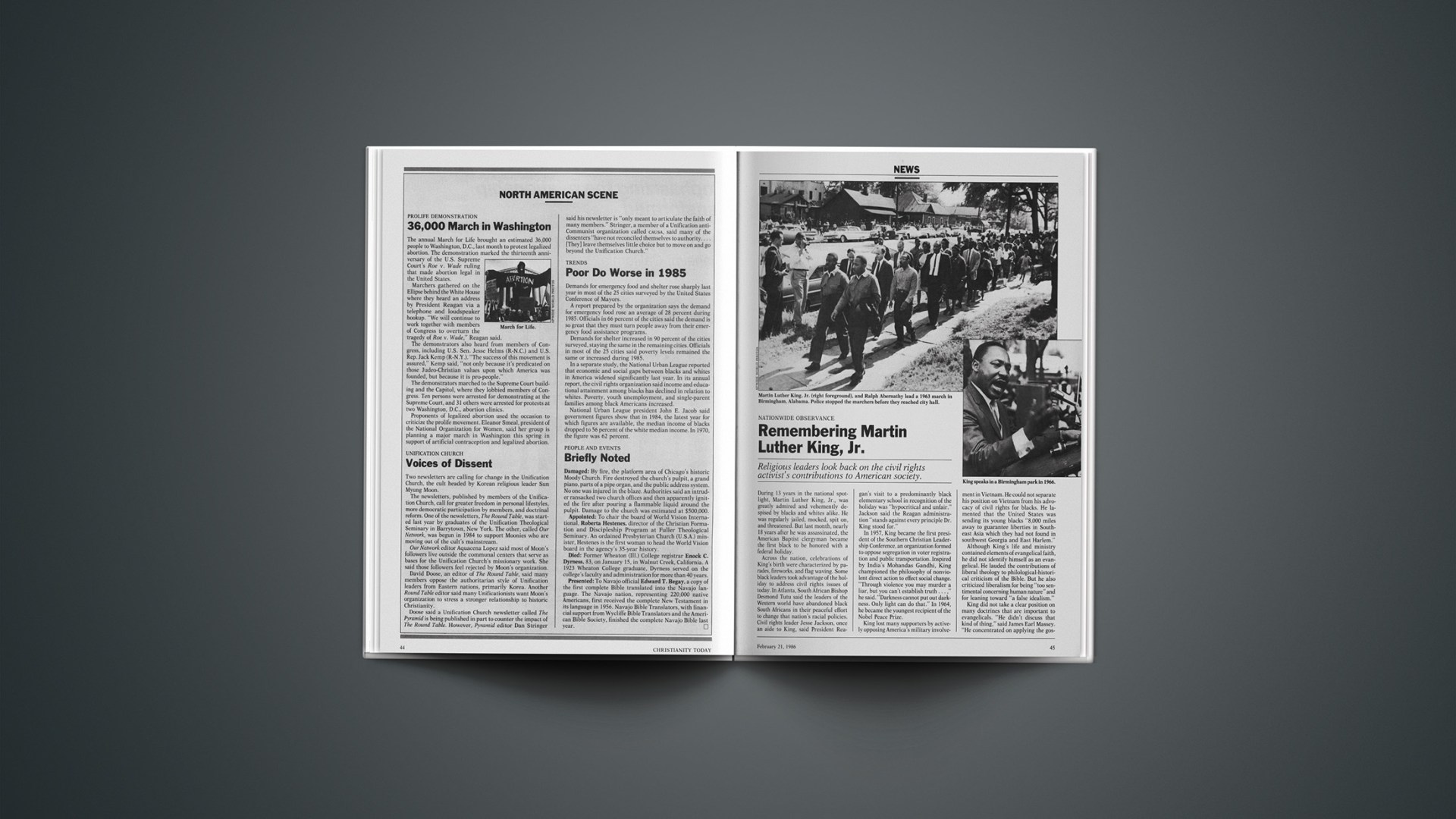

During 13 years in the national spotlight, Martin Luther King, Jr., was greatly admired and vehemently despised by blacks and whites alike. He was regularly jailed, mocked, spit on, and threatened. But last month, nearly 18 years after he was assassinated, the American Baptist clergyman became the first black to be honored with a federal holiday.

Across the nation, celebrations of King’s birth were characterized by parades, fireworks, and flag waving. Some black leaders took advantage of the holiday to address civil rights issues of today. In Atlanta, South African Bishop Desmond Tutu said the leaders of the Western world have abandoned black South Africans in their peaceful effort to change that nation’s racial policies. Civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, once an aide to King, said President Reagan’s visit to a predominantly black elementary school in recognition of the holiday was “hypocritical and unfair.” Jackson said the Reagan administration “stands against every principle Dr. King stood for.”

In 1957, King became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, an organization formed to oppose segregation in voter registration and public transportation. Inspired by India’s Mohandas Gandhi, King championed the philosophy of nonviolent direct action to effect social change. “Through violence you may murder a liar, but you can’t establish truth he said. “Darkness cannot put out darkness. Only light can do that.” In 1964, he became the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

King lost many supporters by actively opposing America’s military involvement in Vietnam. He could not separate his position on Vietnam from his advocacy of civil rights for blacks. He lamented that the United States was sending its young blacks “8,000 miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem.”

Although King’s life and ministry contained elements of evangelical faith, he did not identify himself as an evangelical. He lauded the contributions of liberal theology to philological-historical criticism of the Bible. But he also criticized liberalism for being “too sentimental concerning human nature” and for leaning toward “a false idealism.”

King did not take a clear position on many doctrines that are important to evangelicals. “He didn’t discuss that kind of thing,” said James Earl Massey. “He concentrated on applying the gospel to the social issues of his time.” Massey, professor of religion and society at Tuskegee University, knew King personally.

Speaking at a ceremony in King’s honor, Massey said the civil rights leader “sought to challenge this nation’s identity confusion and moral compromise. He knew that the widespread strife and social trauma among its citizens were generated by … a compromise with evil and a racist rationale.… The diagnosis King made 19 years ago in assessing the national sickness is still valid for present conditions in America.”

In an article published in Theology Today, James Cone, a liberal black theologian at New York’s Union Theological Seminary, said King’s theology was molded far more by the black church than by white liberalism. He said blacks “did not write essays on Christian doctrine because our descendants came as slaves from Africa and not as free people from Europe.” Cone adds that because most blacks did not have an opportunity to learn to read and write, “we had to do our theology in other forms than rational reflections.”

Black evangelical leader John Perkins, who is associated with several organizations that serve the poor, said King symbolized the aspirations of all blacks in this country. “He was to black America what David was to Israel, what Thomas Jefferson was to white America.” He said King had little chance of gaining prominence in the evangelical community because at that time, the evangelical church was on the wrong side of the civil rights movement. Indeed, King frequently observed that “eleven o’clock on Sunday morning, when we stand to sing ‘In Christ There Is No East Nor West,’ is the most segregated hour of America.”

Eddie Lane, president of the National Black Evangelical Association, said King “touched the conscience of America, and brought an end to American apartheid.… I don’t think there’s a black American living who is not indebted to Dr. King for whatever economic, social, or political status they have.”

Commenting on the qualms some evangelicals have about King, Lane said, “I read Dr. King’s sermons regularly, and I’m convinced he knew the gospel and was born again. As a black evangelical, I have no reservations about affirming the man and the movement.”

E. V. Hill, pastor of Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles, said that if King were living today, evangelicals would find no difficulty accepting his message. “What he said was in the Constitution or inscribed on the Statue of Liberty,” he said.

King would oppose America’s current foreign policy in South Africa for being gradualistic, Hill said. “Today we still see the slowness of America and of evangelicals to help the oppressed. We see gradualism. And a man who’s been hung does not want to be gradually cut down.”

Hill said evangelicals can learn an important lesson from King. That lesson, he said, is that the “will of God and the political positions of the country are not synonymous.”