Sudden Family, Sudden Hope

Sudden Family, by Debi and Steve Standiford, Nhi and Hy Phan (Word, 1986, 163 pp.; $9.95, cloth). Reviewed by Roger P. Winter, director, United States Committee for Refugees.

Years ago, while at Wheaton College, I had the dream many young people have: saving the world from its ills. As I grew in experience, I learned the value and satisfaction of helping individuals. This is one of the lessons of Sudden Family.

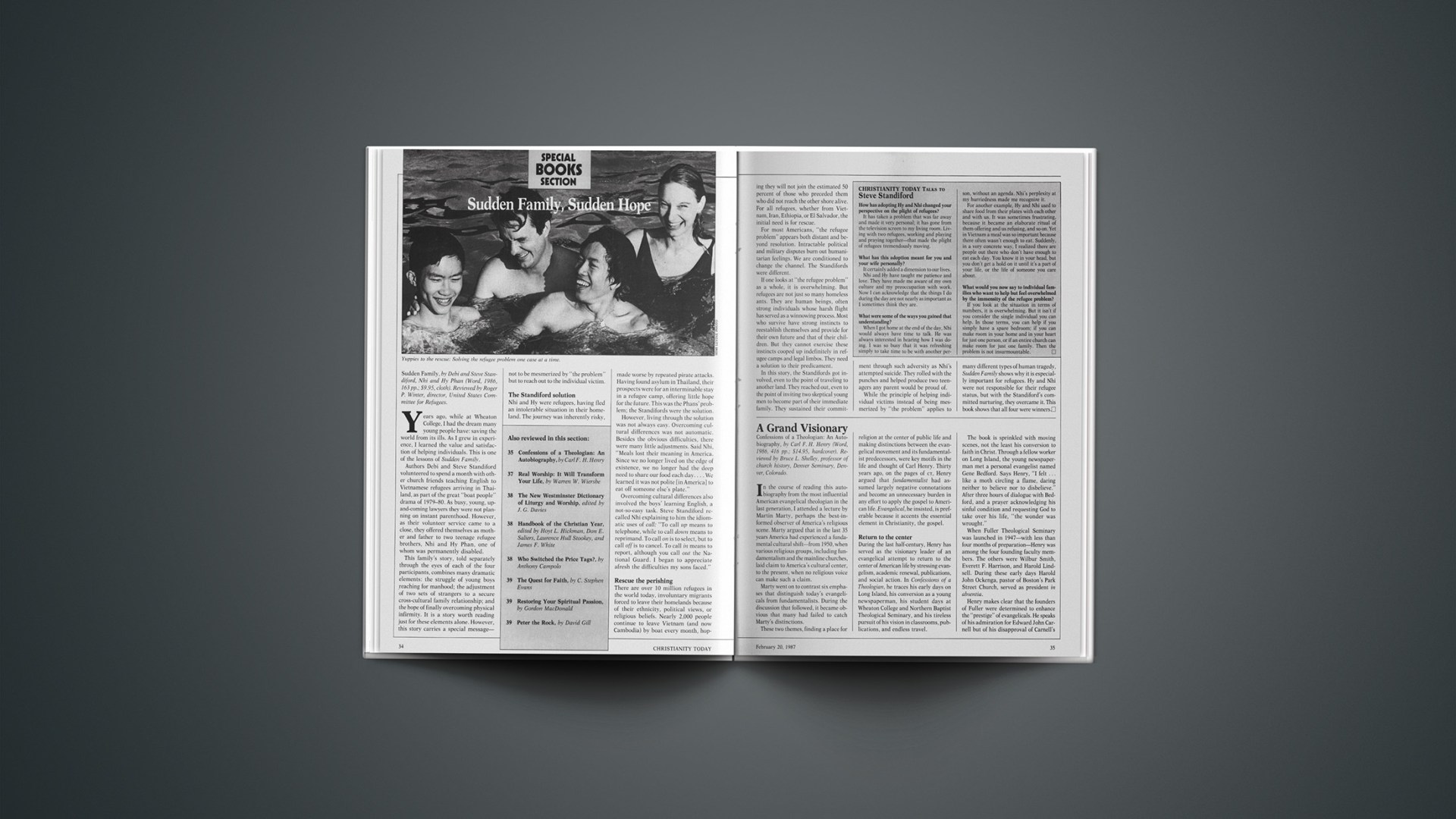

Authors Debi and Steve Standiford volunteered to spend a month with other church friends teaching English to Vietnamese refugees arriving in Thailand, as part of the great “boat people” drama of 1979–80. As busy, young, up-and-coming lawyers they were not planning on instant parenthood. However, as their volunteer service came to a close, they offered themselves as mother and father to two teenage refugee brothers, Nhi and Hy Phan, one of whom was permanently disabled.

This family’s story, told separately through the eyes of each of the four participants, combines many dramatic elements: the struggle of young boys reaching for manhood; the adjustment of two sets of strangers to a secure cross-cultural family relationship; and the hope of finally overcoming physical infirmity. It is a story worth reading just for these elements alone. However, this story carries a special message—not to be mesmerized by “the problem” but to reach out to the individual victim.

The Standiford Solution

Nhi and Hy were refugees, having fled an intolerable situation in their homeland. The journey was inherently risky, made worse by repeated pirate attacks. Having found asylum in Thailand, their prospects were for an interminable stay in a refugee camp, offering little hope for the future. This was the Phans’ problem; the Standifords were the solution.

However, living through the solution was not always easy. Overcoming cultural differences was not automatic. Besides the obvious difficulties, there were many little adjustments. Said Nhi, “Meals lost their meaning in America. Since we no longer lived on the edge of existence, we no longer had the deep need to share our food each day.… We learned it was not polite [in America] to eat off someone else’s plate.”

Overcoming cultural differences also involved the boys’ learning English, a not-so-easy task. Steve Standiford recalled Nhi explaining to him the idiomatic uses of call: “To call up means to telephone, while to call down means to reprimand. To call on is to select, but to call off is to cancel. To call in means to report, although you call out the National Guard. I began to appreciate afresh the difficulties my sons faced.”

Rescue The Perishing

There are over 10 million refugees in the world today, involuntary migrants forced to leave their homelands because of their ethnicity, political views, or religious beliefs. Nearly 2,000 people continue to leave Vietnam (and now Cambodia) by boat every month, hoping they will not join the estimated 50 percent of those who preceded them who did not reach the other shore alive. For all refugees, whether from Vietnam, Iran, Ethiopia, or El Salvador, the initial need is for rescue.

For most Americans, “the refugee problem” appears both distant and beyond resolution. Intractable political and military disputes burn out humanitarian feelings. We are conditioned to change the channel. The Standifords were different.

If one looks at “the refugee problem” as a whole, it is overwhelming. But refugees are not just so many homeless ants. They are human beings, often strong individuals whose harsh flight has served as a winnowing process. Most who survive have strong instincts to reestablish themselves and provide for their own future and that of their children. But they cannot exercise these instincts cooped up indefinitely in refugee camps and legal limbos. They need a solution to their predicament.

In this story, the Standifords got involved, even to the point of traveling to another land. They reached out, even to the point of inviting two skeptical young men to become part of their immediate family. They sustained their commitment through such adversity as Nhi’s attempted suicide. They rolled with the punches and helped produce two teenagers any parent would be proud of.

While the principle of helping individual victims instead of being mesmerized by “the problem” applies to many different types of human tragedy, Sudden Family shows why it is especially important for refugees. Hy and Nhi were not responsible for their refugee status, but with the Standiford’s committed nurturing, they overcame it. This book shows that all four were winners.

Christianity Today Talks To Steve Standiford

How has adopting Hy and Nhi changed your perspective on the plight of refugees?

It has taken a problem that was far away and made it very personal; it has gone from the television screen to my living room. Living with two refugees, working and playing and praying together—that made the plight of refugees tremendously moving.

What has this adoption meant for you and your wife personally?

It certainly added a dimension to our lives. Nhi and Hy have taught me patience and love. They have made me aware of my own culture and my preoccupation with work. Now I can acknowledge that the things I do during the day are not nearly as important as I sometimes think they are.

What were some of the ways you gained that understanding?

When I got home at the end of the day, Nhi would always have time to talk. He was always interested in hearing how I was doing. I was so busy that it was refreshing simply to take time to be with another person, without an agenda. Nhi’s perplexity at my hurriedness made me recognize it.

For another example, Hy and Nhi used to share food from their plates with each other and with us. It was sometimes frustrating, because it became an elaborate ritual of them offering and us refusing, and so on. Yet in Vietnam a meal was so important because there often wasn’t enough to eat. Suddenly, in a very concrete way, I realized there are people out there who don’t have enough to eat each day. You know it in your head, but you don’t get a hold on it until it’s a part of your life, or the life of someone you care about.

What would you now say to individual families who want to help but feel overwhelmed by the immensity of the refugee problem?

If you look at the situation in terms of numbers, it is overwhelming. But it isn’t if you consider the single individual you can help. In those terms, you can help if you simply have a spare bedroom; if you can make room in your home and in your heart for just one person, or if an entire church can make room for just one family. Then the problem is not insurmountable.

A Grand Visionary

Confessions of a Theologian: An Autobiography, by Carl F. H. Henry (Word, 1986, 416 pp.; $14.95, hardcover). Reviewed by Bruce L. Shelley, professor of church history, Denver Seminary, Denver, Colorado.

In the course of reading this autobiography from the most influential American evangelical theologian in the last generation, I attended a lecture by Martin Marty, perhaps the best-informed observer of America’s religious scene. Marty argued that in the last 35 years America had experienced a fundamental cultural shift—from 1950, when various religious groups, including fundamentalism and the mainline churches, laid claim to America’s cultural center, to the present, when no religious voice can make such a claim.

Marty went on to contrast six emphases that distinguish today’s evangelicals from fundamentalists. During the discussion that followed, it became obvious that many had failed to catch Marty’s distinctions.

These two themes, finding a place for religion at the center of public life and making distinctions between the evangelical movement and its fundamentalist predecessors, were key motifs in the life and thought of Carl Henry. Thirty years ago, on the pages of CT, Henry argued that fundamentalist had assumed largely negative connotations and become an unnecessary burden in any effort to apply the gospel to American life. Evangelical, he insisted, is preferable because it accents the essential element in Christianity, the gospel.

Return To The Center

During the last half-century, Henry has served as the visionary leader of an evangelical attempt to return to the center of American life by stressing evangelism, academic renewal, publications, and social action. In Confessions of a Theologian, he traces his early days on Long Island, his conversion as a young newspaperman, his student days at Wheaton College and Northern Baptist Theological Seminary, and his tireless pursuit of his vision in classrooms, publications, and endless travel.

The book is sprinkled with moving scenes, not the least his conversion to faith in Christ. Through a fellow worker on Long Island, the young newspaperman met a personal evangelist named Gene Bedford. Says Henry, “I felt … like a moth circling a flame, daring neither to believe nor to disbelieve.” After three hours of dialogue with Bedford, and a prayer acknowledging his sinful condition and requesting God to take over his life, “the wonder was wrought.”

When Fuller Theological Seminary was launched in 1947—with less than four months of preparation—Henry was among the four founding faculty members. The others were Wilbur Smith, Everett F. Harrison, and Harold Lind-sell. During these early days Harold John Ockenga, pastor of Boston’s Park Street Church, served as president in absentia.

Henry makes clear that the founders of Fuller were determined to enhance the “prestige” of evangelicals. He speaks of his admiration for Edward John Carnell but of his disapproval of Carnell’s move to the presidency, succeeding Ockenga in 1954. He reports that the school lacked cohesiveness (“Everyone was engaged on personal projects”), and that after his departure in 1956, the school shifted its position on the inerrancy of the Scriptures.

In 1956 Henry left Fuller to assume duties as editor of CT, a post he held for the magazine’s first 12 years. He contends that the magazine was “from the outset committed to biblical inerrancy as a matter of doctrinal consistency, but it nonetheless enlisted as allies all scholars who fought well on implicit biblical grounds for the great articles of faith.”

Henry takes no fewer than five full chapters to tell his experiences with the magazine. He reveals that differences over the targeted readership of the magazine and over board influence upon editorial policy led to his departure in 1968. Later, the board told Henry his leaving was due to “a sad and colossal misunderstanding.”

In 1973 Henry became lecturer-at-large for World Vision International. The huge relief organization covered his travel costs and paid him a “modest stipend.” This enabled him to minister to Third World churchmen and to continue, and complete, his major writing project, the six-volume God, Revelation and Authority.

Obviously not all who lived through the early days of Fuller seminary and CT will agree with Henry’s interpretation of the events. Interpersonal relationships are always subject to a variety of readings. Historians, however, will find this autobiography a valuable resource for tracing the story of these institutions.

Forfeited Opportunities

At 73, Henry still maintains two fundamental convictions: American evangelicals presently face their greatest opportunity since the Protestant Reformation, but they are forfeiting the opportunity stage by stage. Too many of them are basking in the glow of large numbers rather than challenging American values by issuing a clear call to repentance, rededication, and renewal.

Carl Henry is, and since his Christian conversion has always been, a visionary. In his own reminiscences, Henry confesses, “Fifty years ago I had, as a young Christian, grand visions of the world impact of evangelical Christianity; today, as a timeworn believer, I still dream at times [but] … it is difficult … to distinguish dreams from hallucinations.”

Those “grand visions” bring us back to Martin Marty’s observations. What if, contrary to Henry’s dreams, there is no center in American life for evangelicals to occupy? What if the best we can hope for is one place in the American sun alongside many others?

Journey Of The Heart

Real Worship: It Will Transform Your Life, by Warren W. Wiersbe (Nelson, 1986, 191 pp.; $12.95, cloth). Reviewed by Calvin Miller, pastor of Westside Church, Omaha, Nebraska, and author of Fred ‘n’ Erma (InterVarsity Press, 1986).

“In worship we declare what I is really valuable to us,” says Warren Wiersbe, veteran pastor and general director of Back to the Bible Broadcast. Convinced he is right, my mind devoured Wiersbe’s new book. But I soon found that Real Worship is more a journey of the heart than the mind.

Wiersbe avers that we do not worship God because of what God does for us, but because of who God is to us. The impact of this truth is profound. Often as I read these pages, I forgot this was a book about worship and became lost in the act of worship. Christ was defined in the volume as the object of worship, but he loomed so large that he transcended definition and I cried, “Halleluiah!” (which, by coincidence, is the title Wiersbe initially selected for this book).

“Wonder, witness and warfare,” says Warren Wendell Wiersbe, “is the world of worship.” But in spite of all these W-words, you won’t see this book as an old evangelistic sermon with three alliterative points and a poem. Wiersbe’s outline moves out of the way after it organizes the book. And a solid and scholarly challenge threads substance through the piece. Still, all great truths ever stop the mind, and turn it from academics to praise. The prayers in this book are simple and yet seem the very heart of what must be said to God.

Wiersbe wakes us to the wonder of God. He says early in the book that the goal of worship is “Christlikeness in character.” He calls us to leave the shallowness of some gospel media super-stars, beckons us around the sterility of corporate church organizational issues, and points us to the altar of union with Christ. He helps us see that merely cosmetic changes in public worship rarely affect the heart. And at last, we come to see that worship is to be a blessing as much as to receive one.

Real Worship does better at inspiring great worship than describing it. Not that suggestions, examples, models are left out of the book, but much of the work of applying it belongs to the reader. If you are looking for a manual on worship, look somewhere else. Wiersbe calls us to the “when and why” of worship, not the “how to.”

As I finished the book, one phrase haunted me and drove me into close fellowship with Christ. It was a longing expressed by the author himself: “Whatever it is that I must burn—here are the ashes.” In such an author lies a need for grace that leaves us all with a blessed hunger for God. Such hunger feeds on worship and calls us to the meal.

Renewal Resources

The New Westminster Dictionary of Liturgy and Worship, edited by J. G. Davies (Westminster, 1986, 560 pp.; $29.95, cloth) and Handbook of the Christian Year, edited by Hoyt L. Hickman, Don E. Saliers, Laurence Hull Stookey, and James F. White (Abingdon, 1986, 304 pp.; $15.95, paper). Reviewed by Robert Webber, professor of theology, Wheaton College, and author of Celebrating Our Faith.

The renewal of Christian worship that began several decades ago in the Catholic church is now spreading into the mainline Protestant and evangelical churches. This has created a crisis of sorts: pastors need resources to guide worship reform and renewal. And these two books are just that—resources.

The New Westminster Dictionary of Liturgy and Worship is an update of an older work published in 1979. It contains more than 70 new articles as well as an update of other articles. Pastors and students will particularly appreciate the in-depth studies of different worship models, explanations of terminology, and insights on the use of the arts in worship—music, drama, dance, and the electronic media.

The article on Baptist worship is a good example. Baptist worship scholar John E. Skoglund defines worship as “celebration of the gospel,” and places this view of worship squarely in Baptist ecclesiology. Skoglund then traces Baptist worship historically from the leadership of John Smyth through the influences of the free worship of Presbyterian and Congregational churches into the various worship patterns of modern Baptists. The article continues with an evaluation of cultural influences on Baptist worship, and concludes with a discussion of the Baptist view and practice of the Lord’s Supper. Like other articles in the book, this one makes a sympathetic attempt to understand Baptist worship in its cultural context without biased criticism or unthinking claims to superiority.

The Handbook of the Christian Year provides valuable insight into the meaning of Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Holy Week, Easter, and Pentecost. It also offers sample services for each season. Although the four contributors to this volume are Methodists, they call for the recovery of the universal tradition of worship that is faithful to the biblical and historical tradition.

Church leaders concerned for worship renewal will do themselves a favor by reading and using both books. They put us in touch with the tradition and describe what is happening in the universal church. And consequently, they not only make the best resources available, but prevent us from assuming that worship renewal consists of rearranging the chairs, playing a guitar, and singing spirituals.

Learning How To Have Fun

Who Switched the Price Tags? by Anthony Campolo (Word, 1986, 200 pp.; $11.95, cloth).

Tony Campolo wants us to have fun. But, he says, “Learning how to have fun is one of the most serious subjects in the world.” So he has written a book that explores four aspects of this theme: values, jobs, families, and churches. Fun comes from knowing what is really important in life (values). With that settled, Campolo tackles work, love, and worship/service.

In the first section of the book, this Eastern College sociologist seeks to clarify values for young people. Citing a Fortune survey of 25-year-olds (who believe in financial success, in themselves, and in the corporate world; shun family ties and personal loyalty; and remain skeptical about learning from older leaders), he proceeds to reflect on the value of relationships and the self in the light of God’s grace and glory. This is the heart of the matter if one wants to critique the success-oriented yuppie lifestyle. Persons matter over property, power, and pride.

Campolo’s discussion of the working world, marriage and family, and the church proceeds with panache, backed up by solid sociological research and biblical study. Campolo is skilled at challenging our cherished priorities. Some of us are too comfortable with our finally gained affluence, just as the young are too eager to follow our lead. We need his help in resetting or reinforcing biblical priorities.

Campolo’s book could be better: His treatment of Calvinism’s contribution to the work ethic could have been more nuanced. A secularized strain (not the Calvinistic value system as a whole) led to contemporary wealth and health gospels. Reliance on Reformed scholar Bob Goudswaard’s studies in economic history would have sharpened and enriched his presentation.

But all in all, Who Switched the Price Tags? is a very helpful book, written with sophistication for an audience that loves style and yearns for substance. Share it with your favorite young urban professionals. Or if they don’t read, show them Campolo’s films by the same name.

Food For Thought

The Quest for Faith, by C. Stephen Evans (InterVarsity, 1986, 143pp.; $4.95, paper).

Why do some people believe while others don’t? Why do people change beliefs? What do you need to consider if you are on the verge of belief? These questions have occupied Stephen Evans during the last 15 years and through several books on philosophy and apologetics.

Quest for Faith discusses the question of commitment in simple, clear terms. Listening to Evans (who teaches philosophy at St. Olaf College) is like visiting your prof in his office. You pose problems. He says, “Yes, but look at it this way.” He asks, “Doesn’t it seem plausible?…,” and you go away with food for thought.

Evans points out that the existence of God is indicated by mysteries as well as by evidence. Mysteries found in the universe, in the moral order, and in persons provide clues about God. Evans uses these as a bridge across the resistance of atheism and agnosticism. Later chapters explore the deity of Jesus, miracles, the Bible, the problem of evil, and religion as a crutch. The final chapters outline the good news and urge commitment to Jesus.

The simple clarity of this book—both writing and argument flow easily without loss of substance—suggests it should be used in dialogue with thoughtful non-Christians or as reading matter for a new Christian who wants to be ready with answers at the office or on the campus.

Taking The Cure

Restoring Your Spiritual Passion, by Gordon MacDonald (Nelson, 1986, 223pp.; $12.95, cloth).

If you once had it and have now lost it (but you want it back), Gordon MacDonald offers some hints as to why you went into mothballs and how you can be reactivated. Spiritual passion and intensity can be drained by intensive ministry (Elijah), dried out by lack of spiritual food (David), distorted by the world (Lot), devastated by opposition (Paul), disillusioned by the situation (Moses), defeated by your own failure (Peter), and disheartened by threats (Ahaz).

Faced with this list, what can you do? MacDonald, who is president of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, outlines several resources for restoration—people (who stimulate us to new life and test us at the same time), places (of sanctuary, quiet, protection, and strength), principles (Sabbath rhythms, rememberings, recurrences, renunciations, and rests), and partners (sponsors, rebukers, affirmers, intercessors, and pastors).

This is a well-written, tested handbook for the veteran Christian. Beneath the smooth phrase and apt illustration lies the firm muscle of a seasoned pastor. If you haven’t lost it yet, this is preventative medicine. If you’re whipped, it’s a cure.

Through Peter’S Eyes

Peter the Rock, by David W. Gill (InterVarsity, 1986, 206pp.; $6.95, paper).

When we see Christianity through the eyes of the apostle Peter, we can know our guide rather fully. The New Testament includes biographical detail (conversion, early discipleship, later leadership in the church) and two of his letters (which let us explore his head a bit). The close fit between these two sources enables David Gill, dean of New College, Berkeley, to frame a series of lessons for us in evangelism, conversion, discipleship, apologetics, and the church.

Gill chose Peter as the lens for exploring the meaning of Christianity because he is so ordinary—unlike Paul, for instance, who seems heroic and distant to many. Gill’s method is to study Peter in a roughly chronological manner, using themes such as conversion, discipleship (basics, failures, recoveries), leadership, and ministry. He explores historical passages first and then traces the same themes in Peter’s letters. An integrated portrait of his life and thought emerges.

Although the footnotes give evidence of thorough scholarship, the book is written for the inquiring lay person. Discussion questions at the end of each chapter will aid use by study groups.

Book briefs by Larry Sibley, who teaches practical theology at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia and is director of public relations there. From 1981–86 Sibley was book editor for the Bible Newsletter.