U.S. Sen. Mark Hatfield (R-Ore.) is a moderate in a conservative party, an evangelical Christian who supports a nuclear freeze and opposed the Vietnam War. On issues, he has provoked more than his share of controversy. His personal integrity, however, has remained consistently above reproach.

However, a sudden squall of newspaper articles last month threatened to change that enduring image. Beginning with two Jack Anderson columns, press reports trained a blinding spotlight on the charge that real estate fees paid to Hatfield’s wife, Antoinette, influenced the senator’s support for a proposed trans-African pipeline project.

Basil Tsakos, a Greek entrepreneur who came to Washington to promote the pipeline, retained Mrs. Hatfield as a real estate agent. He paid her a total of $55,000 for showing luxury properties to his wife and helping her decorate the condominium they bought. Meanwhile, Hatfield arranged meetings between Tsakos and top U.S. government officials and business executives.

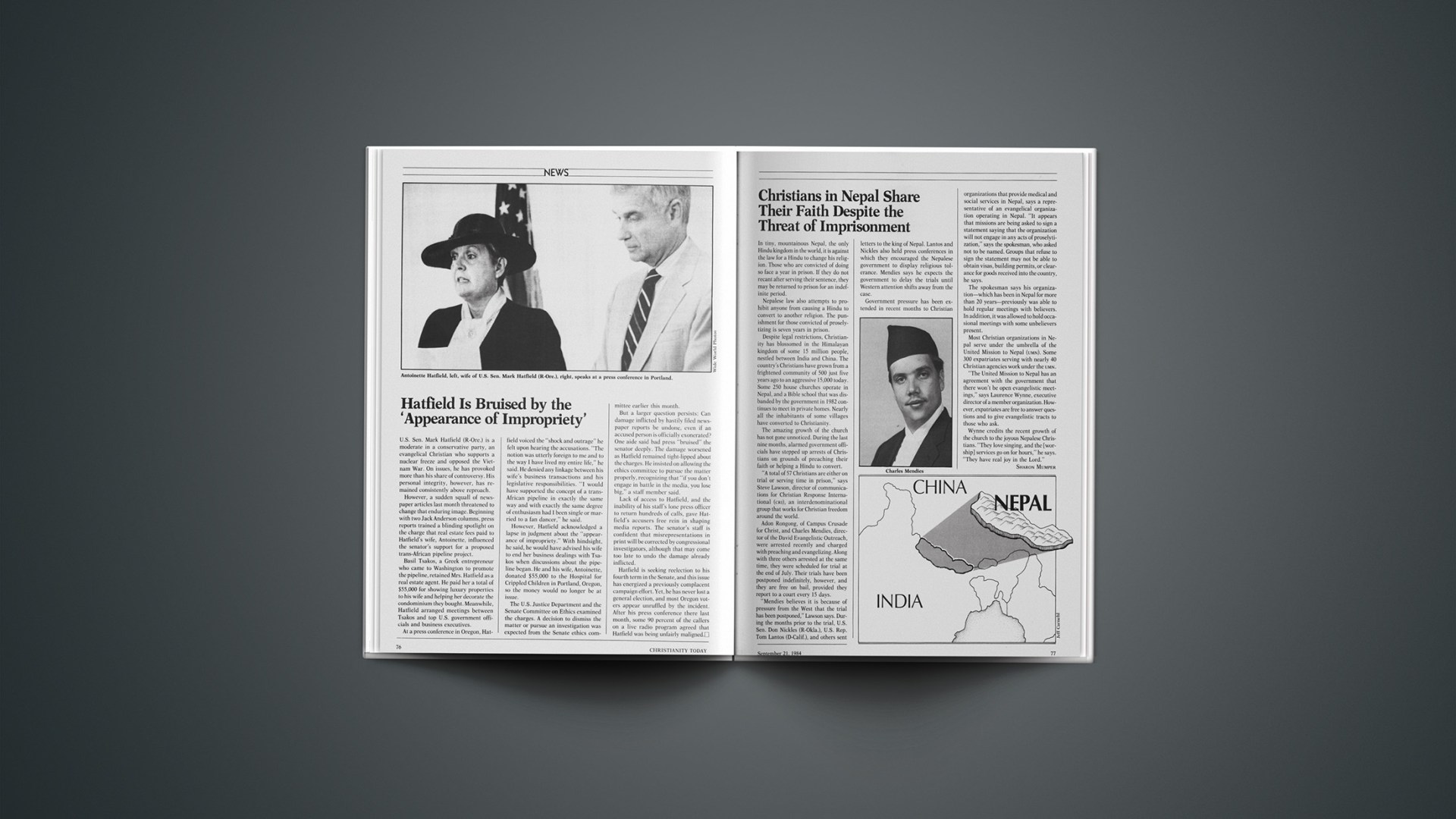

At a press conference in Oregon, Hatfield voiced the “shock and outrage” he felt upon hearing the accusations. “The notion was utterly foreign to me and to the way I have lived my entire life,” he said. He denied any linkage between his wife’s business transactions and his legislative responsibilities. “I would have supported the concept of a trans-African pipeline in exactly the same way and with exactly the same degree of enthusiasm had I been single or married to a fan dancer,” he said.

However, Hatfield acknowledged a lapse in judgment about the “appearance of impropriety.” With hindsight, he said, he would have advised his wife to end her business dealings with Tsakos when discussions about the pipeline began. He and his wife, Antoinette, donated $55,000 to the Hospital for Crippled Children in Portland, Oregon, so the money would no longer be at issue.

The U.S. Justice Department and the Senate Committee on Ethics examined the charges. A decision to dismiss the matter or pursue an investigation was expected from the Senate ethics committee earlier this month.

But a larger question persists: Can damage inflicted by hastily filed newspaper reports be undone, even if an accused person is officially exonerated? One aide said bad press “bruised” the senator deeply. The damage worsened as Hatfield remained tight-lipped about the charges. He insisted on allowing the ethics committee to pursue the matter properly, recognizing that “if you don’t engage in battle in the media, you lose big,” a staff member said.

Lack of access to Hatfield, and the inability of his staff’s lone press officer to return hundreds of calls, gave Hatfield’s accusers free rein in shaping media reports. The senator’s staff is confident that misrepresentations in print will be corrected by congressional investigators, although that may come too late to undo the damage already inflicted.

Hatfield is seeking reelection to his fourth term in the Senate, and this issue has energized a previously complacent campaign effort. Yet, he has never lost a general election, and most Oregon voters appear unruffled by the incident. After his press conference there last month, some 90 percent of the callers on a live radio program agreed that Hatfield was being unfairly maligned.