The familiar caricature of Calvin’s theology is symbolized by the mnenomic device TULIP: Total depravity, Unconditional election, Limited atonement, Irresistible grace, and Perseverance of the saints. These so called “five points of Calvinism” arose in the seventeenth century, amid great political and theological turmoil in the Netherlands.

In the early seventeenth century, Jacob Arminius, professor of theology at the University of Leiden, came under suspicion by the more orthodox Dutch Calvinists. Arminius was viewed to have seriously deviated from the orthodox doctrines of justification and election. Charges of Pelagianism were made, and the matter quickly escalated.

In retrospect, Arminius’ views were not, strictly speaking, Pelagian. He did, however, differ from Calvinist orthodoxy on a number of issues. He denied the doctrine of perserverance and questioned whether grace was necessary for one to come to faith. He also challenged the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. The desire of Arminius was to uphold the goodness and mercy of God. He was concerned that Calvinist doctrines made God the author of sin and wanted to stress the importance of faith and holiness in the Christian life.

His untimely death provided only a temporary reprieve. The fires were soon rekindled by his followers. Under the leadership of John Uytenbogaert, the Arminians met in 1610 to draw up what was called a remonstrance. It was simply a petition for toleration and a summation of their views in five points. They modified the doctrine of unconditional election, asserting that God did not elect individuals. They argued that God’s election was more general and had reference to that group of men who exercised faith. Like Arminius, they also denied perseverance of the saints, saying God’s gift of faith could be resisted by man. Finally, the Arminians affirmed that Christ died for the sins of every man.

The orthodox Calvinists responded with a seven-point statement called the counter-remonstrance. The government tried to settle the controversy with a series of ecclesiastical conferences. But matters only grew worse. Riots actually broke out in some areas of the Netherlands. Finally, amid a battle between political rivals, Prince Maurice and Oldenbarnveldt, a national synod was called to settle the controversy.

The synod convened in 1618 in the Dutch city of Dordrecht [Dort]. To insure fairness, the Dutch Calvinists invited delegations from Reformed churches throughout Europe. Simon Episcopius represented the Arminian position at Dort. The rejection of Arminian theology was unanimous. Five theological points were formulated to answer the Remonstrants. The Canons of Dort declared that fallen man was totally unable to save himself [Total Depravity]; God’s electing purpose was not conditioned by anything in man [Unconditional Election]; Christ’s atoning death was sufficient to save all men, but efficient only for the elect [Limited Atonement]; the gift of faith, sovereignly given by God’s Holy Spirit, cannot be resisted by the elect [Irresistible Grace]; and that those who are regenerated and justified will persevere in the faith [Perseverance of the Saints].

These doctrines have been called the five points of Calvinism and are often symbolized by the well-known “TULIP.” However, they are not a full exposition of Calvin’s theology. To be sure, these doctrines do reflect Calvin’s viewpoint in the area of soteriology. For example, the synod of Dort does not address Calvin’s devout commitment to Scripture, nor does it say anything about the Trinity or Christ. The doctrines of Dort are more properly viewed in their historical context as a theological response to the challenges of seventeenth-century Arminianism.

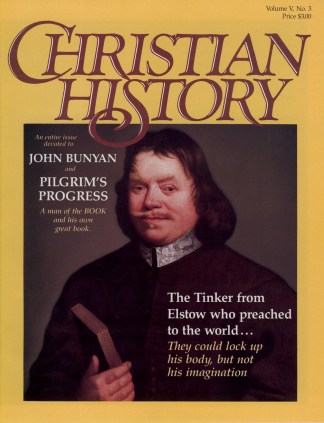

Copyright © 1986 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.