He forged a new concept of marriage and the family.

When his daughter magdalena died, Martin Luther’s reaction was surprising, yet strange. He knew God had blessed him, but he could not be grateful. “How strange it is,” he said, “to know that she is at peace and all is well, and yet to be so sorrowful!”

Luther appears to have been puzzled at his inability to put aside the “natural” human sorrow at the death of a child. At the same time we are struck by the fact that he believed he should be able to put his feelings aside. The explanation for this apparent anomaly lies in the fact that Luther was influential in creating a new set of attitudes and ideals about marriage and the family. Although he was to a very great degree the creator of these new attitudes, their very novelty caused him to be unsure of his own feelings at times.

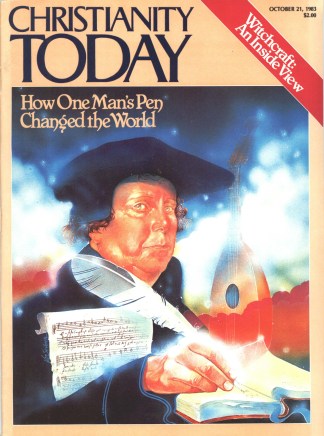

As a young man, Luther’s views had been shaped by a medieval formulation much different from the one he developed later in life. He had, of course, begun his career as an Augustinian monk, sworn to a life of celibacy, free from the cares and worldly concerns of family life. Twenty-five years before 14-year-old Magdalena died, Luther had been a celibate monk with no thoughts of family or children for himself. In ultimately rejecting celibacy for the clergy he not only set in motion a revolution in his own life but one for the Western world as well.

To understand the depths of the revolution, we need to know something about medieval attitudes toward marriage, sexual relations, and the family. While the material on these attitudes is rich and complex, manuals for confessors composed in the late Middle Ages provide some striking illustrations. In these manuals, sexual relations in marriage were usually considered to be at best a concession to the weakness of the flesh and were often categorized as venial sin. Part of the reason for this attitude toward sexual relations in marriage was that celibacy was exalted as the ideal. Marital sexual relations were often viewed with suspicion. The manuals frequently refer to a memorable line often (though incorrectly) attributed to Saint Jerome: “Anyone who is too passionate a lover with his own wife is himself an adulterer.” Indeed, marital relations were viewed with so much distrust that many clerics felt it was easier to avoid unchastity in a celibate life than in marriage. While these comments refer only to the sexual side of marriage, they indicate the medieval church’s attitude to marriage in general.

Luther changed traditional views of marriage. No wonder Magdalena’s death affected him so deeply. The change can best be demonstrated by an analysis of Luther’s views of marriage and celibacy. His exaltation of married life and rejection of celibacy are at the heart of what he saw as the most intimate of human relationships, those between husbands and wives, and parents and children.

In the course of his life, Luther wrote and spoke a good deal about marriage. Some of his comments appear in the context of his exegetical works. In his professional, professorial position at the University of Wittenberg, he lectured on the Bible and often touched on marriage. He also wrote tracts in response to specific questions about marriage. By the end of his life, he had formulated a consistent view of marriage and the family and the relationships they produce.

Luther placed the home at the center of the universe. In his scheme of things, God had established three essential institutions: marriage, the ministry of the Word, and secular government. Marriage, established by God in the Garden of Eden, preceded the other two in both chronological order and significance. Marriage is both a worldly order and a social calling. It is the highest such calling, because its place and its structure were established directly by God.

Luther’s doctrine of vocation also led him to exalt marriage. In the medieval church, the only calling was to a religious life. Luther held that any honorable occupation should be considered a vocation.

Responsibilities Of Husbands And Wives

Because marriage occupied such a significant place in Luther’s thought, he established norms for proper conduct of the members of the family in the Christian home. What Luther said about husbands and wives is not particularly remarkable. Husbands are to be providers. God said they were to work to support their families. Wives are to be submissive to their husbands and be their helpmates. At the same time, Luther recognized that there was more to marriage than this. Husband and wife are to live together not only in peace but also in happiness. There should be “pleasure, love, and happiness” without end in marriage. Husbands and wives should love each other with a devoted intensity. Love in marriage, Luther said, “burns as a fire and seeks nothing more than the conjugal spouse.…” He was speaking from personal experience. Seventeen years before Magdalena’s death he had married Katherine von Bora, a former nun.

Together, husband and wife had an obligation to bear children. Luther suggested at one point that couples should marry young—when the bride was no older than 15 or 18 and the groom no more than 20. He encouraged such early marriages because he believed they would produce more children. For those who might have worried about supporting a large family, he offered the perhaps facile assurance that if “God makes children, he will also support them.” Luther did not believe, however, that it was enough simply to produce children. They had to be trained and educated in a godly way as well.

Responsibilities Of Parents

Parents often had superficially disagreeable tasks. Diapers had to be changed and dirty faces washed. Parents had to quiet children’s fears and settle their quarrels; they became out of sorts and disagreeable. They cried and whined. They could be obstinate and stubborn. They were constantly demanding. Their parents were often harried, with little time to call their own. Luther advised parents, though, that there was more to their calling than these minor difficulties. Children are a gift and blessing from God. The true Christian, Luther said, recognizes that he is not even worthy to cradle a child or wash its diapers. God gave him the great opportunity to do so.

Luther believed that when children reached the age to be married, their parents should assist them in finding a spouse. Parents had to walk a careful line, however. The duty to help one’s child find a mate was part of being a parent. Parents who did not do so abdicated their responsibility as parents. On the other hand, parents did not have the right to force their offspring into a marriage the young people did not want. A parent who forced a child into such a match acted contrary to God’s will and to nature, becoming virtually a murderer of the child. But children should be willing to take their righteous parents’ guidance and follow their direction in the choice of a spouse, too.

Luther condemned parents who intervened in their children’s marital plans for crass economic or social reasons. He also condemned an even greater evil—celibacy. Luther allowed parents the right to forbid a child to marry a specific individual, but he firmly maintained that they could not legitimately deny marriage in general. God had created all of his children for various functions, including procreation. By forbidding marriage, parents interfered with this divine work.

Luther On Extramarital Sex

Luther also wanted to preserve the moral character of marriage. It is a way to avoid sin. Luther’s position on extramarital sexual relations is clear and unambiguous. He believes that premarital sexual relations, even between intended spouses, are forbidden to Christians. The ancient Israelites lived under a law that allowed engaged couples to cohabitate. Any children that resulted from such liaisons were considered legitimate. This practice was allowed, however, only because of the importance of procreation at that time. But for Christians, this law has been superseded. The rule against premarital sexual activity is much more strenuous for them than it had been for the Hebrews. Nothing, including offspring, is more important than “feminine honor.” It should never be surrendered prior to a legitimate and lawful wedding.

Although Luther vigorously condemned sexual relations before marriage, he reserved his most strenuous remarks for adultery. Interestingly, Luther saw adultery as a psychological and social, as well as a moral, evil. While God punishes those who are guilty of adultery, the vice is also its own punishment. Those who are guilty of it bring unhappiness to themselves and others. According to Luther, the “basis and complete essence of marriage” is the promise made to one’s spouse to remain faithful and forsake sexual relationships with all others. Anyone who breaks this promise severely damages this human relationship. As Paul had said in 1 Corinthians 7:4, the body of each spouse is exclusively the other’s. Luther told husbands and wives that they have a great obligation to each other and should ask for strength so they will be able to remember their duty. Adultery is worse than any theft, he said, for no restitution can be made to the injured spouse. Since it deals with life and honor, it takes what can never be given back. In a broader sense as well, one who commits adultery harms the community, for such a person violates the laws of reason and proper order. Luther therefore urged the community to punish and correct adulterers.

Luther’s perception of the evils inherent in sexual immorality is quite penetrating. It recognizes not only the violation of religious morality, but also the damage brought on individuals and society. His analysis of related issues is also often unusually perceptive for the time in which he lived. For example, he espoused no “double standard” of sexual morality. The breaking of marital vows is as serious a transgression for the husband as for the wife. Luther also does not espouse any notion of inherent feminine evil. While he believes that women should be subject to their husbands, he does not conclude that all women should be castigated. He urged men who criticized women to remember their own wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters.

Sexual Desire As God’S Gift

Luther also concluded that sexual desire is natural and, in the proper context, a positive good. He argues that sexual desire is of divine origin and that human sexual needs can be fulfilled in marriage. A man has a wife and a woman a husband to satisfy the innate yearnings of the flesh and to carry out the divine plan. Because God planted in spouses sexual love and desire for each other, sexual desire and sexual intercourse within marriage are natural and good. Indeed, part of the divine plan is for a husband and wife to love each other ardently. A comparison of this view with those expressed on the subject in the manuals for confessors of the late Middle Ages shows how far Luther had evolved.

Marriage is a great sanctifier. It makes good what would otherwise be evil. Luther shared the common belief of his time that God established marriage to help people avoid sexual sin. God calls men and women from all impure desires and acts. He established marriage as the divine institution that avoids, moderates, or sanctifies such otherwise evil lusts and desires. Since the fall of Adam, carnal desire has been mixed with evil lust, and marriage has been necessary to sanctify this passion.

Luther emphasized the positive nature of marriage as well. Marriage allows sexuality to realize its divine promise, not its satanic potential. He rejects the older notion that even in marriage sexual relations are more potentially dangerous than beneficent. While he did not approve of all possible extremes of sexual conduct in marriage, he dismisses it as a contradiction the idea that “anyone who is too passionate a lover with his own wife is himself an adulterer. “A man simply cannot commit adultery with his wife.

At the same time, the relationship between a husband and wife consists of more than just carnal desire. While one might not be able to commit adultery with one’s spouse, Luther warns against becoming consumed with “evil lust.” He accuses some Christians of being like the heathen, seeking and finding no more in marriage than brief carnal pleasure. He therefore carefully balances marriage as a means to avoid sin with what he believes to be the necessary physical expressions of love in marriage.

Luther Attacks Priestly Celibacy

Luther also rejects the exaltation of clerical celibacy. The adherents of Rome perverted the true order established by God when they set up celibacy as a higher state than matrimony. The false doctrine of the Roman church not only exalts those who are unmarried and celibate, but even worse, denigrates those who are married. For example, the papists termed the celibate religious orders “spiritual” and marriage “temporal.” In fact, marriage should be considered a spiritual condition and celibacy anything but that. Adam’s marriage predates any papal impositions and shows the standing of marriage according to God’s Word.

Procreation in marriage is a divine command with which people should not interfere. Anyone who forbids marriage contradicts God’s law and God himself. Luther told any cleric who was considering marriage to examine Genesis. He would conclude that a man and a woman “should and must” be joined together in order to fulfill God’s plan. Individuals must be free to choose whether they want to live a celibate or married life. No vows made contrary to God’s law should prevent a person from marrying. Even if he had made a thousand vows and even if a hundred thousand angels told him not to marry, what is any of that when placed against the Word of God?

Celibacy is also contrary to nature and denies the natural laws God established. Sexual desire is not only irresistible, in the proper place it is natural, God-given, and good. Those who demand celibacy are wrong in denying the sexual urge. They insist that “a man should not feel his masculine body, nor should a woman feel her feminine body.” But that is not only irrational, it is impossible. No one can deny a basic bodily function. The desires connected with a person’s gender are not a matter of free choice or decision, but are necessary and natural. Common sense, in fact, demonstrates to anyone that celibacy is contrary to natural laws. “A woman was not created to be a virgin, but to bear children …;” even the way that God had constructed the feminine form demonstrates this obvious fact. By prescribing celibacy as a higher order than sexual release in marriage, the Roman church had seriously erred, for it tried to improve on God’s pattern for proper human relations. Such error, because it denies God’s natural order, is akin to blasphemy.

Luther, of course, had to deal with some of Paul’s statements that seemed to argue for the virtues of the celibate life. He does not avoid this apparent challenge. He comments at length on the seventh chapter of 1 Corinthians. In an early work, “Ein Sermon von dem ehelichen Stand” of 1519, Luther granted that inasmuch as marriage is a means to avoid lust, celibacy is still preferable if one has God’s grace for it. If an individual can remain celibate and feel no lust, that condition is seemingly better than marriage.

Later, in commenting on Paul’s letter to the Corinthians, Luther argues that in fact very few people are called to celibacy. “One must have the heart for celibacy …,” he said. “Where there is one celibate person there are more than a hundred thousand inclined to marriage.” Although celibacy is good for those few genuinely called to it, those who force young people without such callings into the celibate life of the cloister are “terrible murderers of the soul.” When Paul stated that he wished that all could be as he was, “he desired that every man had the higher gift of celibacy …,” knowing that to be impossible. In fact, Luther charged, there were obviously many more women, for instance, in convents than could possibly have been called to celibacy.

Celibacy is not a sanctified way of life for most people. Luther argues from a practical perspective that there are two things wrong with celibacy. First, celibacy leads not to spirituality, but to vice, since so few have in fact been called to it. Second, those souls in the cloister are shut away from the hearing of God’s Word.

In understanding Luther’s revulsion at celibacy as a generator of vice, one must remember his abhorrence of sexual sin. He believes that with the exception of idolatry and unbelief God punishes no sin as severely as he does sexual misconduct. He demonstrated this punishment in his actions at the time of Noah and in his treatment of the city of Sodom. Thus Luther is particularly aghast at any institution that seemed virtually guaranteed to produce such evil. Luther concludes that the overwhelming majority of the clergy are unable to live the impossible vows that celibacy forces upon them. They consequently and inevitably slip into fornication and worse, and the laity are not properly taught by either precept or example. As celibacy corrupts priests, the laity often live in conditions of shocking sin. Luther relates that the common people often live the most promiscuous of lives. Some scoundrels (both male and female) move around, marry several times, and treat marriage as if they were gypsies. He knew of a small town in which there had been no less than 32 couples living together without the benefit of marriage. The contrast with evangelical faith was strong, for the gospel cured the problem.

The other obvious problem with celibacy in Luther’s eyes is that it prevents the cloistered members of religious orders from hearing the Word of God. For most people who try to live it, the celibate life is at best a prison. Speaking of Leonhard Koppe, who had released nine nuns (including Luther’s future wife, Katherine von Bora) from their cloister, Luther said that some might consider him a thief. On the contrary, he was “a blessed robber.” The monastic life leads to no good, but works to the detriment of those who attempt to live it. Life in the cloister blinds its inhabitants to the gospel, for nuns are unable to hear the divine Word.

An underlying problem with celibacy is that it is not a true vocation. Since one important test of the legitimacy of a vocation is the presence of God’s Word, celibacy fails miserably. Indeed, the Roman church completely perverts divine doctrine when it declares celibacy a true calling. Marriage, not celibacy (at least for the vast majority of people), is a true calling. The medieval church had taken Paul’s comments and changed their proper meaning. Celibacy, therefore, is not simply a false vocation, it is a grotesque perversion of the divine will.

Luther’S Vision Of The Godly Home

Luther’s disgust at the celibate phase of his life contrasts markedly with his comments about his married phase. The latter was established and nourished by God, a place for deep and profound human relationships. The former was a false vocation that kept its adherents from the Word and led only to vice and corruption.

Luther established marriage as a centerpiece of evangelical social organization in a remarkably brief time. The changes he introduced, however, altered permanently Western attitudes toward marriage. Even where celibacy is practiced today, marriage is not denigrated. Luther’s vision of the godly home is revered by most Christian faiths today. In his own life he had evolved from being a cloistered monk to a husband and father able to feel and appreciate those sentiments that have been ever since associated with marriage and family. His sorrow at his daughter’s death and his pointed and practical comments on married life are completely comprehensible today. We have not molded him in our image, however. Rather, our civilization has been shaped by the pattern of family life that he established.