At a high school in Israel, Arab students gather discarded pieces of colored tile and arrange them into mosaics depicting Bible themes. The mosaics, now decorating a wall below the school library, depict the prophet Elijah being fed by a raven; Christ’s miracle of the loaves and fishes; and the word peace in Arabic, Hebrew, and English.

The fragments of information Western evangelicals use to construct an image of Arabs probably would not form a picture of a student art project with biblical themes. Instead, bits of headlines and news reports form for us a mental mosaic of terrorists, fanatic disciples of Islam, or oil-rich sheiks.

Though concerned with Christian brethren everywhere, evangelicals often forget there is a significant community of Arab Christians within Israel and its occupied territories. They are Greek Orthodox, Catholics, Melkites, and Protestants, together making up less than 10 percent of the Arab population there. Arab Christians trace their spiritual roots back 2,000 years to the time the early church began witnessing to the Gentiles, and they are proud of their long heritage. As a church official in Jerusalem points out, “We know Saint Paul went to Arabia in preparation for his missionary journeys to Europe. So Arabia got the news of Jesus Christ well before Europe did.”

Arabs who are Christians do not all agree on a single approach to the political dilemmas of the Middle East, and they differ in the ways they relate to Jews and to Christians outside their own tradition. Yet there are several common threads that draw them together. They call themselves Palestinians—a term of national identity that is considered invalid by many Israelis. They have a special affinity for Christ’s teachings, particularly his Sermon on the Mount; and they liken their own circumstances to Christ’s ordeal as refugee, outcast, and martyr.

Arab Christians do not disassociate themselves from their Muslim friends and neighbors. They exhibit the same characteristic samed (steadfastness) other Palestinians have developed through three generations of waiting for their social and political status to be resolved. And most of them believe peace is possible if attitudes change on the part of both Jews and Arabs.

The Christian Arab population of Israel is dwindling, as families move away in search of personal security and better opportunities for education and work. Before the State of Israel was established in 1948, there were between 25,000 and 40,000 Christian Arabs in Jerusalem. Now there are fewer than 9,000. In total, there are between 100,000 and 120,000 Arab Christians in Israel and the territories it controls. (These include the West Bank, or Judea and Samaria; the Golan Heights near Syria; and the Gaza Strip near Egypt.)

The steady hemorrhage of Christians from the Arab community has demoralized church leaders there, and it raises a serious question about attitudes of Christians in the West toward these believers. A Melkite priest in Galilee, Father Elias Chacour, said in frustration, “If things happen in Galilee as they did in Ramallah and Jerusalem, where there is almost no Christian community now, why would American Christians come here? To visit the ruins of Christianity? Would you like to follow the footsteps of the Lord without any Christian community here?”

U.S. evangelicals may inadvertently hasten the dismemberment of the Arab Christian community by offering uncritical moral and political support to the State of Israel. Most Christians in Israel, both Arab and Hebrew, accept the evangelical attentiveness to prophecy and empathy with the Jewish construction of a homeland. Few Christians in Israel dispute the existence of the State of Israel. At the same time, they emphasize that American evangelicals must not lose sight of the biblical imperative of justice and compassion for all peoples. Victor Smadja, a leading Hebrew Christian layman in Israel, said, “Jewish believers are very faithful to Israel but not at the expense of being faithful to Christ. The Gentiles make an error in thinking that because of the past, they have to be pro-Israeli. That is sentimentalism, not a healthy Christian attitude.”

Palestinians in Jerusalem and within the pre-1967 borders of the State of Israel can become Israeli citizens, hold jobs, and vote—although Israel’s electoral process of direct proportional representation by party virtually excludes Arabs from being elected to the Knesset. Jerusalem, like Mayor Daley’s Chicago, is a city that works despite its fractious elements. It was a divided city, with the Arab half under Jordanian control, until it was unified under Israeli rule after the Six-Day War of 1967.

On the occupied West Bank of the Jordan River, and on the Gaza Strip, more than one million Arabs live in towns like Bethlehem and Ramallah. About 60,000 of them are in refugee camps run by the United Nations. Many were displaced from their villages in 1948, and have seen their children and grandchildren grow up with no promise of returning to towns they still consider “home.” Until 1967, they, too, were governed by Jordan in the West Bank or by Egypt in Gaza.

The Six-Day War brought the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem residents under Israeli military rule and into an intractable stalemate. Here Israel faces an excruciating dilemma. It believes Judea and Samaria are God-given lands, and that it needs the West Bank as a military buffer zone. Yet if the West Bank were annexed and its people given full political rights, the Israeli Jews could eventually be outnumbered and the State of Israel would be vulnerable. The present status of military occupation embitters Arab residents and leads, over and over, to violence. The clash of two nationalities claiming the same land is the essence of the “Palestinian problem” that stands in the way of progress toward peace.

Elsewhere, in the pastoral villages of the Galilee, tension between Palestinians and Israeli authorities is more a contest of matching wits and will. The officials are more distant, so Arabs in rural Israel exercise a greater measure of control over their lives and have a degree of self-confidence that is missing in the communities under occupation.

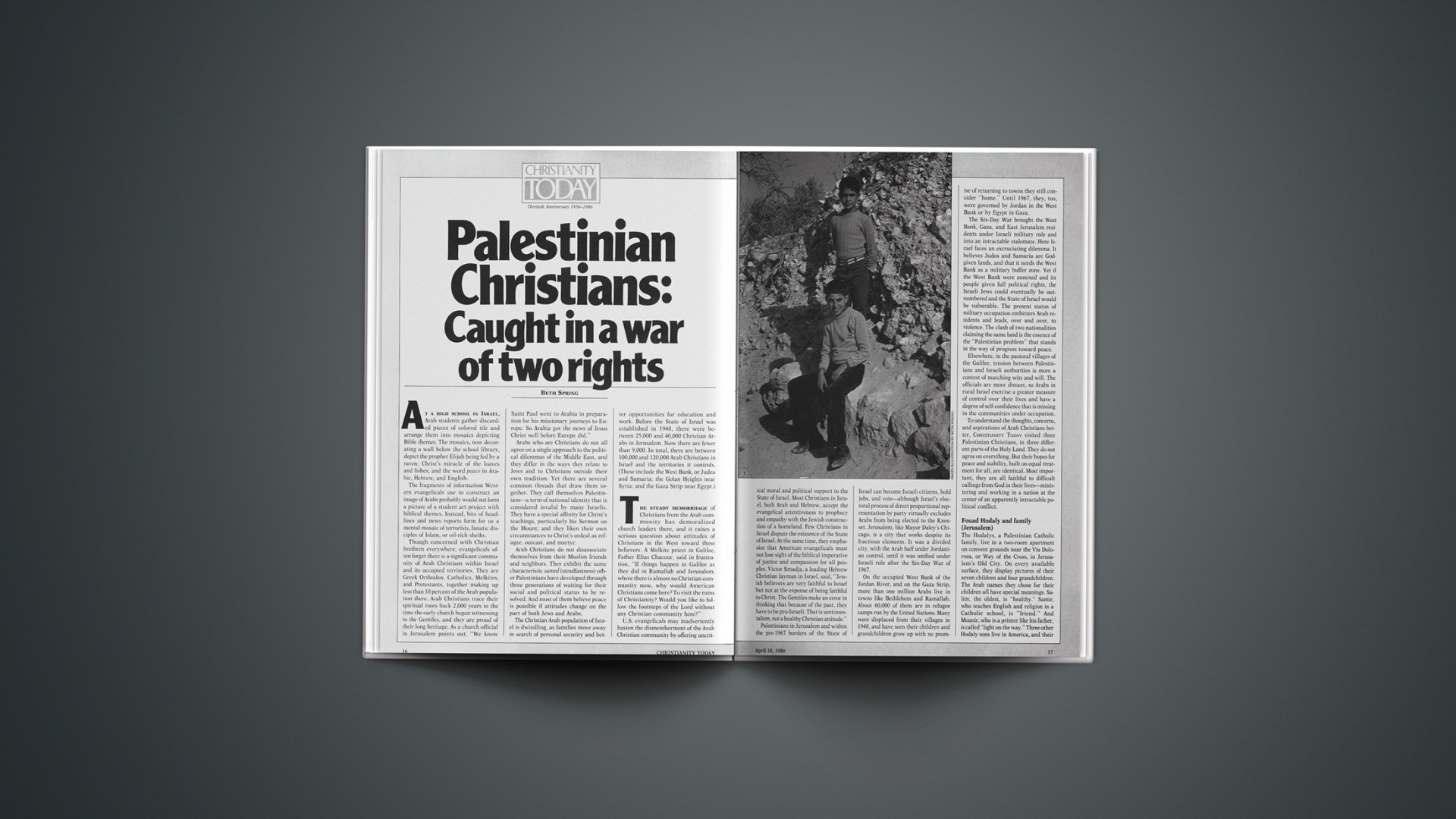

To understand the thoughts, concerns, and aspirations of Arab Christians better, CHRISTIANITY TODAY visited three Palestinian Christians, in three different parts of the Holy Land. They do not agree on everything. But their hopes for peace and stability, built on equal treatment for all, are identical. Most important, they are all faithful to difficult callings from God in their lives—ministering and working in a nation at the center of an apparently intractable political conflict.

Fouad Hodaly And Family (Jerusalem)

The Hodalys, a Palestinian Catholic family, live in a two-room apartment on convent grounds near the Via Dolorosa, or Way of the Cross, in Jerusalem’s Old City. On every available surface, they display pictures of their seven children and four grandchildren. The Arab names they chose for their children all have special meanings. Salim, the oldest, is “healthy.” Samir, who teaches English and religion in a Catholic school, is “friend.” And Mounir, who is a printer like his father, is called “light on the way.” Three other Hodaly sons live in America, and their daughter is in Peru.

Mounir carries a black-and-white photograph of himself as a baby, surrounded by his brothers; Fouad, the father, shows off a picture of his parents with all their grandchildren. It goes without saying that two things matter very much to Palestinian parents: preserving family ties and guaranteeing their children the best educational and employment opportunities possible. Yet, as the Hodalys have discovered, if a family satisfies its goal of providing opportunity for a son or daughter, its desire to stay together is frequently thwarted.

Fouad Hodaly, dressed in khaki work clothes, deliberated over the politics of Palestine. He pointed out that among the Israelis, there are Arab Jews as well as European Jews, so racial differences are not insurmountable. He believes the Israeli government sincerely wants peace, and the process of achieving it requires, most of all, just getting used to one another over time. Eventually, he said, the sort of coexistence that works in Jerusalem could permeate the whole nation.

He believes history is a progression of events of which God is in charge. Looking up verses in a leather-bound Arabic Bible, Fouad referred to Matthew 13. No one except the Lord can separate the “wheat” from the “tares” growing side by side in the confines of Israel and its disputed territories, he said. Arabs and Jews alike harbor both elements in their midst. Fouad observed that the Roman Catholic feast of Christ the King was approaching. “I pray that Christ will rule as king in all our hearts.”

Fouad’s son Mounir is considerably more fatalistic about the future course of events in the Middle East. “It is like a ball on a soccer field,” he said. “It could go this way or that way.” In any event, the Palestinians’ perspective is that of a nonparticipant. They feel sidelined, as forces far greater than they—especially the United States—play a decisive role in Middle East politics.

Like other Palestinians in Jerusalem, the Hodalys experience day-to-day annoyances. They would like to spend Christmas Day in Bethlehem, Fouad said, but they would need a special permit to go there. After a child threw a stone at an Israeli army vehicle by an Old City gate, Salim, the oldest son, was taken to a police station for questioning along with all the other Arabs working and shopping nearby.

Following dinner at home one evening, Salim drove two American visitors to their hotel via the Mount of Olives, stopping to show them Jerusalem by night. An Israeli military jeep pulled up by Salim’s door and a soldier stepped out. Holding his automatic rifle by its barrel, pointed skyward, the soldier peered into Salim’s window and began interrogating him in Hebrew.

“Who are you? Where do you live? Why are you here? Who are these people? Where are they staying? Are they tourists?” Salim answered softly and politely. He told the soldier his guests would return to their hotel in Jerusalem shortly.

The Hodalys are friends of an American evangelical missionary, Rick Van de Water, who came to Israel in 1974. Van de Water emphasizes that many Arab Christians abandon their faith as they face daily pressures. Others have emigrated to the United States, telling Van de Water, “I could not feel at peace in my own home.” Without what he calls a “real, living faith,” Arab Christians are “vulnerable to becoming atheists and Communists.” Even fringe groups that advocate terrorism fill a need for purpose in their lives.

Van de Water’s ministry is dedicated to presenting the gospel as the only alternative to a life of frustration and despair. For families like the Hodalys, that alternative has made a difference.

Bishara Awad (The West Bank)

Bishara Awad, a resident of Bethlehem on the occupied West Bank, is founder and president of Bethlehem Bible College, a training school for Christian young people. Throughout his adolescence and college years, Awad struggled with the full range of emotions Van de Water identified. When war broke out in 1948, Awad was seven years old. His family lived in a neighborhood in Jerusalem that was taken and forcibly evacuated by Israeli soldiers. Etched on Awad’s memory is a gruesome scene he saw played out in his front yard.

Awad’s father stepped out of the house to greet what he thought was a group of friendly soldiers. Without warning, he was shot in his front yard. Awad’s mother dragged him inside, and later buried him behind the house. Awad believes the soldiers were Israelis, but he admits there is no proof. Awad’s family was driven from its home a short time later as the Israelis occupied part of Jerusalem. Awad’s mother kept the family together, sending her seven sons and daughters to an orphanage school while she worked and went to school to learn nursing.

The Awads are Protestant evangelicals, active in a missionary Church of God on the Mount of Olives. When Bishara graduated from high school, he came to the U.S. to attend Dakota Wesleyan College in Mitchell, South Dakota. The events of his childhood continued to haunt him. “You cannot take away your childhood hatred and the memory of the thing that caused you to live without a father all your years,” he said.

When war broke out in 1967, Awad was in Kansas City. He was told he could not come home, except as a visitor. He obtained a temporary visa, and returned to visit his homeland, hoping—somehow—to stay there permanently. He met and married a woman from Gaza, who filed reunion papers for him saying he was a foreigner. His papers were accepted; he was allowed to stay.

He became principal of Hope School in Beit-Jala, founded by the Mennonite Central Committee for junior high and high school orphan boys. That is where his faith in Jesus Christ was reaffirmed, as he poured his energies into shaping young Palestinian lives. “The Lord worked in my life so I could get over this hatred, because I knew the Lord would not use me as long as I had all this hatred.”

Awad realized that there is little opportunity for Arab Christian young people to pursue theological training, and that those who do pursue training enroll in seminaries overseas, often never returning home. In 1979, assisted by two Americans, he began organizing Bethlehem Bible College.

The school, located three blocks from Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity, offers a three-year program in Bible, Christian education, and music. It has enabled local Arab Christians to move into leadership positions in their churches.

Awad teaches a class on the four Gospels, called “Life and Teachings of Jesus.” He uses Scripture to counsel young men and women who are still ensnared by the hatred he knew as a college student. “They read it for themselves in the Bible—that they are to live the Sermon on the Mount and listen to the authorities. It is extremely difficult, but Jesus lived under the same circumstances that we live under now.”

Circumstances on the West Bank, more than anywhere else in the region, cause Palestinians to say they feel like nonpersons. They drive cars with blue license plates that set them apart from Israeli citizens with yellow plates. At government security checkpoints, Arab drivers are routinely pulled over for questioning.

Heavy-handedness on the part of young, eager Israeli soldiers especially rankles West Bank Arabs. Petty violations, such as a child throwing a stone at an army vehicle, may be cause for an entire school to be shut down or a sudden curfew imposed. Palestinians joke bitterly about it, saying the Israeli army has a plan to disarm Arabs by clearing the West Bank of stones. Nonetheless, putting into practice some of Christ’s “hard sayings” is a daily event at the Bible college.

Awad is also involved in a new initiative to arrange meetings between Arab and Jewish Christians. Some 150 believers were invited to Jerusalem Baptist House for an unprecedented time of fellowship and worship in March, as a result of smaller meetings that have been going on for at least two years.

Award described his experience at the meetings: “The first time you meet with Jewish believers they are still your enemy, but the Lord told us to love our enemies. You can see the tension on both sides, but after several meetings, slowly, you just accept each other and love each other. Both sides have wanted to get together, and it has been eyeopening for both. To have a brother who is Jewish being loved by an Arab—I think this is history in itself.”

Awad’s warm acceptance of Jewish believers stands in sharp contrast to his opinion of Western Christians who support the Israeli government and at the same time neglect the indigenous community of believers there. Christians from abroad who are raising money to rebuild the Jewish Temple of Solomon, on top of a Muslim holy site, are terribly misguided, Awad said. They have no idea what their scheme would mean for the Christian community there: “It would be a catastrophe. The first people who would be killed in a civil war are the Christians—the local people—because Muslim journals report that Christians are initiating this.”

Last year, Awad visited Minnesota, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C., to raise support for Bethlehem Bible College. As he interacted with evangelicals, he said, “Many were surprised that I am an Arab and a Palestinian. I know I was not welcomed as if I were a Jewish believer or even a Jew who is not a believer.” Awad adds, “I think the church should awaken to the fact that Christ died for all people, regardless of who they are.”

Possessing the Land

A chronology of events in the dispute over Palestine.

63 B.C.–A.D. 73 Palestine ruled by Rome. Jerusalem is destroyed, the second Temple of Solomon demolished. Jews driven into exile throughout the Roman Empire become known as the Diaspora.

A.D.622–637 Islam established. On the ruins of Solomon’s temple, the Mosque of Al-Aqsa and the Dome of the Rock are built.

1100–1250 Crusaders conquer Holy Land. 1400s–1918 Ottoman Turks rule Middle East. 1881 Pogroms in Russia force millions of Jews to move west.

1897 First Zionist Congress, led by Theodor Herzl, meets in Basel, Switzerland; designates Palestine as Jewish homeland. Population of Palestine is less than 10 percent Jewish.

1917 World War I. British Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour promises the World Zionist Organization that Britain supports a homeland in Palestine for the Jews. Arabs are promised autonomous national governments.

1920–48 Britain rules Palestine under an agreement with the League of Nations. Palestine Mandate authorizes World Zionist Organization to organize massive immigration of Jews.

1939–45 World War II. Six million Jews murdered in Holocaust. Jewish population in Palestine increases from 56,000 in 1918 to 445,000 in 1939 to 608,000 in 1946.

1947 Britain turns problem over to United Nations. UN recommends partition of Palestine into two states, Arab and Jewish. Arabs refuse to accept partition.

1948 Israel declares independence. Arab armies enter Palestine. Israel defeats them and seizes all of Palestine. Of the 1.3 million Palestinian Arabs, 726,000 become refugees.

1967 Six-Day War. Israelis crush Arab armies, taking Sinai, Golan Heights, and West Bank; 750,000 refugees flee Israel. Jordan becomes site of Palestinian guerrilla action.

1970–71 Palestinians try to overthrow King Hussein of Jordan. They are defeated and move to Lebanon.

1973 Yom Kippur War begins. Israelis are pushed back in Sinai.

1974–75 Shuttle diplomacy by Henry Kissinger results in some Israeli pullbacks from territory it won in 1967.

1977 Egyptian President Anwar Sadat visits Israel, recognizes Israel as a state, and begins negotiating a peace treaty.

1978 Camp David accords are signed by Sadat, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, and U.S. President Jimmy Carter.

1982 Israel invades Lebanon, routs Palestinian Liberation Organization armies.

1985 Israel pulls out of Lebanon. Radical anti-Zionist groups attack ticket counters of El Al, the Israeli airline, in Rome and Vienna.

Sources: Ronald Stockton, professor of political science, University of Michigan (Dearborn,); and the United Nations.

How Israelis View the Palestinians

Describing what Israelis think about Palestinians is like trying to define an American position on tax reform. Something ought to be done, everyone agrees, but both the means and the end result are subject to vigorous debate.

At one end of a very complex spectrum, Rabbi Meir Kahane asserts that all Palestinians must be routed from “greater Israel.” At the other end are Jewish intellectuals and peace activists who advocate establishing a Palestinian state—even at the expense of keeping secure borders. An Israeli political analyst, Dr. Naomi Chazan of Hebrew University, says the Palestinian problem has been at the center of more heated confrontation in Israel over the past five years than at any other time.

“It is impossible for Israelis to come to grips with themselves today unless they come to grips with the Palestinians,” Chazan said. At a public policy meeting of the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., she presented five ways Israelis view Palestinians.

Chazan began with the racist perspective of Meir Kahane, a former U.S. citizen, and a member of the Israeli parliament, the Knesset. In Kahane’s view, Chazan said, Palestinian history is dismissed or homogenized into general Arab history, which is viewed as uniformly threatening to the basis of Israeli survival. The land must be controlled by Jews, in this view, even if Israel has to sacrifice its commitment to democracy in the process. Palestinians must be expelled, Kahane says. His following is a small but vocal minority, and his views appeal primarily to urban, unemployed youth.

A related view is termed the “stereotypical” perspective. Israelis who see the Palestinians as inferior and dangerous, in this view, would opt not to expel them but to have a different set of laws apply to them. They see the Palestinian situation as being no fault of Israeli policies or leadership, but a development of Arab indifference and ignorance.

A third, centrist position, takes an aloof, detached view of the Palestinians. It views them as refugees, who are in their predicament mainly because they refused the offer of partitioned land in 1948. The solution to the Palestinian problem, these Israelis say, is functional separation with symbolic self-determination for the Palestinians.

A widely held view among Israeli intellectuals is “reluctant understanding,” Chazan said. From this perspective, Palestinians are viewed first as victims and second as people with legitimate hopes for self-determination. Here, responsibility is placed at Israel’s doorstep for the condition and status of Palestinians. Israelis of this persuasion believe their government’s policies have bred a serious nationalist movement.

Finally, a small left-wing minority identifies closely with the Palestinians, viewing them as having an undeniable right to self-determination no matter what the consequences for the Jewish state. “The plight of the Palestinians is an outcome first and foremost of Israeli government policies” in this view. These people have lost their Zionist identity and have very little political support.

Chazan pointed out that none of the perspectives she defined promote coexistence. Instead, they involve varying degrees of separation and different methods of maintaining it. However, she said, “Israeli moderates did not look for Palestinian contacts five years ago; now they seek them out avidly.” Even though this is generating confusion and confrontation among Israelis, she said, it indicates a new desire to come to grips with a problem that will not go away on its own.

BETH SPRING

Elias Chacour (Galilee)

The tiny Arab village of Ibillin, a half-hour drive from the Sea of Galilee, is a cluster of low, sand-colored buildings on the sides of two hills facing one another. Fr. Elias Chacour, parish priest for Ibillin’s Catholics and two Anglican families, scribbled on the back of an envelope as his lawyer dictated a letter to the Israeli Ministry of Education. The letter spells out Chacour’s objection to Israeli policies that are hindering a dental hygiene training program he started at Prophet Elias High School (named for the biblical prophet).

Chacour founded the high school for Palestinian young people in the area, and he is particularly keen on offering vocational training that will lead to jobs. The dental hygiene program was challenged by Israeli authorities every step of the way, he said, as he arranged for teachers and equipment. Finally, he was told he would have to pay $ 1,000 each year for every student who planned on doing a required internship. Chacour, determined to “make a scandal in Jerusalem” over the issue, accepted those terms so the program could get under way. With his lawyer, he will pursue legal means to get what he considers fair treatment for his students. This sort of struggle is all in a day’s work for Chacour.

At Prophet Elias High School, 550 Palestinian students learn science, history, English, Hebrew, Arabic, and take a mandatory course in Zionism, following a curriculum designed by the Israeli ministry of education. Vocational electives include electronics and computer programming. (He purchased laboratory equipment with royalties from his autobiography, Blood Brothers, he said [Chosen Books, 1984].) More than half of the school’s students are girls, and 65 percent are Muslim.

Chacour built the school illegally, he said, because Israeli authorities would not grant him a permit. Working 12 to 14 hours a day himself, with village parents who volunteered to work under constant threat of arrest, Chacour completed the school in nine months.

He was motivated, he said, by the fact that parents in Ibillin had to send their children away to school and usually could afford to let only one son receive an education. When the building was completed, Chacour was arrested and taken to court, where he serenely told the judge, “Yes, my school is illegally built. If you destroy it, I will have to go to America and Europe to beg for money to rebuild a school destroyed by Israeli authorities.” (Later he admits: “I am known to be a troublesome boy.”)

He was released, but still received no permit. He piped water in illegally, bought a generator for electricity, and dragged a heavy extension cord from floor to floor to plug in projectors and other equipment. The school had no telephone service, so Chacour used a mobile phone unit based in his home.

Chacour battles not only with Israel’s ministry of education, but within his own soul as well. “I have a very complex identity. I am a Palestinian, I am a Christian, an Arab, and an Israeli citizen. These four sides of my identity are at war with each other. I am living with continual tension because I do not want to cherish one side more or less than the other. When an Arab is killed by an Israeli soldier, I suffer twice, because the Arab might be my relative and the Jew my friend. If you ask me who is wrong and who is right, I will tell you I think this conflict is a war of two rights. Both [Jews and Palestinians] have suffered atrocities in the diaspora and at home.”

It is particularly frustrating for him to stand by and watch many of his high school graduates get rejection notices from Jewish universities. Chacour said Palestinians apply to Western schools, but cannot afford to attend them. “Then they apply to the Eastern bloc and get full scholarships. I cannot stop them. I can’t tell them, ‘Stay illiterate, don’t go.’ ” Palestinians who study in Soviet satellite countries inevitably return with political views that are sympathetic to communism. “This is one of the major points of fear for us in the future,” Chacour said.

Chacour is a Melkite Christian, ordained in an ancient church that rejected Gnostic heresy and held to the orthodoxy of the apostles during the church’s first centuries. They are in communion with the Roman Catholic church. Chacour is captivated by the Sermon on the Mount, and he refers to Jesus as “the Man from Galilee.” He frequently speaks to groups of Americans visiting Israel, telling them, “We try to represent the Man from Galilee, Jesus Christ, the risen Lord. We like to repeat to our children, not Roman Catholic dogma or World Council of Churches dogma, but the parables that were said around this lake. I learned them from my mother.”

That is his basis for working toward reconciliation with Jewish Israelis. “I’m very grateful to this Man from Galilee, since he is risen, because there is no more distinction, no more privilege for man over woman or lord against slave. I do not accept arguments that Christians or Jews use to convince me that my home is not mine because it has been given to somebody else. My religion is not a religion of a people or a religion of race. It is very important for me as a Palestinian to remind you that there is no righteous nation on earth, and there is no dirty nation.”

What he longs for and scraps for is a chance to build his country as an equal participant in a democratic Israeli society. “That is what the churches should say, what you people from overseas should say: That this country needs to be built by Jews and Palestinians alike. Even if [the Israelis] know all your secrets and have all your weapons, they will not win. My heart will not be conquered with weapons. They have to conquer my heart by disarming themselves and disarming my fears.”