an objective right and wrong about sexual conduct would strike many as absurd, like a claim that there is a right or a wrong way to paint a picture. Without God hanging over it, sexuality is left to the individual’s personal preferences.

Privatization. Before the Renaissance, houses did not ordinarily include corridors. Every room was a thoroughfare, so that no act save thought was truly private. Today, however, we consider many areas of life as strictly private. What a person does sexually is his business and his alone, unless he happens to be running for President. Thus a church that expels a member for sexual misconduct can be sued, and the majority of people seem to believe it should be, for they see sexual conduct as none of the church’s business.

The privatization of sex received a huge boost during the 1940s and 1950s, when penicillin and the Pill came out of the laboratories. Penicillin could cure syphilis, the AIDS of the generations before us, and the Pill made it possible to have intercourse without conceiving children. Both fostered what can now clearly be labeled an illusion: that sex, thanks to medical breakthroughs, had no impact on society. In an era of millions of abortions, of multiple generations of unwed mothers on public support, of epidemic sexually transmitted diseases, the idea that sex is a strictly private matter is incredible. Yet it continues to exert a powerful force.

Scientific frankness. This came, oddly enough, through the subscientific writings of Sigmund Freud. He taught that our sexuality is fundamental to our nature; that enormous instincts of repression govern our sexual nature; and that by exploring our unconscious thoughts we can remove the power from our obsessions. The original Freud is a profound mixture of imaginative insight and error. Freud as popularly understood is something else again. Common people heard that any limit on sexuality was psychologically stifling; it might even make you insane. It became daring and healthful to throw off sexual repressions. This climate enabled Alfred Kinsey to ask “personal” questions in his famous studies, and eventually enabled Masters and Johnson to investigate human sexuality as mere biology.

The scientific approach tended to make sex more a “thing” that could be studied, broken down into its components, manipulated, even altered. Sex seemed less mysterious if understood as a complex of urges and hormones and environmental nurturing. The atom had been tamed; why not sex?

Media exposure. Since the invention of the printing press, the forms of public communication have proliferated so that people rarely escape them, whether in their living rooms, their cars, their workplaces, or their bedrooms. It is rare to encounter any of these media, even briefly, without encountering some overtly sexual appeal. We now barely notice it.

In earlier times, a person could go through the day without seeing or hearing any mention of sex, unless it was from his spouse or from some friends of the same sex. Today, any one of us encounters sexual suggestions many times a day, nearly always from someone whose very existence is the figment of an advertising director’s imagination. We live in a constant bath of depersonalized, imaginary, highly provocative sexuality. To the modern person, this seems normal.

Existential schizophrenia. Reality and personal meaning have strayed poles apart, resulting in a curious schizophrenia. What is “real” has become what is scientifically verifiable. Thus, if Masters and Johnson discover certain physical symptoms that go with orgasm, these must be real. They are also meaningless. Since love, purpose, and passion cannot easily be quantified or broken into their constituent parts, they are not “real.” They are only accidentally, fancifully joined to “real” things. But they are “meaningful.”

This schizophrenia shows up in many discussions, but particularly whenever sexual morality comes into question. Moralists (or antimoralists) can say things like, “We need to separate a person’s actions from his intentions.” In fact, that is exactly what the presiding bishop of the Episcopal church recently wrote to his bishops: “In my view, we would be helped [in discussing genital sex outside marriage] if we could separate two concepts which I believe are often not made distinct. The first is values. The other is behavior. I believe that the Church must have a common mind on the essential values.… However, no matter how we are united on our values, there will be a variety of expressions which proceed from these values. I do not believe it is necessary or possible for every individual to establish the same behavior.… What I perceive happening is that many are not separating these two concepts—values and behavior. There is great conversation about the actions but little comprehension about the root values.”

It is not hard to infer where this pattern of thought can lead. Values such as “love” and “community” will be applauded; and their application will be left up to individuals (emphasizing the need for a believing community to serve as the conscience for individuals). Actions are real, and can be studied by doctors, sociologists, and other dispassionate observers; but only intentions by this logic may be morally meaningful. If a person’s intentions are loving (or “unitive”), then their meaning is profoundly good.

While the distinction between values and behavior is often helpful in ethical thinking, in the area of sexual ethics it is sometimes a smokescreen for permissiveness. Jesus carefully taught us the moral significance of intentions, but he spoke at least as often of behavior as values. In matters of sexual behavior, good intentions may not be enough.

The rise of therapeutic values. The values that a counselor adopts in a limited, therapeutic setting are becoming those of society at large: to accept people as they are, to be sympathetic as you help them understand and accept themselves, to assist them in making their own choices. These are quite distinct from more traditional values, which clergymen once were known for: to teach people to want to be right, inwardly and outwardly; to help them to measure themselves against God’s standards; to foster the choice to love and obey God and to discourage any other choice. The moralist is a surgeon, cutting away cancerous tissue. The therapist is a midwife, optimistically assuming that amid the chaos of any life something is being born, something that only needs assistance.

The therapeutic model has great pastoral value. It has helped many; in some respects it follows the pattern of God’s grace. But isolated from a moral context, it loses any true sense of kindness: for what is kind about accepting behavior that is neither right nor wrong? The therapist’s work is never really isolated from a moral context. The therapist sits alone in his office with a client, yet is aware of society outside. A family, a spouse, an organization or business expects certain standards of behavior; the therapist provides a 50-minute refuge from society’s judgments in order to explore the reasons behind, and the possibilities of, escape from whatever is making his client unhappy.

The combined effect of these changes—secularization, privatization, increased frankness and the growth of communications media, and so on—makes a Christian witness on sexuality extremely difficult. Assumptions are just that: assumptions. When we are talking about a concrete issue—say, sex education in the schools—a great deal of what Christians say gets ignored or misinterpreted, simply because our assumptions are unthinkable to many modern people.

For example, Christians will never be happy with “value-free” sex education. We do not believe in secularism. For us there is no “religious realm.” God, we think, is part of any subject. While we may agree to teach, say, mathematics without any explicit reference to God, we know that the silence is arbitrary. The teaching of mathematics contains implicit assumptions that we recognize as our own; the belief in truth and error, for instance. “Value-free” sex education contains implicit assumptions that we disagree with—the assumptions that sexuality can be treated “objectively” and “biologically” and that persons and their values are an optional, additional consideration.

We are a vulnerable people, seeking a way to appreciate God’s gift of sexuality while guarding against its dangers. Our vulnerability is increased by the sexually saturated environment we live in: a society that wants to see only sex’s goodness and not its powers of destruction. Thus society holds presuppositions very different from our own, which make dialogue difficult, and which often increase the confusion Christians feel.

Our vulnerable confusion is not just abstract and intellectual. It affects the core of our lives: our aloneness and our love, our hopes for family, our sexual pleasure. The real world of sexuality is very unlike Playboy: it includes tragedy, loss, and aloneness, along with comedy, pleasure, and triumph. Vulnerable people need wisdom.

What Do We Want?

Joanne is a striking brunette who heads data control for a large food distributor. She took several years to accept her divorce, for she had really loved Nate. They reunited several times before giving it up for good.

Now she is quite cynical about the conservative sexual ethics she grew up on. “It’s hard to believe I swallowed that whole line,” she says to her friend Ruth, who has met her for coffee one Saturday morning. “When I think of the energy I put into saving my virginity, it amazes me.”

For two years now, Joanne and Hank have been together. Once, when he developed a stomach ulcer, she moved in with him, but feeling not quite right she went back to her own apartment when he recovered. Hank teaches ethics in a business school, and is sometimes quoted in Newsweek. Everybody likes him, and Joanne feels fortunate to have him. Or almost to have him. Now and then, Hank spends a weekend with his former wife. And once he took a working vacation with his secretary.

“I guess it bothers me,” Joanne confesses to Ruth, “because my biological clock is ticking. Oh, maybe I am a little jealous, but I can live with it. However, I would like to have kids, and I think Hank would make a wonderful father. I just don’t feel settled. I certainly don’t feel solid enough to go ahead and have a child. Do you think that’s just an excuse? I mean, do you think my upbringing is getting to me?”

What does Joanne really want? A husband and a house in the suburbs? A child? A closer relationship? An exclusive hold on Hank?

What do any of us want? Our desires are broad and ill-defined. Rarely do we know exactly what we want until we are given a specific set of choices. In modern America, the choices for sexual activity are wide. Yet for Joanne—as for anyone—the implications of the choices are very deep.

Still, can’t we simply live and let live? Isn’t it possible for each person to pursue his or her own sexual ideal? Yes, but only to a limited extent. The idea of a society filled with autonomous individuals, each freely choosing his own pattern of sexuality, is a myth of the late twentieth century. Such a society has never existed and can never exist. Our desires and expectations take form in a social environment, and there is no such thing as a neutral social environment. To some degree society must collectively decide, and continually reaffirm, an answer to the question “What do we want?” Anthropologists find societies that believe and practice a wide variety of sexual ethics; but they do not find societies that have no belief and practice. Right now America’s definition, like Joanne’s, is decidedly vague. We are in transition.

What do we want? Because we do not instinctively know with much precision, we look for some authority. Much helpful study has been done by psychologists and anthropologists, and Christians have much to learn from these authorities. But this knowledge is inadequate in and of itself. When looking for authoritative direction on human sexuality, Christians must turn to the Bible. And that is no wonder. Sexuality gets to the core of who we are, which God alone knows.

Perfect Sex

The biblical description of sex begins with an image of perfection: the Garden of Eden. What should we want? We should want to recreate this garden, with its atmosphere of perfect freedom and intimacy. (In fact, the promise of Christ’s new kingdom suggests we can expect something better than Eden.)

In Eden, God made human beings male and female in God’s image (Gen. 1:27). This implies equality between the sexes. Neither one sex nor the other is God’s image; both are. Further, their sexuality is not irreligious or immoral; in God’s image they are male and female.

Genesis’s second chapter tells more about how this came to be. Having made all the other creatures, and having found everything good, God found Adam’s aloneness “not good.” To correct this, God created Eve as a suitable complement for Adam.

Then, in three short verses (2:23–25), Genesis provides a positive understanding of the relationship of men and women. First is Adam’s cry of delight: “This is now bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh; she shall be called ‘woman,’ for she was taken out of man.” The emphasis is on the similarity of male and female (particularly in contrast to the other animals, who were not found to be suitable complements). Male and female are called together because they are alike. They are alike in that both are made in the image of God; therefore, they can commune with him and with each other. Clearly the two are different; they were even created differently. Yet any attempt to treat the sexes as utterly different species runs into this verse. The two are alike, right to the bone. This is profoundly good, because God made it so, and Adam greets it with joy.

Second comes a comment on marriage, which would be quoted by both Jesus and Paul: “For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and they will become one flesh.” The emphasis is on the couple’s unique oneness, which requires a separation from all other family ties. This verse is not a comment on Adam and Eve, who had no father and mother to leave, but on the reason why the creation of male and female has led to marriage. In the face of the call to communion between the man and the woman, all other social ties are relative.

The third aspect of this foundational view of the relationship of man to woman is the eloquent description of the original intimacy: “The man and his wife were both naked, and they felt no shame.” God meant men and women to be together in shameless nakedness. We ought to desire this. In fact, we do.

God did not command Adam and Eve to be naked and unashamed. It was their nature to be so. In the complete freedom of Eden, they did what they wanted, and what they wanted was to be together. Without the aid of legal or social props, they were intimate, naked, and “one flesh.” The only “not good” in the universe (man’s isolation) became “very good.”

To this intimate pair God gave commands to procreate and to rule the Earth. Some have emphasized these tasks, as though the chief reason for marriage was to raise children (“be fruitful and multiply”) and form the traditional family economic unit (rule the Earth). It would seem, from the evidence in Genesis, that although procreation is the primary purpose of sex, the secondary purposes of pleasure and social bonding are sufficient justification for sexual activity.

Why were we made male and female? The two were created to obliterate aloneness. They were to become one flesh, naked and unashamed. In this communion they had opportunity for children, for intense sexual experiences, for companionship and for partnership. Primarily, though, two people were to become one flesh. That was reason enough for them to be together. Nothing short of death will ever separate such a pair. No other love will compete, save for the ultimate love and devotion to God.

From Eden To Sinai

The early days of Eden hardly form a sexual ethic. Hugh Hefner could affirm shameless nakedness as readily as could John Calvin. But the Bible soon leaves Eden and goes on to Sinai: “Thou shalt not commit adultery.”

Why is it that Christian sexual ethics show this stern and moralistic side so predominantly? People like Joanne warm to the emphasis on love and communion, but bristle at all sentences beginning, “Thou shalt not.” Are such commands necessary?

They are, because we are now unable to experience Eden’s love and communion except under the rarest of circumstances. It is no longer natural to us to be naked and unashamed. In fact, it is more natural for us to abuse our sexuality and break our communions. So we take vows against our fallen nature: the vows of marriage.

Chapter 3 of Genesis describes how Adam and Eve’s natural union fell apart. They rebelled against God together, remaining “one” in their sinning, but then immediately turning to blame each other. They became ashamed before each other, and put on clothes. As a result of their rebellion, God pronounced punishment on them, punishment that would make the commands to multiply and rule over the Earth difficult to fulfill. Childbirth would be painful. Farming would be disagreeable labor, for the land would not cooperate. And Adam and Eve’s intimacy would be strained by male domination: “Your [Eve’s] desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you” (Gen. 3:16).

Yet they stayed together and had children. They were no longer shamelessly naked together; their natural harmony was broken. Fortunately, however, not everything was lost. Adam and Eve retained the hope of regaining what they had lost. So did their children, and their children’s children. So do we. Most of the Bible’s sexual ethics are meant to protect marriage so that within its boundaries some of the unashamed nakedness of Eden can be realized again. In fact, it is only through the Bible’s sexual ethics that man and woman can truly enjoy their sexuality.

Marriage, the author of Genesis says, grew out of Adam’s original, joyful response to Eve: “Bone of my bones, flesh of my flesh.” Jesus’ comment is helpful: “What God has joined together, man must not separate.” That is to say, God still joins together. The inflexible ethics of the Bible aim to keep us from breaking such God-given unity.

This unity affects much more than social conditions, such as the preservation of the traditional family. It mightily affects our view of God and the universe. Church historian William Stafford says, “If I perform a succession of one night stands with different people, that tells me at a deep level of my being that ultimate reality is inconstant, has no covenantal or continuous quality to it. The bottom line is that God is not faithful. You can’t expect the universe to be the same for you tomorrow as it is today because it will change characters on you. That’s why I think all through the Scriptures there are references to illegitimate sexual acts as being related to idolatry. Through marriage, you teach who God is to yourself in a very deep way.”

But why marriage? As some wag has said, marriage is a great institution, but who wants to live in an institution? Why not emphasize something more positive, like love? The difference between the institution and Eden is well shown in the traditional Christian vows, where the couple promises fidelity “for better for worse, for richer for poorer, in sickness and health, … till death us do part.” If that were all marriage were about, surely no one would marry.

The institution is tough-minded, designed to protect the ideal through lifelong, loving fidelity. Fidelity does not guarantee communion. Couples can coexist under the same roof for 50 years, yet experience very little genuine unity. But communion is impossible without fidelity. “Bone of my bone” cannot pick up and go its own way; “one flesh” cannot separate without tearing.

Fidelity also fosters the growth of communion. It does that by leading our wandering attention in one direction. It challenges the forces that would distract us (other commitments, such as parental loyalty or career obligations) or compete with lifelong communion (adulterous impulses). The marriage commitment demands that we stick to each other until death because fallen people lack the natural stability to do so. The marriage commitment demands exclusivity because fallen people grow confused by competing impulses, which diffuse their intimacy. The marriage commitment demands sharing all that we are and have because fallen people are selfish, and withhold from each other. In short, the institution of marriage, known by its demands and commitments, forms a protective cradle wherein unity can grow.

The Sexual Commandments

Of course, the Bible does little to define marriage. It offers no standard vows, no ceremony. Two commands, in particular, dominate Old and New Testament sexuality: “Do not commit adultery,” and “Do not covet … your neighbor’s wife.”

Again, this is the side of biblical sexuality that many have rejected. The law does not begin by telling husbands and wives to love and cling to each other. That would be easily twisted to suit our fallen nature. The woman who has an affair insists, quite sincerely, that she deeply loves her husband. She might perceive herself to be obedient to laws that called her to love her husband. But the law specifies that you should not want and not have anyone but your spouse. This protects us from rationalizing our way into adulterous episodes that we wrongly think do little harm to the marriage bond.

It is certainly true, as many commentators point out, that in the Old Testament these laws were expressed in a patriarchal, polygamous culture where husbands had the right to take as many wives as they wished and to divorce as many wives as they wished, and where women were treated as property. The Old Testament is generally uncritical of that social situation, even though Genesis 3:16 suggests that it was a result of sin and, at times, provided certain rights for women. The law is preoccupied with another concern: constancy and exclusivity within marriage. Other men’s wives were not to be wanted or had. If a man wanted and had an unmarried woman, she became his wife, according to the laws in Deuteronomy 22. A man’s only sexual options were with his wife (or wives).

We do not know much about the quality of intimacy that developed within Israelite marriages. We certainly have evidence in individual cases (Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, Jacob and Rachel, Elkanah and Hannah) that some marriages reached closer to the Edenic ideal than mere economic and procreative convenience would require. At a few points—in Proverbs, and particularly in the Song of Songs—the ideal of unashamed nakedness reappears with startling force. Yet the central ethic of sexuality is negative—against adultery. Sexual intimacy is only permissible within marriage.

The same may be said of Jesus’ sexual ethics. He apparently said relatively little about marriage and family life. When he did speak (Matt. 5:32), he closed the divorce loophole, making it clear that any remarriage was adulterous. This means that not only do Christians regard adultery as wrong, they also regard “serial marriage”—repeated divorce and remarriage—as an unacceptable substitute for the ideal of lifelong, committed union. It may be that, in our tragic world, serial marriage is an inescapable evil because of the hardness of our hearts. But what appears to be necessary in tragic circumstances should not be confused with what has been lost in Eden.

If there is any clear message to help protect the vulnerable from themselves, it is this: There should be no adultery. No competing relationship should be allowed to “adulterate” the unity of husband and wife. Among the confusion of many choices, this has no confusion. With our endless ability to rationalize and justify, we can deceive ourselves about the quality of our marriages or affairs. Yet there is no such deception with adultery: you either commit it or you don’t. A society that stops adultery will always have deeper communion between husband and wife than the same society that finds ways to legitimize adultery.

Adultery Of The Heart

Jesus also spoke of lust, “adultery of the heart.” Sometimes this is viewed as Jesus’ innovation, an addition to the Old Testament Law. But the idea that adulterous thought as well as adulterous action is wrong originated in the tenth commandment: “You shall not covet your neighbor’s wife.” (It was, and is, easily overlooked by people preoccupied with technical righteousness.) The concern for thought as well as action shows that more than property rights were under consideration in the Old Testament. Coveting another man’s wife, or lusting after a woman, does no harm to another person’s property. It harms the one who lusts, by confusing and diffusing the shape of his chief desire.

This command goes hand in hand with the command against adultery. Thought and action, character and performance go together. To foster shameless nakedness, it is not enough merely to do the right things; one must desire the right things. The command not to lust tells Martin Nestor, looking jubilantly at his brochure, that his self-confidence that “nothing will ever happen” is quite wrong. Something has already happened. His desire has gone astray.

There is surely a great difference between the sexual excitement generated from seeing or imagining a physically attractive person, and “coveting your neighbor’s wife.” Defining the difference, or where the line should be drawn, is not so easy. On one hand, we must say that sex is good, and that all personal interactions have an appropriate sexual dimension. It is difficult—perhaps impossible—not to notice the sexual attractiveness of another person, especially in a culture such as ours where sex has become an effective marketing tool. On the other hand, we do have some control over what we desire, and a responsibility to train our desire toward one beloved. The command against lust reminds us that we are fallen creatures in a fallen world; we cannot escape the mire of wrongful desire because it is so intrinsic to who we are. Yet we do not despair; rather, we thank God for his forgiveness, and ask his help through the Holy Spirit to turn our love and desire more deeply and constantly toward the beloved he gives.

Casual Sex

The New Testament offers a third command on sexuality: against porneia. The actual Greek word has a less-defined meaning than our English “fornication.” (Thus newer versions usually translate it “immorality.”) Author Donald M. Joy understands porneia to be sexual commerce, in which intercourse is traded for pleasure, money, status, or other goods, rather than as an expression of deeply bonded love. Lisa Sowle Cahill writes that the word “can signify a range of meanings: prostitution,’ ‘fornication,’ ‘unchastity,’ ‘indecency’.” Christian ethicist Lewis Smedes calls it a “blanket word” that can mean infidelity in marriage, as well as homosexual behavior and premarital sex.

This uncertainty as to the word’s precise meaning raises questions about whether two unmarried people, deeply in love, can be accused of porneia. We shall return to that question later.

It was not an issue that arose in New Testament society, when long, unchaperoned courtships were apparently unknown. What the word certainly does refer to is casual sex—for instance, sex with a prostitute (1 Cor. 6:16–20).

Why is porneia outside the boundaries of Eden? It is, in the case of the prostitute, strictly impersonal, and would not seem to compete with the marriage bond at all. Or why, in a more modern situation, is it wrong for college-age kids to experiment sexually and develop greater sexual awareness? Later on they can marry and be faithful, but for now, why should they not fulfill their sexual needs?

Paul’s vociferous answer in 1 Corinthians 6:12–20 claims that even the most casual sexual coupling makes two people “one flesh.” Smedes is eloquent on the subject: “It does not matter what the two people have in mind. The whore sells her body with an unwritten understanding that nothing personal will be involved in the deal.… The buyer gets his sexual needs satisfied without having anything personally difficult to deal with afterwards.… But none of this affects Paul’s point. The reality of the act, unfelt and unnoticed by them, is this: it unites them—body and soul—to each other.…” This is what Paul means when he writes of porneia: “All other sins a man commits are outside his body, but he who sins sexually sins against his own body” (1 Cor. 6:18). He means that sexual intercourse is not external to you; it affects you to the core.

If Paul is right, then sexual intercourse is not one thing to one person, something else to another. It is not a symbol that we fill with meaning, according to our choice or according to our age or social circumstances. It already has a meaning, which we disregard to our peril. Extramarital sex is not only wrong when it violates a marital covenant; it is wrong even when no marital covenant is in view, because it is an expression so potent it is appropriate only within the marriage covenant. Everywhere else, it is out of place—like using the Lord’s name in vain.

We might put it this way: Someone who has given himself sexually has less of himself to give to the love of his life. In a purely practical sense, he has memories, expectations, lessons from his experience; and these lessons go to the root of his character. We might put it another way: He is no longer a virgin. In our current social climate, it is difficult to remember what people once found so favorable about virginity. It once meant innocence, naïveté, expectation, openness. The virgin is unformed by experience. Thus virginity is of value primarily because it leaves the way open to the right kind of sexual formation: within marriage. Virgins have a greater openness to communion.

So the command against porneia also implies the possibility of undiluted communion between a man and a woman—the kind of unashamed nakedness that can (or should) never be broken. In a society where casual sex is acceptable, this kind of communion will grow rarer and rarer, for people’s capacity to give themselves to each other grows smaller.

That is why “Thou shalt not” is such a prominent aspect of the Bible’s sexual ethics. The law cannot save us. What it can do—indeed, what it is intended to do, and what nothing else can do—is to form a defensive rampart around a state where law has little effectiveness. Biblical laws against adultery and porneia, in particular, assure that we will seek unashamed nakedness only under conditions where it is possible: with one person, throughout life. The law protects us from our own capriciousness and self-deception. It assures that we will not be discarded at a certain age, as an increasing share of American women are. (An American man who divorces and remarries, according to George Gilder, will marry a second wife ten years younger than his first wife. Largely because of this, divorced women in their forties are likely to remain alone.) And, one must add in this time when sexually transmitted diseases (STD’s) have far outstripped medical cures, the law protects us from disease, so that our sexuality will not become the source of our death.

While biblical laws protect something desirable, they are not in themselves attractive. Methodist pastor William H. Willimon writes, “Every time I stand before a couple and recite the words ‘for better …’ I declare the outrageous proposition that happiness is neither the goal nor the promise of marriage. Both Christianity and marriage teach us that life cannot be chiefly about happiness. If life is learning how to tell the truth and how to receive strangers, then how on earth can life be about happiness? For neither truth nor hospitality occur without some pain.”

Marriage, then, is one means by which God would restore us from the effects of the Fall. It is not an easy path to follow. Indeed, its hardness reminds us there is no salvation without suffering.

Undisciplined Yet Unpunished

These biblical directives make sense until we notice that some people violate God’s laws for sex and seem to suffer little for their indiscretions. Every Christian has friends who have broken these laws and yet fare well: who fooled around for years and yet form model marriages; who left one spouse for another and seem to have achieved greater intimacy; who rejected marriage entirely and seem untroubled by their sexual relationships. The law may be unconfused, but the results are ambiguous. So the person who is tempted to disobey—to commit adultery, or indulge in pornography, or experiment sexually—cannot see any clear-cut reason not to. Everyone else is doing it—and everyone else seems to be doing fine.

This is recognizably the situation with most laws. Thieves do not steal expecting to be caught; they steal expecting to enrich themselves, and often they do. We teach children not to steal largely because a society of thieves is one that we, and they, would not want to live in. Similarly, we teach children rules of sexual behavior—and follow those rules ourselves—partly because of the societal impact of those rules. If a very large slice of society is adulterous or promiscuous or lustful, the effects will be obvious in society (indeed, they are obvious) even though they are ambiguous in countless individual situations. In fact, many of the social problems we now face—the feminization of poverty, the plague of AIDS and other STD’S, the increase in single-parent families, the degradation of women and of sex in mass media, the huge number of abortions—are related directly to the sexual ethics that guide our behavior. Is it right for an individual, in making his decisions, to ignore the social implications of such ethics—to pretend that sexuality is a private matter? The message of the Bible and the record of human history agree that such a notion is mere fantasy.

But even the individual, operating only in his own self-interest, should take warning. There are unpredictable effects in sexual behavior. We do not know who is vulnerable and to what. There are unseen, spiritual effects. If someone should grow callous to loving and discarding a series of partners, he or she may grow callous to life in general, and yet seem to be doing fine.

The individual should also consider what effect his action has on children. Today the old double standard between men and women has been largely discarded. A new double standard involving children and adults has emerged. We tell teenagers they are “not ready for sex,” knowing full well they are physically capable of enjoying intercourse. Yet we do not require adults to attach more than a physical dimension to their sex lives, except perhaps to be reasonably certain love is present. Whether this double standard is morally correct is almost irrelevant: It does not work. You can never get a teenager to believe that what is right for an 18-year-old is wrong for a 15-year-old—especially when it regards an activity that the 15-year-old wants to do as much as he ever will, and when he feels the morally justifying “love” as much as he ever will feel it. Statistics have shown a persistent tendency for American adolescents to engage in more sex at an earlier age, to the point that as many teenagers have first sexual experiences before 16 as have them after 16. When we make decisions about our sexual ethics, we do not act only for ourselves; we are always teachers of our children.

There is another, more important reason for obeying biblically grounded sexual rules: They are right. They are built, not on pragmatism, but on an ideal. Whenever someone disobeys these rules, through adultery, casual sex, or lust, he forfeits the ideal. He may not suffer obvious harm, but he does suffer loss—loss of Eden. Unashamed, one-flesh intimacy happens only in an exclusive, lifelong, loving covenant. When you leave that, you cannot return. Then you cannot, by definition, be right. You can only be said to have missed the target. Christian sexual ethics is inherently idealistic. We hold up an ideal of communion that is far from convenient. Few will experience it fully. Most will suffer trying to attain it. Yet it is worth the pain, because it is what God made us for in the garden.

Starting Over

Of course, many marriages will never match that ideal, perhaps because the husband and wife are poorly suited to each other, perhaps because of some psychological damage done early in their lives. Is there a time when, in seeking the Edenic ideal, we must write off a relationship and start over? Should some marriages be judged a failure?

Inevitably, some marriages will be judged a failure. The topic of divorce and remarriage is beyond the scope of this article, but it is worth noting that most Christians regard separation and/or divorce as permissible, even necessary, in some cases. And many Christians accept remarriage in those circumstances. However, two things should be said.

First, these broken bonds must be accepted as tragic departures from what God has intended, and not as the norm. They should grieve us deeply, because they represent a terrible loss.

Second, we ought to be very conservative in regarding a marriage as a failure. A failure at what? At forgiveness? At persistence? Our faith suggests a different standard of success and failure than our surrounding culture’s. Was God’s marriage to Israel to be judged a failure? And how should we judge his marriage to our present-day church? Certainly, it fails. But God’s powerful love makes a triumph out of death, a marriage out of harlotry. The gospel of hope declares that in Christ failure is temporal, victory is certain. In some marriages, the struggle itself may be a powerful sign of the kingdom.

Words Of Hope

Peter and Marge speak of their marriage as though it were a huge, intractable object—as they might speak of a defunct grand piano in a second-story bedroom. As intelligent, educated people, they are usually above blaming each other for their mutual unhappiness. So they blame “our marriage,” as though it had an independent existence.

And indeed it sometimes seems to have. Peter is a highly successful engineer. He deals with design problems in an energetic, systematic way. As he has risen on the corporate pyramid, he has applied himself to management technique in the same way he solves mechanical problems, and with the same success. However, while he has been to seminars, has read books, and has been in counseling, he still does not know how to fix “our marriage.”

Marge is herself a counselor. She has an instinctive way with people, which has made her extremely well liked wherever she has gone. She is not, any more than Peter, used to frustration. Her life is a great success, excepting “our marriage.” Both Peter and Marge are committed to making it work. But after five years of stalemated unhappiness, with little joy and almost no sex, that looks more and more grim.

Jesus’ words are unequivocal to Peter and Marge: They are married for life. To escape and start over amounts to adultery.

Those hardly seem to be words of hope. Where, and how, in their sexual lives may they hear the words of Jesus, “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest” (Matt. 11:28)? They have done everything, and yet they are miserably unhappy. Can their marriage be saved? Can any marriage be saved?

We usually speak of “saving a marriage” as merely keeping it intact. But salvation is more than survival. Many couples have stayed together and yet remained far from Eden’s unashamed, delighted nakedness. For Peter and Marge, or any couple, we should want more than grim coexistence. We should hope to see God’s grace penetrating deeply into their emotional, spiritual, and sexual lives.

Sexual Salvation

Psychologist Kaye Cook reminds us that “sexuality is basic to our sense of ourselves as God’s creation. In the secular world sex has become a thing, an activity. It’s almost separate from you.” A Christian sexual ethic, on the other hand, views sexuality—life as male and female—as an integral part of every experience. It does not wait for puberty to begin. It is not measured strictly in orgasms.

Because sexuality is so central to our being, the Christian concept of salvation must include it. We have wrongly relegated salvation to a strictly spiritual realm, willingly turning our souls over to God, but trying to save the rest of our being through our own good works. But God does not save our spirits and leave our bodies behind. Every part of us must be redeemed.

Sexual salvation is Christ’s work in our sexual lives, to bring us closer to the Eden he originally planned. It is sexual fulfillment, but not as the world defines it. Modern Americans evaluate sexual fulfillment by how good they feel. Christians must take a wider view, considering how sexual people will serve in the kingdom of God. Sexual salvation is one aspect of God’s redemptive work. He sets us free from the powers of destruction and allows us to become, as God’s people, all he meant us to be. Such salvation will certainly feel good, but it will also call us to a higher quality of life than we might invent for ourselves, and it will call us to greater sacrifices than we would quickly choose.

Receiving The Gift

But how do we receive sexual salvation? That is what Peter and Marge want to know. They are burdened by their sexuality, their inability to relate to one another as one flesh. How can their relationship be transformed?

Single people, similarly, ask how their aloneness may become a gift and a sign of Christ. How, they ask, can we be sexually saved?

“Not by works, so that any man may boast,” but only through a free gift of grace. This is a way of saying that no rules, no therapy, no techniques can of themselves save a marriage. In the same way, no rules will enable a single person to mirror the freedom of the kingdom of God. Sexual ethics lead us to this grace, but they never produce it. In fact, if sexual ethics pretend to offer this grace, they actually war against it. So it happens when any community becomes obsessed with its sexual rules, whatever they are.

For Peter and Marge, Christian ethics will warn them against an escape from their crisis. This is a crucial prelude to sexual salvation. There are, most Christians agree, some grounds for divorce; however, divorce is not salvation but an admission of defeat. Staying in a marriage makes both unhappy partners daily consider their need for salvation. Perseverance is a sign of continued hope, however dim. Sexual ethics will urge them to communicate with each other, to empathize with each other, to forgive each other, to persevere in love for each other. Yet sexual ethics will also frustrate them, because they will not be able to live as they please. For Peter, sexual salvation will not come as Marge is transformed into his personal version of the Total Woman. It is more likely to come as he discovers that his maleness and his wife’s femaleness are a unique gift from God that contributes to personhood, even as it sometimes causes struggle and suffering. No one can prescribe exactly how this discovery occurs. It is found only in Christ.

What will they find in Christ, and what will it have to do with their marriage? They will find—all will find—at least this:

They will find healing from past wounds.

They will find forgiveness for past sins.

They will find an example—a living, present example—of sacrificial, covenantal love.

They will find a purpose that lifts them above themselves and their narrow preoccupations.

They will find joy and peace, which radiate from the presence of the Holy Spirit.

They will find patience to persevere in difficulties.

They will find strength to control their own impulses.

Saying that sexual salvation is found in Christ also suggests that Peter and Marge will not find it alone, but in the body of Christ. That, after all, is where Jesus promises to show himself. In this body they will hear the gospel of forgiveness—as important a message for our sexuality as any there is. In the body they will be prayed for, they will receive the sacraments, they will worship and sing to the One who loves them above all others. In the body they may find the specialized pastoral care that therapists offer to persons who want to regain the beauty of Eden within their marriages.

Of course, churches often fall short of this ideal. You will not find them peopled with sexual paragons. Yet the church’s singular gift is to offer Christ to any who want salvation. We wait for his coming, and the fullness of our sexual salvation.

We wait. Christians have always emphasized that our salvation, while it is sure, is far from completed. “If only for this life we have hope in Christ, we are to be pitied more than all men” (1 Cor. 15:19). So it is with sexual salvation. Our world demands it immediately, and since it cannot have it immediately, uses various routes for escaping sexuality. What can divorce, promiscuity, and pornography be but escape? Christians are called not to escape, but to wait for salvation.

Peter and Marge may—indeed, with help they almost certainly can—achieve some measure of marital improvement. But can they learn enough to achieve what they so urgently want? Not by the law. It will come only through the surprising, unpredictable gifts of a loving God. Peter and Marge, and all of us, are put in a dependent situation. We do not like this. We rebel against it. We want to schedule God’s surprises.

Our schedules have nothing to do with the call of Christ: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” He does not explain when and how he will do it. He merely promises that he will do it, for those who come to him, sit at his feet, and wait for his salvation.

Peter and Marge may, in fact, already be experiencing Christ’s salvation in their marriage. Are they learning the meaning of sacrifice? Are they learning patience? Are they learning fidelity? Are they learning trust in Christ? We need not suggest that sexual salvation is only found in such difficult lessons. But it certainly includes them. The natural desire is to run from the struggle, postponing the agony of unfulfillment. Salvation, with its promise of freedom, comes to those who wait.

Therapy For Healing

In waiting, we become open to God’s work, which often comes through others. And one of the more hopeful vehicles of his grace has been the appearance of Christian counselors trained to help couples who cannot enjoy sexual relations. In such cases, technique often is less important than attitude. When therapist Balswick lists characteristics that she and her colleagues have found helpful in working with troubled couples, she begins with self-acceptance and body awareness. “Couples need to develop attitudes of flexibility, openness, unselfishness, as well as a mutual ability to allow each partner to give pleasure to the other. They also must be willing to communicate with each other about their sexuality—to explain what feels good and what they desire.”

Ideally, Christians gain these qualities through a lifetime of relating to others. But the ideal is frequently shattered by unfortunate episodes on the journey to sexual salvation: childhood sexual abuse, inadequate sex instruction in the home, broken relationships within the family and without, changing values and mores in an increasingly sex-obsessed culture, and confusion over the role of sex in courtship and marriage.

When mistrust is learned, it is not easily unlearned. But in a loving and persevering environment, it can be. Sexuality is a learning experience—a process of play, of drama, of ecstasy, of frustration, of small passing touches as well as passionate lovemaking, of conversations over breakfast as well as under the moon. Most of these learning experiences apply to unmarried people as well as married. All of them can be encouraged and strengthened by other Christians, and supplemented by the wise counsel of Christian therapists.

Such therapy has been enormously helpful, particularly when Christian therapists and counselors understand there is more to sexual salvation than proper technique and attitude. To the secular mind, sex is meaningless. Secular therapy aims to help people adjust happily to their sexuality, as indeed Christian therapy often does. God’s work in our lives does not end even when we have become secure, aware, and thankful for our sexuality and the sexuality of others. The Bible calls us to terms with the dramatic changes being brought into the world through the redemptive life of Jesus. Our sexuality is only saved insofar as we relate it to this. “In the area of sexuality in particular,” Lisa Sowle Cahill writes, “Christian ethics has been characterized by an unfortunate, and unbiblical, ‘bottom line’ mentality: precisely which acts are permissible for whom, and under what circumstances? Biblical authors, to the contrary, mention moral acts only in connection with the faith orientation that they express. Paul’s approach to sex, celibacy, and marriage is instructive, because he sees them as manifestations of the sort of life a religious community and its members have achieved.

Sex And Singles

Rose was never a pretty girl. She grew up on a farm far from other boys and girls her age. She was shy, and since she had chores at home she never participated in after-school activities. She went through college without ever dating. When she finished college she took a job in Washington, D.C., working in a congressman’s office. The hours were long and she did her work quietly and well, but not so well that anyone took special notice. She had a small apartment just outside the Beltway; she took work home and watched TV in the evenings.

That was her life for 11 years. Something is happening, however, between her and Tom, the apartment manager. He has been lavishing attention on Rose. He calls her up. He asks her out for dinner and kids her when she blushes.

He invited her up to watch a movie on his VCR. She bought potato chips and made a dip to bring along. When they sat down together on the sofa she did not recognize immediately what kind of movie she was watching; she thought it was just poorly acted. It was pornography. She was too embarrassed to protest. She grew fascinated, then flushed with excitement. Before the movie was half over she and Tom had intercourse.

She did not for a moment feel guilty, only astonished. Now she and Tom get together regularly to watch movies. She cooks dinner for him, and then without a romantic word he puts a tape in the VCR. He has never mentioned what he thinks of their relationship, or what plans he has in mind. She thinks about that sometimes, but she will take a wait-and-see attitude. The pleasure of being desired is what matters most to her. She feels as though until now her whole life has been full of nothingness. Though this terminology would never come naturally, Rose feels as though she is being sexually saved.

How can Christians play Scrooge to Rose and other unmarried people? For the most part, single persons want what anyone else wants: they want not to be alone. They want to bond as one flesh with others. They want to come to terms with the sexual nature they feel. To many of them, sexual intimacy seems to be a fundamental human need. It certainly is a fundamental pleasure. Some, like Rose, have never had the opportunity to marry. Others have chosen not to marry, or to defer marriage. Some are divorced. Some are widowed. Some are homosexuals. Must they be denied the joys of sexual intercourse?

Christians have been most successful in recent times at portraying the desirability of lifelong, loving marriage. Of course, this success cannot be taken for granted; just ten years ago traditional monogamy seemed to be in trouble. Today, however, most people seem to have lost interest in “alternative” marriages. Even childbearing has regained part of its traditional prominence.

But what about those who are unmarried? Here, traditional Christian ethics has been almost entirely overwhelmed. A small percentage of those who marry in America are virgins. “Living together” without benefit of clergy has become a mundane practice; and sexual intercourse has become very common in serious relationships between single adults.

For unmarried people, sex is sometimes called “experimentation”—a revealing word that emphasizes the tentative, uncommitted, speculative stance of the experimenter. He or she, like an experimenter, hopes to discover something—ideally, a lasting relationship. Replacing the traditional fear that unchaperoned dating might lead to something—that is, to sex—is the modern hope that sex will lead to something—that is, to marriage.

Do Christians have any better hope to offer Rose?

Naked And Alone

It will not help to make Rose feel guilty about her relationship. If we did, she might retort that she feels guilty for 11 wasted years.

Should we tell her that, regardless of what she feels, she was better off before? That because she was a virgin, she was good in God’s eyes? No. We do not need to endorse her past life any more than her present life. The way Rose was living before she met Tom was not good. God does not intend the unmarried to live solitary, purposeless lives. The question is whether her new life is ultimately better, however it feels.

The only way we can get Rose to ask that question is by asking her to think about the future, something Rose prefers not to do. Gently, we should insist that she must. We are not momentary creatures; we live 70 or 80 years. No sexual salvation is satisfactory from which the future must be excluded. Rose wants simply not to think at all, but to feel, and we would be dishonest if we tried to convince her that her new life does not feel better. For now, it feels better to her than she could have imagined. A Christian sexual ethic asks Rose to think not just of tonight, but of next week and next month and next year.

If she does, she will find her mind drawn to one terrible thought: Rose and Tom will probably break apart. People like Rose and Tom, without commitment to hold them together, usually do. Rose may find herself worse off: bereft, alone, “not good.” She will bear the imprint of someone she has lost. Of course, it is also certainly possible that Tom, or someone else, will stay with Rose, perhaps even eventually marry Rose. But how complete would their relationship be? The fullness of unitive love, which lasts forever and shares everything, is unlikely for those who willingly settle for something far less. Absolute and comprehensive commitment is not learned through “experimentation.”

Thus, George Gilder is right when he suggests a sexual version of Gresham’s law: As bad coins drive good coins out of circulation, so bad sex drives out good sex. So long as Rose engages in casual sex, she greatly reduces the chance that she can ever experience covenanted sex. Covenants are costly, and few people are far-seeing enough to pay the costs when the same tangible, immediate benefits are available for the rental price of a VCR movie. Not only is this so for Rose in particular, it operates for society in general. So long as there are Roses available, Toms will not be moved to think of commitments.

What is the best for Rose? What better hope can we offer her? We offer hope that she will awaken, not merely to her sexuality, but to the possibilities of Eden. That she will long, not merely for another date with another Tom, but for the unbreakable circle of naked delight that God created in the beginning. She is willing to gamble on the pleasures of today. We should raise the stakes: we should ask her to gamble on love “until death us do part.”

If we want to influence Rose this way, we had better do more than talk. We had better offer her, tangibly, another way out of her sexual desert. The many singles groups that have emerged in churches seem to be conscious attempts to do so. They provide single people with a place where they can, in a relatively unpressured environment, explore their own sexuality and that of other people.

I suspect sometimes pastors denigrate the “meet and be met” function of these singles groups, but it has a crucial purpose, especially if an effort is made to put sexuality into the larger context of Christ’s kingdom. Surely such a group would provide a better way for Rose to awaken to her sexuality.

The Church As Cupid

That better way, however, must not imply that singleness is inferior and that singles groups exist to arrange marriages. For a variety of reasons, some people simply will not marry. Christianity Today Institute dean Kenneth Kantzer points out the disproportionate number of young women in Christian congregations.

Many of these will not marry, if they insist on marrying Christians. Kantzer says, “To me it’s terribly important that an unmarried woman is not considered an incomplete person. She can be complete without a full expression of certain sexual aspects of herself because the essential part of her is her likeness to God. The same, of course, applies to unmarried men.”

Many people, however, would find it hard to imagine real fulfillment without genital sexuality. If marriage is impossible, should unmarried people grit their teeth and survive without sexual intercourse? If no one chooses to marry Rose, is celibacy the best we can offer her?

Paul thought celibacy was an undesirable state for some: “If they cannot control themselves, they should marry, for it is better to marry than to burn with passion” (1 Cor. 7:9). Christians have a stake in removing barriers to marriage, so that people can take this advice. When age (people either too young or too old), finances, or excessive idealism prevent people from seeing marriage as a realistic option, then some will undoubtedly be left simply to “burn with passion.”

Yet Paul’s perspective commends itself to us in another strange, difficult sense—strange at least for modern people, who value sexual intercourse so highly. He clearly says that celibacy is preferable to marriage. This option has never been embraced in Protestantism, and today ethicists sometimes dismiss it as the “Greek Paul,” who thought of the body as the source of evil for “spiritual” (nonmaterial) humanity, as opposed to the “Jewish Paul” who wrote Ephesians 5 and knew that body and spirit are undivided and that spiritual salvation is experienced in the flesh, in marriage, in sexuality.

This version of Paul is mistaken. Despite superficial similarities between his thought and some ascetic Greek philosophies, they are clearly worlds apart. Paul preached the incarnated Christ risen bodily from death; such a doctrine crowds out any possibility of a body-spirit dualism. Paul got his thoughts on celibacy from somewhere else.

It is not hard, really, to deduce where. He built on the pattern of Jesus, who spoke of God’s calling to celibacy (Matt. 19:12), whose disciples temporarily gave up wives and family to follow him (Luke 18:29), and who himself had neither wife nor children. Jesus taught that, however important marriage may be, it will not continue into heaven (Matt. 22:30). Must we also divide the Greek Jesus from the Jewish Jesus? It is more reasonable to recognize that when Jesus was born in Bethlehem, the old Jewish order, as well as the surrounding Greco-Roman culture, was radicalized. Something new had been born.

William Stafford refers to the “radical pattern” of celibacy, which Paul recommends to the Corinthian Christians. This was as significant in the early church as the more familiar pattern of marriage. The two patterns lived easily side by side within congregations until the full flowering of the monastic movement. After that, celibacy became the ideal for most Christians; at the Reformation this was reversed so that marriage became the ideal, and celibacy was viewed dimly. But must it always be one or the other? Can we never affirm both, as Paul evidently did?

Stafford points out that, in the early church, celibacy was practiced as part of a larger pattern of witness to the kingdom of God. Celibates typically lived communally, were nonviolent, and deliberately chose a simple life. Today there are Protestant communities that choose nonviolent, simple community life. They do so as a way of saying, “God is enough. We do not need power or money or property to transform our lives or the world.” Celibacy, as the church fathers practiced it, made a similar sexual statement: “God is enough.” His love filled their lives, and they were, in Paul’s words, “devoted to the Lord in both body and spirit,” living “in undivided devotion to the Lord” (1 Cor. 7:34–35). Of course, some of the early church fathers wrote against pleasure and even against women; their radicalism was not pure. Yet they never brought themselves to call marriage anything but good; they simply thought virginity, as it anticipated the heavenly kingdom, was better.

We have removed this biblical pattern from the church, and we are poorer for it. In the climate of our times it is difficult to imagine how it could again become attractive to someone like Rose. Yet must we always be embarrassed to recommend the pattern of life that our Lord, the apostle Paul, and nearly all of the church fathers followed? Surely Paul’s few words to the Corinthians suggest something better. Surely our singles groups need to apply themselves to the task of seeing celibacy again as a gift, as a positive witness to the world, whether for a short period or for an entire lifetime.

Involuntary Celibacy

There remains the question of those who do not choose to be celibate. They desire marriage and its sexual freedom, but they have not yet—and may never—marry.

Many Christians writing on sexuality have suggested that celibacy must always be freely chosen. For instance, Helmut Thielicke, writing to suggest tolerance of homosexual alliances, says that “Celibacy cannot be used as a counterargument, because celibacy is based upon a special calling and, moreover, is an act of free will.”

It is difficult to see the justification for this claim, as it relates to either the homosexual or the unmarried. If someone chooses celibacy as the best of undesired options, that is no different from many other moral situations. Surely we are often placed in situations where we find only one moral option. Our calling must then be to embrace that option.

In the same passage in which he recommends that virgins remain unmarried, Paul tells us that if you find yourself a slave, and cannot gain your freedom, you should be a good slave. If you are married (and in biblical times one might not have free choice in that), then you should live faithful, even to a pagan spouse. “Each one should retain the place in life that the Lord assigned to him and to which God has called him. This is the rule I lay down in all the churches. Was a man already circumcised when he was called? He should not become uncircumcised. Was a man uncircumcised when he was called? He should not be circumcised. Circumcision is nothing and uncircumcision is nothing. Keeping God’s commands is what counts” (1 Cor. 7:17–19).

Paul distinguishes between the situation in which a person finds himself by circumstance, and the calling of Christ. The calling does not usually change the situation; it transforms it into a Christian vocation. Not everyone who goes without sex is celibate in the sense that Paul would want him to be, for not everyone is entirely devoted to the Lord and answers Christ’s calling to him within that situation. But that people may hear that calling within their unmarried state, and that such a calling would be entirely good—indeed, the best of all options—Paul obviously does not doubt.

The question of those who cannot control themselves remains. So long as they burn with passion, how can they obey the call of Christ to live for him in their situation? This is an extremely difficult pastoral situation, and we owe compassion and patience to those who grapple with it. Yet it does not alter the fundamental ethical situation any more than the extreme difficulties of controlling alcoholism alters our judgment about drunkenness. We do not counsel alcoholics that—since they cannot stop drinking—they should proclaim alcoholism an ideal. We work doggedly in the hope they can break free—and many do, though they always remain aware of their vulnerability. So it is with those who burn with lust. We ought not to call their lust by another name. We ought to work, compassionately, to help them master it. We ought to bear in mind, as we persevere with them, that all human beings are enslaved to sin in some way, and that our salvation ultimately will be the Lord’s return. Sexual addicts are not different from the rest of us. We are all persistent and miserable sinners. Yet we will not always be so.

Ministry Of The Church

As we have noted, a Christian sexual ethic goes beyond the individual and private domain. It places sexuality in a larger framework, the body of Christ. The question arises, then: How does the church minister to the sexual needs of its culture?

Paul’s letters show he was not principally concerned that Christians critique their pagan neighbors’ sexual habits. He was chiefly concerned that Christians’ lives reflect the glory of the gospel. They would do this, he seemed to assume, as a community. His ethical reflections are rarely addressed to individuals. He was far more concerned with the life of the church as a whole. He wanted the church to be a counterculture—to show itself distinct from the surrounding culture. He expected Christians to strengthen and encourage one another to reflect the ultimate counterculture—the kingdom of God.

There is, in our time, no substitute for a ministry of sexual counterculture. People form their sense of sexuality in community—first in family, then more broadly through their interactions with a host of others. Yet we live in a world with very different sexual presuppositions from our own. If Christians are to gain a distinctively Christian sexual life, then they need the strength and encouragement of other Christians.

The visible witness of such a community will, in turn, do far more to convince our society than a million pamphlets on sex. Our rules we can explain, but rules are not necessarily attractive. Rules exist only to protect the sexual freedom of Eden. Those who see a community of sexual freedom will want to join it, and they will gladly submit to its rules. That is already happening, wherever Christians have managed to maintain strong, loving families. It should happen on a far wider front.

The church’s sexual ministry is first and foremost an inward ministry, which begins with teaching. We should not be instructing the world how to proceed with sex education if we cannot educate ourselves. Christians, in the face of rapid sexual changes, have been inarticulate. Not only have we often failed to convince those outside the church of the efficacy of a Christian sexual ethic, in many cases we have failed to convince ourselves and our children.

Sex education from a Christian perspective is not just for children; adults past the age of 90 keep thinking about, struggling with, and adjusting to their sexuality. The church, then, must become a place where adults can freely study sexuality, just as they would study biblical perspectives on faith or honesty. The growing popularity of sexual-advice columns and talk shows suggests the church has a mission to provide sex education to its adults.

However, we want particularly to teach our children. Every community’s vitality is tested by its ability to pass on fundamental values to the next generation.

In recent years Christians have emphasized, in opposition to secular schemes, that sex education should be done by parents in the home. In that framework, the fullness and complexity of sexuality is always potentially present. Children know their parents, and see them in every dimension of life. In contrast to the individualistic, competitive world of schools, homes should represent positive sexual values like marriage and community. The context in which a subject is taught does affect what substance is understood. And, of course, Christian parents can teach a Christian view that public schools cannot.