“I can go just about anywhere, and I never have to worry,” says a robed and hooded man. “If I get in trouble, I can make one phone call, and immediately I’ll get help.… People, guns, anything I want. I could even get a tank if I wanted. But I haven’t needed that yet.”

“When do they burn the cross?” he is asked.

“We don’t burn crosses, we light them,” he clarifies. “We light the cross because Christ is the Light of the world.”

From a makeshift stage in the middle of an Alabama hillside, a local band blares country and rock tunes as white-robed and hooded figures stroll about, laughing and talking informally. Many of the men have brought their families. Proud mothers pull out their pocket Instamatics® to grab a snapshot of Daddy, all decked out in white, holding Junior. Some of the mothers themselves wear robes and hoods. Other families man the refreshment stand, selling hot dogs, hamburgers, and RC Cola. (No beer or liquor is permitted.)

In a nearby booth, a bearded man in a KKK baseball cap displays Klan belts, buckles, bumper stickers, hats, wallets, knives, and helium-filled KKK balloons for the kids. Quite a few teenagers and college students roam through the crowd, some clad in white, others in jeans and plaid flannel shirts.

Strings of bare bulbs, not yet lit, surround the gathering. And beyond the lights, off to the far side of the field, stands a cross, wrapped in burlap and soaked in diesel fuel. It seemingly goes unnoticed by all but a few third-graders, who play touch football in its lengthening shadow.

The air is quickly cooling from afternoon temperatures in the 70s. Dusk has settled in, and darkness is about an hour away. The crowd numbers three or four hundred at most (a disappointing turnout, someone said), about half robed and hooded, and the other half families, friendly supporters, and a few curious observers—all white, of course. Everyone whoops and cheers as the band finishes its final song. Then a Ku Klux-clad announcer officially welcomes the crowd, and turns the mike over to a graying woman who opens the program with prayer. She too is dressed in white, her pointed hat tipped backward in feminine fashion. She prays with startling sincerity, calling out to Jesus prayer-meeting style.

“And Jesus,” she says, her voice barely audible above the buzzing sound system, “you know our needs … you know our feelings about the Klan.… And Jesus, you know how much it hurts us when we hear people say you can’t live right and join the Klan. Jesus, I try to live right, and I want to do your will.…”

Background

The Ku Klux Klan (from the Greek kuklos, meaning circle or wheel) arose in the aftermath of the Civil War, but not until after the release of D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film, The Birth of a Nation, did the movement gain widespread support. The film romanticized the Klan and fueled racial fears so that by the mid-1920s, KKK membership had peaked at nearly 5 million members. For the next 50 years the Klan would influence (and sometimes dominate) the American political scene. Their activities were often violent in nature—lynchings, murders, bombings. By the 1960s and ’70s, many members had gone underground, many had quit, and a few had remained. Splits and rivalries occurred among various Klan factions.

According to the Klanwatch Project of the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama, about 25 different Klan groups have operated within the past five years or still do so. The three largest of these, respectively, are the United Klans of America, based in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and headed by Robert Shelton; The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, based in Tuscumbia, Alabama, and officially headed by Don Black, who is currently in jail; and the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, based in Denham Springs, Louisiana, and headed by Bill Wilkinson.

Klanwatch estimates that the present combined national membership of all 25 public Klan groups amounts to less than 10,000. According to Klanwatch, virtually all of the groups state that theirs is a Christian calling to separate and/or eradicate all minority races to preserve and protect the purity of the white (Aryan) race.

An Evening Of Hatred

Today is Saturday, October 15. This afternoon about 100 KKK (Invisible Empire) members from several communities in Alabama and Georgia assembled at Handley High School, donned their white apparel, and marched for a mile through the center of Roanoke, Alabama, ending at the front porch of city hall. Imperial Wizard Bill Wilkinson led the march and spoke from the city hall steps. He stressed political and legislative changes that would protect whites and remove special treatment for minorities. He never used the word “nigger” or any other derogatory names or terms. He spoke with force and authority, and passionately set forth the official goals and purposes of the Klan: voluntary separation of the races, and the protection and preservation of the white race.

Unfortunately, the toned-down, politically oriented speeches given in front of city hall this afternoon turn to high-powered, endless tirades against “niggers” for this evening’s rally. As various speakers take their turns, nothing approaches the sincerity of the woman’s opening prayer. For example:

“Sure is nice to see all you white folks here. And it’s great that we don’t have to rub elbows with any niggers!” “Ronald Reagan may not be a racist, but I’ll bet he doesn’t have any black jelly beans in his jar!”

“I’m an electrician, and I know that when you mix a black wire and a white wire, you get sparks. It’s the same with black people and white people. They’re not meant to be mixed together!”

Again, Wilkinson gives the main address; and though he still emphasizes political and legislative issues, he speaks in a much louder, more antagonistic manner than this afternoon. His approach is generally intellectual, argumentative, rational rather than purely emotional. He speaks smoothly, with authority, and like a politician he pauses every few phrases for applause.

Complete darkness has now settled over the countryside, bringing with it a slight chill and a thin layer of fog. The hanging bare bulbs now burn brightly through the mist, casting an eerie glow over the gathering.

More speeches drag on, and they begin to sound the same. But the announcer rekindles the audience’s attention by introducing a 15-year-old girl. The crowd whoops and cheers and claps as a short, sandy-haired girl climbs up on the platform.

“Hey y’all,” she says. “I’m kinda little bit nervous; it’s the first time I’ve gotten up in front of this many people in my life! Plus it’s the first rally I’ve ever been to. Like he said, my name is Cheryl Hoffman [not her real name]. I’m 15 years old, I’m a member of the Klan Youth Corps and I’m proud of it.”

More cheers. “I attend a high school which is about 90 percent black. I tell you, we’ve got so many niggers you could make a Tarzan movie—except it would be hard to find a white person to be Tarzan.

“Well, I’m here today to tell you all about the kind of harassment I’m put through at school. Like in the mornings, sometimes I have to go down this super-long hall to get to my locker. Lined up against the wall are about 30 nigger boys. When I go down there I have to put up with rude, nasty, disgusting nigger boys and their vulgar comments. I even have to put up with them reaching and trying to grab me.”

Cheryl goes on to complain about Black History Month at school: “I’m forced to study about a bunch of niggers that don’t pertain nothin’ to me!”

Then she launches into a tirade against atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair: “That’s the lady who banned public prayers from schools. I think she’s nothing but a female dog, a flea-bitten female dog! And now she’s trying to cut [prayer] out from our airways and our televisions, and keep us from learning about our Lord. I tell you, I’m a devout Christian, I go to church and I love the Lord and I’m proud of it. You know I’d love to lead prayer in school, but I can’t because of her. The only way we can stop her and all these communist niggers out there is to join the Ku Klux Klan.

More hollering. “We need to join together because the KKK stands for three main things,” Cheryl concludes. “We all know that Number One is God. We stand for God, and want to teach all people about the Lord. Two is for Race, which is the white race—and we all know, the right race!” Again the audience erupts into cheering and applause.

“And Number Three is Country, to help make America what it once was. The only way we can do that is to join the KKK. We need your support, y’all.”

The crowd claps and whoops like crazy as Cheryl hops down from the stage. She is greeted by her white-robed father, who envelops her with a giant embrace. Then her mother and younger brothers and sisters, beaming with pride, also surround her with hugs. Smiling broadly, Cheryl stands with her family and applauds the next speaker.

The final speaker concludes by explaining the dilemma their leader Bill Wilkinson is in. Bill and the KKK have been sued by several groups for alleged illegal activities (most notably the operation of military-style training camps for young people). And the cost of defending these charges in court has considerably drained the central office’s finances.

The speaker asks people to come to the front and drop their donations into white plastic buckets alongside the platform. His plea sounds just like the invitation to come forward at the end of a Sunday sermon. Slowly and quietly, people begin filing to the front, mostly white-robed people.

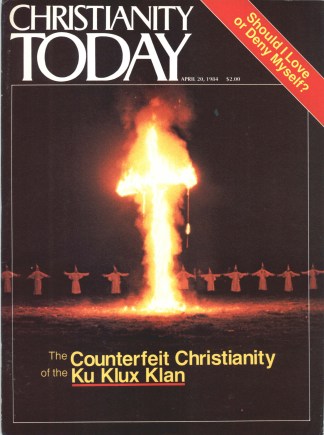

Now it is time for the cross lighting, and the crowd makes its way to the far side of the field. One by one, the robed Klanspeople light their torches (which look like broomsticks with rags) and encircle the cross. They widen the circle, pushing back the crowd, while Bill Wilkinson stands near the center with a bullhorn. He takes a moment to say that the cross lighting is a Christian and a sacred ceremony, not a display of hatred or violence. Then he issues orders to the participants in simplified military fashion.

At his command, they march around the cross, then stop, face the center, and wave their torches up and down three times. Then they circle in the other direction, stop, and wave again. Finally Wilkinson says: “Klansmen—to the cross.” The ring of white figures closes in, and the torches are tossed at the foot of the cross.

The flames quickly travel to the top and then to each side of the cross. For the first minute or so it is engulfed in fire, but then the initial flare-up settles down and the cross’s shape stands out clearly. The circle of white robes has reformed, and everyone is silent.

“Klansmen—salute!” commands Wilkinson. They all stretch their arms to the side while Wilkinson recites a litany of some kind: “This cross is an inspiration, a sign of the Christian religion, a symbol of faith, hope, and love. We do not burn, but rather light the cross to signify that Christ is the light of the world, and that his light destroys darkness. Fire purifies gold, silver and precious stones. It destroys wood, stubble, and hay.…

As Wilkinson speaks, a man stands nearby holding his wide-eyed two- or three-year-old daughter. “Daddy, look!” she says.

Dad makes no effort to prevent her from watching. “That’s a cross,” he says to her softly. “See that cross?”

“It’s burning!” she exclaims gleefully, as if playing a guessing game.

“Yeah,” Dad confirms. “See it on fire?… That’s white power!” He gives her a fatherly squeeze as they gaze upon the scene.

Kkk “Theology”

Just what does the Ku Klux Klan believe? That’s hard to say, since no unified theology characterizes all Klan factions, and many members are uneducated, secular citizens. But Klan leaders and more educated members have attempted to Christianize their prejudices by appealing to various biblical passages.

One of these views, based on the account of Noah and his three sons in Genesis 9:20–27, erroneously assumes that Ham was a Negro and Noah’s curse of him therefore extended to the entire Negro race.

Another prevalent view is that Eve had sexual intercourse with Satan in the Garden of Eden and bore Cain. (Abel was her child by Adam.) Cain is identified as the seed of the serpent in Genesis 3:15, and the Jewish race descended from him. According to Klan teaching, the Jews then fled to the woods, where they had sex with the animals and created all the other minority groups. Jews and minorities are viewed as clearly inferior to the true chosen people, the white race, descended from Adam.

But wasn’t Jesus a Jew? Klan doctrine neatly skirts this problem by saying Jesus descended from Adam and is therefore part of the white, Aryan race.

A closer look at Scripture will quickly expose the fallacies of Klan theology. According to Genesis 3, Eve’s sinful act was not sex with Satan, but the eating of the forbidden fruit. Genesis 4:1–2clearly states that both Cain and Abel were children of Adam and Eve, making it impossible for them to have begun different races. Abraham, not Cain, is identified as the father of the Jewish race (Gen. 12:1–3; Rom. 4).

While the Klan distinguishes between the Jews (who they say descended from Cain) and the Israelites (who they say descended from Adam), the Bible plainly equates the two. In Romans 9, the apostle Paul distinguishes between the physical and spiritual descendants of Abraham, but the distinction is based completely on God’s election and man’s faith, not on racial differences.

Though God commanded the Jews in the Old Testament to remain racially pure, his primary concern was for their spiritual purity. God in no way limits his promises or blessings to the Jews but rather tells Abraham that “all the nations of the earth shall bless themselves by him” (Gen. 18:18).

Regarding the Jewishness of Jesus: Once the Klan’s distinction between the Jews and Israelites is disproved, no argument can be set forth to depict Jesus as anything but a bona fide Jew. The genealogies of Matthew and Luke show his lineage through both Abraham and Adam. Jesus’ minority status becomes the Klan’s biggest embarrassment.

Somehow the KKK seems to ignore two themes that recur throughout Scripture: that God makes salvation available to all peoples, and that in God’s eyes all people are equal. The universality of the gospel, predicted in the Old Testament (Joel 2:28–32; Isa. 42:6, 52:10, et al), becomes one of the central messages of the New. The Book of Acts describes the growing awareness of the young, Jewish church that God also wants the gospel preached to the Gentiles—people of different races and cultures. This awareness grew through the speaking in other languages at Pentecost, the subsequent conversion and ministry of non-Jews, and Peter’s sheet vision at Joppa after which he concluded, “Truly I perceive that God shows no partiality, but in every nation any one who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him” (Acts 10:34–35).

The apostle Paul echoes Peter’s conclusion throughout his own writings; in fact, he even calls himself an “apostle to the Gentiles” (Rom. 11:13). “For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek,” he writes. “The same Lord is Lord of all and bestows his riches upon all who call upon him” (Rom. 10:12; see also Gal. 3:26–29). The biblical principles of universality and equality cut to the very heart of Klan doctrine, making it completely incompatible with true Christianity.

“Different branches of the Klan have different philosophies,” says recent Christian convert Tommy Rollins, former Grand Wizard of a Klan group known as the White Knights of America. “But the bottom line is always the same: the white race is God’s chosen people, and the minorities were placed here by Satan to overthrow. That’s how the organization can justify killing, terrorizing, and so on, because these other people are not looked upon as being human.”

“Just Kinda Neutral”

Following the cross lighting, the crowd lets forth one last round of cheers and applause, then disperses. The eerie atmosphere of the ceremony quickly changes to that of a homecoming bonfire. The band steps onto the stage and begins another set. Many decide to remain and listen to the music or chat with friends. Others stand near the cross, which still burns but much less brightly. They rub their hands together near the flames for warmth, as if the cross were a campfire.

One friendly 16-year-old boy strikes up a conversation. He says he and his parents attend a local Baptist church (his parents are both active in the Klan). And others in the church know of the family’s Klan involvement.

What do people from church say to his parents? “No one really talks about it. Besides, some of the others at church are involved [in the KKK] too. The people around here who join the Klan just join—it doesn’t have nothing to do with their religion.”

And how does the preacher feel about this? “He doesn’t preach about it, but he has talked to my parents. He doesn’t really support them, but he doesn’t have nothing against ’em to say. He’s just kinda neutral about it.”

Local Pastors’ Views

How any preacher could be neutral on a subject such as the Klan is a mystery. But several Roanoke-area pastors, two blacks and two whites, talked about the KKK and the October rally. All four condemn the Klan’s organization and activities, though rarely from the pulpit. (They prefer to preach against racist and terrorist groups in general, rather than by name.) And none of them has ever been a victim of Klan harrassment. But they differ somewhat on how the church should respond to the Klan.

“I think the attitude toward the resurgence of the Klan in Roanoke is one of complacency, especially on the part of the church,” says Lithonia J. Wright, a Roanoke resident and pastor of New Home Missionary Baptist Church in Hissop, Alabama. “Even some black churchmen, along with my white brothers, have been too silent.”

Wright recommended that the Randolph County Ministerial Association publish a letter in the local newspapers opposing the Klan. Last fall the association talked about the issue just before the KKK rally, but no official action or public statement was adopted, Wright says. “I think this complacency on the part of the ministers causes the lay people in the area to be quiet.”

“When the church fails to be the militant church that Jesus has established, [when it fails] to address all evils—personal sins and sins of society—and when we become so complacent that we don’t want to get involved, it’s advantageous to the enemy,” he says.

While completely agreeing with Wright’s opposition to the Klan, Steve Pearson, pastor of the First Church of God (Anderson, Ind.), a white congregation in Roanoke, explains his approach: “Our strategy was simply to boycott the march, to not even show interest in it. We [in the ministerial group] all promised to go back to our churches and say we felt strongly that this thing should not only be avoided, but totally ignored. We thought it would be nice if the downtown area [where the march took place] would be just like a graveyard—no one there, no interest whatsoever. And I think we did manage to keep a lot of people away from the meetings. Just standing there watching is almost like supporting them—or at least they think so. They want to be seen. So we just tried to avoid any kind of confrontation or visible support.”

Center Chapel Baptist Church (independent) stands two miles up the same road where the evening rally was held. That same night the church sponsored a big youth gathering. Pastor Mark Poston says the kids didn’t talk a whole lot about what was happening, but offered a few comments such as, “Down the road they’re burning the cross, and up here we’re lifting up the cross.”

While stressing the importance of the prejudice issue and opposing the KKK at every point, particularly its anti-Semitism, Poston doesn’t see the Klan as something that affects the everyday lives of his members. “I don’t preach a series of messages on the Klan as long as my people don’t feel it’s a real issue.”

Instead, he opts for strengthening the local church, and providing teaching that will help people discern counterfeit Christian groups. “Basically, the people need to be taught against any secret organizations, or against organizations that substitute for the work of the church,” he says.

Robert L. Heflin, pastor of Mount Pisgah Missionary Baptist Church in Roanoke, agrees with Wright’s remarks about the church’s complacency. But he also challenges the black people to oppose the Klan publicly in simple ways: “One thing would be to register and vote. That would be one of the most powerful weapons I know of—good citizenship. We need to take responsibility for our opportunities. I think that’s a sharp comment on us [blacks]; for all the opportunity we get, we don’t show a lot of responsibility as citizens. We don’t participate in civil activities enough.”

Counterfeit

In conclusion, three points about Christianity and the Ku Klux Klan merit restating:

1. The “Christianity” taught and adhered to by the KKK is indeed a counterfeit. It is based on clearly erroneous interpretations of Scripture. It manipulates the Bible into condoning principles that are entirely consistent with those of Nazi Germany: the superiority and purity of the white race, the need to separate from other inferior races, and ultimately the elimination of minorities. And it ignores two of the central themes of the New Testament—that the gospel is intended for all people, the Jew and the Greek, and that in God’s eyes all people are equal before him.

2. For many of its members, the Klan has served as a substitute for the church. Over and over again, Klan members mentioned togetherness, “fellowship,” and support as reasons for joining. The church can offer all this and more, and needs to consider how it can present the gospel of love in a way that will overcome the ignorance and fear held by so many Klanspeople. Is it possible that some have turned to the Klan because churches did not meet these needs?

3. Many churches have remained silent in the face of racial injustice and violence. Particularly in areas where the Klan is active or where other forms of discrimination abound, churches or Christian organizations must publicly, corporately, and peacefully oppose racism and terrorism, while aggressively setting forth the true biblical alternative.

VERNE BECKER