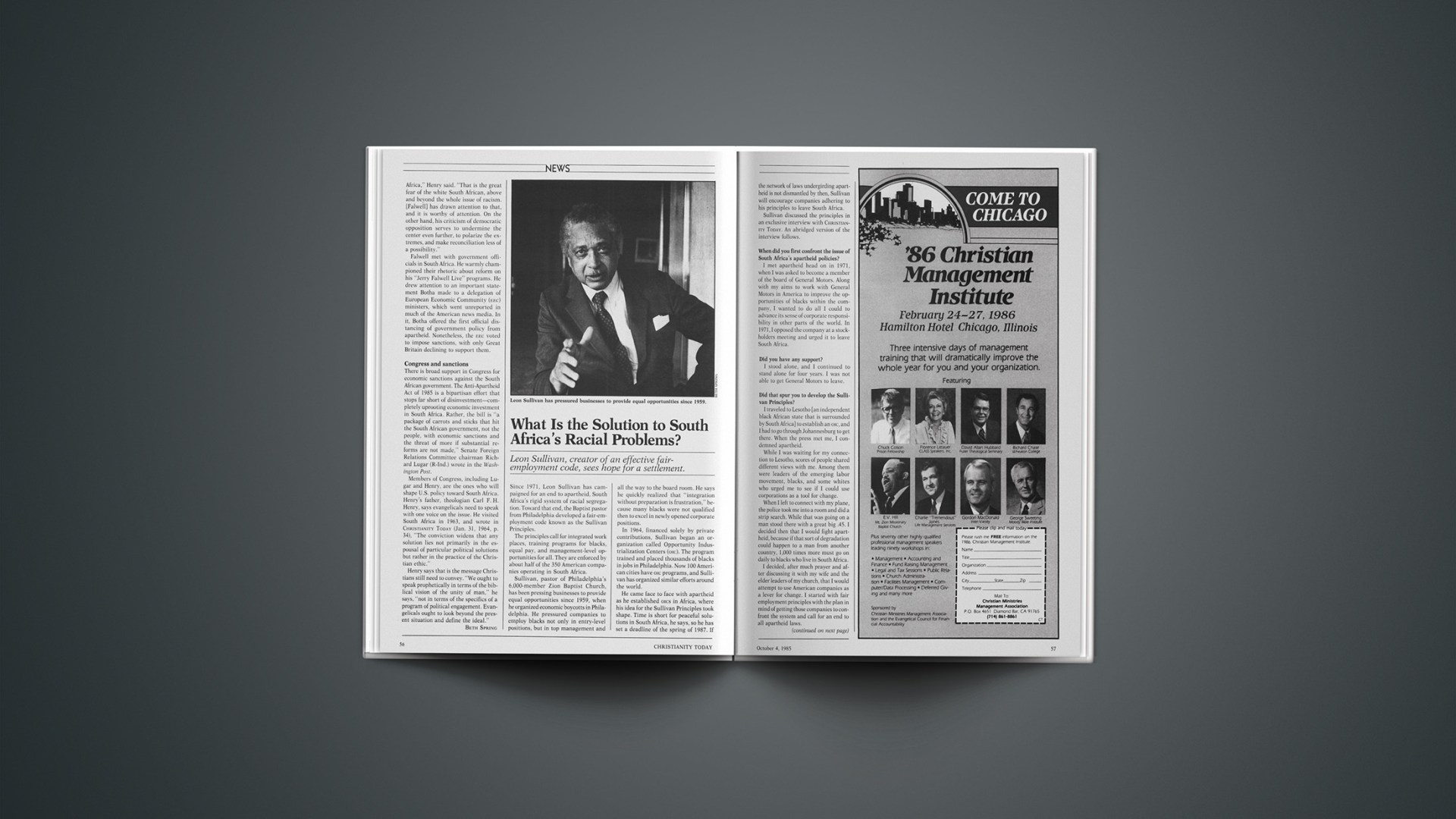

Since 1971, Leon Sullivan has campaigned for an end to apartheid, South Africa’s rigid system of racial segregation. Toward that end, the Baptist pastor from Philadelphia developed a fair-employment code known as the Sullivan Principles.

The principles call for integrated work places, training programs for blacks, equal pay, and management-level opportunities for all. They are enforced by about half of the 350 American companies operating in South Africa.

Sullivan, pastor of Philadelphia’s 6,000-member Zion Baptist Church, has been pressing businesses to provide equal opportunities since 1959, when he organized economic boycotts in Philadelphia. He pressured companies to employ blacks not only in entry-level positions, but in top management and all the way to the board room. He says he quickly realized that “integration without preparation is frustration,” because many blacks were not qualified then to excel in newly opened corporate positions.

In 1964, financed solely by private contributions, Sullivan began an organization called Opportunity Industrialization Centers (OIC). The program trained and placed thousands of blacks in jobs in Philadelphia. Now 100 American cities have OIC programs, and Sullivan has organized similar efforts around the world.

He came face to face with apartheid as he established OICS in Africa, where his idea for the Sullivan Principles took shape. Time is short for peaceful solutions in South Africa, he says, so he has set a deadline of the spring of 1987. If the network of laws undergirding apartheid is not dismantled by then, Sullivan will encourage companies adhering to his principles to leave South Africa.

Sullivan discussed the principles in an exclusive interview with CHRISTIANITY TODAY. An abridged version of the interview follows.

When did you first confront the issue of South Africa’s apartheid policies?

I met apartheid head on in 1971, when I was asked to become a member of the board of General Motors. Along with my aims to work with General Motors in America to improve the opportunities of blacks within the company, I wanted to do all I could to advance its sense of corporate responsibility in other parts of the world. In 1971, I opposed the company at a stockholders meeting and urged it to leave South Africa.

Did you have any support?

I stood alone, and I continued to stand alone for four years. I was not able to get General Motors to leave.

Did that spur you to develop the Sullivan Principles?

I traveled to Lesotho [an independent black African state that is surrounded by South Africa] to establish an OIC, and I had to go through Johannesburg to get there. When the press met me, I condemned apartheid.

While I was waiting for my connection to Lesotho, scores of people shared different views with me. Among them were leaders of the emerging labor movement, blacks, and some whites who urged me to see if I could use corporations as a tool for change.

When I left to connect with my plane, the police took me into a room and did a strip search. While that was going on a man stood there with a great big .45. I decided then that I would fight apartheid, because if that sort of degradation could happen to a man from another country, 1,000 times more must go on daily to blacks who live in South Africa.

I decided, after much prayer and after discussing it with my wife and the elder leaders of my church, that I would attempt to use American companies as a lever for change. I started with fair employment principles with the plan in mind of getting those companies to confront the system and call for an end to all apartheid laws.

Did you prefer to see American companies leave altogether, or stay in South Africa and enforce the principles?

It was not important to me whether the companies stayed or not. But as long as they stay there, they must confront the system. Once the black worker is empowered, he will speak out for himself in the workplace and in the community and in the nation and in politics. And that is happening.

Did General Motors support your fair-employment code?

Yes. They didn’t leave South Africa, but they were the first company to endorse me, and they’ve been among my strongest supporters.

How many other American companies doing business in South Africa warmed up to the idea?

I wrote letters to all of them, and I received piles of letters back telling me they weren’t going to do it, or it was against their regulations, or they could not intrude in the policies of other governments. But I went all over the country to persuade them to sign these principles, and I got 12 to do so. Then others began to come along.

How has the movement favoring divestment—pulling investment out of companies in South Africa—affected your work on the Sullivan Principles?

The divestment movement became one of my greatest helps. Companies began to come around on the principles because I said that pension funds, members of state legislatures, investors, and schools should divest their holdings in companies that do not support the principles.

What difference have the principles made for the average black worker in South Africa?

The principles have started a revolution in industrial race relations. When they were initiated seven years ago, a black South African was not even regarded legally as a worker. When I started, there were no black managers or supervisors to speak of. Now about 30 percent of administrative supervisors are black. At first, no unions were recognized. Now all American companies must recognize independent free black trade unions. Companies have even built new buildings to facilitate integrated work places.

Are the principles evolving into a larger solution to the problem of apartheid, as you initially hoped?

The principles have served as a platform outside the work place for people who stand up for equal rights. The problem in South Africa is not unemployment or even equal opportunity in the work place, but freedom. The principles cannot solve the problems of South Africa. But they can be part of the solution—along with international trade unions, international churches, leaders of nations, governments, the United Nations, and most of all, the rising tide of black leaders within South Africa.

You have set a deadline of the spring of 1987 before you call for stronger action. Will that give South Africans enough time to resolve their conflicts?

That deadline holds even though it was established before the current state of emergency. If the companies of the world will take a stand and call for the ending of statutory apartheid, it can end in these following months.

If statutory apartheid is not ended by the spring of 1987, then in spite of the fact that it will mean the loss of jobs and the loss of American influence in South Africa, I’m saying that there should be a total U.S. embargo against South Africa, the withdrawal of all American companies, and the breaking of diplomatic relations.

Is a peaceful solution still possible?

I am hoping for a peaceful resolution, because a nonpeaceful resolution will mean millions of lives lost and the obliteration of a nation. It could mean the involvement of an entire continent and much of the rest of the world. If any way can be found for an end to apartheid without tremendous destruction, it must be tried. With the help of God, I think it is possible.

Since the beginning of the 1984–85 school year, friction between fundamentalist church schools in Nebraska and the state government has all but ceased. A regulation passed last year dropped the requirement that teachers in private schools be certified by the state (CT, Oct. 5, 1984, p. 85). Since that was the major point of conflict, the problem was solved for most church-related schools.

However, one Nebraska pastor is still caught in the grip of the conflict. Last year, Robert Gelsthorpe and his North Platte Baptist Church were each fined $200 every day their church-run school remained open in violation of what then was state law. A 14 percent interest rate is being charged against the debt, bringing the total amount owed by Gelsthorpe and his church to about $50,000.

Gelsthorpe and his church refuse to pay the fine. He also has declined to pursue a compromise that would require the pastor to pay only a small percentage of the fine.

“We’ve been fined for willingly disobeying a judge,” Gelsthorpe said. “We never willingly disobeyed anyone; we willingly obeyed our God.”

Judge John Murphy, who imposed the fine, said he did not have the legal authority to waive the penalty.

Lincoln County prosecutor Charles Kandt said he will take action against Gelsthorpe before moving against the North Platte Baptist Church. He said the first step will be to foreclose on Gelsthorpe’s house.

Kandt estimated that the money gained from selling the house would pay only about half of Gelsthorpe’s portion of the debt. By collecting the remainder of the fine, he said, he expects Gelsthorpe to lose everything he owns.

For Kandt, who has made public his Christian faith, this has been a difficult case to prosecute. Kandt said, however, that not to enforce payment of the fine would constitute an “undercutting of the court’s authority that would be dangerous.”