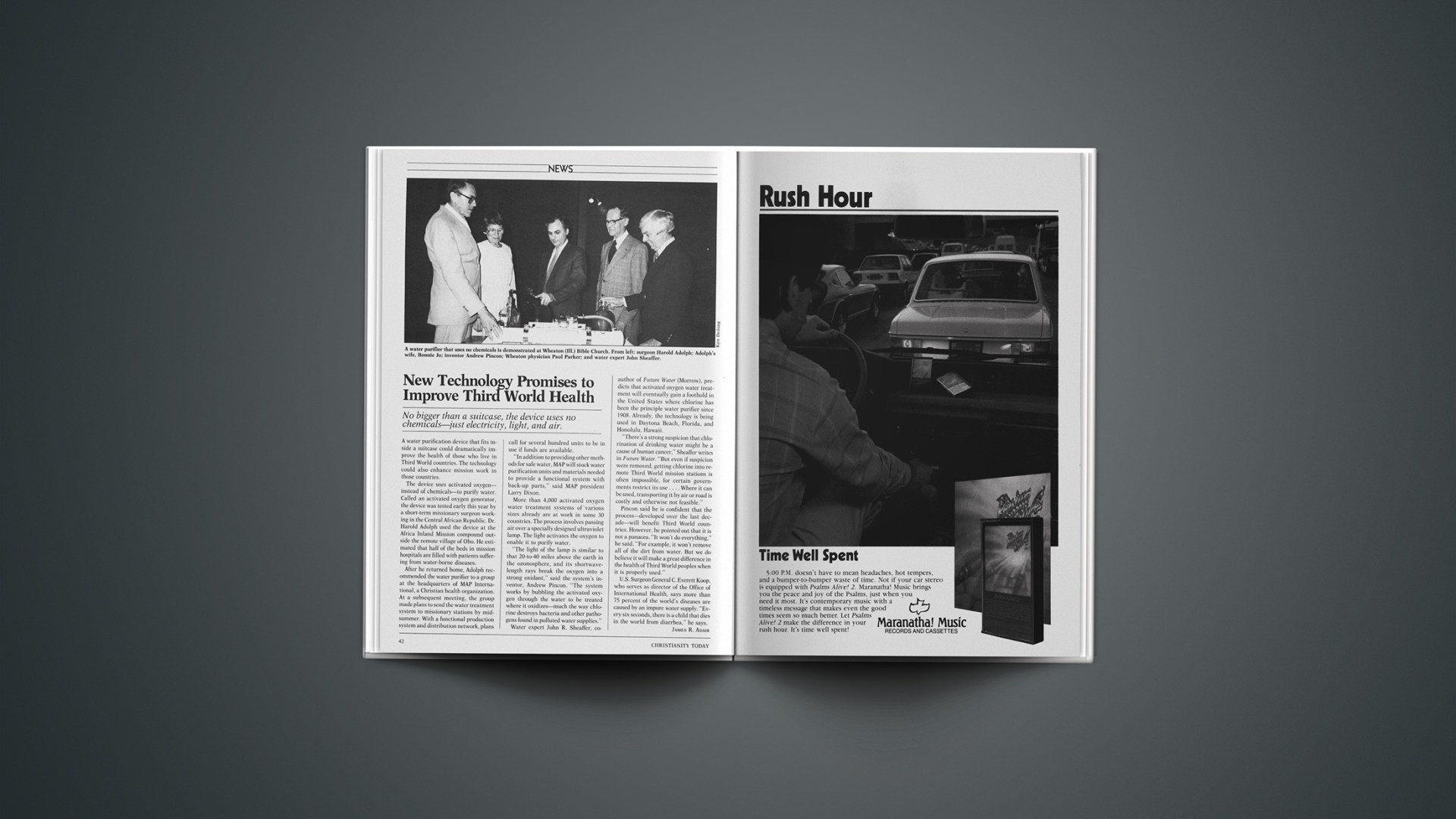

No bigger than a suitcase, the device uses no chemicals—just electricity, light, and air.

A water purification device that fits inside a suitcase could dramatically improve the health of those who live in Third World countries. The technology could also enhance mission work in those countries.

The device uses activated oxygen—instead of chemicals—to purify water. Called an activated oxygen generator, the device was tested early this year by a short-term missionary surgeon working in the Central African Republic. Dr. Harold Adolph used the device at the Africa Inland Mission compound outside the remote village of Obo. He estimated that half of the beds in mission hospitals are filled with patients suffering from water-borne diseases.

After he returned home, Adolph recommended the water purifier to a group at the headquarters of MAP International, a Christian health organization. At a subsequent meeting, the group made plans to send the water treatment system to missionary stations by midsummer. With a functional production system and distribution network, plans call for several hundred units to be in use if funds are available.

“In addition to providing other methods for safe water, MAP will stock water purification units and materials needed to provide a functional system with back-up parts,” said MAP president Larry Dixon.

More than 4,000 activated oxygen water treatment systems of various sizes already are at work in some 30 countries. The process involves passing air over a specially designed ultraviolet lamp. The light activates the oxygen to enable it to purify water.

“The light of the lamp is similar to that 20-to-40 miles above the earth in the ozonosphere, and its shortwave-length rays break the oxygen into a strong oxidant,” said the system’s inventor, Andrew Pincon. “The system works by bubbling the activated oxygen through the water to be treated where it oxidizes—much the way chlorine destroys bacteria and other pathogens found in polluted water supplies.”

Water expert John R. Sheaffer, coauthor of Future Water (Morrow), predicts that activated oxygen water treatment will eventually gain a foothold in the United States where chlorine has been the principle water purifier since 1908. Already, the technology is being used in Daytona Beach, Florida, and Honolulu, Hawaii.

“There’s a strong suspicion that chlorination of drinking water might be a cause of human cancer,” Sheaffer writes in Future Water. “But even if suspicion were removed, getting chlorine into remote Third World mission stations is often impossible, for certain governments restrict its use.… Where it can be used, transporting it by air or road is costly and otherwise not feasible.” Pincon said he is confident that the process—developed over the last decade—will benefit Third World countries. However, he pointed out that it is not a panacea. “It won’t do everything,” he said. “For example, it won’t remove all of the dirt from water. But we do believe it will make a great difference in the health of Third World peoples when it is properly used.”

U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, who serves as director of the Office of International Health, says more than 75 percent of the world’s diseases are caused by an impure water supply. “Every six seconds, there is a child that dies in the world from diarrhea,” he says.

Since the birth of Baby Jane Doe last October, government health officials have feuded with New York doctors over the release of the handicapped infant’s medical records. U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop sought the records to determine whether the infant, born with a spinal deformity, was a victim of discrimination when her parents and a doctor chose to withhold life-prolonging surgery.

The courts have consistently ruled against Koop’s request, and two recent decisions soundly reinforce the prohibition on government intervention. In Baby Jane Doe’s case, the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals refused a government request for a rehearing. The original ruling will stand unless it is overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court. At this writing, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has not decided whether it will appeal the case.

In another more sweeping decision, a federal district court struck down the Reagan administration’s revised Baby Doe regulations. They were the focus of a lawsuit brought by the American Medical Association (AMA) and five other medical groups (CT, April 20, 1984, p. 44).

The judge issued an injunction that applies nationwide, saying the government may not investigate treatment decisions affecting any handicapped newborn. Koop designed the original regulation, based on federal law prohibiting discrimination against handicapped individuals. It required hospitals that receive federal funds to install a “hotline” to Washington so cases of neglect could be reported and investigated.

That regulation fell victim to a court ruling last year, so Koop devised a compromise that included a provision the medical community deemed essential—infant care review committees at each hospital that would assess difficult cases one by one. A major pediatricians’ group agreed to this version, but the AMA remained aloof and took the matter to court.

Meanwhile, right-to-life groups are turning their attention to Congress, where the House of Representatives passed a bill that approaches the problem from a different angle. The legislation redefines child abuse to include cases in which medical care or food and water are withheld from newborns with handicaps or serious birth defects.

Similar legislation in the U.S. Senate enjoys broad, bipartisan support, including liberal senators Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) and Alan Cranston (D-Calif.) and conservatives Orrin Hatch (R-Utah), Jeremiah Denton (R-Ala.), and Don Nickles (R-Okla.). “We need a strong signal from Congress that handicapped kids deserve nondiscriminatory care,” said Jan Carroll, of the National Right to Life Committee. “It will be especially important when a Baby Doe case comes before the Supreme Court.”

Court decisions like the ones in New York carry wider applications for other civil rights cases, Carroll said. She cited institutions where mentally retarded people are housed. “How will the government get in there to find out what is happening?” she asks. “The AMA refuses to admit that a child has any rights apart from its parents. That is an untenable position.”

“Baby Jane Doe,” the young New Yorker at the center of this policy storm, belatedly received treatment for water on the brain, a condition that often accompanies the spinal deformity known as spina bifida. Keri-Lynn, the baby’s real first name, was growing stronger daily despite her health problems. Her parents arranged for an operation following a change of mind, and took Keri-Lynn home for the first time in April. Their identity remains anonymous.