Looking back at a controversy that was destined to die.

Atlanta, GA—God, creator of the universe, principal deity of the world’s Jews, ultimate reality of Christians, the most eminent of all divinities, died late yesterday during major surgery undertaken to correct a massive diminishing influence.

Twenty years ago. The time when talk about God’s death moved out of college classrooms and into America’s homes. From the above obituary in Motive, a Methodist student magazine, to the cover story in Time a year later, the press heralded the radical Death of God movement (termed “theothanatology”), catapulting it momentarily into the national spotlight.

Theology suddenly became a source for graffiti on the walls of the New York City subway. International leaders were interviewed for their response to the announcement of the demise of God. One Russian diplomat was quoted as saying, “Good riddance.” Dwight D. Eisenhower was alleged to have said, “Gosh, I didn’t know he was sick.” And the puckish comment attributed to a former U.S. President in Independence, Missouri, was simply, “It’s a——shame!” Said Billy Graham: “That’s funny, I talked to him this morning.”

The 20 years since this acknowledged media event have found significant shifts in theological thinking, with a newfound adherence in and insistence on the traditional tenets of the faith. But what effect has the passage of time had on the ministries of those radical theologians who, according to Time, formed the movement’s nucleus? And are there lessons still to be learned, and warnings to be heeded, that a look back might offer us in 1985?

Regaining Relevance?

Was the Death of God movement a simple fad? Can we explain it simply in terms of a journalistic sham created by Time magazine for its sensational news value? By no means. Though the movement did attract its share of journalistic hooplah, it reflected serious and sober thought from the minds of professional theologians. However, as a media bombshell the Death of God controversy appeared as a de novo explosion—a temporary blip on a radar screen; and then it was over. Actually, the movement was the highly visible tip of a long-enduring iceberg, an iceberg that represented a crisis.

Radical theology takes its name from the Latin word radix: root. It seeks to grapple with root issues in times of crises. The crisis it addresses has several facets, at once cultural, ethical, ecclesiastical, political, historical, and religious. The root problem is that modern man lives in an environment where many human beings experience a profound sense of the absence of God. Where religion flourishes it seems to have little cultural relevance. The historians have declared this the “Post-Christian Era.” There is a cultural sense of the loss of transcendence. Modern men and women feel trapped within the closed walls of “this-sidedness.” There seems to be no access to the eternal or the transcendent. Nature has been demythologized. History has been desupernaturalized; ethics have been de-absolutized.

The church faces a serious crisis of relevance. If, for example, we discover that the traditional categories of Christian religion are no longer credible, what is left for the church to do? If the Incarnation is a myth and the crucifixion of Christ merely a Roman tragedy, what do we do with billions of dollars of church property, thousands of professionally trained clergy, and millions of church members? Do we quietly close the doors of the churches, give pink slips to the clergy, turn over our assets to the United Fund, and apologize to our members, saying, “Sorry, we were wrong. There is no God and the biblical Jesus is a myth”?

This crisis was sharply felt by nineteenth-century liberal theology. Emil Brunner called it a crisis of “unbelief.” What do you do with a confessing community that has lost its faith? Usually two things happen. First, the church finds a new agenda in order to be relevant. Second, the church rewrites its theology to fit the new agenda. This requires a kind of candor found in the bishop of Woolwich’s Honest to God and the boldness articulated in Harvey Cox’s The Secular City.

The Big Three

When the Death of God brand of radical theology is mentioned, four names are immediately brought up: William Hamilton, Thomas Altizer, Paul Van Buren, and Gabriel Vahanian. This inner circle is customarily seen as the core group of theothanatologists. Ironically, they were never banded together as a group and their views were hardly monolithic. It is questionable whether fairness even allows Vahanian membership in the group. The remaining triumvirate came at the crisis of radical theology from quite disparate paths.

• William Hamilton. Hamilton (in the 1960s he was a professor at Colgate Rochester Divinity School) once defined radical theologians as “men without God who do not anticipate his return.” He summarized the situation in an essay in Radical Theology and the Death of God:

“What does it mean to say that God is dead? Is this any more than a rather romantic way of pointing to the traditional difficulty of speaking about the holy God in human terms? Is it any more than a warning against all idols, all divinities fashioned out of human need, human ideologies? Does it perhaps not just mean that ‘existence is not an appropriate word to ascribe to God, that therefore he cannot be said to exist, and he is in that sense dead’? It surely means all this, and more.… This is more than the old protest against natural theology or metaphysics; more than the usual assurance that before the holy God all our language gets broken and diffracted into paradox. It is really that we do not know, do not adore, do not possess, do not believe in God.… God is dead. We are not talking about the absence of the experience of God, but about the experience of the absence of God.”

Hamilton’s passion was for human dignity to be found in this world. He had little time for religious preoccupation with an otherworldly piety that ignored present human need. He was critical of theologies that looked to God as a problem solver, a kind of cosmic bellhop who was always on call. Yet he wanted to retain Jesus as a model for radical living, so such a Jesus had to be unwashed and free of mythological trappings. Jesus is not an object of veneration or even of faith, but a “place-to-be.” Jesus becomes a kind of symbol for authentic action. (Hamilton anticipated elements of the theology of hope and of liberation theology.)

• Thomas J. J. Altizer. Altizer taught theology at Emory University in the sixties. His early contributions to the Death of God movement were most fascinating. His flamboyant style added sparks to the movement. His thoughts were expressed in almost poetic fashion, with staccato bursts of insight. Some saw his views as a kind of radical eclecticism with a dose of oriental mysticism here, a dash of Hegel there, and a pinch of biblical Christianity mixed in.

Altizer spoke of the death of God as a historical event, linked with Incarnation and Cross. It was a cosmic act of transition within God by which the transcendent God became immanent. To him, there is a sense in which the God-above-us had to die in order for him to become the God-with-us.

Altizer’s views represented a kind of Hegelian kenotic theory. God died in a cosmic act of self-emptying. God dies—but he still “is.” Altizer still spoke of God—but in a new form, a new mode of being, a new kind of action.

Altizer looked to Kierkegaard as the true father of modern theology. What Kierkegaard began was consummated in Nietzsche. Altizer said, somewhat complicatedly:

“The proclamation of the death of God—or, more deeply, the willing of the death of God—is dialectical: a Nosaying to God (the transcendence of Sein) makes possible a Yes-saying to human existence (Dasein, total existence in the here and now). Absolute transcendence is transformed into absolute immanence; being here and now (the post-Christian existential ‘now’) draws into itself all those powers which were once bestowed upon the Beyond. Consequently, Nietzsche’s vision of Eternal Recurrence is the dialectical correlate of his proclamation of the death of God.… Only when God is dead can Being begin in every now” (from the chapter “Theology and the Death of God,” in Radical Theology and the Death of God).

Here salvation is linked both to a cosmic event in the past and a kind of vertical, punctiliar here-and-now experience.

• Paul Van Buren. Van Buren, at Temple University in the sixties, chiefly contributed to the Death of God movement by his book The Secular Meaning of the Gospel, published in 1963. His approach leaned heavily on linguistic analysis. His work displayed an acute awareness of the God-talk crisis and left him sharply critical of both Barth and Bultmann. He expressed an indebtedness to Bonhoeffer’s “religionless Christianity.”

Van Buren noted that modern secular man is empirical in his orientation. The crisis of language has left the word “God” either meaningless or misleading. He cited, for example, Anthony Flew’s famous parable that concluded with the assertion that the God-hypothesis had suffered “the death of a thousand qualifications.” Van Buren analyzed traditional theological categories and found them linguistically lacking. He recast the biblical resurrection accounts away from empirical assertions into what he called a “discernment situation.” He writes:

“It seems appropriate to say that a situation of discernment occurred for Peter and the other disciples on Easter, in which, against the background of their memory of Jesus, they suddenly saw Jesus in a new and unexpected way. ‘The light dawned.’ The history of liberal theologians have cast the same basic outlook into different forms, and are still with us. Lacking the biblical view of Christ, they may turn up as one group among the “liberation theologians,” or they may emphasize oriental mysticism, or drugs—or something else. The possibilities are endless.

The Bible presents God as transcendent—high over all, limitless and free. Yet it also says he became incarnate—God the Son took upon himself a flesh-Jesus, which seemed to have been a failure, took on a new importance as the key to the meaning of history. Out of this discernment arose a commitment to the way of life which Jesus had followed” (The Secular Meaning of the Gospel).

Van Buren called for a clarification of Christianity. It has to do, fundamentally, with man and his behavior. Jesus is the ideal model of human freedom and responsibility. His freedom is contagious.

As a movement, the Death of God sensation is over. The serious elements that produced it continue, as theology struggles with issues of contemporary relevance, and with philosophical crises of metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and history. Radical theology goes on—both in and out of the church. It resulted from nineteenth-century religious liberalism and naturalism, one piece of which the press made into a Death of God “movement.” But other and-blood human nature. Radical theology faces many complex issues, but none are more serious than the supreme crises of faith in both a transcendent God and an objective Incarnation.

Its characteristic way of handling such matters puzzles the conservative: radical theologians insist on attaching unconditional importance to Jesus of Nazareth. But when asked who this Jesus is, they show a tendency to view him in strictly conditional terms, a person bound by time and space. It is hard to see how an earthbound Jesus can, to them, also be the central figure of such limitless importance.

Where are they now?

Two decades have passed since Hamilton, Altizer, and Van Buren had their hour upon the stage. Has the candle been extinguished as in the idiot’s tale?

CHRISTIANITY TODAY asked Arthur Lindsley to contact these men for an update on their lives, their thoughts, their feelings. He was able to speak with all three.

• William Hamilton. Hamilton has moved from Colgate Rochester to Portland State University. He currently teaches religious studies, intellectual history, and English literature. His new book, soon to be released, is titled Melville and the Gods.

Hamilton reminisced about the sixties in a sanguine spirit. He said, “It was a lot of fun.” He thinks the press made the “movement”—tying together men who had little or no scholarly contact. Since then, however, Hamilton has maintained a regular dialogue/exchange with Altizer.

The movement was costly to Hamilton’s career. He was urged by his colleagues at Colgate Rochester to leave that institution because of the possible effect of his views on young people entering the ministry. He has broadened his teaching into literature and art.

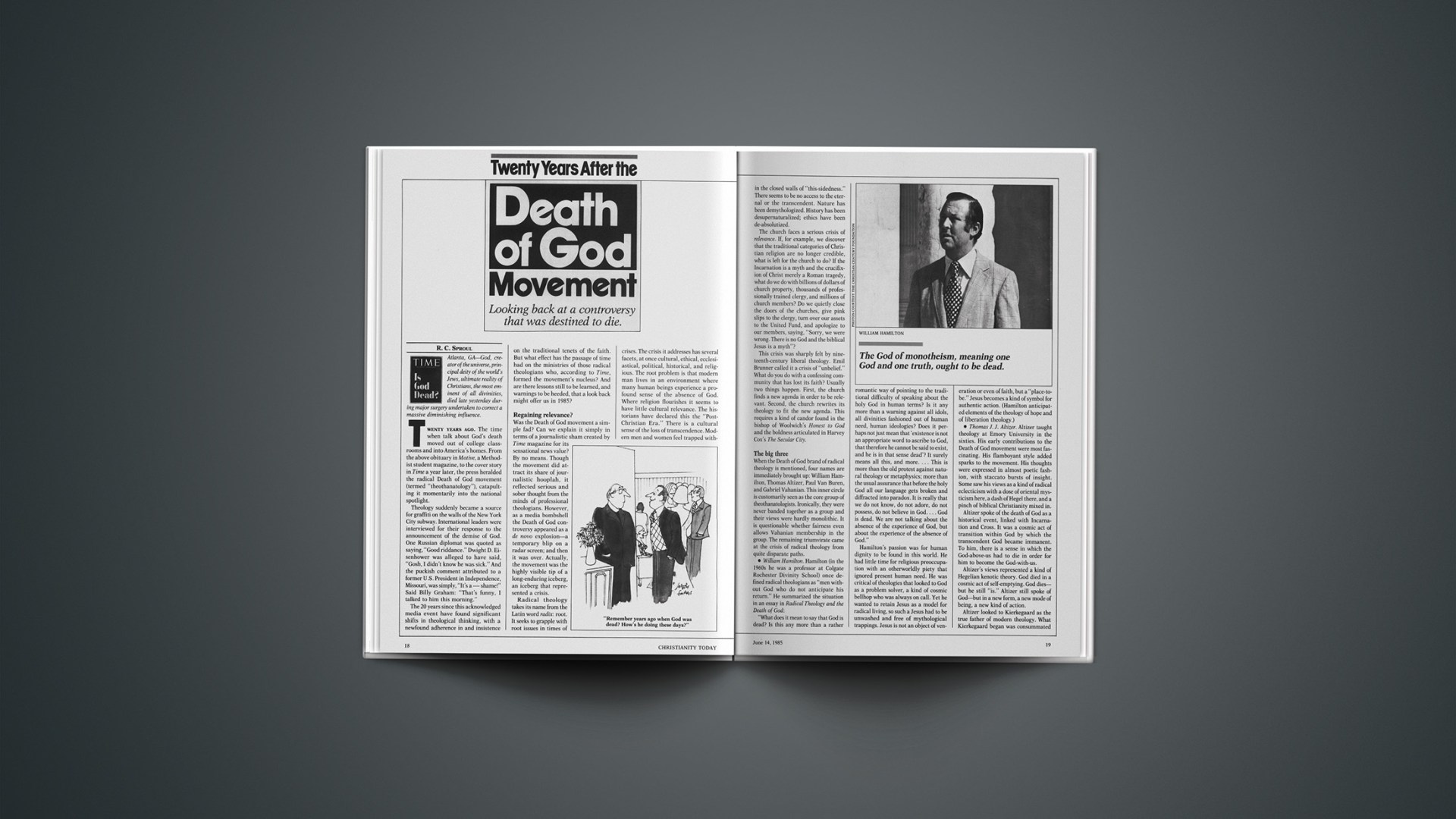

Hamilton remains concerned about the problems facing modern man. He sees radical theology as having the modest function of reminding people of the danger of religious beliefs. This danger is, he believes, heightened in the hands of right-wing Christianity. Hamilton is concerned about religious intolerance. He said, “The God of monotheism (meaning one God and one truth) ought to be dead.” He recognizes the destructive character of human sinfulness. People violate people. The historical Jesus has much to teach us about this.

Since the sixties, William Hamilton has had to live his life outside the church and seminary. His views forced him to relocate on the periphery of the religious community.

• Thomas Altizer. Like Hamilton, Altizer has moved from his position at Emory University, that of teaching theology. Presently he teaches English and religious studies at the State University of New York at Stonybrook. His newest book will bear the title History as Apocalypse, with major chapters on Dante, Milton, Blake, and Joyce.

Altizer is still a Hegelian but sees himself as less sectarian in his view of history than he was. The movement of the sixties was shaped, he observed, by the optimism, consciousness, and awareness of that decade. He sees the contemporary rift between the secular culture and the church as being greater today than then.

For Altizer the lasting value in the Death of God movement is its focus on the relationship of the center of faith to the center of the world.

• Paul Van Buren. Van Buren has also moved, leaving Philadelphia’s Temple University. He now lives in Boston. Of the three men interviewed, Van Buren expressed the most significant change of viewpoint. His substantive changes were set forth in the June 17, 1981, issue of the Christian Century. Van Buren’s chief interest now is in systematic theology.

Van Buren studied under Karl Barth. Later he went through what he calls a “positivistic Wittgensteinism phase.” He said that his involvement in the Death of God movement was created out of thin air by the press.

Recently he selected 20 theologians from around the world to go to a Jewish study center in Jerusalem for nine weeks. The focus was on dialogue with Jewish scholars on the subject of Christology. He hopes to complete a systematic theology that focuses on the people of Israel. He said, “When you change your teaching on ‘Who is Israel?’ everything in theology is affected.”

Van Buren acknowledges a continued debt to his mentor, Karl Barth, saying of Barth that he was “a fantastically stimulating teacher.”