Candid views from the popular evangelist who is at home in Latin America, Europe, and the U.S.

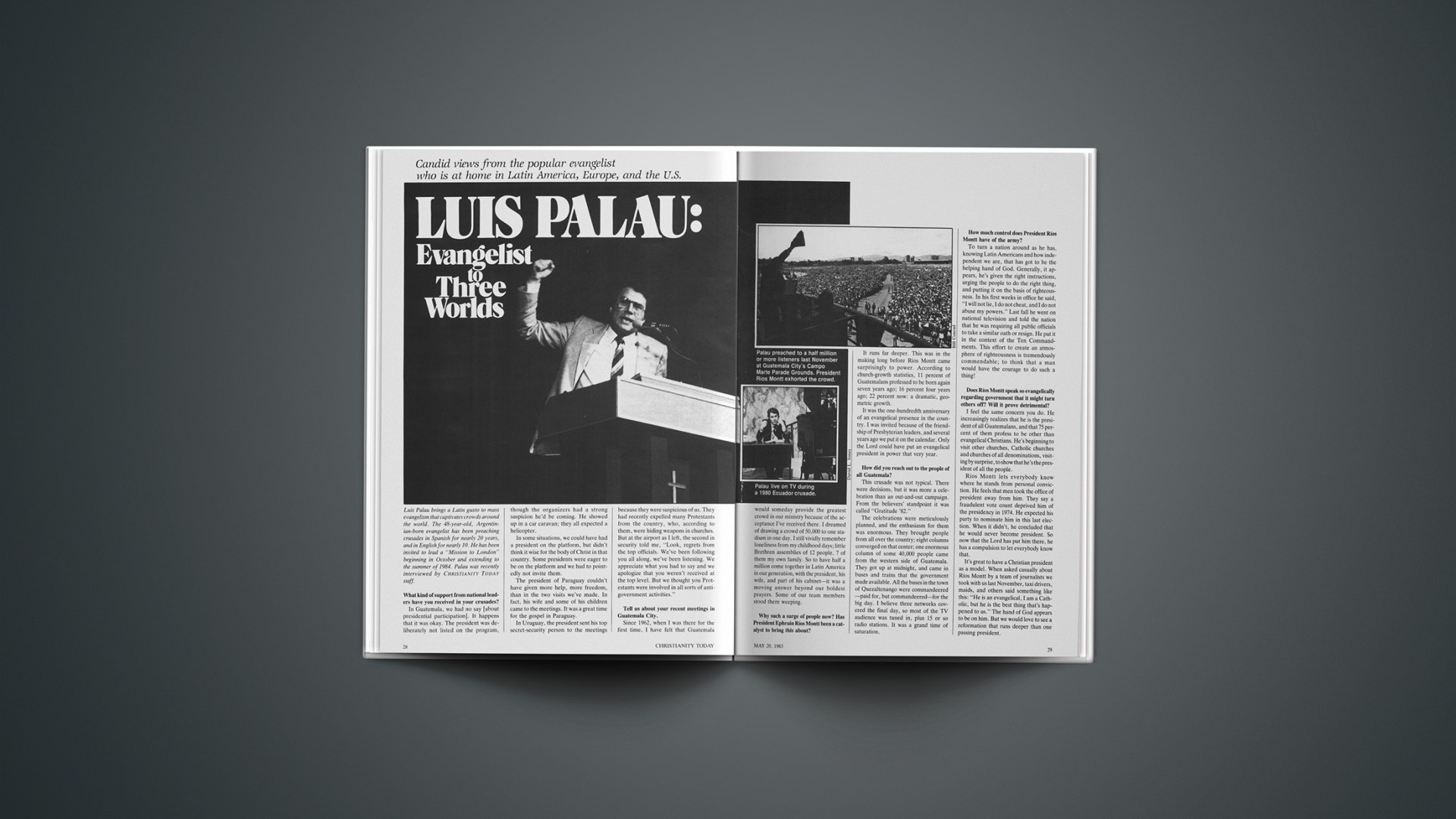

Luis Palau brings a Latin gusto to mass evangelism that captivates crowds around the world. The 48-year-old, Argentinian-born evangelist has been preaching crusades in Spanish for nearly 20 years, and in English for nearly 10. He has been invited to lead a “Mission to London” beginning in October and extending to the summer of 1984. Palau was recently interviewed by CHRISTIANITY TODAY staff.

What kind of support from national leaders have you received in your crusades?

In Guatemala, we had no say [about presidential participation]. It happens that it was okay. The president was deliberately not listed on the program, though the organizers had a strong suspicion he’d be coming. He showed up in a car caravan; they all expected a helicopter.

In some situations, we could have had a president on the platform, but didn’t think it wise for the body of Christ in that country. Some presidents were eager to be on the platform and we had to pointedly not invite them.

The president of Paraguay couldn’t have given more help, more freedom, than in the two visits we’ve made. In fact, his wife and some of his children came to the meetings. It was a great time for the gospel in Paraguay.

In Uruguay, the president sent his top secret-security person to the meetings because they were suspicious of us. They had recently expelled many Protestants from the country, who, according to them, were hiding weapons in churches. But at the airport as I left, the second in security told me, “Look, regrets from the top officials. We’ve been following you all along, we’ve been listening. We appreciate what you had to say and we apologize that you weren’t received at the top level. But we thought you Protestants were involved in all sorts of antigovernment activities.”

Tell us about your recent meetings in Guatemala City.

Since 1962, when I was there for the first time, I have felt that Guatemala would someday provide the greatest crowd in our ministry because of the acceptance I’ve received there. I dreamed of drawing a crowd of 50,000 to one stadium in one day. I still vividly remember loneliness from my childhood days; little Brethren assemblies of 12 people, 7 of them my own family. So to have half a million come together in Latin America in our generation, with the president, his wife, and part of his cabinet—it was a moving answer beyond our boldest prayers. Some of our team members stood there weeping.

Why such a surge of people now? Has President Ephrain Ríos Montt been a catalyst to bring this about?

It runs far deeper. This was in the making long before Ríos Montt came surprisingly to power. According to church-growth statistics, 11 percent of Guatemalans professed to be born again seven years ago; 16 percent four years ago; 22 percent now: a dramatic, geometric growth.

It was the one-hundredth anniversary of an evangelical presence in the country. I was invited because of the friendship of Presbyterian leaders, and several years ago we put it on the calendar. Only the Lord could have put an evangelical president in power that very year.

How did you reach out to the people of all Guatemala?

This crusade was not typical. There were decisions, but it was more a celebration than an out-and-out campaign. From the believers’ standpoint it was called “Gratitude ’82.”

The celebrations were meticulously planned, and the enthusiasm for them was enormous. They brought people from all over the country; eight columns converged on that center; one enormous column of some 40,000 people came from the western side of Guatemala. They got up at midnight, and came in buses and trains that the government made available. All the buses in the town of Quezaltenango were commandeered—paid for, but commandeered—for the big day. I believe three networks covered the final day, so most of the TV audience was tuned in, plus 15 or so radio stations. It was a grand time of saturation.

How much control does President Ríos Montt have of the army?

To turn a nation around as he has, knowing Latin Americans and how independent we are, that has got to be the helping hand of God. Generally, it appears, he’s given the right instructions, urging the people to do the right thing, and putting it on the basis of righteousness. In his first weeks in office he said, “I will not lie, I do not cheat, and I do not abuse my powers.” Last fall he went on national television and told the nation that he was requiring all public officials to take a similar oath or resign. He put it in the context of the Ten Commandments. This effort to create an atmosphere of righteousness is tremendously commendable; to think that a man would have the courage to do such a thing!

Does Ríos Montt speak so evangelically regarding government that it might turn others off? Will it prove detrimental?

I feel the same concern you do. He increasingly realizes that he is the president of all Guatemalans, and that 75 percent of them profess to be other than evangelical Christians. He’s beginning to visit other churches, Catholic churches and churches of all denominations, visiting by surprise, to show that he’s the president of all the people.

Ríos Montt lets everybody know where he stands from personal conviction. He feels that men took the office of president away from him. They say a fraudulent vote count deprived him of the presidency in 1974. He expected his party to nominate him in this last election. When it didn’t, he concluded that he would never become president. So now that the Lord has put him there, he has a compulsion to let everybody know that.

It’s great to have a Christian president as a model. When asked casually about Ríos Montt by a team of journalists we took with us last November, taxi drivers, maids, and others said something like this: “He is an evangelical, I am a Catholic, but he is the best thing that’s happened to us.” The hand of God appears to be on him. But we would love to see a reformation that runs deeper than one passing president.

Could you spell out what you mean by that?

I’m convinced of the truth of what George McGovern says, that change comes from the bottom up. You can exert influence from the top, but true change will come if and as masses are converted and change their lifestyles. The pressure forces the leaders to adjust to the masses rather than, as we often mistakenly think, the conversion of a president causes the whole country to follow.

There are many people in that nation with the education and the background to make Guatemala the first Reformed nation in Latin America. By a Reformed nation I mean one in which the gospel penetrates business, education, the military, and the government, and in which Christian ethics is the dominant force. That’s what I’m praying for: that the grassroots will live Christianly, that the nation will feel it, and that it will become a model for the continent.

How do you perceive the Roman Catholic hierarchy in Guatemala?

It appears to me to be quite broadminded. There’s a demonic rumor going around that there’s an evangelical-Catholic religious war going on in Guatemala. At my press conference, somebody asked me about that and I became incensed and turned on my Latinmost emotion for effect. The next day someone went and asked the auxiliary archbishop. The headlines appeared on the front pages the following day: “Archbishop says, ‘Ridiculous; there’s no religious war going on.’ ” I was pleased to see such a forceful, generous response.

Are you aware of the National Council of Churches report that associated Ríos Montt with massacres in the villages?

There’s no doubt that before Ríos Montt there was wanton killing going on; probably there is some still. I have a team of 48 people and I can’t control everything they do; I suppose if you are running a country of several million you can’t control everything. But I have read that even his political enemies say there’s a definite trend of respect for human rights that constitutes an absolute turnaround, and that his personal honesty is beyond reproach.

A journalist from our team, a Washington, D.C., correspondent, and a U.S. Senator’s aide asked the Guatemalan authorities if they could inspect three villages where there had been reports of atrocities. They heard conflicting accounts on the alleged massacres. However, in all three villages the government of Ríos Montt had successfully won back the confidence of the people through a program of rebuilding their villages, food distribution, establishment of schools and health care, and a unique civil defense program.

The feeling of those traveling with us to the crusade was that Ríos Montt was indeed trying to avoid civilian deaths and win back the population to the government’s side.

The World and National Council of Churches have their bias. I’ve seen it over the years in the statements they have made about Wycliffe Bible Translators, Billy Graham, and others.

What trend do you see throughout Latin America from an evangelical point of view?

I am encouraged by what I see. There is a small but disturbing percentage of liberation theology people among the evangelicals, and some who are even to their left. But generally speaking the body is maturing, there is continuing growth in terms of conversions, and an internationally minded leadership is developing that is stronger, more gifted, more mature, more respected by Latin Americans. Theologians are being developed in Latin America, some trained abroad but born on the continent, who can really think.

I think liberation theology is a menace in the sense that it creates a consciousness that we must do something about righteousness and poverty, but leads people in a disturbing direction. It’s held by a minority, but it can begin to have the effect of taking people away from the fundamentals.

What has been the source of liberation theology in Protestant circles?

Basically it’s been disseminated by the faculty and graduates of two seminaries. The Methodist seminary in Buenos Aires got into trouble with revolution, and the Latin American Biblical Seminary in San José, Costa Rica, taught it and spread it. The broad evangelical majority and pastors and denominational leaders do not go along.

What are the basic issues in the tug-of-war with liberation theology in Latin America?

The head-on collisions within evangelicalism and between evangelicalism and liberation theology are in three foundational areas: sin, redemption, and regeneration.

Basically liberation theology says that sin is in the institutions and in the structures. We grant that institutions need changing but ask if the essence of evil comes from the structures or from the people in them. We say that sin is from the heart of man.

Redemption, for the liberation theologian, is found in revolution: change the structures of the institutions and you will eliminate the sin that oppresses and you will have a free society. Whereas we say that redemption is spiritual; it was done on the cross; it comes by the work of Christ.

As for regeneration, basically, the idea of liberation theology is that the new man will emerge when institutions and structures are liberated from sin. We affirm that rebirth comes through Jesus Christ, and that individual, internal change will eventually change structures and institutions, bringing as much freedom and justice as a fallen world will allow. Your position on sin, therefore, strongly influences your position on revolution and change in a country.

If institutional change isn’t the answer for social ills, what is?

As I look at Scripture, church history, and the history of this century, I see no hope for institutional change that both lifts the masses out of poverty and maintains freedom. Suppose the economics of a Marxist system were superior. Would that be reason enough to justify such a revolution? Eliminating gross poverty at the expense of freedom is not a worthwhile tradeoff. I believe the change must come from the conversions of millions whose lifestyles then become Christian lifestyles; such a reformation and reconstruction is what will lift people up.

In some areas of Latin America up to 70 percent of the population is illegitimate. Those are United Nations statistics. If evangelical Christianity took hold, Christian families would multiply and a great respect for the family as an entity would develop. There are enough natural resources in Latin America so that these nations should not be in dire poverty. It isn’t the Sahara Desert!

If we could eliminate infidelity and immorality in Latin America we could cut poverty by half in one generation. Men earn a salary and they could manage financially if they practiced Christian prudence—even in Bolivia where a miner has to support a family on $100 a month. If a man gives up immorality with women, gives up getting drunk and all the waste (such as getting rolled over and having his money taken) that goes with it, and stops gambling, right there he is salvaging a big chunk of his salary.

In Latin America, of the millions that have been converted, until lately only a handful were middle or upper class when they were converted. The vast middle class now emerging was converted poor and rose through industry, honesty, and justice to the educated, reasonable lifestyle that is commonly called the middle class. I think that’s the biblical answer. When people charge that Christianity is a middle-class religion, I don’t see that as so damning. Do we want them still to be in misery?

Certainly some of the structures and institutions are repressive, but it is the lifestyle of the millions that will make the difference. Then Christians can penetrate the structures to be salt and light.

The only other options are unacceptable: the status quo or violent revolution, which does not lead to freedom for the gospel or dignity for the individual.

How should evangelicals be addressing the questions of poverty and oppression?

The beauty of the gospel is how the leadership, even without the background, can adapt by the grace of the Holy Spirit. We were not taught well enough, and we’re all catching up. I think what the vast majority needs to do is to truly switch—and we are switching—from the “stay out of politics; it’s absolutely dirty and impossible to touch” mentality we were brought up in, to one of “let’s get our young people involved in journalism, in politics, in the broadcasting media, in sports” and in all the influential circles considered completely worldly in the past. Everything was worldly except making a living and being faithful at church.

But as you begin to analyze these situations for yourself, you decide this is ridiculous. That isn’t even the way it is in North America. These missionaries come from countries where there are Christian, or at least Christian-influenced, people in government, and therefore they are enjoying the benefits of freedom. They just accepted what they picked up in Bible school, and they come down sincerely and say, “Just rejoice.” That may have been fair enough in the early days when any other response would have brought horrible persecution, but times have changed.

We must get involved, even at the risk of making mistakes and coming under attack. I think we are seeing some of that developing in Latin America, and that’s encouraging.

What needs to be done to give this trend a nudge?

One well-known theologian asked me, “What is needed in Latin America in terms of theology?”

And I answered, “Tell us how to biblically handle politics.”

He said, “Oh, leave me out of that.”

I said, “Look, in Central America the young fellows have to do theology for themselves on the run. They suddenly find themselves thrown into a revolution.” Sometimes it’s a conviction that dawns when someone is asked, “How about it?” with a gun to his head and to his sister’s head. He’s got to make a quick choice, and says, “It’s really wonderful; we believe in change.” Nobody prepared them to know how a Christian should operate when invited to join the military or the guerrillas. Suddenly they’ve got a theological problem, and a survival problem.

How do you view the situation in Nicaragua?

You hear both sides. We really need to pray, because it is easy to be confused and use biblical terminology, yet be an unconscious victim of the other oppression. After 50 years, the imperialism was so obvious. Fear is subtle in the moment of change. When you pray for people, think of the subtle pressures that nobody talks about, but that you can feel: If I make a wrong move, either I or my sister or daughter will bear the consequences. It’s terrifying.

I was raised in Argentina where if you wanted to survive you knew which subject just to ignore for the moment. You rationalized that God would bring about a change, and often he has. I have no easy answers.

Do you feel it is part of your role to be a prophetic voice to leadership?

I feel that the Lord has not called me to a public denunciation. I don’t see it as cowardice, either. I have spoken in private, with the Lord’s guidance as the opportunity arose, with several top leaders, including presidents. Take a verse such as Proverbs 11:26: “He that with-holdeth corn, the people shall curse him.” I’ve used that as a takeoff in private. I don’t think it’s the kind of thing you want to write a press release about.

I distinguish, as Ephesians 4 does, between an evangelist and a prophet. It is not my role to meddle in the prophetic. I recently spoke to a gathering of evangelists in England, and I made some off-the-cuff comments on the church and the bomb, while sitting with a writer. She interviewed me for an hour. The writeup zeroed in on three sentences—all of them correct, but taken out of context. So I came over as an extreme use-the-bomb type. The next time they ask me I’ll say, “Look, if you want to talk in private, I have a lot of opinions, just like my wife does, but my political opinions are not the views of the entire body of Christ.”

The World Council-sponsored CLAI [the Latin American Council of Churches] inauguration meetings held recently drew some Pentecostal involvement. What do you think this means for the future of the evangelically sponsored CONELA?

I believe in CONELA [the Confraternity of Evangelicals in Latin America]. To my mind it is the more broadly evangelical as I perceive evangelicalism to be, and the more representative of the true feelings of 99 percent of the evangelicals of Latin America. Some of them don’t know all the theological currents that go into these international events, the differences between CONELA and CLAI—particularly in the areas of liberation theology, strength or weakness in the view of Scripture, and the attitude toward out-and-out, good old evangelism. So without passing judgment, I would think that might be a reason why some Pentecostals participated.

The exciting thing about CONELA is what sharp, godly leadership the Lord has raised up in Latin America. I was impressed to see these absolutely Latin fellows hammering out doctrinal issues in committee meetings with true wisdom. CONELA is proving its maturity through the solid people who are leading it.

You have shored up CONELA in its beginning. Do you see that as part of your contribution to the church in Latin America?

Yes. I think a mass evangelist has the responsibility and privilege of encouraging those movements we as a team feel need a boost. At the call of many of the leaders, we intervened. They felt I would be a good catalyst, signaling to people that this is centered, balanced evangelicalism, that they can trust the theology behind CONELA. We were more than willing. And we also felt we should put in personnel and some support to help get the thing rolling. There are many people involved. I don’t want to take the credit; and more and more we’re going to fade into the background. But I am proud to have been there from the beginning, making this bit of a contribution to keeping evangelicalism on course.

How do you prepare for a crusade in Latin America?

We usually start 18 months ahead of time in order to embed the crusade deeply in the local church. We meet with ministers to bring spiritual cleansing and awakening within the leadership, to give church-growth vision and goals, and to try to set up church-growth plans along with crusade evangelism.

After the organizational structure begins to take place, we move in to bring awakening to the believers—at least a measure of cleansing and teaching on the indwelling Christ and the fullness of the Spirit among the Christians. Then comes the training period, then the mobilization. We keep before them the goal of reaching everyone, from the president to the humblest, poorest person in the country. We include an emphasis on evangelism of children and young people, trying to penetrate the whole spectrum of society.

Your series of meetings at the University of Wisconsin in Madison did not draw the response you get in Latin America. What does this tell you about American openness to the gospel?

It wasn’t disappointing in terms of the numbers professing Christ in relation to attendance. I was the invited guest speaker, not the organizer. The students who organized the meetings deliberately kept a low profile, which is not the way to touch a large university. Therefore attendance was lower than I would have wished. To get the attention of 40,000 students, you’ve got to make a lot of noise, really shake it up. Next time I think we’d be more involved in the publicity. But it doesn’t discourage me about the U.S. In fact, I would like to do more.

Do you see a difference of methodology in evangelism in Latin America and in North America?

Yes, there is a difference and I’m still trying to understand it more fully. I’ve been in the United States off and on now for over 23 years, but I spend most of each year traveling around the world and I’ve never focused my attention completely on the American situation. Now I am doing that more as invitations to speak in America and hold crusades continue to increase.

For the most part, my messages are pretty much the same no matter where I am preaching in the world. We add local anecdotes, but I don’t change my approach too much.

Methodologically, we try to adapt to the local culture. We’ve been in San Diego and Bellingham, Washington. We’re going to Modesto, California; and now Chicago and Dallas look like possibilities. I think what we are developing is this: In comparison to Latin America, we’ll stage more in-the-vicinity-of-the-city campaigns before we come to the big united effort. Touch the suburban areas, touch the inner-city neighborhoods in depth. This is what we’re doing in London: nine campaigns this fall, then one united campaign next summer in a football stadium.

What challenge do you have for the church?

My burden now—besides the Latin area, which is always on my heart—is twofold: for America and Europe.

In America I see a transition. The generation that took us out of World War II and the liberal-fundamentalist debate has written one of the greatest chapters in the history of the church. It delivered evangelicals from a strident, anti-intellectual image. It went for a two-pronged approach with both intellectualism and activism, bringing evangelicalism into God-honoring prominence and respectability in the proper sense. Its leadership outdistanced the liberal camp that appeared so overwhelming to our fathers.

But now that generation is beginning to go on to glory. It is handing over the baton to the next generation and saying, “What are you going to do with what we, by God’s grace, did?” And that’s where we need to resolve, “By his grace, we’ll pick up from there, keep it going, and if possible, better it in areas.”

My challenge to the States would be: Let’s not be an accepting, passive generation. The tendency is for the first generation to be vibrant and active, and for the second to become passive. We hardly realize what happened to us. We’re having a great time; we’ve got all these publications, radio programs, youth movements, campaigns. The third generation degenerates theologically and ethically, going all the way back to questioning the fundamentals; and practically giving up on evangelism, church growth, and solid theology.

I see myself in the middle, as one of those picking up the baton. And I discern a trend toward fragmentation in the U.S. So how can we evangelicals maintain the sense of unity, respect, and support for one another that our fathers and grandfathers passed on to us? We’ve got to pick that up, enhance it, and not allow fragmentation to set in.

What are your goals for your service to the church?

Pray that the Lord will lead us. I feel we’re going to have campaigns in the States; invitations are coming from big cities like Chicago, Dallas, and Birmingham, Alabama. We want to be used of God for effective, God-honoring, large crusades, which I think help to preserve that evangelical unity.

In England, there seems to be a fire brewing under the surface among the young people and now within the leadership. Six or seven years ago when I went there for the first time, they cited 4 percent attendance in church; now, last year, there is 11 percent adult church attendance. Church attendance is not the greatest barometer, but it does speak of something. The campaigns coming up for us in London and for Dr. [Billy] Graham, in the five other major cities of Liverpool, Bristol, Birmingham, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and Norwich, could bring a new awakening to England. Because I was converted through British missionaries and went to British boarding schools, I dream of being used of the Lord to bring blessing back there, to pay my debt, so to speak. I would ask for prayer for revival in the British Isles as much as in the United States.