On October 5, 1980, a Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper columnist set aside momentous matters of state elections, legislative debates, and military coups and announced, in print, the birth of his third child. “The struggle to reelect the 39th President, or to elect the 40th, though not insignificant, has been eclipsed by a far larger event, the birth of the 48th President: Victoria Louise Will.”

The birth, noted proud father George F. Will, drew questions from the older Will children. “[Victoria’s] two brothers, aged 8 and 6, have said ‘We are not amused’ that she chose to be born female.… I, in turn, have advised them of Stephen Leacock’s axiom: ‘The parent who could see his boy as he really is would shake his head and say, ‘Willie is no good; I’ll sell him.’ ”

It cannot be. Eight- and six-year-olds do not mutter with airy precociousness, “We are not amused,” upon the birth of little sisters. And fathers do not answer such unlikely remarks with droll axioms liable to make the boys think they are about to be abandoned. Then again, at the Will home, it might be.

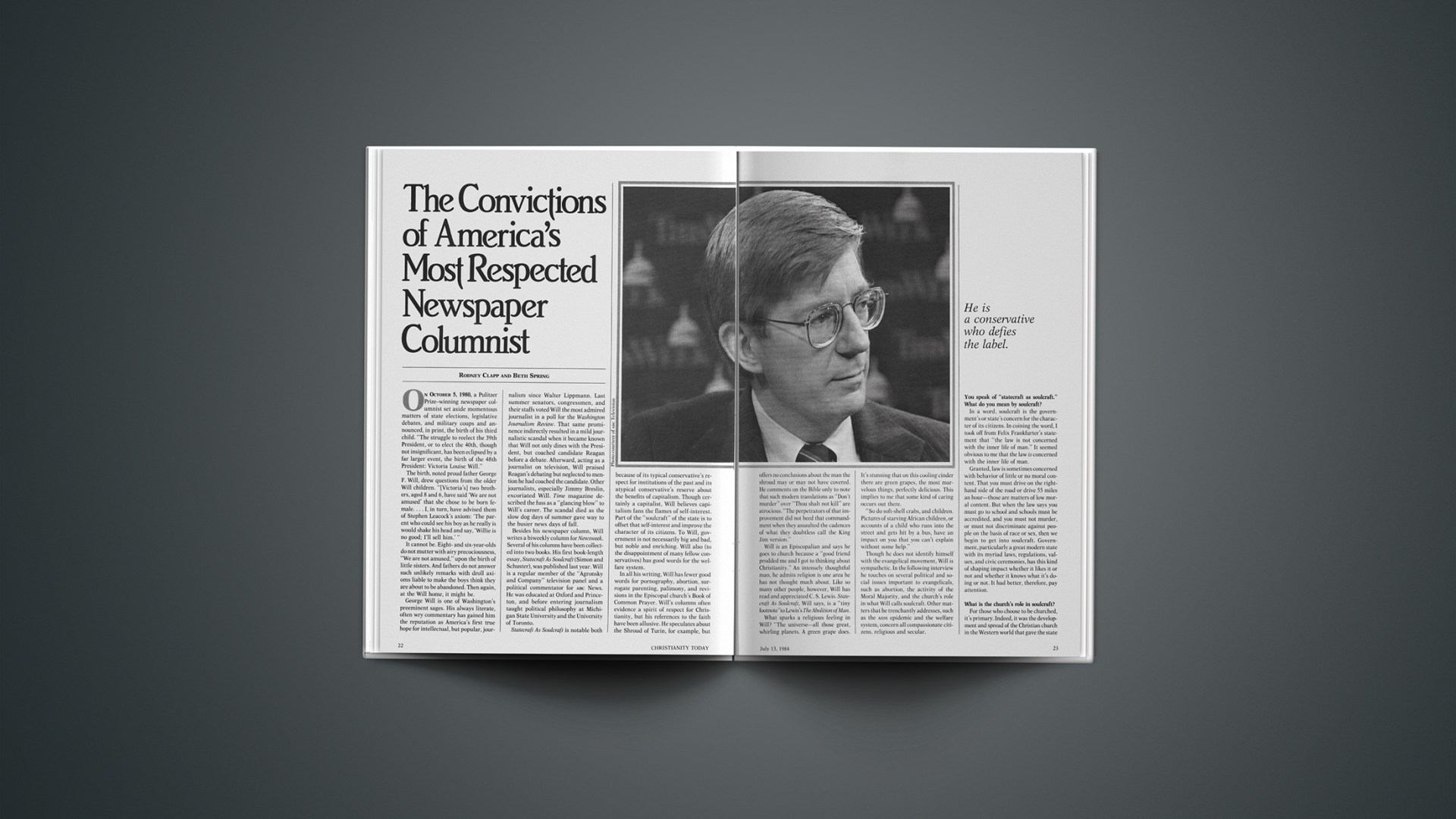

George Will is one of Washington’s preeminent sages. His always literate, often wry commentary has gained him the reputation as America’s first true hope for intellectual, but popular, journalism since Walter Lippmann. Last summer senators, congressmen, and their staffs voted Will the most admired journalist in a poll for the Washington Journalism Review. That same prominence indirectly resulted in a mild journalistic scandal when it became known that Will not only dines with the President, but coached candidate Reagan before a debate. Afterward, acting as a journalist on television, Will praised Reagan’s debating but neglected to mention he had coached the candidate. Other journalists, especially Jimmy Breslin, excoriated Will. Time magazine described the fuss as a “glancing blow” to Will’s career. The scandal died as the slow dog days of summer gave way to the busier news days of fall.

Besides his newspaper column, Will writes a biweekly column for Newsweek. Several of his columns have been collected into two books. His first book-length essay, Statecraft As Soulcraft (Simon and Schuster), was published last year. Will is a regular member of the “Agronsky and Company” television panel and a political commentator for ABC News. He was educated at Oxford and Princeton, and before entering journalism taught political philosophy at Michigan State University and the University of Toronto.

Statecraft As Soulcraft is notable both because of its typical conservative’s respect for institutions of the past and its atypical conservative’s reserve about the benefits of capitalism. Though certainly a capitalist, Will believes capitalism fans the flames of self-interest. Part of the “soulcraft” of the state is to offset that self-interest and improve the character of its citizens. To Will, government is not necessarily big and bad, but noble and enriching. Will also (to the disappointment of many fellow conservatives) has good words for the welfare system.

In all his writing, Will has fewer good words for pornography, abortion, surrogate parenting, palimony, and revisions in the Episcopal church’s Book of Common Prayer. Will’s columns often evidence a spirit of respect for Christianity, but his references to the faith have been allusive. He speculates about the Shroud of Turin, for example, but offers no conclusions about the man the shroud may or may not have covered. He comments on the Bible only to note that such modern translations as “Don’t murder” over “Thou shalt not kill” are atrocious. “The perpetrators of that improvement did not heed that commandment when they assaulted the cadences of what they doubtless call the King Jim version.”

Will is an Episcopalian and says he goes to church because a “good friend prodded me and I got to thinking about Christianity.” An intensely thoughtful man, he admits religion is one area he has not thought much about. Like so many other people, however, Will has read and appreciated C. S. Lewis. Statecraft As Soulcraft, Will says, is a “tiny footnote” to Lewis’s The Abolition of Man.

What sparks a religious feeling in Will? “The universe—all those great, whirling planets. A green grape does. It’s stunning that on this cooling cinder there are green grapes, the most marvelous things, perfectly delicious. This implies to me that some kind of caring occurs out there.

“So do soft-shell crabs, and children. Pictures of starving African children, or accounts of a child who runs into the street and gets hit by a bus, have an impact on you that you can’t explain without some help.”

Though he does not identify himself with the evangelical movement, Will is sympathetic. In the following interview he touches on several political and social issues important to evangelicals, such as abortion, the activity of the Moral Majority, and the church’s role in what Will calls soulcraft. Other matters that he trenchantly addresses, such as the AIDS epidemic and the welfare system, concern all compassionate citizens, religious and secular.

You speak of “statecraft as soulcraft.” What do you mean by soulcraft?

In a word, soulcraft is the government’s or state’s concern for the character of its citizens. In coining the word, I took off from Felix Frankfurter’s statement that “the law is not concerned with the inner life of man.” It seemed obvious to me that the law is concerned with the inner life of man.

Granted, law is sometimes concerned with behavior of little or no moral content. That you must drive on the right-hand side of the road or drive 55 miles an hour—those are matters of low moral content. But when the law says you must go to school and schools must be accredited, and you must not murder, or must not discriminate against people on the basis of race or sex, then we begin to get into soulcraft. Government, particularly a great modern state with its myriad laws, regulations, values, and civic ceremonies, has this kind of shaping impact whether it likes it or not and whether it knows what it’s doing or not. It had better, therefore, pay attention.

What is the church’s role in soulcraft?

For those who choose to be churched, it’s primary. Indeed, it was the development and spread of the Christian church in the Western world that gave the state the excuse that it could abdicate soulcraft. Before that the Greeks could say, “Athens worries about the souls of the citizens of Athens,” because there was simply no separation between civic and theistic concerns. In the later Western world, there was more or less a clear division of labor, however. That division of labor continues to this day. Because we have the First Amendment and the clear disestablishment of religion, we’re very apt to say that churches and families and voluntary civic organizations worry about the inner life, and the state maintains order and puts up traffic lights.

I’m saying you can’t expel the state from affecting soulcraft, especially when people say, with more or less disputable evidence, that this is an age of declining religious interest and rising secularism. But beyond that, we expect of the state a structure of laws and services that make it omnipresent and omniprovident. When the American government was small and rested so lightly on everyone, then you could say it was really irrelevant to this. It wasn’t, even then. When the First Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, it set aside lands for public schools. I think the defining, distinguishing characteristic of the United States is the care taken for public education from the word “go.” Even when the American state was a light and gossamer thing, it was intruding itself into this sphere, saying, “If you’re going to be citizens of the free society, that has certain prerequisites, and it is the civic authority’s responsibility to see to the civic prerequisites.”

Does the church inform the soulcraft that is done by the government? What is the proper relationship?

It depends on your concept of the church—whether, for example, your Christianity is primarily a vertical undertaking, a relationship between the individual and God, or whether it’s a social, horizontal enterprise. I suppose it’s a bit of both: If people establish a correct vertical relationship, it has consequences for their horizontal relations as well. I tend to Dean Inge’s view that Christianity is good news, not good advice. There is no such thing as Christian economics or, frankly, Christian nuclear policy. Obviously your thinking should be informed by your whole view of the world and the cosmos, but there’s something a little odd about manufacturing Christian electrical engineering along the way.

Naturally some Christians want government to do soulcraft their way. The New Right is one example. What do you think of its emergence?

I once wrote a column called, “Who Put Morality into Politics?” What I said was that the Moral Majority did not put abortion on the social agenda. Nine Supreme Court justices did that. The Moral Majority did not put homosexual rights on the political agenda—homosexual activists and militants did. The Moral Majority’s political agenda is not quite mine, but it’s legitimate. I am against people expelling other views and giving us a narrow and impoverished political agenda.

The right wing tends to do it by saying the allocation of wealth and opportunity is not politics, it’s economics: the market allocates wealth, so we won’t worry about it. Clearly we don’t believe that. We all respect the market, a marvelous allocator of wealth and opportunity, but that’s rough justice, and politics is to take the roughness out of it. Social security is a corrective of the market. All kinds of programs are.

On the other hand, the Left limits the political agenda, too. Once they won the abortion argument, proabortionists said, “Argument’s over.” From the start of this republic to 1973, abortion was a legitimate thing for the states to regulate. Then, through the assertion of judicial power, they got a certain abortion law in, and now they say you can’t talk about it anymore. Of course you can talk about it. You can talk about it ceaselessly as modern medicine demonstrates the fecklessness of the 1973 opinion.

Another example: homosexual rights. If the proper attitude toward this kind of social and sexual behavior is not a legitimate topic for social argument, what in the world is—soybean subsidies? It’s cuckoo to say that the state can be concerned with nurturing soybeans and not virtue.

You’ve written that the New Right’s involvement in politics need not be less, but better. How can it be better?

Left, Right, or center, politically involved people need to hear political arguments in a new way. They need to hear a deeper resonance when they hear those arguments and ask, “This social policy fits into a general concern with nurturing what? What are we after? What kind of people are we apt to be if we take this approach?”

I’m against prayer in school, for instance. We need a clearer idea of prayer than some of these people have. I don’t think prayer in school is unconstitutional. It’s perfectly constitutional, but that’s a separate argument. As a policy, voluntary school prayer can’t be voluntary and it can’t be prayer.

Or take abortion and the New Right. We now have 1.6 million abortions a year. It is the most common surgical procedure in the country, more common than tonsilectomies and appendectomies. Things change when you get that many abortions. You cannot just turn around and say, “We’re going to outlaw it today.” You must conduct a very sophisticated, long-term argument built around something like the Hatch Amendment, which simply says states can regulate abortion. All the Hatch Amendment would do is start 50 arguments: one in each state. We already have 50 arguments anyway. This would localize them and begin the change. It would be very good for the country. But it’s a process of long-term education and requires what has been called the patience of politics. Politics is not for the impetuous.

And yet there are a lot of impetuous people in politics.

True. Politics is a passionate activity. It attracts the passionate. It ought to. You don’t want lukewarm, political mechanics, you want people with convictions, passion. That’s the drama of politics, and it tends to bring too much passion to the surface. The stakes are high. Politics is a very adult business, and it doesn’t always bring out the adult in people. But I’m not one who attacks politicians. There are never more than 537 sent to Washington by the people. There are some rogues and some saints, and a lot in between. But by and large, the 537 are more public spirited and more serious than the people who sent them here.

How should religious faith affect a politician’s official conduct?

The fundamental religious view, spanning Judeo-Christian tradition, is that human beings thirst for something larger than their appetites, something more lasting and certain. That’s why some people go to church; that’s why some people go into civic activity. They want to be a part of something larger than themselves. Politics is one way of expressing this. If it were really just a cafeteria serving various appetites, brokering this group against another to satisfy as many demands as possible, I don’t think serious people would want to devote a life to it.

What about the individual politician who has religious convictions? How should those convictions come into play in expediting his duties?

In the same way that the convictions of an Aristotelian of no particular religious interest could come into play. Someone could say, “Aristotle’s ethics provide a powerful, convincing view of the good person and the good society, a clear picture of how creatures of our nature should live, and I’d like to try to approximate that.” It doesn’t have to be a transcendental religious view.

So a person’s religious faith might give him a general idea of what he would like society to be, and then help him to work in that direction?

Yes. A religious view gives you a sense of what the better angels of our nature are—Lincoln’s phrase. It convinces you there are better angels. If you have an absolutely bleak view of human nature, which seems incompatible with a religious view properly understood, then politics would really be a grim undertaking. If people are just awful and they stay awful and it’s nothing but keeping order, who wants to do it?

You mentioned abortion and your preference for the Hatch Amendment. You would work to ban abortion gradually but surely?

I would not absolutely ban abortion. Suppose you know a fetus has Tay Sachs disease, which I gather means certain, slow, painful death. There is suffering to the child, suffering to the parents. I’m not tough enough to require that. I wrote that, by the way, in a column long ago and no one ever noticed.

Then you would leave abortion up to the individual states—whatever each decided?

Yes. States ought to be able to regulate abortion. What some people in the right-to-life movement say—and they’re quite right—is that California and New York will have abortion on demand and that will be good for the airlines. That’s the price you pay for federalism. It would be a bit like divorce was historically. Nevada said, “We don’t have anything. The Comstock Lode is exhausted, we’re out of water and can’t grow anything. What will we have? How about divorce?” Easy divorce went from Indiana to one of the Dakotas to Nevada. It became the divorce state, and got gambling to entertain the people while they were waiting for divorces. Federalism, for better or for worse, produces that kind of competition.

Let’s consider pornography, an inelegant topic you’ve written about eloquently. Here the domino theory or slippery slope argument that conservatives are so fond of is turned against them. Advocates of pornography say that if certain books are banned, all others will be endangered. Can there be a responsible control of pornography? Or does one domino, one book, fall after the other? Is the first step down the slippery slope also the last?

Life is lived on a slippery slope. It’s nothing but drawing lines that are hard to draw. It’s not like tennis, with boundaries that indicate this ball is in and that one was out. Having a police force is dangerous: it could become a gestapo. Taxation is dangerous: it could become confiscation.

The most damaging thing to our society isn’t pornography. It is the argument that has been used to justify tolerating it—the argument that all critical standards are inherently capricious and arbitrary. “One man’s Shakespeare is another man’s trash.” If you say that, you’re saying people are fools, they’re not fit for self-government. If people are really incapable of making determinations between a masterpiece and garbage, then what hope is there that they can make their own laws? It’s a demoralizing view of the capacities of the populace.

You speak of “conservatism with a kindly face.” How would conservatism with a kindly face deal with the AIDS epidemic, especially as it affects homosexuals?

That’s a public health problem, and public health is public business. I have written that practicing homosexuality is an injury to normal functioning, that it’s not just another preference. That doesn’t mean that homosexuals are pariahs of any sort. They are citizens, human beings. Their homosexuality shouldn’t complicate your normal duty to love them as neighbors.

We used your phrase “conservatism with a kindly face” to refer to the AIDS epidemic. But in your writing you mention it in arguing for the welfare state. Judging from reactions in the National Review, you are not persuading some conservative friends. Are you making any inroads?

Yes, because I have on my side the fact that people have no choice but to agree with me in the end. The welfare state is as much here as the Washington Monument. It is a fact of our political terrain, and of the political terrain in every developed industrial society. People want to buy certain things collectively. What you argue about is what and how much.

Does anyone really want to argue that the world is worse off because we have social security? Thirty years ago a lot of nice, sincere, reflective conservatives thought that. They were convinced that the fundamental turn under Roosevelt changed for the worse the relationship of the citizen to the state. I disagree, and I think most Americans would now.

I have three children growing up in Chevy Chase. There are children growing up 10 miles away in Anacostia [a poverty-striken neighborhood in Washington, D.C.]. They’re all Americans, the children of Chevy Chase and Anacostia, but they have almost no common experience. That’s worrisome, and it ought to be especially worrisome to a conservative because conservatives are nationalists. They say we all ought to be Americans, to share certain values, and to feel positive about the community. But what does my child have to say to the child in the slum? It’s very hard.

What is the solution?

I don’t know. But whatever it is, it isn’t to deny the problem. That is why I make such a thing about equality of opportunity. Conservatives are right, but they are caught by their own commitment to take seriously just how complicated equality of opportunity is. In fact, equality of opportunity is a government product. It is not natural. You cannot say that just by being born we’ll all have equality of opportunity. In that case, it would be foolish to be born in Anacostia. How silly of them! They should have been born in Chevy Chase.

A final question: You write often from the perspective of a parent. Obviously parents perform soulcraft on their children. Yet some parents now say they don’t want to indoctrinate religious beliefs in their children, that children should choose for themselves. Is that proper parental soulcraft?

No. If you believe you have found a religious tradition that is true and good and useful, you are not doing your child a favor by not exposing the child to it. Not any more of a favor than if you say you have found certain healthy habits, like brushing your teeth, but “he’ll find that out on his own.” If you’re going to worry about the enamel of his teeth, the strength of his or her muscles, you might worry about the inner life as well.

Tim Stafford is a free-lance writer living in Santa Rosa, California. He is a distinguished contributor to several magazines. His latest book is Do You Sometimes Feel Like a Nobody? (Zondervan, 1980).