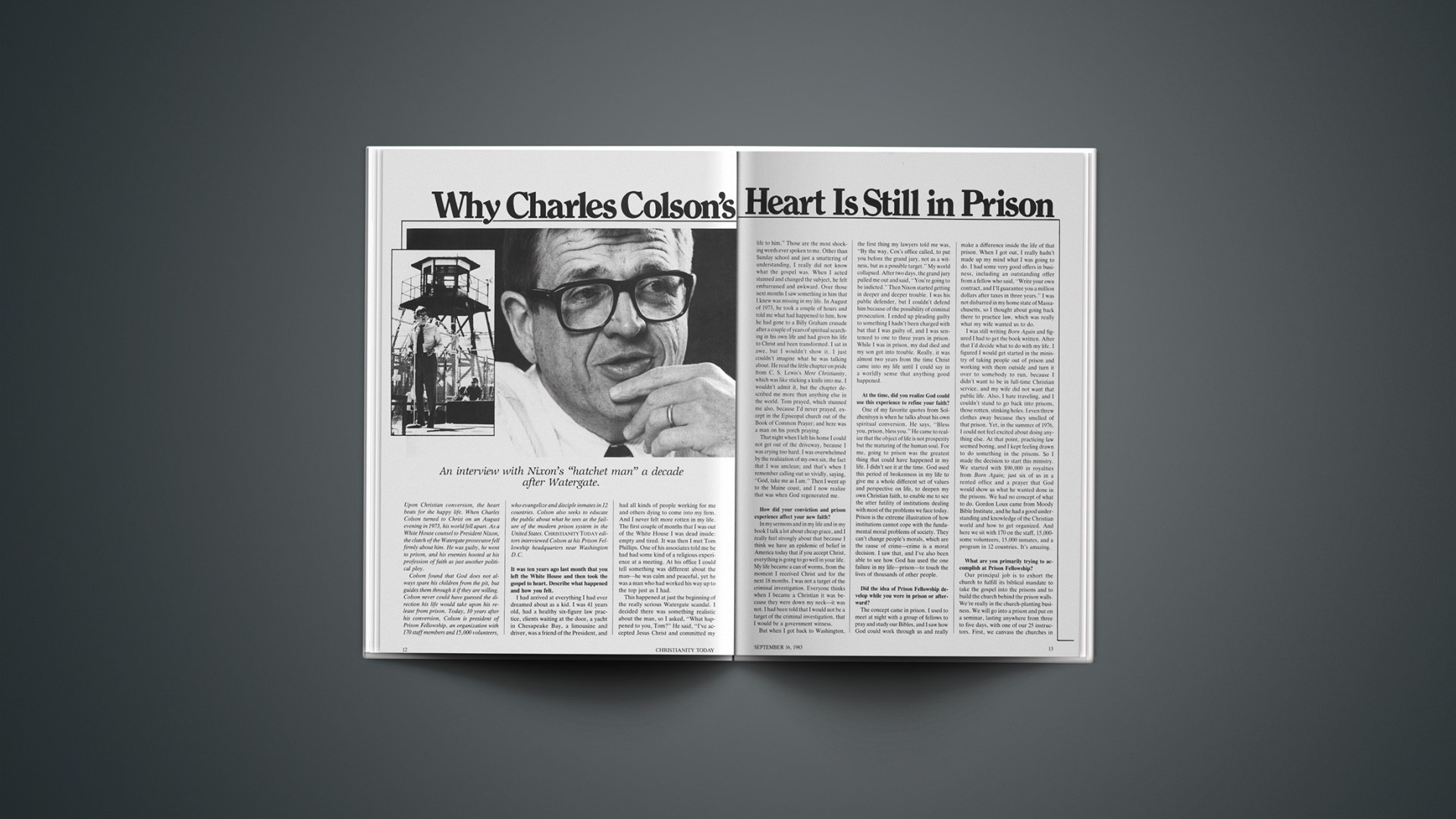

An interview with Nixon’s “hatchet man” a decade after Watergate.

Upon Christian conversion, the heart beats for the happy life. When Charles Colson turned to Christ on an August evening in 1973, his world fell apart. As a White House counsel to President Nixon, the clutch of the Watergate prosecutor fell firmly about him. He was guilty, he went to prison, and his enemies hooted at his profession of faith as just another political ploy.

Colson found that God does not always spare his children from the pit, but guides them through it if they are willing. Colson never could have guessed the direction his life would take upon his release from prison. Today, 10 years after his conversion, Colson is president of Prison Fellowship, an organization with 170 staff members and 15,000 volunteers, who evangelize and disciple inmates in 12 countries. Colson also seeks to educate the public about what he sees as the failure of the modern prison system in the United States.CHRISTIANITY TODAYeditors interviewed Colson at his Prison Fellowship headquarters near Washington D.C.

It was ten years ago last month that you left the White House and then took the gospel to heart. Describe what happened and how you felt.

I had arrived at everything I had ever dreamed about as a kid. I was 41 years old, had a healthy six-figure law practice, clients waiting at the door, a yacht in Chesapeake Bay, a limousine and driver, was a friend of the President, and had all kinds of people working for me and others dying to come into my firm. And I never felt more rotten in my life. The first couple of months that I was out of the White House I was dead inside: empty and tired. It was then I met Tom Phillips. One of his associates told me he had had some kind of a religious experience at a meeting. At his office I could tell something was different about the man—he was calm and peaceful, yet he was a man who had worked his way up to the top just as I had.

This happened at just the beginning of the really serious Watergate scandal. I decided there was something realistic about the man, so I asked, “What happened to you, Tom?” He said, “I’ve accepted Jesus Christ and committed my life to him.” Those are the most shocking words ever spoken to me. Other than Sunday school and just a smattering of understanding, I really did not know what the gospel was. When I acted stunned and changed the subject, he felt embarrassed and awkward. Over those next months I saw something in him that I knew was missing in my life. In August of 1973, he took a couple of hours and told me what had happened to him, how he had gone to a Billy Graham crusade after a couple of years of spiritual searching in his own life and had given his life to Christ and been transformed. I sat in awe, but I wouldn’t show it. I just couldn’t imagine what he was talking about. He read the little chapter on pride from C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, which was like sticking a knife into me. I wouldn’t admit it, but the chapter described me more than anything else in the world. Tom prayed, which stunned me also, because I’d never prayed, except in the Episcopal church out of the Book of Common Prayer; and here was a man on his porch praying.

That night when I left his home I could not get out of the driveway, because I was crying too hard. I was overwhelmed by the realization of my own sin, the fact that I was unclean; and that’s when I remember calling out so vividly, saying, “God, take me as I am.” Then I went up to the Maine coast, and I now realize that was when God regenerated me.

How did your conviction and prison experience affect your new faith?

In my sermons and in my life and in my book I talk a lot about cheap grace, and I really feel strongly about that because I think we have an epidemic of belief in America today that if you accept Christ, everything is going to go well in your life. My life became a can of worms, from the moment I received Christ and for the next 18 months. I was not a target of the criminal investigation. Everyone thinks when I became a Christian it was because they were down my neck—it was not. I had been told that I would not be a target of the criminal investigation, that I would be a government witness.

But when I got back to Washington, the first thing my lawyers told me was. “By the way, Cox’s office called, to put you before the grand jury, not as a witness, but as a possible target.” My world collapsed. After two days, the grand jury pulled me out and said, “You’re going to be indicted.” Then Nixon started getting in deeper and deeper trouble. I was his public defender, but I couldn’t defend him because of the possibility of criminal prosecution. I ended up pleading guilty to something I hadn’t been charged with but that I was guilty of, and I was sentenced to one to three years in prison. While I was in prison, my dad died and my son got into trouble. Really, it was almost two years from the time Christ came into my life until I could say in a worldly sense that anything good happened.

At the time, did you realize God could use this experience to refine your faith?

One of my favorite quotes from Solzhenitsyn is when he talks about his own spiritual conversion. He says, “Bless you, prison, bless you.” He came to realize that the object of life is not prosperity but the maturing of the human soul. For me, going to prison was the greatest thing that could have happened in my life. I didn’t see it at the time. God used this period of brokenness in my life to give me a whole different set of values and perspective on life, to deepen my own Christian faith, to enable me to see the utter futility of institutions dealing with most of the problems we face today. Prison is the extreme illustration of how institutions cannot cope with the fundamental moral problems of society. They can’t change people’s morals, which are the cause of crime—crime is a moral decision. I saw that, and I’ve also been able to see how God has used the one failure in my life—prison—to touch the lives of thousands of other people.

Did the idea of Prison Fellowship develop while you were in prison or afterward?

The concept came in prison. I used to meet at night with a group of fellows to pray and study our Bibles, and I saw how God could work through us and really make a difference inside the life of that prison. When I got out, I really hadn’t made up my mind what I was going to do. I had some very good offers in business, including an outstanding offer from a fellow who said, “Write your own contract, and I’ll guarantee you a million dollars after taxes in three years.” I was not disbarred in my home state of Massachusetts, so I thought about going back there to practice law, which was really what my wife wanted us to do.

I was still writing Born Again and figured I had to get the book written. After that I’d decide what to do with my life. I figured I would get started in the ministry of taking people out of prison and working with them outside and turn it over to somebody to run, because I didn’t want to be in full-time Christian service, and my wife did not want that public life. Also, I hate traveling, and I couldn’t stand to go back into prisons, those rotten, stinking holes. I even threw clothes away because they smelled of that prison. Yet, in the summer of 1976, I could not feel excited about doing anything else. At that point, practicing law seemed boring, and I kept feeling drawn to do something in the prisons. So I made the decision to start this ministry. We started with $90,000 in royalties from Born Again; just six of us in a rented office and a prayer that God would show us what he wanted done in the prisons. We had no concept of what to do. Gordon Loux came from Moody Bible Institute, and he had a good understanding and knowledge of the Christian world and how to get organized. And here we sit with 170 on the staff, 15,000-some volunteers, 15,000 inmates, and a program in 12 countries. It’s amazing.

What are you primarily trying to accomplish at Prison Fellowship?

Our principal job is to exhort the church to fulfill its biblical mandate to take the gospel into the prisons and to build the church behind the prison walls. We’re really in the church-planting business. We will go into a prison and put on a seminar, lasting anywhere from three to five days, with one of our 25 instructors. First, we canvass the churches in that local area and recruit volunteers to go in with us—mature Christians who can be core group leaders for the discussion groups; then we have a combination of lectures and discussions. Last year we held about 180 seminars. This year 240 are scheduled. That’s our principal way of reaching a lot of inmates. We also have a Bible study course in both English and Spanish, written just for inmates, that we use as a follow-up. We have a coordinated curriculum developed for all the instructors to use in prison seminars. We put on training conferences for church volunteers all over the United States. There are about 1,000 inmates whom we have taken out of prison for discipleship training. Finally, we take people out to work on community service projects. That’s one aspect of the ministry that excites me the most. Inmates are in groups of 6 to 12, and they spend two weeks living in volunteer homes, fixing up the homes of elderly people in the inner city.

Do you receive good support from churches?

Yes. One of the plusses of this ministry has been the enthusiastic response of the church by and large. There is a changing attitude in the church, which is much more receptive to this. A few years ago, if I talked about these kinds of things, you’d feel a chill go through a lot of churches. I think that’s part of the maturing process—a growing awareness maybe that government social programs aren’t really meeting needs, and that the church has a responsibility in this area. I think probably it is one real evidence I see of a spiritual awakening. Part of it is the resurgence of evangelicalism. I think evangelicals are more out front today than they were ten years ago, certainly more so than when I became a Christian. I had never heard of an evangelical.

Would you call your first book Born Again if you had it to do over?

No. I wouldn’t have if I had known enough, because I would have figured it was an overused cliché. I happen to be a Baptist and I go to a Baptist church. At the time I was still an Episcopalian. My wife is Roman Catholic, and I went to the Roman Catholic mass. She had picked up the people’s mass book and flipped it open to the page where the hymn “Born Again” was and said, “That’s what you should have called your book.” So I called the publisher and said I have a new title: “Born Again.”

He said. “Oh, no, that’s a tiresome cliché.”

I said it came out of the Catholic hymnal.

“Well,” he said, “It’s overdone with Baptists.”

I said, “I’m convinced it’s the right title, so you title it.”

What evidence have you seen to indicate that the prison system in this country is not working?

It’s self-evident that it isn’t working. We have the highest prison population per capita in the world except for the Soviet Union and South Africa. The prison population is growing 15 times faster than the general population and yet we have the highest crime rates. If prisons worked, we’d have less crime. FBI statistics show 74 percent of the people who get out of prison will be arrested again in four years. The whole system of punishment today is geared toward taking away people’s dignity, putting them in an institution, and locking them up in a cage. Prisons are overcrowded, understaffed, dirty places; 80 percent of American prisons are barbaric—not just brutal, but barbaric. A young man who is nonviolent, not really tough, and who’s under 25, is probably going to be homosexually raped the first month he’s in, in most American prisons and in the vast majority of American jails.

Half the people who commit crimes today commit nonviolent crimes, and they are the ones I’m talking about keeping out of institutions, as long as we’re able. If they’ve done shoplifting twice, we put them in prison for six months; shoplifting three times and they’re in prison for two years. We have just lost that guy, just turned him into a bank robber or somebody who is going to hold up the 7–11, or who’s going to rape or beat someone, because that will be the result of his prison experience. It is going to exacerbate whatever it is in that person that caused him to commit the crime in the first place.

I believe deeply in punishment, I believe an individual has to be held accountable, and I think he has to be confronted with his own sin. There’s no justice without punishment, but the punishment needs to be effective for the individual, and redemptive and beneficial to society. Prison as a punishment is a failure. As a place to lock up people and keep them off the streets, it’s a success. We need warehouses to quarantine dangerous people, but at most that’s only about half the people we incarcerate today. So we’re overcrowding and overloading the prisons, and the expense is absolutely staggering. The national average is $17,000 [per year to incarcerate someone], plus anywhere from $60,000 to $120,000 to build a new prison cell. And we continue adding people as we did last year, when 60,000 were added to the prison system. You are talking about $60,000 times 60,000—that’s just the capital expenditures—3.6 billion per year to keep even with the present prison population nationally. Most of that comes out of state budgets, which are already overtaxed.

What is the better way?

The biblical way. For property offenses, God has prescribed a system of restitution. Prison is a relatively new invention, really only about 200 years old, as a purpose of punishment. You’ll find throughout the Bible that prisons are there for political reasons or for people awaiting trial, but not for punishment. Biblically, we are told to make restitution. We have examples throughout the Old Testament, and Zacchaeus in the New Testament. I believe in alternatives to incarceration for nonviolent offenders.

What evidence have you seen of these alternatives being successful?

You really can rehabilitate someone when you let him see what he’s done—when crime is no longer an impersonal thing. If offenders have to work to try to make good to the victim, it makes it very personal. Second, when they start to make good, they feel good about themselves. When you throw someone who’s committed a crime in a cell, his selfesteem goes down, down, down. Everyone tells him he’s no good, and then when you put that person back out in the street, he believes he’s no good. But get him working to pay it back, and a sense of dignity returns—he really feels somebody cares about him.

The statistics almost universally show that restitution programs, community service programs, and counseling all have a rate of somewhere between 10 and 20 percent who return to crime, rather than the national 70 percent. Most of those figures, however, are misleading, because the people you deal with in those programs are handpicked and are motivated to make it. But everyone you put through one of these programs you can be pretty sure is saved from getting into that institutional jungle.

Are criminal justice officials open to the alternatives?

I can’t find anybody who’s disagreed with me yet. The whole question is public education. In covering the whole political spectrum, from far left to far right, everybody agrees. The whole issue is, Can we get the votes to do it? Do we dare say we ought not to be putting more people in prison? Politicans have played this tune so long, and it always gets applause. But how long does it take you to educate the public and get over that? Now, Florida is very significant. I felt like I was being thrown in the lion’s den when I had a meeting in Dade County, where crime is such a problem. I made the major proposal of the program, and I was afraid we’d get run out of that room—there were people standing up and shaking their fists at me. But the legislature went ahead and did it, and there was very little public uproar. I know they are definitely changing.

We had no idea of getting into the reform area in this ministry until I was in a prison where we later learned they were going to take me hostage. We didn’t know it at the time. One of the leaders was converted, and a riot was averted. We found out they were going to kill nine or ten guards, and we sat down and met with them and held off that riot. Then I was invited to address the state legislature on what was wrong with the prisons because they had heard what we were doing.

How do you feel about the death penalty?

I am very much opposed to it and always have been. I don’t want to give government that much power. It is too easy for an innocent man to be found guilty. Every single study on it shows that it really doesn’t deter crime or homicide. In two states, one right next to the other, one cut out the death penalty and the other continued it. In the state that continued it, homicides went up; in the state that cut it off, the homicides went down. If you study these crimes, 55 percent are among family members and close friends, and are crimes of passion. Crimes of passion aren’t deterred. A hired killer is not deterred, he just ups his price.

Everybody will read this and write in and say, What about Genesis 9:6—“Whoever sheds the blood of a man, by man shall his blood be shed.” I agree completely. But Deuteronomy 17 also says there must be two live witnesses before there can be an execution, and one of the accusers has to participate in the execution. And the reason for that standard was so they could be absolutely sure there would be no mistake. There is not one jurisdiction in the United States today that meets the standard that God has set. If we’re going to take God’s requirement that there be capital punishment, let’s also take his requirement to be sure we’ve got the right guy. Charlie Brooks died by lethal injection in the state of Texas with no one knowing whether he did kill that individual or not, and with the prosecutor pleading for clemency before he was executed—the prosecutor, because he didn’t know if he killed him. Charlie Brooks was not executed by biblical standards.

What prevents prison reform from taking place?

The biggest single obstacle to prison reform today is the lethargy of the public, the demagoguery of some politicians and the wholesale resistance of the conservative evangelical church to something that sounds liberal to them. My job is to explain to them that it really is biblical. That’s the amazing thing. Everything in our little booklet is out of the Bible, and when people read it they change; but we’ve got to educate them. The message has to get to them.

What could the average pastor do to help the public become more accepting?

I think since crime is the number two domestic problem, next to the economy in every poll, the concern is already there. Half of the American people say they are afraid to walk within one block of their homes at night, according to Gallup polls. When that happens, you’ve undermined the whole basis of biblical order in society, and the greatest danger is that people will sacrifice their freedom for order. If it’s a moral issue, as I believe it is, we ought to be addressing it by helping our children to understand their moral responsibilities at an early age and keeping that family unit together. Pastors ought to deal with the cause of crime and get people to realize that communities have to get involved. You cannot just take a guy and ship him off to the state pen and forget about him, because when he comes back, he’s going to be a real menace to your society. We have to deal with them in the community—send them down to the firehouse to paint it; make them go out and work among the poor in the streets.

Tell us about your latest writing project.

My next book will be published by Zondervan this fall, entitled Loving God, as the result of some very deep convictions about the need for the church to be equipped to defend the faith and then to have the courage to live it. As I look back on my ten years as a Christian, I’ve come to realize that not only is Christianity the way to live my life, not only is Christ real to me, not only am I sure of eternal life, but if Jesus Christ is really who I say I believe him to be, then that fact has to radically change everything about my life. That’s got to be the only thing that matters; nothing else matters. As I look around and see this enormous church, with buildings going up and people crowding in on Sunday mornings, it’s becoming a big entertainment circuit. People are going in just to be made to feel better on Sunday mornings. They are not approaching Christ as what he is—everything. So I’ve written the book with the hope it will challenge people to understand what they believe.

It’s very different from the other books, which are autobiographical. This is a book I hope will be very challenging for serious Christians who want to mature and really treat Christ the way I think he has to be treated if he’s what we believe he says he is.

Looking toward the future, are you committed to Prison Fellowship as far as you can see, or do you plan to turn it over to someone else?

Anybody who wants it! It’s one of the first jobs in my life I haven’t worried about losing. I wish my associates could take me out of the work; I have a little place down in Florida with a nice little fishing boat, and I love to fish. What drives me on is that I’m at perfect peace that this is what God has called me to do in my life. I have more peace about that today than I’ve ever had. I have no pride in the organization; I don’t want to build an organization. I want to be part of the movement of God’s spirit and see the whole church coming alive to what God has called the church to do and to be in our society. I don’t see any other hope. I will keep doing this as long as I believe it’s what God has called me to do, and as long as I’m able and needed and realize that so many people in prison need us.

My deeper feeling is about the need of the church of Jesus Christ to provide more leadership and vision in society, which is absolutely bankrupt without it. The values by which we live today are basically sick values. It is the church that provides the hope of moral leadership, which is why I have a deep longing to see the church be what God wants it to be, the invisible kingdom, to make its presence felt, and to be a witness. I think we’re looked upon too much today as just another institution, like any other agency of society. The church ought to be not just another organization, but the organism that is challenging society, giving leadership to society. The gospel has to be a disturbing message today, and it isn’t. It tends to be [presented as] just a religious adaptation of the false values of our secular culture.