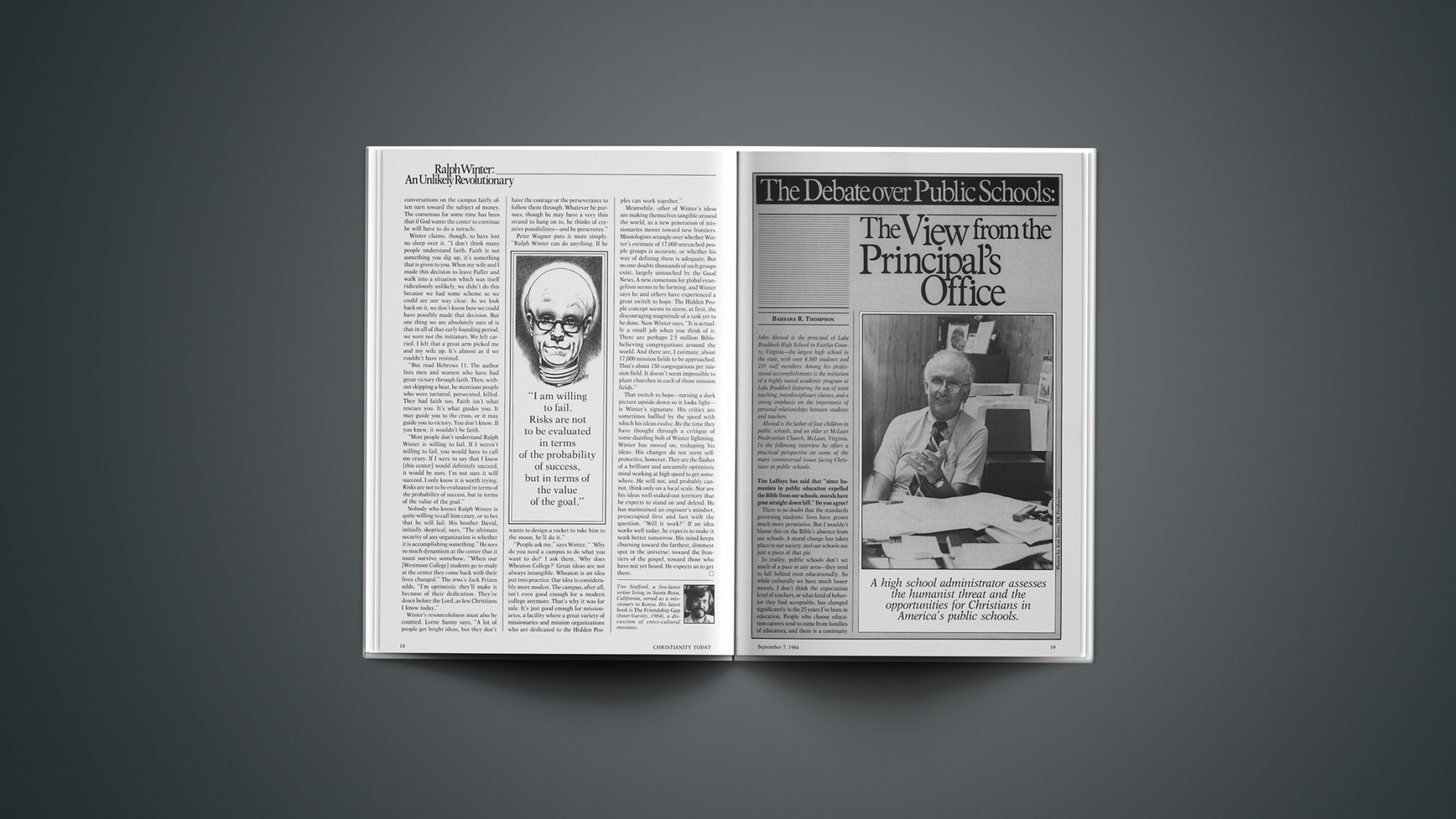

John Alwood is the principal of Lake Braddock High School in Fairfax County, Virginia—the largest high school in the state, with over 4,300 students and 235 staff members. Among his professional accomplishments is the initiation of a highly touted academic program at Lake Braddock featuring the use of team teaching, interdisciplinary classes, and a strong emphasis on the importance of personal relationships between students and teachers.

Alwood is the father of four children in public schools, and an elder at McLean Presbyterian Church, McLean, Virginia. In the following interview he offers a practical perspective on some of the many controversial issues facing Christians in public schools.

Tim LaHaye has said that “since humanists in public education expelled the Bible from our schools, morals have gone straight down hill.” Do you agree?

There is no doubt that the standards governing students’ lives have grown much more permissive. But I wouldn’t blame this on the Bible’s absence from our schools. A moral change has taken place in our society, and our schools are just a piece of that pie.

In reality, public schools don’t set much of a pace in any area—they tend to fall behind even educationally. So while culturally we have much looser morals, I don’t think the expectation level of teachers, or what kind of behavior they find acceptable, has changed significantly in the 25 years I’ve been in education. People who choose education careers tend to come from families of educators, and there is a continuity of moral feeling. While some people want to make the school a fall guy for students’ behavior, it is closer to the truth to see the schools suffering from, and attempting to combat, a moral deterioration in society.

Do you think public schools should play a primary role in upholding moral values?

I would like to think they should play a key role. Boys and girls spend a lot of time in school, and there is opportunity to make a significant impact on their lives. As Christian educators, we can communicate to students that they are special people—created in God’s image—and that they ought to be proud of that fact. We can encourage our fellow staff members to practice and communicate basic values, such as truthfulness and honesty. Sometimes we tend to think these values are taught by punishing their opposites, and that often has to be done. But students learn from consistency. If their principal, their teachers, and their counselors are all demanding honesty, they themselves will buy into it as one of the good things in life.

Many conservative Christians see the public schools as a philosophical battleground pitting secular humanist thought against our Judeo-Christian heritage. Is this a fair assessment of what’s going on?

If there is a battle going on, there are a lot of schools where no one knows it. And maybe that’s the New Right’s concern. They see a subtle but conscious undermining of Christian values.

What teachers see, however, is a classroom full of students who aren’t interested in anything. So, for instance, to get a class interested in a writing unit, a teacher might have the students write a horoscope. When the assignment gets home to Christian parents (and even non-Christian parents), there is justifiably a strong reaction. Those in the New Right might even sense a conspiracy—that the teacher has a hidden motive for using this particular unit.

The teacher does have a hidden motive—he wants to teach the kids to write. While there might be a few teachers who are consciously committed to secular humanism as the salvation of their students’ lives, most of them are simply trying to generate interest in any direction they can find it.

Are there parameters within which teachers operate when determining the proper ways of generating student interest?

Of course. And when it comes to such potentially volatile subjects as, for example, horoscopes, we as a school staff try to determine an appropriate course of action with the students’ best interests in mind.

Have the efforts of the New Right had a discernible effect on the practice or policies of the public schools?

It has made us more sensitive to curriculum problems, and to the effects certain texts and exercises are having on our students. At the same time, there is a sense in which the New Right doesn’t want public schools: it wants Christian schools. Tim LaHaye has argued that the schools could at least adopt the last six commandments. There really is no controversy over those commandments. But there are a lot of battles and a lot of scars with respect to texts and language and sex education. Public schools wrestle with how to meet the needs of special interest groups and still address issues.

Do you find that non-Christians involved in education tend to identify evangelical Christianity with the New Right?

There is no doubt that this happens. For example, the New Right makes the statement that when sex education came into public schools, morals went down the drain. But there were all kinds of things going on in life with a minimum of sex education. That just isn’t a very palatable conclusion to propose without substantial data. With that kind of thinking in the air, a lot of people who are otherwise receptive to the Christian faith begin to say, “This just doesn’t hold water.” They turn off completely because the credibility level is so low. It makes it very difficult for other Christians to make an impact.

One of the most troubling results of all this negative publicity is that Christian teachers in public schools are becoming reluctant to share their faith with students. Other teachers don’t think twice about giving their views in the classroom, whether they be political or philosophical. That’s as it should be; every person in a public school, including the teacher, has a right to share his or her opinion and perspective.

Somehow Christian teachers, the ones most intent on proclaiming the gospel to please their Lord, feel trapped and silenced by their mistaken impression that it is illegal to talk about their religious beliefs. Even when I encourage my own Christian teachers to be more vocal about their spiritual commitment, they get nervous and tell me they will get in trouble for speaking frankly. The truth is, unless a teacher gets on a soapbox and becomes dogmatic, he or she is perfectly free to say, “This is my perspective as a Christian. These are the beliefs I hold, and this is how I arrived at them.”

There are a lot of subjects, like history and literature, that can’t be studied without examining religious beliefs. In this context, I find that non-Christian teachers often talk more freely and accurately about the Christian faith than Christian teachers, who fear they will be accused of violating the separation of church and state. It is the students who are shortchanged by this silence. If the Christian viewpoint is the only one they never hear, they get a one-sided picture of what life is all about.

As a Christian public school administrator, how do you handle differences of opinion about value-laden and controversial subjects like biology?

First of all, we have to accept the fact that when a subject is taught, the perspective of the teacher will be there. That being the case, it is important to make sure the teacher is not presenting just his or her own perspective.

For instance, a teacher might feel so strongly about Darwin’s theory of evolution that he teaches it as a fact. That’s not giving the kids a fair shake. They need to know what the options are; they need to hear, “Now look at the possibility of creation. Isn’t that just as plausible?”

More recently, we’ve moved into creation science—which isn’t faring too well in the courts. I think that is too bad. But again, if I were a teacher, I would want to make sure that even if my students accepted God as Creator, they wouldn’t feel forced to buy into a package that included, for example, an Earth 10,000 years old. There are many ways God could have created the world, and there is no consensus among Christians as to how he went about it. Teachers shouldn’t be locked into saying, “This is the way it was.” Instead, they should be free to present the whole spectrum of problems and possibilities. If there isn’t a God, where did everything come from? And if there is a God, then there are any number of ways he might have created the universe. Maybe it was a “Big Bang.” The point is that everything we say at this time is theory and needs to be presented that way.

What do you think parents should do if they discover their children are getting a viewpoint they disagree with presented dogmatically in the classroom?

I think they should stand up and holler. If the teacher is not being fair in the presentation, that needs to be corrected. And if materials are objectionable, there are options. The purpose of an English assignment, for instance, is usually broad-based, and any number of novels could meet that purpose.

I don’t think you could eliminate every book that someone wants eliminated. I myself am quite prudish and don’t want to use books with much at all that is questionable. Then I go home and turn on the television and wonder if I am crazy. I won’t come close to letting those kinds of things be discussed in class, and yet students are home watching them every night.

Can you give us an example of a textbook controversy you were involved with?

The first year I came to Fairfax County a Christian parent took me to task for letting a teacher use Brave New World. The teacher, in turn, asked me if I had read the book—a fair question for a teacher to ask her principal! I took the book home, read it, and found it fascinating. I couldn’t find anything wrong with the way the teacher was presenting the material, and met with the parents to tell them so.

I eventually ended up on a Christian radio show discussing the matter with a local minister. He asked me a stream of belligerent questions: “What have you to say, Mr. Alwood, about line 7 on page so-and-so?” The line would be a string of swear words that had nothing to do with the course of the book. Our entire discussion was futile, and a good example of what we as Christians do to each other when we take a “do’s-and-don’ts” approach to our faith. There are no easy answers for these troublesome and complicated issues. We need to work them through with genuine love and respect for one another.

But how do you balance the demands of intellectual freedom with the need to protect students from constant bombardment by the seamier elements of life?

It’s not easy. In general, I believe the more you know, the better decisions you can make. I don’t try to limit the presentation of information, nor the freedom with which something can be discussed. Now, if it is a question of a risqué approach versus an intellectual one, that would give me concern. When we can find good, solid materials with little if anything “alluring” in them, then let’s use them.

What role do you think the community, and the church as part of the community, should play in the approval of textbooks?

The schools belong to the people, and over the years I’ve tended to think they should, therefore, have a great deal of influence in making these decisions. I no longer feel that way. Most community groups have narrow interests and carry a particular banner. When it is time to make decisions about budgets and textbooks, or whether to offer sex education and psychology, there aren’t many broad-based groups around.

There is still room for sound Christian input into the school curriculum, but, unfortunately, we don’t get it. We’ve been given material by Christian groups on Ronald Reagan that claimed, among other things, that Reagan is the redeemer of our nation. You throw that at a group of history teachers and they aren’t going to buy it. And if it bothers me as a Christian, just think what it does to them!

At the same time, all kinds of good material coming from Christian authors is being neglected. Why isn’t someone encouraging the schools to use the works of C. S. Lewis or Francis Schaeffer? There is a danger that in reaction to the extremism of the New Right, some very good Christian material will be thrown out as well. The New Right won’t be prepared to defend these worthwhile authors; and evangelicals, because they aren’t involved, won’t even know what is happening.

How do you feel about sex education in the public schools?

The real question is what is the school’s role in handling something many consider a nonschool problem? Schools are here to teach, some would say, and sex education is none of their business.

But what school is all about is the lives of kids; and an important part of their lives concerns what is happening to them sexually. I’ve found families have a hard time dealing with sex, and I’m not sure but what the Christian community isn’t the worst of all.

My own position is that the schools need to provide enough information to make conversation comfortable between kids and parents, and then they can take it from there. If we just leave the subject cold, or ignore it completely, I’m not sure who we are helping.

Jesus chastised the religious leaders of his day for concentrating on minor points of the law while neglecting weightier matters. Do you think the Christian community is in danger of making the same mistake with respect to public schools?

Yes. The prayer-in-school issue is an example. About nine years ago I heard that our state had passed a law requiring a moment of silence so students could pray. We did this for a week, and then I checked around to see how it was going. It wasn’t one of the great moments in our school, perhaps because our size prevented the personal dimension that is needed. In any case, it wasn’t working arid I didn’t want to do it anymore. I was relieved when I found out it wasn’t required in the first place and that I wasn’t legally bound to do something I knew was ineffective.

The point is that we sometimes do things for the sake of doing them when, in fact, they are meaningless. At faculty meetings prior to the school year, I usually do quite a bit with Scripture and prayer. But I have to be careful that I don’t become just someone doing something to be seen, rather than someone doing something because it has spiritual meaning.

What positive issues could Christians focus their energies on?

Right now school boards are being pushed to the wall with respect to what organizations they will allow in the school; many Christian groups, like Young Life and Fellowship of Christian Athletes, are being targeted. The situation is getting bad, and I don’t think it is legally necessary. As Christians, we need to make sure that the kinds of people we want relating to our kids are allowed in the schools.

I once had a parent call me to complain that her daughter was meeting a Young Life staff person twice a week to talk over what’s right and wrong in sex relationships between boys and girls. I told the mother she was lucky to have someone willing to spend time with her daughter, giving her a straight perspective on what was good for her. We should be thankful when these kinds of people befriend our children.

If we are going to keep these Christian groups in the schools, some compromises have to be made. The Church of the Latter Day Saints, for example, has had a strong morning program for years with good moral content for students. I may not accept their theology, but I do accept their right to be in school.

How do you decide who is allowed in a public school and who isn’t?

The standard question is: “If someone wanted to form a club for fascists, would you let them?” I’d answer no. This is a judgment that a principal has to make in light of what kinds of people he wants associating with students. If there were people whom I felt shouldn’t be allowed in school and, as a result, I had to keep other needed groups out, then I would keep both out. But the Christian community should be working to make sure this dilemma does not arise.

But sometimes teachers and parents seem to be in an adversarial relationship. How should we as Christians work to affect change?

By involving ourselves with the normal parent groups. Parent-teacher problems escalate when we separate ourselves and form splinter groups that are usually perceived as targeting teachers.

What’s your perspective on the Christian school movement?

I have no ill feelings toward parents who send their kids to private or Christian schools. I am disturbed, however, by people in the Christian community who have ill feelings toward Christian parents who send their children to public schools.

To be perfectly honest, if I were flying from Washington to Miami, I wouldn’t be overly concerned about whether my pilot was a Christian or not. My concern would be can he fly the plane. I feel the same way about education. You do kids a disservice by not giving them the best education they can get to go with the Christian training they receive at home.

Unfortunately, most parents I’ve known have moved their children to private schools not because of curriculum considerations but because they want their children under tighter supervision. In other words, they want someone watching their children carefully. I can’t promise that in our school. In fact, that’s something we don’t even try to do.

It is a matter of faith for me as a parent of children in public school that the Lord is in control. If others think their kids need tighter boundaries, that’s a judgment they have to make. But I think behavior problems are the poorest reasons for sending a child to Christian school. We are fooling ourselves if we think kids are much different in the two schools. Kids are kids. They have the same fears and the same problems wherever they are.

As an educator and a parent, what kind of response have you had to your witness for Christ in the public school?

It is easy to wonder how much of an impact you have on people. One encouraging thing that came out of the hostage crisis1In November of 1982, Dr. Alwood and eight other school employees were held hostage for 21 hours by an armed, former student trying to negotiate a meeting with his girlfriend. All of the hostages were eventually released unharmed. Dr. Alwood stayed with the student until he surrendered himself to the police. for my wife and me was a new appreciation for how many people have gotten the message that God is real to us. One of my fellow hostages said, “You had something I didn’t. I saw that whatever the outcome, you could accept it.” My wife and I, she on the outside waiting and I on the inside, heard this over and over again. We were able to share with people how this “something” was available to everyone.

I think my relationship with Jamie, the gunman, during the time I was held hostage, is an example of the kind of forum a public school can be. If anyone thought that we spent 21 hours talking about the Lord, or that I had my Bible open the entire time, they would have been mistaken. It became apparent quite early that Jamie had some wacky theological ideas, and that pursuing spiritual issues with him might have meant a potential mental upset. Instead, we talked about his school days, which had been a pleasant experience for him.

Yet our time together was used mightily by the Lord. Christians all over Washington who knew that I was a Christian and that Jamie’s mother was also a Christian came together to pray for us. I was amazed at the number of Christian teachers who called me up afterwards to say, “I know where you stand, and I want you to know that I’m a Christian too.”

I came away knowing that God’s message doesn’t have to be preached from a pulpit to be heard.

Tim Stafford is a free-lance writer living in Santa Rosa, California. He is a distinguished contributor to several magazines. His latest book is Do You Sometimes Feel Like a Nobody? (Zondervan, 1980).